Select Other Languages French.

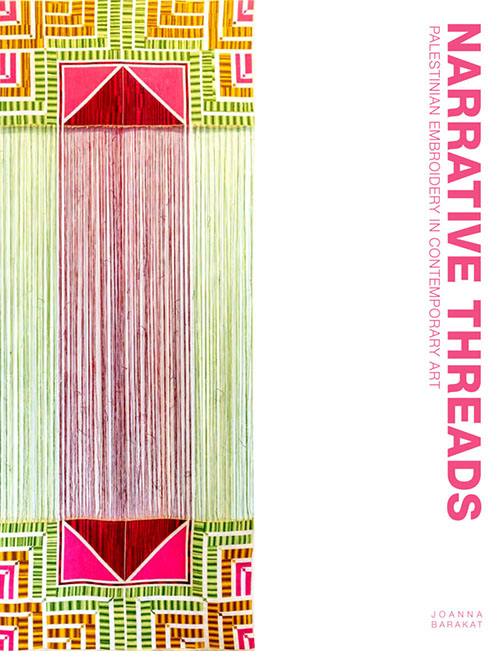

In the past, tatreez — a traditional, handmade artform produced on clothing by villagers, farmers, and Bedouin women — once acted as localized memoir reflecting personal experience and place. Now, in the hands of artists and Palestinians at home and in the diaspora, tatreez is part of a powerful cultural movement that expresses Palestinian identity, cultural resilience, and homeland. Joanna Barakat reveals the story of how she came to write her new book, Narrative Threads: Palestinian Embroidery in Contemporary Art.

I smiled through the knots in my stomach and the restless tapping of my feet as the group piled onto the tour bus, chatting about sites they had visited and souvenirs they had bought.

My phone rang again.

“Where are you? They’ve been waiting for over three hours now. Sliman wants to leave. Have you reached Ramallah yet?”

I didn’t know how to tell Ziad, Nabil Anani’s son, who arranged my meeting with Sliman Mansour and Nabil Anani, that I was still on a tour bus outside the Old City of Jerusalem, waiting for the rest of our group to arrive. We were around 20 friends and family, who had travelled from Los Angeles and Korea and everywhere in between. They were excited to tour Palestine that summer of 2019.

I was there for a different reason.

“Please tell him to wait. I’m on my way.” I said, feeling terrible that I had kept them waiting. I certainly didn’t want legends of the Palestinian art world, men of my father’s generation, to think that I didn’t respect their time. The bus doors finally closed, and we headed toward Ramallah.

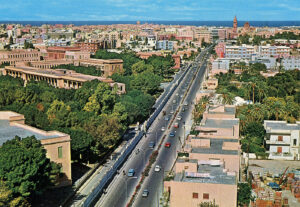

From Jerusalem to Ramallah

I nagged the bus driver to go faster. He told me to relax and sit down as we approached the military checkpoint. We handed a variety of foreign passports up to my uncle, our tour guide, who added his and the bus driver’s Palestinian ID cards. He passed the pile to the armed Israeli soldier who boarded the bus to inspect the hodgepodge of passengers. I prayed that we’d get through the checkpoint quickly. Depending on the soldier’s mood, we could be there waiting five minutes or five hours. I reminded myself that our tour bus, with its designated license plate, afforded us privileges that Palestinians living under Israeli occupation and apartheid in the West Bank didn’t have. It’s unlikely that we would be held at checkpoints for hours to be humiliated and abused, as Palestinians are daily. Our bus can travel on Jewish-only roads and enter areas only designated for Jews. Even Palestinians who hold Israeli citizenship are also limited in their rights and movement.

The soldier returned the passports quickly, and we were on our way.

The tour bus finally pulled up to Nabil Anani‘s house, where he and Sliman Mansour were sitting outside at a small table by the side entrance of his home and art studio. Though they seemed amused by my unusual ride, the mood was still heavy. Anani offered me a seat, and then coffee was served with a homemade date-filled kaak pastry. I apologized for making them wait, and when I noticed Mansour stood up, prepared to leave, I immediately cut to the chase — I had come to discuss the potential of a book on Palestinian embroidery in art. Mansour’s rigid posture loosened, and he sat back down as Anani filled his pipe with tobacco. I explained how researchers and journalists often reached out to me to ask about Palestinian embroidery in art, and how people knew little about the impact that artists like themselves had in creating the symbolic imagery associated with Palestinian embroidery.

An indigenous language

Their eyes brightened as the conversation began around the subject that tied us together. I showed them a photo of my painting Heart Strings (2017), a visceral self-portrait where I depict myself stitching a Palestinian embroidery motif onto my chest. This was the first artwork I had created where I stitched directly on painted canvas. For this piece, I asked my sister-in-law, Ghada, a talented embroiderer, to teach me how to cross stitch. I was mesmerized by the way she brought colors and patterns together with a needle and thread.

I began researching the history of Palestinian embroidery, or as it is commonly referred to in Arabic, tatreez. When searching for more motifs, I came across the book Guide to the Art of Palestinian Embroidery (1984) written by Anani and Mansour. Each of the embroidery motifs they documented in this book had a specific meaning, or bore a resemblance to something familiar. I was intrigued by how Palestinian embroidery could be interpreted as a form of Indigenous language. This discovery unlocked a way for me to relate to my Palestinian culture and heritage through my artwork. After years of my broken Arabic making me feel like a foreigner in my own skin, I was finally able to express myself in a language that was uniquely Palestinian.

An archive of stitches

As we discussed their book, Anani and Mansour shared stories from their time researching Palestinian embroidery motifs. They had been especially interested in elderly women who could tell them about the older motifs and their origins. Historically, it was the villager, farmer, and Bedouin woman who wore the traditional embroidered dress. The motifs embroidered on a woman’s dress spoke to what village she was from, the elements of her natural environment, her beliefs, her economic and marital status, and even personal information she may have wanted to share. Women would come together to stitch and share stories. In these spaces, girls would learn important life lessons, such as the birds and the bees, while listening to the neighborhood drama from the older women in their family. The stories told through motifs on dresses, as well as the oral history shared in their creation, form an archive of Palestinian women’s cultural narrative over centuries. Even dresses with decorative embroidery, or those worn only for special occasions, carry with them moments in time, embodying a Palestinian woman’s story as she lives it.

From Jerusalem to Tel Aviv

Reflecting on Palestinian elders and their stories reminded me of the first time I met my husband’s paternal aunts during our zaffe, the Palestinian wedding procession. In their hand-embroidered dresses, they swung their hips and waved their arms to the celebratory rhythm. They lent the scene the authenticity I had always craved. The line of men hired to lead the zaffe, dressed in the traditional qumbaz and kuffiyyeh, clapped and sang traditional wedding songs. Our families clapped and ululated along to the drums that beat as fast as our hearts. Our friends and families encircled us as we took one step in front of the other together.

No one in my family wore embroidered dresses, yet I felt a strong sense of affinity and connection to them. Embroidery became an essential part of my life through my husband and his family. It went from being a random sighting to an art form that colored my walls, wardrobe, and time.

Both of my grandmothers preferred western fashion and subscribed to the common notion that only rural women wore traditional embroidered dresses. Soon after my father was born in Khalil in 1949, Zionists made his family refugees, and they moved to the Old City of Jerusalem. My grandmother on my mom’s side, Teta Khadija, was born in Jerusalem and displaced to Karak, Jordan, during the British Mandate Period. She moved back to Jerusalem after getting married and was again displaced to Karak during the Nakba in 1948. My mother was born and raised in Karak, then moved to Jerusalem after she married my father. He started his antiquities business in the Old City and expanded to Bethlehem before we immigrated to Beverly Hills when I was a toddler. My mom ran her household outside of Palestine just as her mother had before her, where the moment you stepped inside our house, she filled your senses with the sounds, smells, and tastes of Jerusalem.

The only embroidery that came with us was a couple of cushions that my mother’s sister had stitched, and two antique pillows from Khalil, stashed away in my mother’s closet. My mother once said, “Your father brought us from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv,” describing how Zionism was profoundly embedded in the fabric of the city of Beverly Hills and in its residents. I grew up in an ignorant and racist community programmed to hate Palestinians, Arabs, and Muslims. This is the reason so much of my art aims to inform, and to invite humanity back to the conversation. It is also why the little stitches on those cushions called to me.

Souk economics

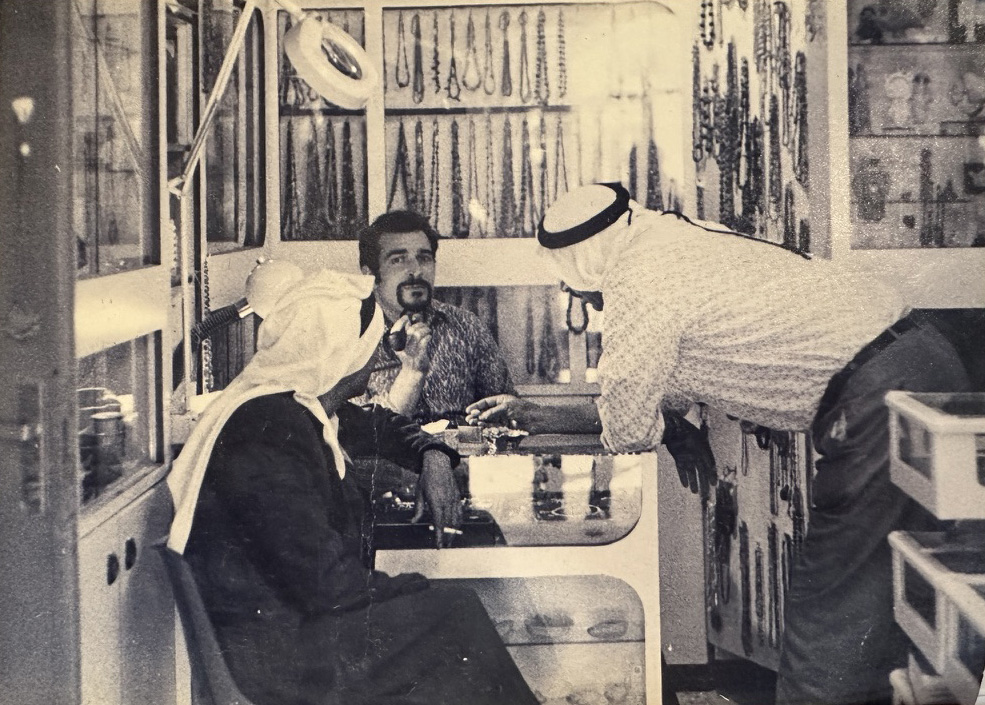

Before heading to Ramallah, the morning of my meeting with Anani and Mansour, my father and I had walked through the Old City. He had pointed to the brightly colored embroidered dresses sold in the small shops that lined the narrow streets. “They used to sell these dresses for $5 in the 1970s,” he said. I imagined how desperate a woman would have to be to sell her precious dress for so little after carefully laboring over it for months, and how dresses had been stolen and left behind when Palestinians were forced out of their homes by Zionists. I thought of the American and European tourists who bought these dresses as Holy Land souvenirs without any understanding of their cultural importance or the ancestral knowledge that went into their making. The historic Palestinian hand-embroidered dress, a personal, bespoke expression of a localized identity, changed in form and meaning after the Nakba of 1948. About a decade later, motifs and regional styles merged into a new hand-embroidered dress style that sprouted from refugee camps. This style coincided with the rise of the commodification of Palestinian embroidery, where women began selling their hand embroidery to tourists and foreign markets through organizations and social enterprises to create an income for themselves. The hand-embroidered dress, once a rural item of clothing, evolved into a luxury that many women could no longer afford.

While looking at the dresses hanging from the windows or stored in tall piles in the little shops of the Old City, I considered how the cost of these dresses has changed based on their perceived value and market demand. Throughout the centuries, Palestinian dress mirrored and responded to the economic and cultural conditions of the time. Like my grandmothers, women who lived in Palestinian cities preferred western-style clothing, which they considered a modern and sophisticated way to dress as opposed to the rural embroidered dress, or thobe. During Ottoman rule, there were times when women were known to reduce the amount of embroidery on their dresses to avoid higher taxes, since more embroidery was seen as a display of wealth. Under the British Mandate period, women sewed up the front openings of their dresses to protect their modesty from the gaze of British colonial soldiers. Following the devastation and displacement caused by the Nakba and Zionist occupation, a new dress style emerged from the camps, followed by the widespread adoption of the affordable and easily produced machine-embroidered dress. From the 1980s onwards, machine embroidery and mass-produced machine embroidered dresses on synthetic fabrics made wearing embroidery affordable and accessible. Though this sort of dress had its advantages, it removed the inherent value and sustainability of the hand-embroidered dresses. Cotton, linen, and silk fabrics were replaced with polyester, and machine-embroidered dresses could now be bought in shops. This was a stark contrast to the cherished hand-embroidered, handmade dresses for personal use, which were mended, cared for, and passed down as heirlooms to the next generation.

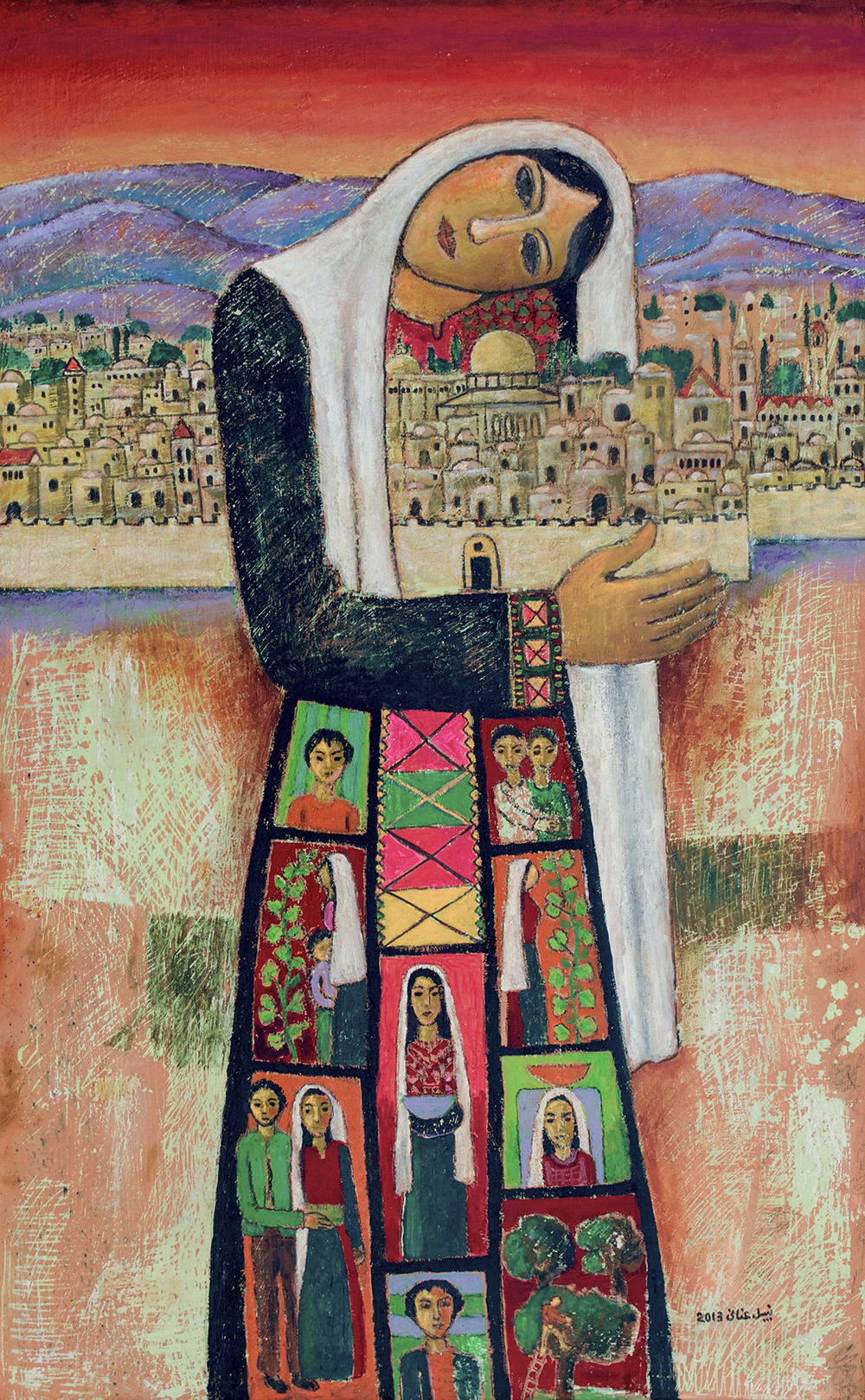

Artists reframe Palestinian embroidery

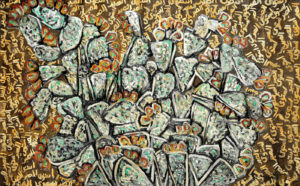

In the mid to late 1960s and 1970s, Palestinian artists such as Anani and Mansour and their contemporaries sought to create art that sparked a sense of national consciousness. To do this without having their art confiscated by Israeli soldiers or being arrested for something as silly as using the colors of the Palestinian flag, they created a visual language which communicated ideas about Palestinian liberation, steadfastness and identity using symbols that resonated with a Palestinian audience. A painting or drawing of an olive tree or a woman in her embroidered dress spoke volumes about the Palestinian people’s attachment to and intimate relationship with their homeland. This imagery illustrated the nostalgic stories of a Palestine before the catastrophic and traumatic loss it endured. The Palestinian woman in her embroidered dress became a metaphor of Palestine, the motherland.

Posters of paintings, prints and drawings depicting this imagery were distributed throughout refugee camps in Palestine and the diaspora. The symbolism transformed attitudes around the embroidered dress; something that was once considered traditional rural attire became a celebrated symbol of collective identity and was worn with great pride, regardless of the wearer’s social strata. Women wear embroidered dresses to events, celebrations and weddings. Like the embroidered Intifada dresses, embroidered dresses are still worn to protests as an embodiment of Palestinian culture and identity.

Preservation, resistance and community

I shared with Anani and Mansour how I had started teaching tatreez workshops in 2018, after receiving a phone call from my friend, Dina Yazbak. She was concerned that Palestinian embroidery would be a remnant of the past, and that her daughter’s generation would know nothing about it by the time they grew up. I explained the importance of learning its history, as the context provides the valuable meaning needed to understand why it is so much more than just decorative embellishment. Dina graciously offered to host my first workshop at her house for her and her friends. Since that first tatreez workshop, the presentation has evolved and improved, but kept the same format, where I teach how to cross stitch after providing a detailed overview of the history of Palestinian embroidery and presenting contemporary artists who incorporate tatreez in their work. This is when I started The Tatreez Circle on Instagram to share my passion for Palestinian embroidery with others who were interested. Palestinian embroidery has seen a great revival since then. At that time, I could count the people I knew teaching Palestinian embroidery workshops on one hand. Now, it is hard to keep up with all the workshops and “tatreez circles” held all over the world. Social media, YouTube, and online resources have made it possible to access embroidery motifs, tutorials, workshops, and businesses worldwide.

Anani and Mansour emphasized the necessity and urgency of preserving our embroidery, stressing that it should continue to be documented, along with other forms of cultural heritage. Since 1948, Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from their native land includes attempts to erase Palestinian culture through violence, theft, and appropriation. Like many forms of Palestinian cultural heritage, Palestinian embroidery serves as evidence of Palestinian indigeneity and existence.

Since the beginning of Israel’s devastating genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, there has been a rise in interest in Palestinian embroidery, with artists and embroiderers using tatreez to express, better understand, or get closer to their Palestinian identity. Their artwork featuring embroidery is shared on social media, embroidery is worn and displayed in protests, and people worldwide are coming together to stitch in community. We can now find in-person and online communities built around the practice of embroidery, creating space for connection, healing, solidarity, and allyship. Teaching and sharing Palestinian embroidery are ways to celebrate and form a meaningful connection to Palestinian culture.

Many people are now stitching and sewing their own embroidered dresses by hand. Here, they are reclaiming the ancestral practice, bringing back its indigenous and sustainable features. They are engaging in an act of self-care and healing. This is also an act of resistance against the colonial violence and extreme capitalism that aims to erase cultural and indigenous practices.

Palestinian embroidery is dynamic, and artists, designers, and makers are constantly finding new ways to innovate and reinterpret it. As more people take up tatreez, create content about it, and teach its history, I noticed there is a missing conversation about how artists have crafted and sustained its symbolism associated with Palestinian identity.

Narrative Threads: Palestinian Embroidery in Contemporary Art

I was thrilled that Anani and Mansour, two renowned Palestinian artists, educators, and art advocates, who shaped our imaginings of Palestine, were enthusiastic about being featured in my book. It was essential for me to include artists who had taken part in the creation of the symbolism that has transformed how we understand and relate to Palestinian embroidery.

This first meeting led to five years of research, interviews, and meetings with many more artists who carried Palestinian embroidery forward and reimagined it across all mediums. Ensuring that each artist’s voice is prominent in their chapters with first-hand quotes about the role Palestinian embroidery plays in their artwork, limited my curation to only include living artists I could interview. Palestinian embroidery needed to be part of their art practice or feature prominently in their work. I also looked for work that included Palestinian embroidery stitched in the artwork, imagery of embroidery, or even practices and ideas heavily influenced by embroidery. The inclusion of the three essays gives the book additional context for the reader and offers a valuable resource to anyone researching the subject.

Just as the dresses documented and responded to the lives and times of their wearers, artwork that incorporates the imagery and motifs of Palestinian embroidery taps into the varied personal experiences and ideas of the artists. Artists explore concepts and challenge notions, inviting us to think about the world we live in.

It may be that the conquerors and the colonizers write the history textbooks and control the mainstream media, but it is the artists and makers who shape the culture that captures the soul and stories of the people. I used to think our insatiable homesickness drove us to fetishizing and romanticizing a Palestine of the past, where the movement of a needle and thread through fabric alone could transport us to a Palestine before the extreme horrors and violence of Zionism. While the feeling is real and shared amongst many Palestinians, I now know that it is the artists who painted the picture that colors our minds, fills our hearts, and forges our connection to Palestine when we see an aunt in her hand-embroidered dress dancing in front of us.

After thanking Anani and Mansour for their time and hospitality, I waved goodbye as I opened the taxi door. I smiled all the way to the restaurant in Ramallah, where I joined the rest of the group. My smile was a promise to deliver a book that honors the artists who have shaped, and continue to shape, the meaning of Palestinian embroidery in our collective consciousness.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)