Select Other Languages French.

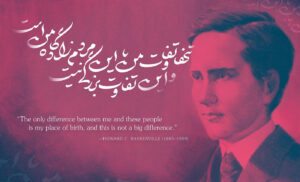

It’s nearly impossible to save face and rebuild national identity, especially after losing a war. Iran attempts to woo a weary populace with exhibitions, billboards, even promises that past transgressions, like fleeing the country after the 1979 revolution, can be forgotten and forgiven.

Following the end of the 12-Day War, new developments have emerged in Iran’s cultural and urban landscape. On the surface, they may seem scattered, but together they appear to be part of a broader strategy aimed at boosting public morale and repairing the government’s image among its citizens. From the renewed prominence of nationalist symbols in public spaces to the display of artworks once banned or marginalized in museums — even inviting expatriate cultural practitioners back home — these moves signal fresh efforts on the part of the regime to revive hope in a society still reeling from the anxiety of the war with Israel less than three months ago.

One striking example is the installation of a statue and mural of Arash the Archer in northern Tehran’s Vanak Square. In Persian mythology, Arash (whose name means bright or luminescent in Farsi) fires an arrow. Historically where it fell defined the country’s borders. The 15-meter bronze statue, by Mohammad Dehghan Mohammadi, the son of renowned Iranian sculptor Iraj Mohammadi, has an imposing backdrop nearby. An unmissable mural, covering most of a building that looms over a bus station and taxi rank, shows missiles launched alongside Arash’s timeless arrow. This pointedly curated public space suggests that both military prowess and ancient myth now share the duty of guarding Iranian borders that are crucial to the country’s identity.

In the same climate, a YouTube interview between pre-revolution pop star Shahram Shabpareh, based in the US, and the popular talk show host Ali Zia sparked widespread reaction. Shabpareh’s comments about the hardships of life in America, such as high insurance costs and social insecurity, prompted mixed responses online. Critics accused him of “ignoring the realities of migration.” They also took exception to him talking with Zia, a presenter formerly affiliated with state media. In a later interview, Shabpareh reiterated his affection for the Pahlavi royal family and his disdain for the government that forced him into exile.

Meanwhile, at home, newly elected president Masoud Pezeshkian has spoken of creating conditions for the return of Iranians abroad. Despite the arrest of returnees in the past, Pezeshkian urged the judiciary and the intelligent services to coordinate between each other to allow those who were homesick for Iran back into the country after some 47 years in exile. These signals from the government, combined with cultural projects such as major museum exhibitions, are part of concerted attempts to offer both a semblance of historical continuity and psychological stability to a domestic public that has not only been wounded by the war but shaken by the arrests of some of their neighbors mistakenly identified by the regime as collaborators with Israel.

Women’s art but not their hair at TMOCA

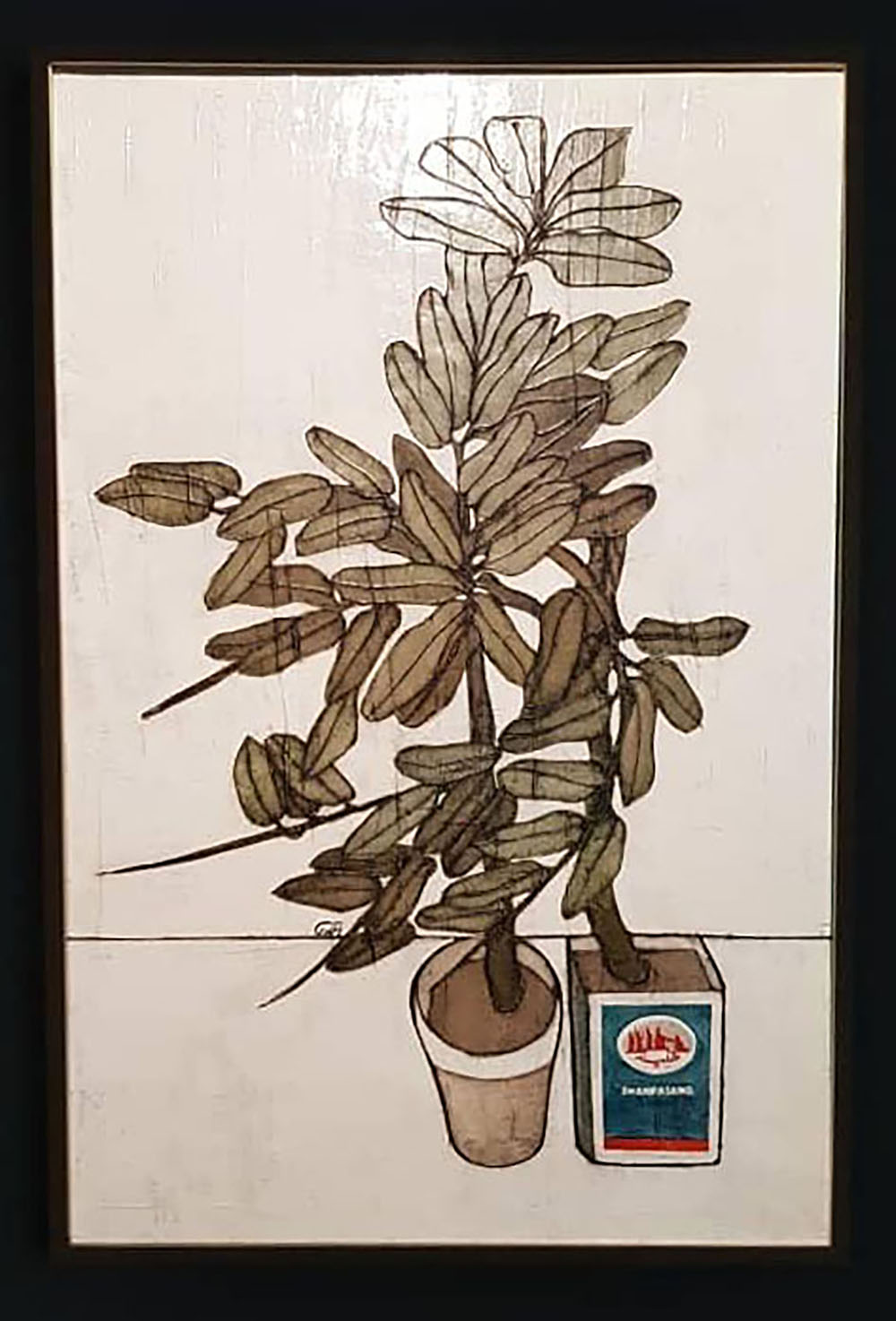

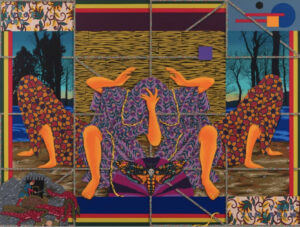

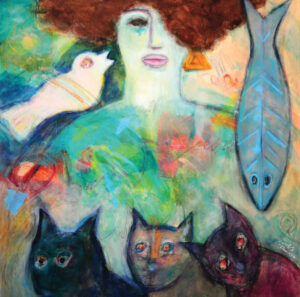

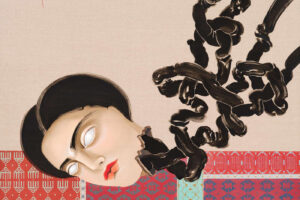

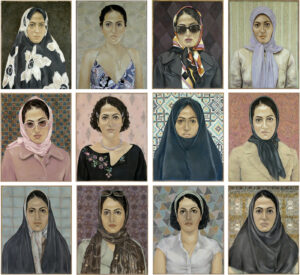

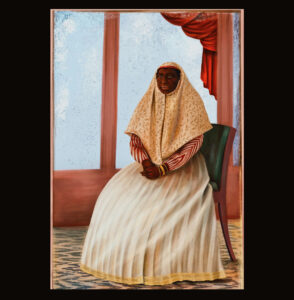

One of the most high-profile cultural efforts of recent weeks has been the exhibition, In Women’s Words, at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA). On until September 22, it features works by pioneering Iranian women artists from the years preceding the 1979 Iranian Revolution. According to the brochure accompanying the exhibition, “The diversity of works by modern Iranian women in the two decades of the 1960s and 1970s recalls an era of freedom, experimentation, and boldness, marked by pluralism and the dominance of modernism.”

On view is artwork by Behjat Sadr (1924–2009), Parvaneh Etemadi (1948–2005), Mansoureh Hosseini (1926–2012), and Farah Ossouli, all prominent Iranian women artists whose art younger Iranians rarely have had the chance to see. Many visitors to the TMOCA expressed delight at encountering these pioneering works for the first time. The exhibition, curated by Toka Maleki, Afsaneh Kamran, and Sajad Baghban Maher, under the supervision of Reza Dabiri Nejad, brings together paintings, photographs, sculptures, and video art by Iranian women — some of whom had been sidelined due to the political or critical stance of their work.

On opening day, I went with a friend who wasn’t wearing a headscarf. I told her they might not let her in. She shrugged: “If there’s a problem, I’ll just throw my shirt over my head.”

At the museum entrance, two women security guards in chadors told women showing hair that they need to wear a covering. Most complied with a scarf or a piece of clothing, only to remove it once they were inside. This small but telling scene captured the daily dual between officialdom and public behavior. It is a gap that many navigate in the country’s bifurcated social psyche.

Among the works on display were video pieces “Turbulent” and “Tooba” by the artist in exile Shirin Neshat. Neshat had left Iran in 1974 to study art in California and returned briefly to visit the country in 1990. In “Turbulent” (1998), traditional male singer Shoja Azari sings a Persian love song to a packed auditorium on one side of a spilt screen. On the other, the experimental singer and composer Sussan Deyhim in a scarf improvises, her voice echoing around the empty seats of another auditorium. In “Tooba” (2002), a woman disappears into a tree as men approach. In her art, Neshat has been known for her sharp rebukes of Iranian gender politics and power structures.

The threat of war and impending economic doom have drained peoples’ confidence, focus, and motivation. Iranian society remains caught in a state of uncertainty, exhaustion, and psychological fracture. In such conditions, rushed cultural projects may serve more as a temporary sedative than a path toward lasting renewal.

Also included in the exhibition were a series of photographs by Yalda Moaieri, arrested in 2022 for covering the Mahsa Amini protests. She spent several months in prison, and adding insult to injury she was made to clean the streets. Remarkably, not only were her photographs shown at the TMOCA exhibition, this artist who had left Iran for the US but found it wanting, had returned back again. She was now out on bail.

Another artist included In Women’s Words was Zohreh Kazemi — better known as Zahra Rahnavard, artist, writer, politician, and wife of Mir Hossein Mousavi. Rahnavard, currently out on conditional release, had been under house arrest with her husband since the contested 2009 elections. Although she recently gave a public dressing down of Netanyahu for Israel’s targeting of women and girls during the onslaught on Gaza, she has long been a formidable critic of Iranian state policies. Her inclusion in the exhibition is a notable symbol of either a change in tone or at the very least a rethinking by official institutions on how to reconfigure the cultural space.

According to museum organizers, all these works have been part of the TMOCA’s collection for years. At the opening some artists admitted to me they were unaware of when the museum purchased their pieces — or whether they had ever received payment for their work. One of the curators reportedly told a participating artist, “We have no intention of excluding anyone,” but when asked about restrictions imposed from outside the curatorial team, i.e. the government, the curator had no answer.

I learned from some artists I spoke to at the opening that they had been contacted only a week before the exhibition’s opening and had been asked to send in a work if one was available. Another artist with art in the museum’s permanent collection said that only after she had received an invitation for the opening that she realized she had been included in the show. Given that exhibitions of this scale usually require months of planning and coordination, the hurried nature of this event was notable. It seems In Women’s Words was intended as a much-needed cultural response — a way to help restore a sense of normalcy after the shock of war.

Urban billboards

Historically, large-scale imagery in public space has been one of the mainstays of government communication with the Iranian people. During the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), artists like Khosrow Hassanzadeh (1963–2023) painted the faces of martyrs killed during the war and these became both symbols and celebrations of the ultimate sacrifice these men and boys gave to the country. Their plaintive expressions stared down from buildings throughout the capital. For many, the war represents a time when only a year after Ayatollah Khomeini came to power, the country was on the same footing: under attack, it had been able to mobilize thousands of volunteer citizens to the cause of protecting the nascent Islamic regime. While martyr murals from that war have not entirely disappeared from the urban landscape, a new iteration has sudden appeared. Cutouts of group shots of fighters from the 1980s, as evidenced by the clothes they are wearing, have been affixed to the sides of bridges. Some stare pensively at passersby, while others appear almost jolly.

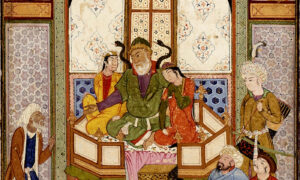

The government is keen to emphasize the connection between the politics of today and Persia’s distant past. In a billboard that went viral in July, instead of the Roman Emperor Valerian on his knees in humiliation and defeat before a Sasanian king, Netanyahu appeared in bowed supplication to King of Kings Shapur I (240–270) in a mock rock relief modeled on the one from Naqsh-e-Rostam, near Persepolis, the ancient capital of the Achaemenid Empire.

Political billboards quickly change. Now in a square, a billboard foregrounds military commanders and nuclear scientists killed in the 12-Day War against a backdrop of monarchs, including Cyrus the Great (600–530 BC), from different Persian dynasties. All appear under the slogan: “We are the guardians of Iran in every era” — linking contemporary figures with historical defenders of the land. Interestingly, the billboard represents a sudden shift in the Islamic Republic’s traditional use of historic narrative. For decades, the government distanced itself from the monarchy, emphasizing its break with past dynasties, particularly that of Mohammad Reza Shah and his 2,500-year celebration of the monarchy as a continuous legacy, which took place in Persepolis. Yet, after the 12-Day War, the regime facing social instability at home appears to be relying on Iran’s royal history, connecting present-day military and scientific heroes with monarchs of the past. The result is a surprising and unusual pairing of two historically opposed narratives.

Another banner appearing over a highway in Tehran features a fighter clutching a map of Iran to his chest, with the words: “Did you know, if Damascus falls, Tehran could be next.” Erected for 18 Mordad in the Iranian calendar (August 8 in the Georgian), it is a symbolic day of remembrance for “Holy Shrine Defenders,” or martyrs and veterans who defended sacred places. In effect the government was providing an answer to its critics who had the temerity to ask during the 12-Day War: why the country was so heavily invested in regional militias and wars, like Hamas and Gaza, when its own people and economy were suffering.

Many artists believe the public mood is not yet ready for a genuine return to work and creativity. The threat of war and impending economic doom have drained peoples’ confidence, focus, and motivation. Iranian society remains caught in a state of uncertainty, exhaustion, and psychological fracture. In such conditions, rushed cultural projects may serve more as a temporary sedative than a path toward lasting renewal.