Daniele Rugo’s documentary film The Soil and the Sea pieces together the events of Lebanon’s devastating civil war, which forced a million people out of the country, and ruminates on the myriad dead who lie in unmarked mass graves.

Farah-Silvana Kanaan

“Even if it’s just a bone, we want them, just to honor them and bury them.”

You’ll never be able to look at the sea, or anywhere else in Lebanon, the same way after watching The Soil and the Sea (Lebanon/UK, 73min. 2023), a documentary that ruminates on unmarked Lebanese Civil War-era (1975-1990) mass graves. Through voice-over testimonials by missing persons’ desperate loved ones, you learn about what has eluded them for decades: closure. An understated, and therefore even more powerful, reminder of the darkest pages of the country’s turbulent history, the film masterfully weaves together past and present without a trace of sentimentality or cinematic manipulation. The Soil and the Sea should be part of the collective Lebanese consciousness — and part of the curriculum at Lebanese schools.

Directed by Daniele Rugo, who also produced the film with Carmen Hassoun Abou Jaoude, The Soil and the Sea pieces together Lebanon’s devastating civil war — which forced nearly a million people to flee the country in order to avoid the fate of almost 120,000 of their slain compatriots. This is achieved through intimate recollections by the loved ones of some of the war’s estimated 17,000 missing people — kidnapped by this militia or that army — with the camera alternating between showing us deceptively common contemporary scenes and wartime footage. The film exemplifies the adage “less is more,” offering the only voices that matter in such a scenario — those of the victims.

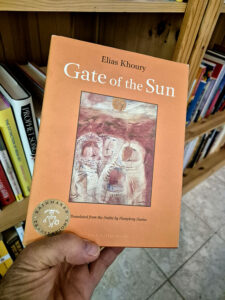

In fact, there is no beginning-to-end narrator soothing the viewer with unbiased facts in a trustworthy tone, as is often the case in traditional documentaries. Notably, however, Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury narrates the film’s poetic prologue. Levantine Arabic is spoken throughout, while excellent English subtitles ensure that nuances are not lost on a foreign audience.

Lebanon is a country where the ruling class has perpetually tried to force collective amnesia upon its people. But in that same country, where every attempt at change is stymied, the act of remembering plays a crucial role in enabling people to survive the indignities to which they were and continue to be subjected. Whether through poetry and literature or film and archives, or even a simple conversation, every shared memory is ammunition. It is the only thing ordinary citizens have left to combat the warlords — most of them still in power, albeit as politicians.

Its name is the White Sea. This is how we call it in our language. We sit on its endless shore, tell it our stories, and listen to its stories. It melts our sorrows in its blue white and it paints the horizon of our relationship with the sky.

This introductory voice-over is by Khoury; he wrote the lyrical yet sobering soliloquy especially for the film. It is filled with melancholy yet tinged with simmering anger. That’s an emotional state that is far from alien to the Lebanese, even, or especially, today.

Bridging the atrocities of the Lebanese Civil War with the now near-daily reports of refugees drowned in the Mediterranean, Khoury points to the perpetual fate of this sea as a mass grave. It has become, in his words, “a vast, boundless cemetery” that “opened its guts, like a mythical beast swallowing corpses.”

It’s not just the sea that has swallowed corpses. “I wish there was a law that enabled us to dig around detention centers, because there are mass graves,” one Lebanese woman laments.

Why would Lebanon prevent the passing of such laws? One answer comes towards the end of the film, from a man who narrowly escaped death during the Damour massacre in 1976. After the war, he asked the president of his local municipal council for help in unearthing a suspected mass grave near his house. Help was promised, yet never came — a common occurence in Lebanon. However, rather than challenging the authorities and risking harm being done to him or others, he relented. “Those who committed the massacre are still out there,” he notes.

And, he continues:

How are you going to be able to exhume graves without losing anyone because of it? I don’t want to lose more people because of the exhumation of graves. What would I do if I had to choose between forgetting and saving another family from losing someone? I would save someone. The human life is important.

At times, the film feels like a haunted historical tour of Lebanon. A woman who was a high school student in the early stages of the war used to walk from Achrafieh to Furn al-Chebbak at night. “I could hear my heartbeat,” she recalls, as she was “afraid to step on a body.”

Oftentimes, while a person is recounting his or her experiences, we’re confronted with the very locations where they took place. The camera lingers on them just long enough to elicit discomfort on the part of the viewer. If you’ve lived in Lebanon or even just visited, you start to remember when you walked past these sites, ashamed that you didn’t know about them, or, if you did know, that you didn’t spare a thought for those buried underneath.

Even those of the missing who ultimately resurfaced were not spared the torture of trauma. One man recalls that, when he was released, his mother didn’t recognize him. Recounting this soul-crushing moment 30 years later, he chokes up. “Where is Fawaz?” his mother asked, even as he stood before her.

The many parallels with what’s occurring in the region today are impossible to ignore. When a woman recalls seeing her husband for the last time before he and others were executed by the Israeli army, which invaded Lebanon in 1982, it conjures up images of all the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza whom the Israeli military continues to kill with impunity. The fact that it doesn’t matter on which day you read or hear about the incident is telling.

Another woman describes going all the way to Syria, which took part in the war, to look for her missing brother, only to be confronted with a big sign at the entrance of Tadmur prison: “Those who come in are missing and those who come out are reborn.” How can you not think of the Syrians who are languishing away there now, their families sick with worry and unable to get on with their lives?

When she made her way to Syria, the woman recalls, “the young men in Tadmur prison were constantly screaming, ‘Oh, mother!’ ” Their voices could be heard outside. As it happens, this woman’s mother ended up losing her mind. She refused to put up any pictures of her son in the house, insiting that the only “real” picture of him was the one she carried around her neck. And she seemingly talked to herself — only for her daughter to realize that she was talking to her missing son.

While the testimonials juxtaposed with contemporary footage of alleged locations of unmarked mass graves have the required unsettling impact, there’s a lot of information here for the viewer to digest, oftentimes with little context provided. Even as a Lebanese who is intimately acquainted with the protean civil war, which raged for 15 years, I found myself confused at times. For the uninitiated, the alliances and rivalries, the political and social circumstances, the perpetrators and victims, all of which changed frequently, may well prove a bit much. Additionally, the translation can sometimes be confusing for those unaware of the context.

Ultimately, however, the The Soil and the Sea is powerful, and its power lies mostly in its details: recollections of limes being thrown at bloated, decaying, and dismembered bodies stacked atop other bodies after the Sabra and Shatila massacre; a donkey carrying a stretcher laden with piles of burnt bodies; a burnt dog tied to a date tree; a mother walking under the jets — “a red fire going up in the sky” — to deliver newly bought clothes and chocolate bars to her son, a ninth-grader fighting in the ranks of a militia. He disappeared before she could give them to him. Remembering such horrors when you’re supposed to forget them is a revolutionary act.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)