Select Other Languages French.

A new monograph offers a glimpse into the acclaimed architect's motivations and upbringing.

Provoking the Territory: Bernard Khoury, by MK Harb

Dongola Architecture Series 3

Dongola 2025

A new book reveals how Lebanon’s “bad boy architect” has been indelibly shaped by Beirut. Written by MK Harb* and edited by Raafat Majzoub, Provoking the Territory: Bernard Khoury is textured with the architect’s archives and direct quotes. The book is presented in a familiar and conversational style. It is also unexpected, refusing the steady cadence common to the monograph. Instead, Harb moves forwards and backwards through the architect’s lifetime to linger on and return to particular projects, the better to offer a multidirectional trajectory of Bernard Khoury’s personal and professional development.

Bad Boy Architecture

Widely associated with his architecture of the entertainment industry in post-war Beirut, Bernard Khoury began his career with the 1998 war bunker nightclub B018. The project attracted significant controversy, as it occupied the site of a former massacre. In Provoking the Territory, Khoury argues B018 labeled him a “media architect.” Yet, Harb reveals how B018 was deeply personal to Bernard Khoury. The name of the nightclub refers to a unit number at Al Manar Seaside Resort at Maameltein, designed by his father, architect Khalil Khoury, in 1982. The book’s use of archival materials and consultation of Khoury lend credence to its nuanced interpretation of an architect widely considered as insensitive. For example, drawings of Al Manar Seaside Resort at Maameltein, from the Khalil Khoury archives, anchor Bernard Khoury’s insistence on the genius of his father’s designs and, in turn, give weight to the book’s provocation that B018, and perhaps the architect’s practice at large, was highly deliberate.

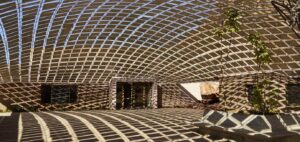

Home to the vinyl record collection that belonged to Bernard Khoury’s cousin, “B018” was the unit where the younger male members of the Khoury clan spent their formative years. Weaving interviews with Khoury throughout, Harb also reveals how the nightclub’s material and mechanization was situated in the specific craft and construction knowledge of its industrial neighborhood. The design of B018 — subterranean, concrete, and with a retractable roof — was made possible only through the architect’s familiarity with material ranging from wood and chemicals to concrete and mechanized metal work, honed from his childhood working in the family’s furniture industry.

Provoking the Territory thus subverts readers’ expectations of the architect’s monograph, drawing on oral interviews and archival documents to reveal how an architect defined by private commissions might also have formatively shaped a city. As “an alternative memorial” that bridged wartime and postwar Beirut, B018 was a nightclub, but it was also a temporary imposition in the subterranean strata of Beirut. As effective as any public commission, B018 served as an architectural reminder to a public emerging from wartime that forgetting the past has been and can be as vital as remembrance.

Unsettling readers’ presumptions about Bernard Khoury, the book also uncovers little-known practices and projects of the architect. His “Evolving Scars” project, produced while Khoury was a student of Lebbeus Woods at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) at Harvard University, is revealed to have greatly influenced his understanding of the architect as, above all else, a “thinker.” For this performance piece captured on 35mm film, Khoury built a concrete model encased in glass to document its demolition, a commentary on memory and the (im)material. The extent to which “Evolving Scars” has informed the evolving approach of the provocative architect is not fully divulged at once. In the book, as in his Khoury’s life, the influence of this specific piece is revealed episodically, in conversations on different projects throughout the architect’s career. For example, Harb recalls how Khoury was confronted with the need to demolish the Grande Brasserie du Levant. His choice to preserve the footprint of the former brewery while demolishing its original structure invokes his framing of destruction and reconstruction as relational, explored in “Evolving Scars.” The book similarly juxtaposes the project from Khoury’s time at the GSD with its discussion of his decision to leave scars on the facades of the high-end residential towers he was tasked to rehabilitate in the wake of the August 4, 2020 port explosion. The scars serve as a memorial, destruction, and reconstruction, again, offered as inextricable.

For an architect whose reach extends well beyond the built environment, the book engages with the architect’s published and unpublished writing as part of his architectural practice. Bernard Khoury is the author of Local Heroes (2014) — an account of the architect’s professional career that explores a cast of characters who surround him; it centers the process of negotiation that scaffolds this web of relations between contractors and architects, politicians and clients. Meanwhile, Khoury’s unpublished architectural fiction Toxic Grounds departs from the autobiographical to see the territory as real estate; a chapter of the book entitled “The Forgotten History” was included in a volume on modern architecture renovation in the Global South, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism, co-edited by Raafat Majzoub with Nicolas Fayed. In interviewing Bernard Khoury on Toxic Grounds, the book moves beyond the scope of the traditional architectural monograph to invite readers into the broader ecosystem of publishing in the region, in which the Dongola Architecture Series plays a prominent role.

The Dongola Series

Provoking the Territory is the third installment in the Dongola Architecture Series (DAS) edited by Raafat Majzoub, following Critical Encounters: Nasser Rabbat and Notes on Formation: Ammar Khammash. Each interrogates the architect’s biography, pulling threads across the multimodal works of leading architects in the region, using their projects, reflections, and career trajectories to speak to broader socio-political contexts.

In situating its analysis in the formation of individual architects rather than an architectural survey, the Dongola Architecture Series sidesteps some of the pitfalls of writing on architecture in the region. It acknowledges the influence of history, but like its publishing house Dongola, is firmly contemporary. It neither excavates the traditions of the past for a solution to the present nor does it assert an architecture of techno-utopian futurity. Vernacular architecture is acknowledged in the ways in which it mediates the environment and climate. However, the series doesn’t fetishize the local, nor renounce outside influence on its architects and their process. The rarity with which one encounters a monograph of an architect framed by their experience, rather than a broader argument of what the architecture of the region — whether preoccupied with the cultural, religious, or environmental — is perhaps indicative of a broader shift in writing on architecture of this territory. It is a welcome one, with Provoking the Territory a conspicuous example.

* The Markaz Review has published several short stories by MK Harb.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)