Events deprogrammed, works withdrawn from sale, awards postponed — since October 7, a number of creatives have dealt with a wave of reticence or cancellations on the part of European and American institutions.

Nada Ghosn

On October 16, after the deadly Hamas attack on Israeli territory, Palestinian author Adania Shibli received a brief email from the Frankfurt Book Fair, informing her that the presentation of her prize had been postponed, and that her meeting with the public had been cancelled. The German association LiProm, which was to present her with the LiBeraturpreis for authors from the Global South, summarily justified the decision by citing “the war between Hamas and Israel” that had been raging for 10 days, and the desire to make Israeli voices “particularly audible.”

A few days later in New York, the 92nd Street Y, a venerable Jewish institution, canceled a scheduled reading by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen without explanation, just a day after he signed an open letter condemning Israel’s “indiscriminate violence” against Palestinians in Gaza, according to Reuters. Nguyen wrote on Instagram, “Their language was ‘postponement,’ but no reason was given, no other date was offered, and I was never asked. So, in effect, cancellation. Some people in social media comments say they heard it was a bomb threat. I’ve heard no such thing from 92Y staff.”

The 92Y didn’t stop with cancelling Nguyen alone; a few days later, the organization put its prestigious literary series on hold after several writers withdrew from events to protest its decision not to hold Nguyen’s reading, according to the New York Times. 92Y disagreed with Nguyen’s anti-war stance, but the novelist wasn’t alone. More than 750 artists signed an open letter in the London Review of Books calling for an immediate cease-fire, charging that Israel’s “unprecedented and indiscriminate violence” in Gaza constituted “grave crimes against humanity.”

At the Frankfurt Book Fair, Adania Shibli was to be honored for her third novel, A Minor Detail. Twelve years in the writing, this slim novel deals with the rape and murder of a young Bedouin woman by Israeli soldiers in 1949. In a press release, the author denies the statements made by the LiProm association in which they claimed that the decision was made in agreement with her, and asserts that this choice was an imposition.

Shibli’s cancellation provoked strong reactions in the literary world. More than 600 personalities signed an open letter published in Le Monde, protesting against the decision, including Nobel Prize winners Abdulrazak Gurnah, Annie Ernaux and Olga Tokarczuk, as well as Canadian writer Naomi Klein. “The Frankfurt Book Fair has a responsibility to create spaces for Palestinian writers to share their thoughts, feelings and reflections on literature in these cruel times,” the letter reads. Several Arab publishing houses and literary agencies in turn declared that they were boycotting Frankfurt.

It wasn’t the first time that a European cultural institution altered its programming as a result of armed conflict between Hamas and Israel. A few days after the October 7 attack, the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris announced the cancellation of several events around its exhibition Ce que la Palestine apporte au monde / What Palestine Brings to the World (since extended until December 31).

Censorship

“The fear of importing conflict leads to censorship. But it’s not by censoring people that we build an enlightened discourse,” criticizes Rose-Marie Ferré, art historian and teacher-researcher at La Sorbonne, in an interview with The Markaz Review. “You have to welcome artists even if you don’t agree with them. They have the right to express themselves in a dialectical discourse. That’s how knowledge is built.”

After its cancellation in October following a decision by the mayor of Choisy-Le-Roi, the play And Here I Am, written by British-Iraqi playwright Hassan Abdulrazzak, was rescheduled for December; its cancellation was denounced by its French translator, Jumana Al-Yasiri, on her Facebook page. Based on a true story, the play follows the journey of Ahmed Tobasi, a young Palestinian born in the Jenin camp on the West Bank. From armed struggle to theatre as a tool of resistance, from the West Bank to exile in Norway, the show also recounts Tobasi’s meeting with actor and director Juliano Mer-Khamis, founder of the Freedom Theater in Jenin, who was assassinated in April 2011 by an unknown assailant.

Increased Visibility

Since 9/11, artists from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region have become increasingly visible on the international scene. Contemporary art centers have begun to open departments dedicated to the gathering of works from this region. One example is the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, which founded the Société des amis du MENA three years ago. A major exhibition of works by MENA artists is scheduled for April 2024 at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris.

“But efforts remain timid in Europe, and are largely due to private entities such as the Kamel Lazaar Foundation in Tunisia,” explains Laure d’Hauteville, director of MENA Art Fair, in an interview with The Markaz Review. In Brussels, where the market is particularly active, even though Belgium has no colonial past with the region, the Palais des Beaux-Arts (Bozar) opened a department specifically dedicated to art from the MENA region five years ago. The Wiels Contemporary Art Center also organized a major exhibition on the work of Lebanese artist Huguette Caland a year ago in Brussels.

“It takes moments of conflict for people to hear about what’s going on in our museums around the art of this region, otherwise it goes unnoticed,” laments Laure d’Hauteville. “With the current Israel-Hamas conflict, we see very harsh images on social networks, but also artists expressing themselves. That’s how people spot them and start to follow them.”

Cancelled

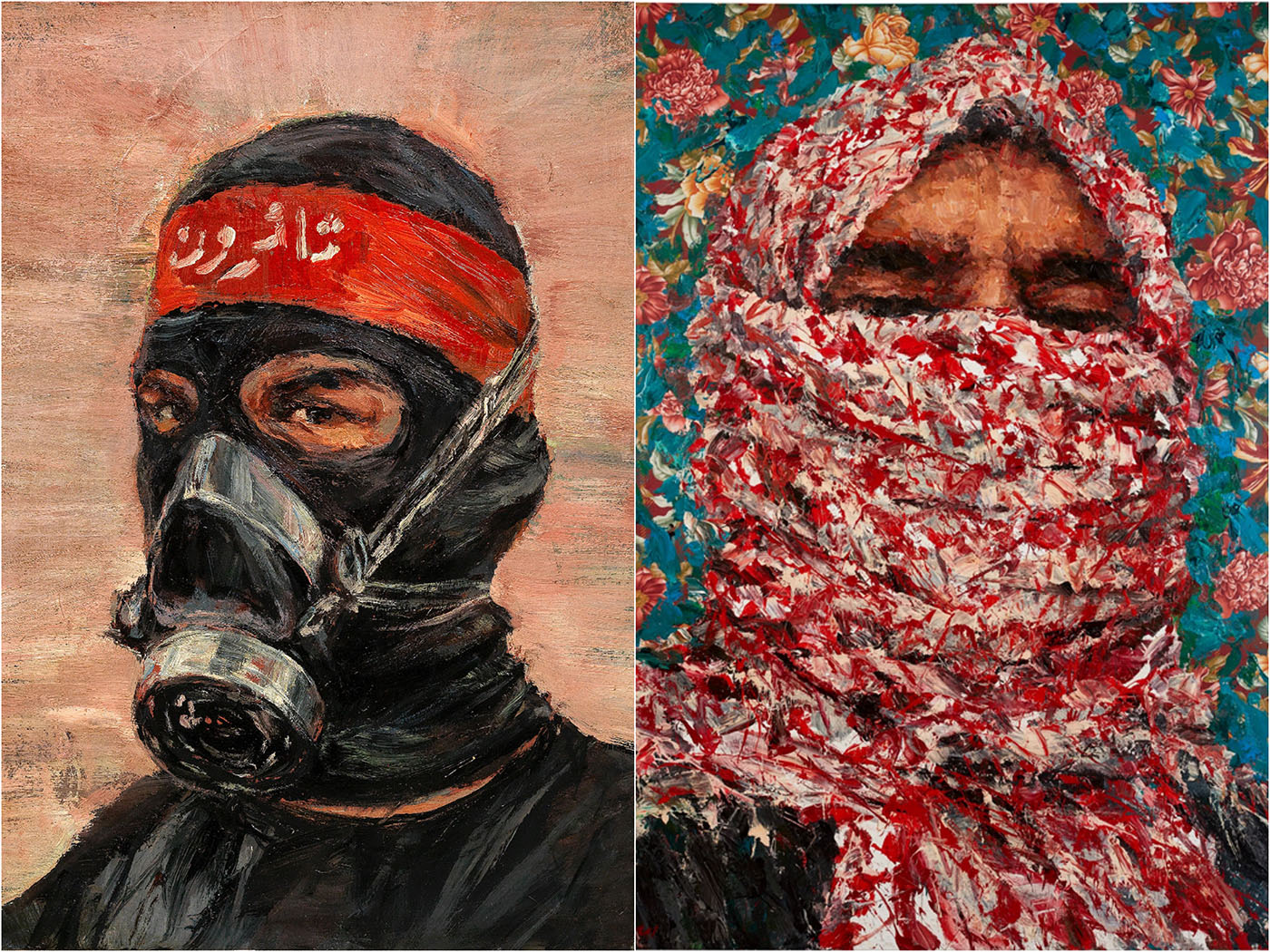

Earlier this month, two paintings by Lebanese painter Ayman Baalbaki were withdrawn from a Christie’s auction in London, because they were (erroneously) associated with Hamas and Islamic terrorism. One portrait, “Al Moulatham,” of a peasant whose face is wrapped in a red keffiyeh to protect him from the sun, was painted by the artist in 2012. The second shows a demonstrator in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, wearing a gas mask, with the Arabic inscription tha’iroun, “rebels,” on his forehead. Baalbaki was quick to retort publicly in the media that these removals reminded him of the Nazi reaction to “degenerate” art.

Paradoxically, the artist, until then primarily known in the Arab world, gained international recognition as a result of this incident. “The two paintings withdrawn from the public auction were sold privately,” says art historian Rose-Marie Ferré. “This is a very hypocritical act on the part of the auction house, which has taken a political stance without any historical, contextual or critical basis. It’s not possible to withdraw an image, and it’s up to art connoisseurs to explain it.” Since then, the controversy has made people talk about the work of the artist, whose work has never sought to adapt to the international market, nor attempted to please anyone.

“We’re living in a global world where juxtaposed identities are highlighted, creating areas of friction. For my part, I prefer to talk about roots rather than identity, because when artists get hold of identity-based discourse, it becomes dangerous,” continues Rose-Marie Ferré. “I like it when people talk about roots, commitment and shared values. Realizing that there are committed artists elsewhere in the world helps us understand that there is another history of art to be written, other forms of exhibition to be set up. Conflict allows for the construction of dialogues, but also the decentering of perspectives. The academic also points out that some of the Middle Eastern artists invited are reluctant to express themselves on this conflict, for fear of being taken to task.”

However, these cancellations are not limited to artists from the Middle East. In November, Norwegian director Mats Grorud received an email from the Paris education authority informing him that all school screenings of his film The Tower had been cancelled. The feature-length animation, which has won awards at numerous festivals around the world, including Annecy and Guadalajara, tells the story of young Wardi, a resident of the Burj el-Barajeneh Palestinian refugee camp in Beirut, whose great-grandfather, Sidi, was driven off his land in 1948. The day Sidi leaves her the key to his former home in Galilee, Wardi fears that he has lost all hope of ever returning home. As she tries to find Sidi’s lost hope around the camp, Wardi gathers testimonies from her family, from one generation to the next.

Silenced Voices

“There is a difference between the content broadcast in Arab media like Al Jazeera, and most media in Europe,” notes Mats Grorud in our conversation. “During screenings in Norway with children and teenagers from the MENA region or sub-Saharan Africa, I realized that my film offered a vision closer to the narratives heard at home. By showing the Palestinians’ point of view and their experiences, it’s like finally recognizing reality as they see it.”

Before making The Tower, Grorud spent a year in the Burj el-Barajeneh refugee camp in Lebanon, home to some 400,000 refugees who left Palestine following the Nakba, the forced exile of the Palestinians in 1948. Like the Gazans, they have been there for four generations. “The last thing that happened in Gaza was the Great March of Return,” says the director. “The images of children throwing stones don’t come out of nowhere. This population has been trapped in camps for 75 years. The Palestinians have been abandoned by the whole world. They could stay there for centuries and nobody would care…Palestinian and Jewish voices for peace are often silenced in many European countries, especially France and Germany, which are marked by a strong sense of guilt due to their Nazi past,” Mats Grorud argues. “Boycotting us is an infringement of freedom of expression. All we’re asking is that the United Nations conventions be respected, and that the refugees be allowed to return to their country and live there in freedom. There’s nothing radical about this, it’s simply about respect for human rights.”

Oppressive Atmosphere

There have been numerous cancellations or attempted cancellations in Europe and the United States. This November, the horrifying images of the October 7th attacks were screened in Hollywood, as well as at the French National Assembly and Senate. On the other hand, the documentary Yallah Gaza, directed by the Frenchman Roland Nurier in collaboration with the Gazan documentary filmmaker Iyad Allasttal, was the subject of an attempted ban on its theatrical release on November 8 by the French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin.

In addition, broadcaster ARD canceled the premiere of Palestinian director Anne-Marie Jacir’s film Wajib, scheduled for November 19 on German television, and the work of American trans neuroqueer Anaïs Duplan, founder of the Center for Afrofuturist Studies in the USA, was deprogrammed by the director of the Folkwang Museum in Essen, following an Instagram post in support of the Palestinians.

The boycott comes amid growing sympathy for the Palestinians, as images of the Israeli army’s massacres in Gaza spread and the civilian death toll rises exponentially. Lately, in the United States, some Wall Street and Hollywood billionaires are mobilizing to preserve sympathy and support for the State of Israel, as reported by the independent media Semafor. A recent survey by the University of Maryland and Ipsos revealed that the wave of support for Israel since the October 7 attacks is not shared by younger, liberal Americans. This is demonstrated by the wave of pro-Palestinian student demonstrations across the country.

The Power of Art

“Curators and collectors construct art history,” concludes teacher-researcher Rose-Marie Ferré. “As they are committed, they will promote certain artists in line with political positions. Geopolitical unrest therefore has a direct impact on the orientations, discourses and images promoted at events. Art has power, otherwise artists wouldn’t be thrown in jail.”

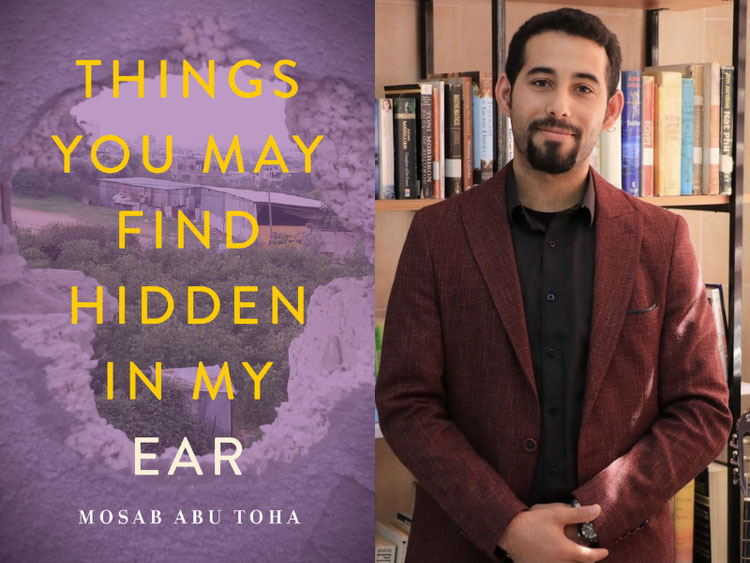

To cap off weeks of drama for artists and writers supporting Palestinian rights, last week the IDF arrested Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha in Gaza. Abu Toha is the winner of the American Book Award and finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. The 30-year-old writer has written searingly about the Israeli air strikes that have decimated Gaza since the war between Israel and Hamas broke out last month. In an essay published by The New Yorker on October 20, he described his return home to Beit Lahia, in northern Gaza, a few days after being evacuated to the Jabalia refugee camp, where he had been staying with relatives.

“On the main street leading to my home, I discover the first of many shocking scenes. The store where I used to take my children to buy fruit juices and cookies is in ruins. The freezer, which once held the ice creams, is now filled with rubble. I smell explosives, and maybe flesh,” he writes.

Beaten and the worse for wear, Abu Toha was released two days after being detained, as a result of a storm of protest across social media. He reunited with his family, but the IDF confiscated his passport and the passports of his wife Maram and three children, the youngest of whom was born in the United States and is therefore a US citizen.

Powerful. Thank you.