Select Other Languages French.

This isn't just a "Third World problem," for wherever there is love, there have always been social and religious conventions standing in its way — frequently enforced by those closest to the lovers. Forbidden love isn’t a trope for nothing.

Dear Souseh,

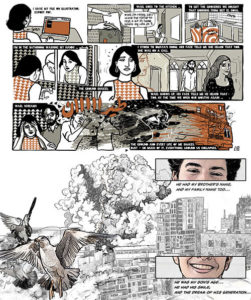

I’m a Lebanese Shiite woman who has been in an interfaith relationship with a Christian man for three years. We met on a discussion forum during the Lebanese uprising of 2019. I wrote a post that railed against the corruption of the sectarian system, and the collective numbness of our society; he sent me a private message telling me he was inspired by my passion, and one thing led to another.

It was super easy to talk to him, I found that we agreed politically on so many things, especially our frustration with the conservative expectations that shape most of our lives. During one of our first chats, he told me, “It’s pretty bold of you to still want to get to know me even after I revealed my ultra-Crusader Christian name.” I laughed aloud; this only made me appreciate him and his sense of humor even more, though I was admittedly afraid things might not work out between us. We’re both totally secular and leftist, but in Lebanon, religion isn’t so much about faith but culture and community. I knew this would become an issue, sooner or later. Still, I fell hard. He’s kind, loyal, romantic, and generous in ways I’ve never known.

From the beginning, we’ve talked openly about the challenges. But lately, the discussions have become increasingly tense, because he keeps reminding me that the ball is mostly in my court, since it’s my father and his opinions standing as an obstacle in the way of moving our relationship logically forward into marriage. He expects me to stand up for him and stand up to my father. To fight for our love. But the thought of telling my father about us feels like stepping into a crazy storm that’s going to cause mayhem in our household.

What I also can’t seem to get across to my partner is that I don’t see it as one fight to get my father to accept him. Because even if he does eventually, there’s the reality of blending our two families. He claims his family is totally open, and while they’ve definitely been polite and accommodating and have included me in a lot of different things, they’ve also revealed all these subtle biases through offhand comments and behavior that I can only call “Islamophobia lite.” Then there’s also political differences. His father leans Phalangist (while mine let’s say supports everything the Phalangists stand against). I wish I could believe in my partner’s idea that “love conquers all.” But marriage is something else.

Sometimes he seems to understand all of this perfectly, and I feel like he’s being supportive and empathetic of my difficult position and hence my hesitation. But then in other cases he shows me that he doesn’t get it at all. In these moments I become aware of his immaturity (which is also manifest in other ways). He wants us to move forward. He says it should be simple.

I know the longer I drag this out the more hurt he is. And I hate hurting him. I’d also be devastated to lose him. But I also hate the idea of hurting my dad, with whom I’ve always been very close. I feel really stuck. I see a future where every choice will be shadowed by approval or disapproval, subtle judgments, and the emotional cost of trying to fit two worlds together. I guess I’m wondering if it’s worth all the trouble. Is it really as simple as he says? Do I just have to take a chance on love? He says that all my rebellion against social convention is just empty talk if I won’t practice it where it counts: in my own family. Is he right? Am I being pragmatic or am I a coward who won’t choose love over fear?

Signed,

Stuck Between Families

Dear Stuck Between Families,

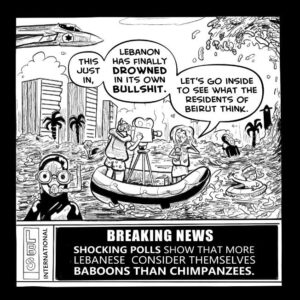

If Lebanon had just 100,000 LL for every star-crossed interfaith couple in love, it would have enough to pay back every depositor whose money it stole, and then some. I don’t say this to be dismissive or make light of your situation, only to point out that — as you must know — you are definitely not alone. Not in a place like Lebanon, where, with 18 different recognized sects and a long and complicated history of political misalignment between them, the situation is both more commonplace — but admittedly sometimes more complex — than it might be elsewhere. And of course, it is a situation that exists elsewhere, or rather, everywhere. Wherever there is love, there are (and long have been) social, political, religious and economic boundaries standing in its way, often enforced by those closest to the lovers. Forbidden love isn’t a trope for nothing.

But your question, and your situation, is a lot more nuanced, I think, than that of a straight-up forbidden love. It seems to me that the obstacle here is not so much your father as it is your own doubt about your compatibility as a couple, which is to say, the lack of compatibility between the family you come from and the family you wish to make. We think of couplehood as this intimate space that fits only two people, but in fact there is very little of a romantic relationship when a couple is entirely alone. That is, cocooned inside their togetherness, ensconced in the feeling that they are the only two people in the entire world. It strikes me that this is really what characterizes “the honeymoon phase.” The love is at its most heightened, purest state not just because it is still new, but because the world hasn’t intruded on it yet. As soon as the couple steps off of Cloud 9 and onto the asphalt of the daily grind — which is a process that happens gradually, rather than all at once — there are other ambitions and desires to figure out how to prioritize, other people to contend with, an entire context to have to navigate. The couple bumps into, runs into, is pushed and jostled by the materiality of the surrounding world, and all of it has to be confronted both together as a couple and alone as individuals.

This is the “something else” of marriage that you so rightfully point out. Marriage means choosing the partner with whom you will exist in community. And existing in community is a constant balancing act. One can say that it is the hardest balancing act of a life, the one which has to be calibrated consistently and eternally. How do you weigh individual desire against community harmony? What price are you willing to exact from one in order to buy yourself peace in the other? Those who say “follow your heart” or “love conquers all” often have a very narrow and individualistic perspective of things. Because no heart runs on a single desire, nor is championed by a single love. For example, your heart here is obviously telling you many things, some of them contradictory. You don’t want to hurt your dad. You don’t want to hurt your partner. You don’t want to hurt yourself. Which is the right path, among all these piercing thorns? I’m not saying there is absolutely no way to navigate any of this. To ask “what is the path” is not to say that there is no path at all. It is to acknowledge that there are in fact many paths, and each one is going to mete out its own wounds. Some that you can anticipate from where you’re standing, and some you absolutely cannot.

I think you’re right in saying that this is not one single fight about getting your father to accept your relationship, but many fights over the course of a lifetime. Just going by the interfaith couples I’ve known in my own life in Lebanon, I can think of dozens of questions just off the top of my head that you’re going to have to contend with. Starting with: how will you get married? Will either of you have to convert so you can get married on Lebanese soil? Will you have to go to Cyprus and have a civil ceremony? Then, when you have kids (provided of course you want to have kids), will his parents expect them to be baptized? Would your parents accept such a thing? Say all of this is somehow resolved. Say your father and his father decide, for the sake of harmony, to never discuss politics with one another during family gatherings, regardless of circumstance (which seems to me the most unbelievable fantasy of all, but let’s go with it). What happens if there’s civil strife in the country? What if the worst happens and it plunges (anew) into civil war? Will the Phalangist and anti-Phalangist drift away from whatever middle ground they’ve been able to meet on and take up hardline positions in their respective camps? What might that do to the family then?

None of these are easy questions. Nor do I think that any of them are insurmountable either. In theory. In theory, nearly every issue can be negotiated with patience, willingness and time. I’ve seen enough interfaith couples negotiate them to know this. And also to know that, in practice, the only way to do so as a couple is, well, as a couple. You need to be partners in every sense of the word. In any us-against-the-world dynamic, the only way to have a fighting chance is to have a really strong, united, near-indivisible us. Otherwise, the world wins, every time.

How does he navigate his family’s attitude toward you? Does he validate your discomfort with their views or discount it? After all, it’s easy to identify and reject sectarianism when it’s part of a political and financial system that dictates quotas and alliances and economic interests. Harder when it is manifest in subtle glances, offhand comments, dismissive attitudes, and casually dehumanizing statements (again, I’m going by my own experience and understanding of all the flavors of “sectarianism lite” that I’ve encountered in Lebanon). He seems to have created this dichotomy in his mind where your family is closed and his is open. If he can’t see that you’re both facing the same kind of challenging attitudes (with admittedly vastly different manifestations) then of course it’s easier for him to throw the entire burden of “fighting for your love” on you. This will build resentment in both of you over time: in him because you refuse to fight, in you because he refuses to see. It sounds like this process has already begun. And nothing crushes the delicate bloom of romance like the weight of resentment.

Does he appreciate the fact that you will be the one to bear the brunt of this decision? That you will be the one upending your nuclear family and then having to live with the fallout from that? It’s simple to say what we’d be willing to do or not do when the cost is theoretical, or will be borne by someone else. That said, I also have a lot of compassion for his frustration. It’s clear that he loves you and is committed to building a future with you. And your hesitation about moving forward is painful, because fundamentally — and he knows this — your hesitation is about him. Your commitment to him. Of course he’s going to feel rejected and upset. He has every right to feel this. What he doesn’t have a right to do is lash out and try to emotionally manipulate you by calling you a coward and a hypocrite. To me, it is this that is most indicative of his immaturity. Not the fact that he thinks love should be simple.

This is very much the dilemma of an interfaith relationship, but the faith the two of you seem to be misaligned on is faith in one another. In your ability to navigate life together. A system of faith is the structure we impose on the chaos of the world in order to give it shape and pattern and meaning, to give us a scaffolding to hold on to when the darkness is thick and blinding. Whether faith in religion, or political cause, or people at large, faith is the larger, pre-set system of belief that we can cling to during those times when it feels like there’s nothing to believe in. Thus, faith shapes reality itself, because it shapes how we perceive reality.

You can love someone but not have faith in them. It’s faith that gives love its longevity, that helps it endure during the difficult times when it seems less like an active feeling and more like a passive habit. Faith that your partner will have your back, will argue or even get mad at you without ever thinking less of you, will steadfastly hold your best interests at heart as you will theirs. Faith can be blind and cruel and unyielding as equally as it can also be wise and cultivated through experience. Either way, it forces you to take a leap, because it’s a belief in something that extends out into the unknown of time. Faith is a bridge over the darkness of the unknown. We can’t see what will hold us as we step out into time, but we believe, believe to the point of knowing, that something will. And so the question for you is not should you have faith in this man. It is very simply: do you have faith in this man? This is the belief that will shape your reality with him moving forward. There is no right or wrong answer. It’s something you have to believe. That’s the only way you’ll have stamina enough for the fight going forward. And yes, it is a fight. But it’s a fight that can be won. Even in a country as stubbornly sectarian as Lebanon, plenty have fought this battle and been victorious.

You must ask yourself: Does this man have what it takes to fight by your side? But also: do you have the faith required to fight by his? If you can answer those questions honestly, then you’ll come to know whether the strength you need to summon now is the strength required to move forward or the strength to walk away.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)