Agha Shahid Ali

Tonight

Pale hands I loved beside the Shalimar

—Laurence Hope

Where are you now? Who lies beneath your spell tonight?

Whom else from rapture’s road will you expel tonight?

Those “Fabrics of Cashmere—” “to make Me beautiful—”

“Trinket”—to gem—“Me to adorn—How tell”—tonight?

I beg for haven: Prisons, let open your gates—

A refugee from Belief seeks a cell tonight.

God’s vintage loneliness has turned to vinegar—

All the archangels—their wings frozen—fell tonight.

Lord, cried out the idols, Don’t let us be broken;

Only we can convert the infidel tonight.

Mughal ceilings, let your mirrored convexities

multiply me at once under your spell tonight.

He’s freed some fire from ice in pity for Heaven.

He’s left open—for God—the doors of Hell tonight.

In the heart’s veined temple, all statues have been smashed.

No priest in saffron’s left to toll its knell tonight.

God, limit these punishments, there’s still Judgment Day—

I’m a mere sinner, I’m no infidel tonight.

Executioners near the woman at the window.

Damn you, Elijah, I’ll bless Jezebel tonight.

The hunt is over, and I hear the Call to Prayer

fade into that of the wounded gazelle tonight.

My rivals for your love—you’ve invited them all?

This is mere insult, this is no farewell tonight.

And I, Shahid, only am escaped to tell thee—

God sobs in my arms. Call me Ishmael tonight.

At the Museum

But in 2500 B.C. Harappa,

who cast in bronze a servant girl?

No one keeps records

of soldiers and slaves.

The sculptor knew this,

polishing the ache

Off her fingers stiff

from washing the walls

and scrubbing the floors,

from stirring the meat

and the crushed asafoetida

in the bitter gourd.

But I’m grateful she smiled

at the sculptor,

as she smiles at me

in bronze,

a child who had to play woman

to her lord

when the warm June rains

came to Harappa.

Zaynab’s Lament in Damascus

Over Hussain’s mansion what night has fallen?

Look at me, O people of Shaam, the Prophet’s

only daughter’s daughter, his only child’s child.

Over my brother’s

bleeding mansion dawn rose–at such forever

cost?

So weep now, you who of passion never

made a holocaust, for I saw his children

slain in the desert,

crying for water.

Hear me. Remember Hussain,

what he gave in Karbala, he the severed

heart, the very heart of Muhammad, left there

bleeding, unburied.

Deaf Damascus, here in your Caliph’s dungeons

where they mock the blood of your Prophet, I’m an orphan, Hussain’s sister,

a tyrant’s prisoner.

Father of Clay, he

cried, forgive me. Syria triumphs, orphans

all your children. Farewell.

And then he wore his

shroud of words and left us alone forever.

Paradise, hear me–

On my brother’s body what night has fallen?

Let the rooms of Heaven be deafened, Angels,

with my unheard cry in the Caliph’s palace:

Syria hear me

Over Hussain’s mansion what night has fallen

I alone am left to tell my brother’s story

On my brother’s body what dawn has risen

Weep for my brother

World, weep for Hussain.

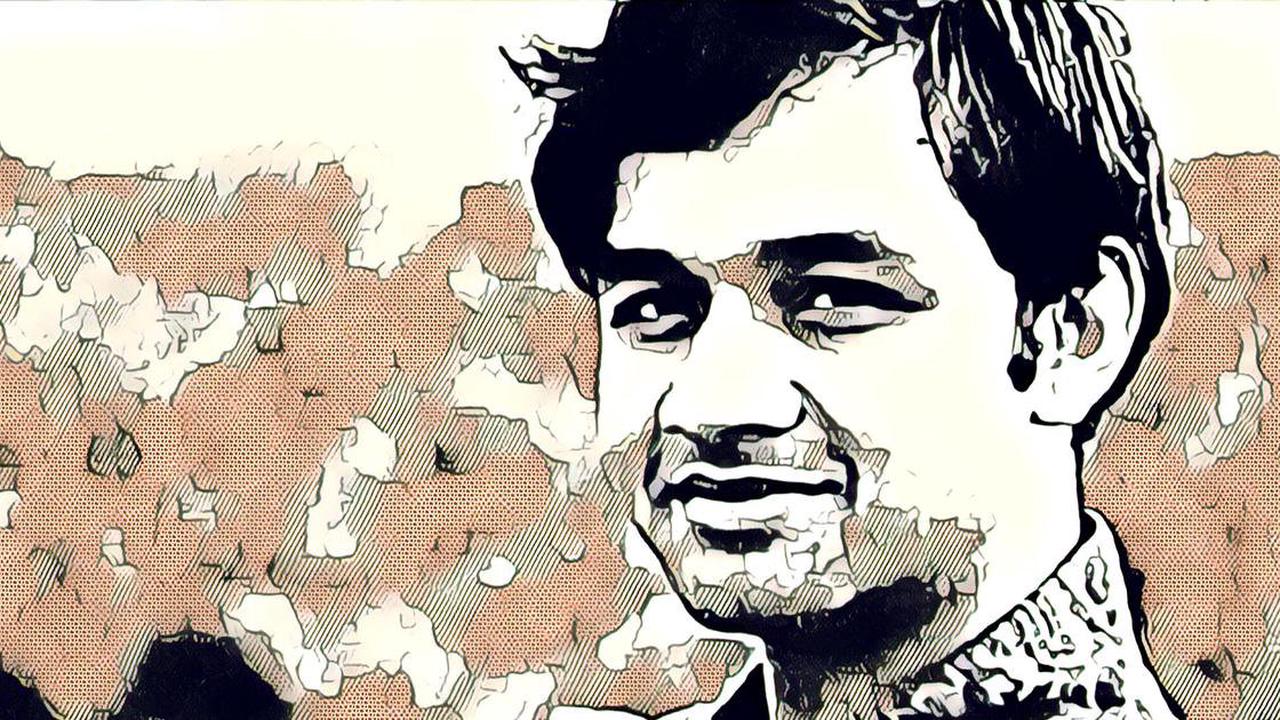

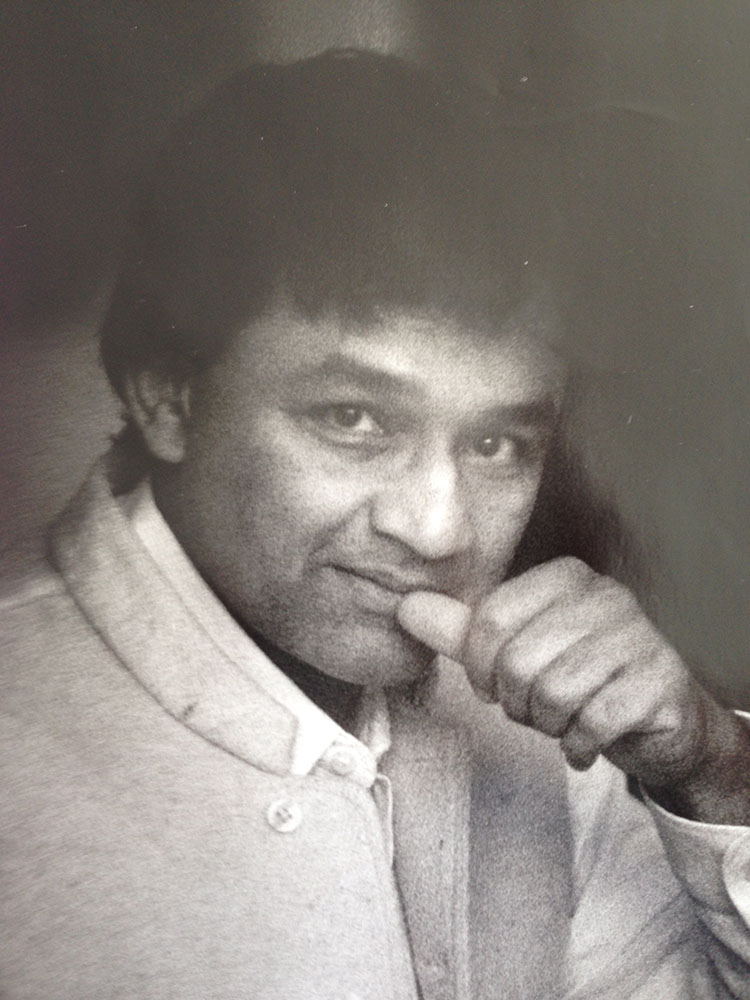

Agha Shahid Ali (b. Delhi 1949; d. Amherst 2001), was an American poet, gay, Shiite, secular, from a highly educated family from Srinagar, who later lived near him in the United States as well (and who affectionately called him Bahiya). He grew up in Kashmir, then attended university in Delhi and in the United States. He wrote a thesis of literary criticism on TS Eliot (and admitted playfully that he was bored and hooked on One Life to Live at the time), translated the celebrated Urdu poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz (The Rebel’s Silhouette, 1992), wrote nine books of poetry, and taught and directed creative writing programs at Hamilton College, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, with stints at NYU and Princeton. He read his poetry to raptured audiences internationally, and his collection Rooms are Never Finished (2001) was a National Book Award finalist.

His poetry is stunning, with not a boring moment. It is remarkable for its breadth, steeped in cultural artifacts and reflections — Urdu, Hindu, Kashmiri, Syrian, or Andalusian – about longing, love, displacements both mythical, historical, and current. Composing unabashedly dramatic, lyrical poetry, Shahid sustains buoyancy, humor, and an uninterrupted sense of the absurd. He was life-long friends with poet James Merrill, naturally collaborated with artists and writers, loved recounting experiences of wonder and delirium, of Urdu poetry, or what it was like to attend the concerts of Begum Akhtar. He was at ease with all these elements together, and wrote free-verse and ghazal poetry with equal fluency and originality, weaving mythical, historical, biblical, koranic references in a modern American idiom. Rendering these vast expanses of time and geography meaningful to all, he grounds us in a vernacular sensibility.

When he was at University of Massachusetts at Amherst he would regularly decide to cook for his friends, and the next day invite them as he passed by, laughing and joking and welcoming, until he had some 40 people due to appear on his doorstep the next evening. He would start cooking at 8 am, giant pots of Kashmiri stews and rice and a mountain of tangy salad diced so finely. We would all sit on the floor and eat with our hands from a rimmed metal platter—Shahid’s gift, and our spiritual initiation into hot hot food, his magical worlds and presence. He was curious and magnetic, holding his geographies, languages, diverse friendships, and artistic influences in effortless simultaneity, with warm humor, like no one I had ever met before or since. He was funny, hugging and kissing the many he loved, disarming everyone. (He once admitted to Edward Said in a car journey with his CDs playing that European classical music “bored him to tears,” and of course Edward was fascinated, and not offended, as much by Shahid’s alien tastes, I imagine, as by his naughty frankness.) Once in Northampton we only found an Italian restaurant open for dinner on a Sunday and he threw me a stricken glance, remarking that Italian food (likewise) “bored him to tears.” We went home and ate my leftover maqloubeh instead (“it’s subtle,” he commented diplomatically after taking a bite from the pan, arching his brows comically), and he was happy as a lark once I added lots more spice and hot peppers.

Shahid was magnanimous, and grounded somehow, in both his art and person: he felt Kashmiri, proud of his warm family, at once culturally Shiite and secular, considering himself an American poet, and persistently interconnecting his worlds both inherited and adopted. He left us with an oeuvre of beauty, distinctiveness, and surprise. Once you start to listen to or read his poetry it begins to inhabit you, draw you into dreams, prehistoric worlds, antiquity, tragic loves and empires lost, from the Tucson desert to Kashmir, Amherst, Palestine, and back again to the beginning of time. Beloved Witness is the title one of his poetry books, all puns, evoked by writers and fans to refer to him.

—Jenine Abboushi

Marseille, 2021