Select Other Languages French.

The 2025 Azhar Writing Prize second-place short story about innocence lost begins in a 1945 Arab-Jewish village. The daughters of Diba’s neighbor disappear, sparking gossip and speculation. As she and her family prepare to flee during the Nakbah, a jolt of recognition only strengthens her resolve to return to her home.

April 1945. Mount Carmel, Haifa

The late afternoon sun shone lazily through the wrought iron grill of her kitchen windows as Diba grabbed the handle of the rakweh filled with bubbling coffee from the stove. She walked back to the wooden table where Amal sat waiting with unmasked impatience. Diba poured the steaming liquid into the two pre-set porcelain cups slowly and deliberately, utterly at odds with her neighbor’s disposition.

“Tayeb?!” Amal demanded. “Got any theories?”

Diba clicked her tongue to signify that no, she didn’t. While many women of the village relished such gossip sessions, Diba was not one of them. She was a rare breed who — in practice and not only in words — ascribed to the saying Allahuma la shamata. Do not gloat at the misfortune of others. The phrase was religious in origin, though it was no claim to religiosity that made Diba loathe to gossip. Rather it was a combination of her staunch empathy and her inability to countenance frivolous chitchat. She would sooner be discussing the latest activities of the Arab Women’s Union, which had just established the first prenatal clinic in Jerusalem. Diba did sometimes encounter women in the village interested in such discussions; Amal was not one of them.

“Wafaa thinks they’ve found themselves a couple of boyfriends in another town. But how is their mother allowing this? And their brother?! Only Allah knows.” Amal spat out the last few words as though pondering the deeds of a mass murderer.

The subjects of Amal’s ire were the daughters of their Jewish neighbors, the Sahalons. Their house was just down the hill, clearly visible from the vantage point of both Diba and Amal’s. Over the last few weeks, villagers had noticed prolonged overnight absences on the part of the two girls, Laila and Maryam. Given they were of marriageable age, this was unheard of in the village. Amal took a pronounced sip of coffee, raising her eyebrows in eager anticipation. But she would be disappointed.

“Why judge something we haven’t the least idea about?” Diba half-asked, half-stated, knowing that nothing would quell Amal’s voracious curiosity.

Diba liked the Sahalons. Not close friends, but courteous neighbors. She enjoyed the short exchanges she had with Tamar, the mother of Laila and Maryam, when they crossed paths. Tamar’s son, Sulaiman, would sometimes kindly offer to carry Diba’s overflowing basket of vegetables when he would spot her walking back from the souq. He was a handsome young man, and Diba pretended not to notice when her own daughters subtly jostled over who would receive the basket from him at the doorway. Diba was confident that her girls knew better than to ever act upon such infatuations. Although this new generation did seem far more audacious than Diba was ever taught, or indeed allowed to be. It frightened her. She was all aboard with AWU’s talk of equal rights and increasing women’s participation in the workforce. But could she ever countenance her own Basima, Feryal, and Fadia becoming the gossip of the town over afternoon coffee?

“Yalla, read it ya hakima, tell me what’s in store for me.” Amal handed over her empty coffee cup for Diba to read her fortune, a ritual that had grown between them over the years of companionship by proximity. “Or better yet — have a look for those girls and their secrets!”

March 1948.

The sound of gunshots was ceaseless. Diba couldn’t tell how close they were, only that they made her jump every single time.

“YALLA ya banat!” Diba called out to Feryal and Fadia as she haphazardly placed a ladder under the traditional sidde storage space, climbing it swiftly to grab some ma’amoul. She had no idea how long this journey might take and didn’t want to be at the mercy of circumstance. She could hear her daughters panicking; wailing; screaming; as they gathered what they could. Diba on the other hand was mostly silent, eerily calm, moving in a dreamlike state.

“But what about Baba, aren’t we waiting for him?” Fadia sobbed as she appeared in the kitchen, arms overflowing with thobes and useless trinkets. Diba’s husband, Sameer, had left the previous evening to join the Palestinian volunteers fighting the Carmeli Brigade of the Haganah, who had just initiated a full-scale attack on their village. She had no word from him. No idea if he was still alive, let alone coming back. She promptly swallowed the lump in her throat that threatened to surface and destroy her entire world.

“Yalla,” Diba repeated quietly but firmly as a speeding vehicle ground to a halt outside. She picked up the overstuffed case, hoping she’d made the right choices for both herself and Sameer, refusing to consider the possibility she had packed for a dead man. Marwan, her daughter Basima’s fiancé, managed to procure a truck to take the family to the port to escape to Lebanon — just until safety was restored. The three women hurried outside, but as Diba turned back to lock the door, she spotted Tamar walking up the hill flanked by what appeared to be two militiawomen. The sight of the uniforms and rifles slung across their chests sent an ice-cold chill down Diba’s spine, freezing her to the spot. As they came closer, her breath caught, the wind knocked out of her.

The militiawomen were none other than Laila and Maryam. They stood right in front of her, their mother in between. Diba was unable to move, to utter a word. But she didn’t have to.

“Unfortunately all your little gossip wasn’t true,” Tamar spoke with a new hardness, “The girls were not ‘having fun at the expense of our family’s honor.’ They were learning how to fight, to honor us. To build our country.”

Diba couldn’t help but look directly at Laila and Maryam. She remembered them as little girls, racing each other up the hills. Helping during the olive harvest alongside Diba’s daughters. The youngest, Laila, met her eyes momentarily but immediately looked down. Maryam looked straight back at her, her eyes impenetrable.

“Salam,” said Tamar before all three turned to walk back down the hill. Fighting back tears of rage and grief on fire, Diba locked the door with shaking hands and walked her family to the waiting truck.

Having stowed their belongings, Marwan beckoned the four women to get in the cargo bed. Diba glanced back at the house as her daughters climbed in. She turned to follow them and didn’t look back again. She didn’t need to. She knew they would be coming back.

“Diba’s House” is a fictionalized retelling of true events that occurred in Sara Masry’s ancestral village of Wadi Salib, which her great-grandmother, Diba, passed down through oral histories.

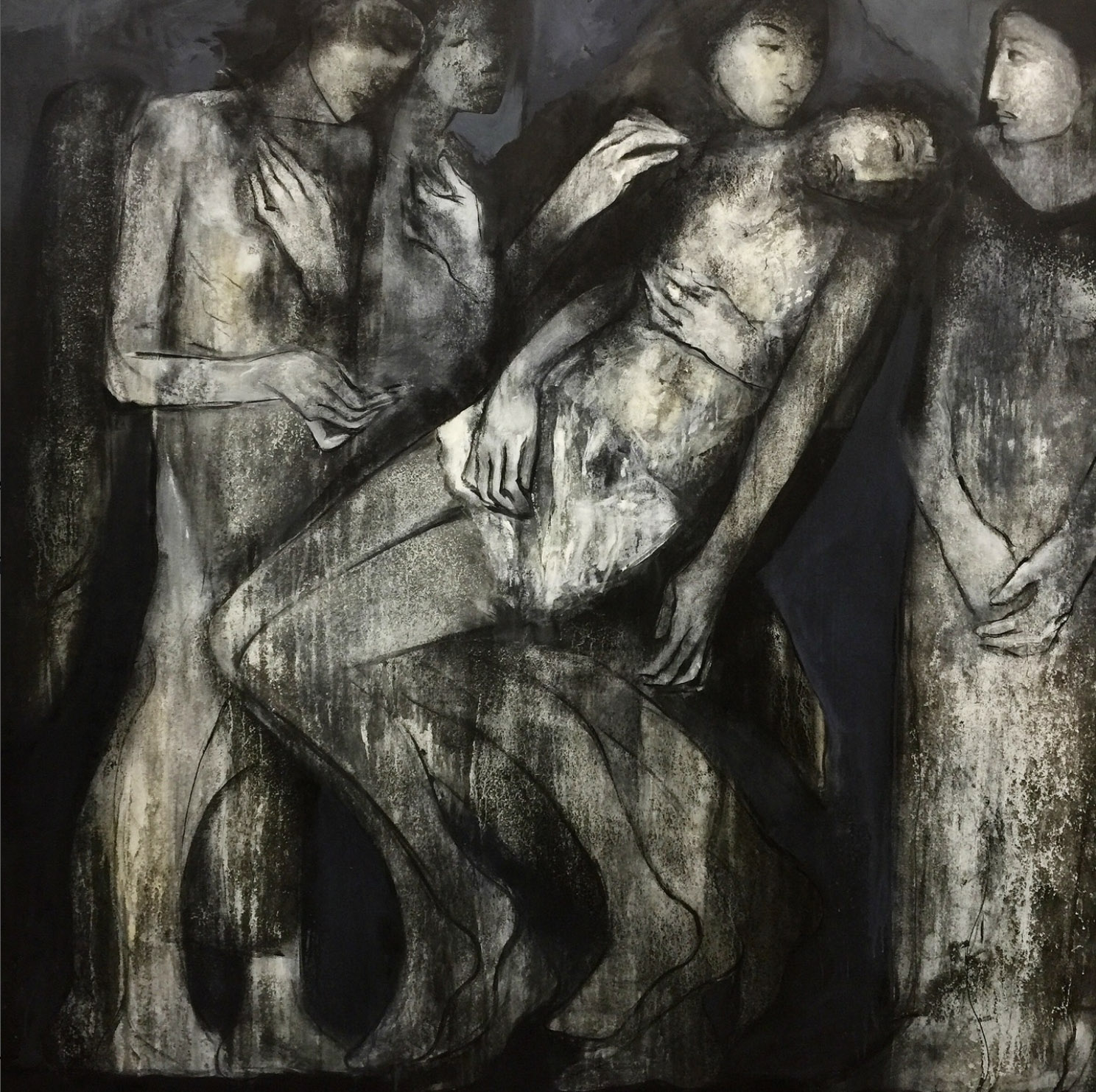

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)