Neve Tzedek, “Red City” Tel Aviv (Photo: Liran Sokolovski Finzi, Getty Images).

A Photographic Interrogation of the City’s Curated Image

Taylor Miller

To pierce the Tel Aviv bubble. The excitement, levity and coolness — the attitude and aesthetic that is cultivated and conveyed throughout the city — abounds in Neve Tzedek. It is one of several southern neighborhoods that, utilizing practice-based methods, I interrogate for the ways in which cultural hegemony is reproduced and weaponized in the arts-led gentrification of the city; one arm of the Zionist settler colonial hydra that continually displaces, erases, and reinscribes Palestinian space.

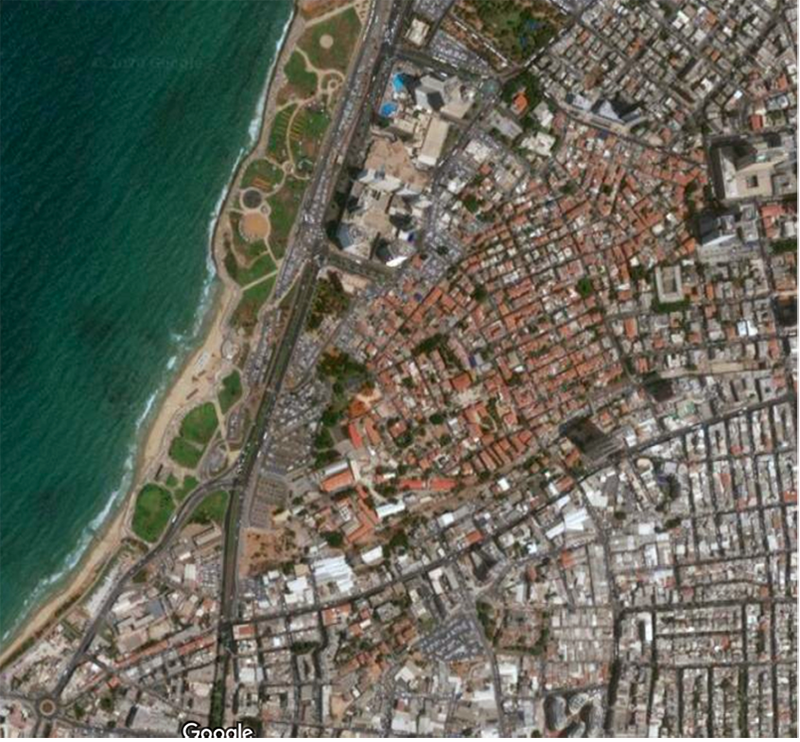

Figure 3.9. Satellite imagery of the “Red City” (Neve Tzedek) amongst the White City. The imagery is blurred because of the US Congress’s 1997 National Defense Authorization Act. One section is titled, “Prohibition on collection and release of detailed satellite imagery relating to Israel.” This is known as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment, whereby NOAA’s Commercial Remote Sensing Regulatory Affairs must control the dissemination of zoomed-in images of Israel, which prohibits US satellite imagery companies (like Google) from selling pictures that are “more detailed or precise than satellite imagery of Israel that is available from commercial sources” (Dance, 2019). The European Space Agency (ESA) has even poorer resolution of these sites.

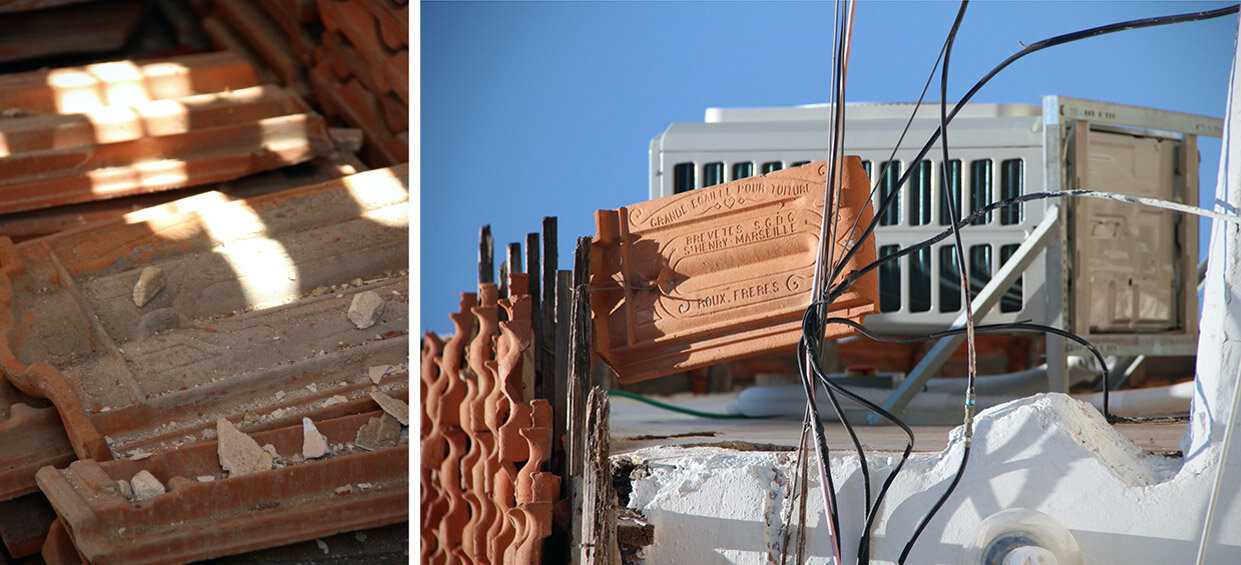

International Style architecture is not as prevalent here as in other neighborhoods in the city, but that does not mean that the impulse toward material and conceptual bordering isn’t there. While within the boundaries of the “White City” (for more, see: Rotbard, 2015), Neve Tzedek (and adjacent Shabazi) is sometimes referred to as a mini ‘Red City’ due to an abundance of distinctive red roofs. These terra cotta shingles were dubbed “Marseille tiles” (Fig. 3.9 – 3.13). Widely marketed for a timeless appearance — an “instant classic” — it is unclear whether the roofing in Neve Tzedek was imported from Marseille, France, or if the replicable style was brought in from elsewhere.

From the neighborhood’s founding, most buildings were only built one or two stories tall along narrow streets with tight alleys; Jugendstil and Art Nouveau elements were paired with International Style, and later, Bauhaus-influenced forms. Contemporaneously, the mixture of architectural styles makes for a disunified if not cluttered appearance. In part, this is because Tel Aviv’s northward sprawl throughout the 20th century drew affluent residents to newly developed exclusive enclaves and high rises (such as the present-day pockets of Park Tzameret and the “Old North”, the area north of Azlozorov Street, west of the Ayalon Highway). In the 1960s, officials labeled the neighborhood a slum as it was visually and materially incompatible with the sleek, bustling image of the rapidly globalizing city. Portions of the neighborhood were slated for demolition to make room for seafront apartments and retail, though these plans were shelved when some of the structures were placed on preservation lists.

Menachem Begin and the Likud Party’s policies, compounded by the thrum of neoliberalization that consumed Tel Aviv in the 1980s, increasingly positioned Neve Tzedek as a semi-pastoral, picturesque reprieve from the surrounding commotion. By decade’s end, arts-led gentrification initiated the neighborhood’s revamp as a polestar for fashion, boutique hotels, upscale cafes and design evocative of a Mediterranean anywhereness. Overgrown bougainvillea cascade over colorful street art and neo-Moorish arched windows. Purposefully blighted for decades, only to be redeemed by an influx of Israeli and international capital, it is palpable how the historic built environment of the neighborhood is currently revalued for its symbolic and economic potential. Although Neve Tzedek is a small neighborhood, two distinct cultural clusters feature a concentration of artscapes and architectures that are encouraging of sociospatial segregation and overt commodification of urban space: HaTachanah (hereafter: The Station) and Shabazi Street.

Figures 3.10 & 3.11 (all photos courtesy Taylor Miller, unless otherwise noted). Figures 3.12 & 3.13.

The retail complex now known as “The Station” was once the terminus for the Jaffa railway station. Inaugurated on May 24, 1891, the line was conceived to link the Mediterranean coast with Jerusalem. Jewish businessman Yosef Navon was principally responsible for its construction, but when he lacked the capital to execute the project’s completion, the Société du Chemin de Fer Ottoman de Jaffa à Jérusalem et Prolongements was established in Paris to finance and build the line. Metre gauge was imported through the Jaffa Port from France and Belgium. During World War I, the rail station served as a military headquarters for the Turkish and German armies before the heavier machinery was moved to Jerusalem. As the British advanced northward in 1917, many bridges that supported the railway were detonated. In 1918, the Palestine Military Railways of the British Mandate rebuilt some of the line, including the section between Jaffa and Lydda junction. After the Nakba, all services at the Jaffa station halted and eras of neglect ensued. In 2004, the Tel Aviv Municipality initiated a restoration project (completed in 2009) that converted the former station into a leisure and entertainment complex. By February 2017, construction on the red line of the Tel Aviv light rail was underway, with estimated completion in October 2021. This line — with 33 stations between Petah Tikva (northeast of Tel Aviv) and Bat Yam (south of Jaffa, on the coast) — passes just south of The Station, integrating portions of the original 1891 railway in Neve Tzedek.

“Here, the manipulation of culture is a simultaneous manipulation of history; while a handful of placards include Arabic translations of the Jaffa to Jerusalem railway’s story, there is zero indication of the land’s Palestinian tenure prior to the train station’s arrival.”

At face value, The Station is nothing extraordinary. Much like shopping malls in warmer climates around the United States, a series of disconnected storefronts are pieced together by an expanse of wood, stone and cement plaza. Directive signage — primarily in English and Hebrew — is placed to drive foot traffic towards dining and shopping. About twenty design/concept stores, several bars and restaurants, and a scattering of art galleries populate The Station’s grounds. Shade is sparse, spare several aged eucalyptus trees and the fronds of spindly palms. In my visits to the site, all occurring between May-August, the sun proves unrelenting. In addition to the brick and mortar buildings in the complex, several rehabilitated train cars are positioned on the now-defunct stretch of rail; relics stripped of their original utility and expectation now serve as lackluster exhibition spaces to tantalize unassuming tourists, and for diluted tales of rail travel and nation-building (Fig. 3.14 – 3.15). However, there is much to observed in the oft overlooked interstices of the Israeli built environment, even in sites crafted for indulgence and entertainment.

Figures 3.14 & 3.15.

Figures 3.16 – 3.24 further illustrate how arts-led gentrification of The Station represents the conscious and deliberate manipulation of heritage and culture “in an effort to enhance the appeal of interest of places, especially to the relatively well-off and well-educated workforces of high-technology industry, but also to ‘up-market’ tourists and to the organizers of conferences and other money-spinning exercises” (Kearns & Philo, 1993, p. 3). Here, the manipulation of culture is a simultaneous manipulation of history; while a handful of placards include Arabic translations of the Jaffa to Jerusalem railway’s story, there is zero indication of the land’s Palestinian tenure prior to the train station’s arrival. To walk around The Station’s grounds is to experience both the physical and discursive emptying and erasure of Palestinian space; this violence is magnified by the shared boundary fence with the Israel Forces History Museum. The Station could have built a solid wall — better delineating this art and leisure site from combat-worn artillery and vehicles — but instead, the simple chain link and barbed wire fence enables a sort of visual permeability and ever-present reminder of Israel’s military aggression.

Figures 3.16, 3.17, 3.18 & 3.19 (clockwise from upper left). Figure 3.20.

While a solid wall between the museum and The Station would not nullify the existence of such a shrine to brute force, nor compensate for erasure of Palestinian spaces and cultures of eras past, the deliberate choice of porous fencing glorifies the ongoing material and psychological occupation of Palestine. It is a site where cultural activities near-seamlessly enmesh with the residues of past wars and imminence of future violence. The ever-present optics of culture, commodity and conflict entwined are exemplary of Israeli settler colonialism; it is an ongoing project of urban usurpation that does not cease.

The discursive erasures in Neve Tzedek — upheld by informational placards and exhibitions about the Jaffa rail at The Station — and the physical reinscription of the site not only contribute to processes of dispossession and cleansing of historical Palestinian culture and property, but they continually deny contemporary Palestinian presence in Tel Aviv and nearby Jaffa. The Station is space organized according to settler-colonial logic; it is the imposition of ethnic and religious hierarchy and cultural hegemony upon the land and its inhabitants, and it is reinforced through the curated image conveyed to tourists.

Figures 21 – 24. Fig. 3.25.

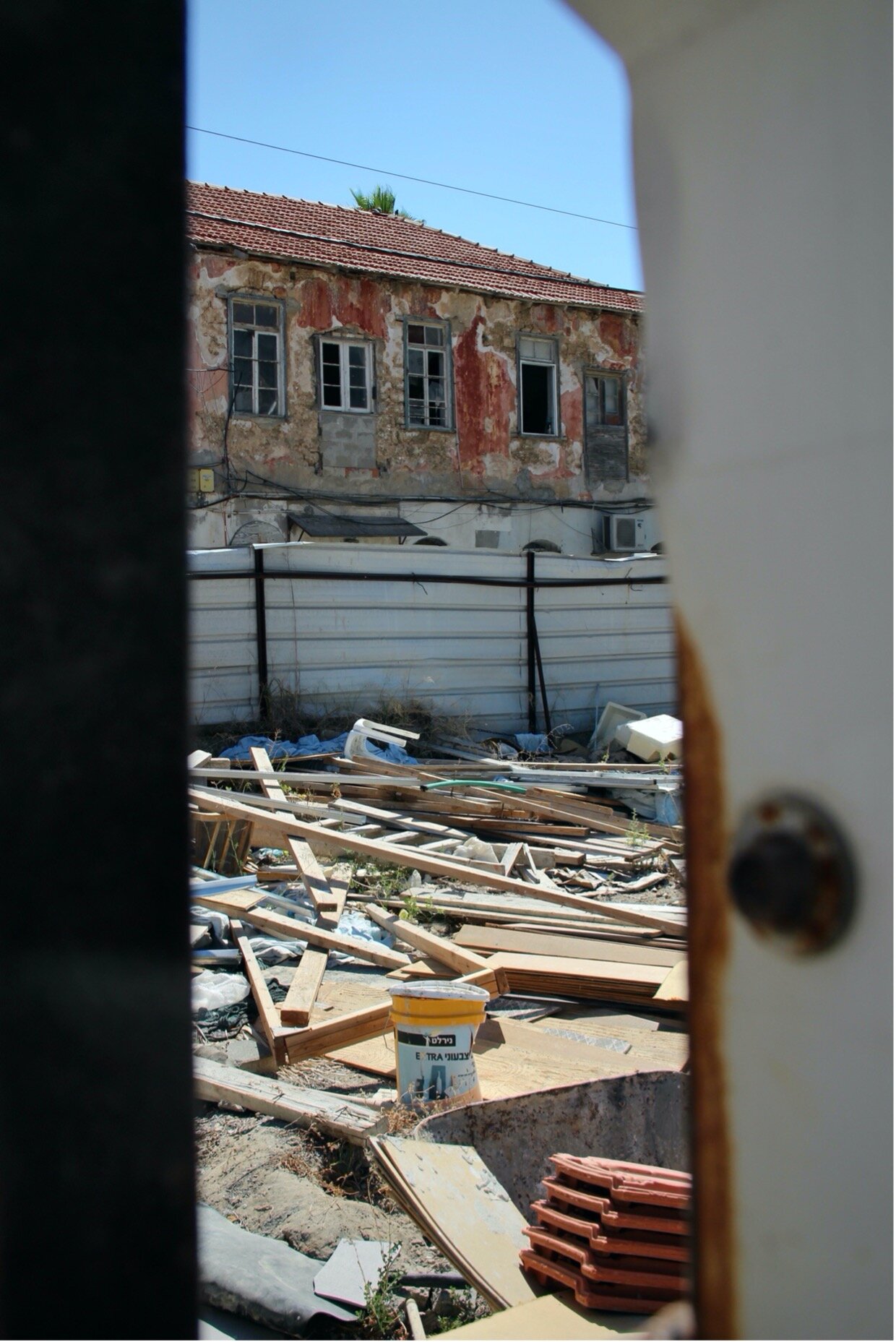

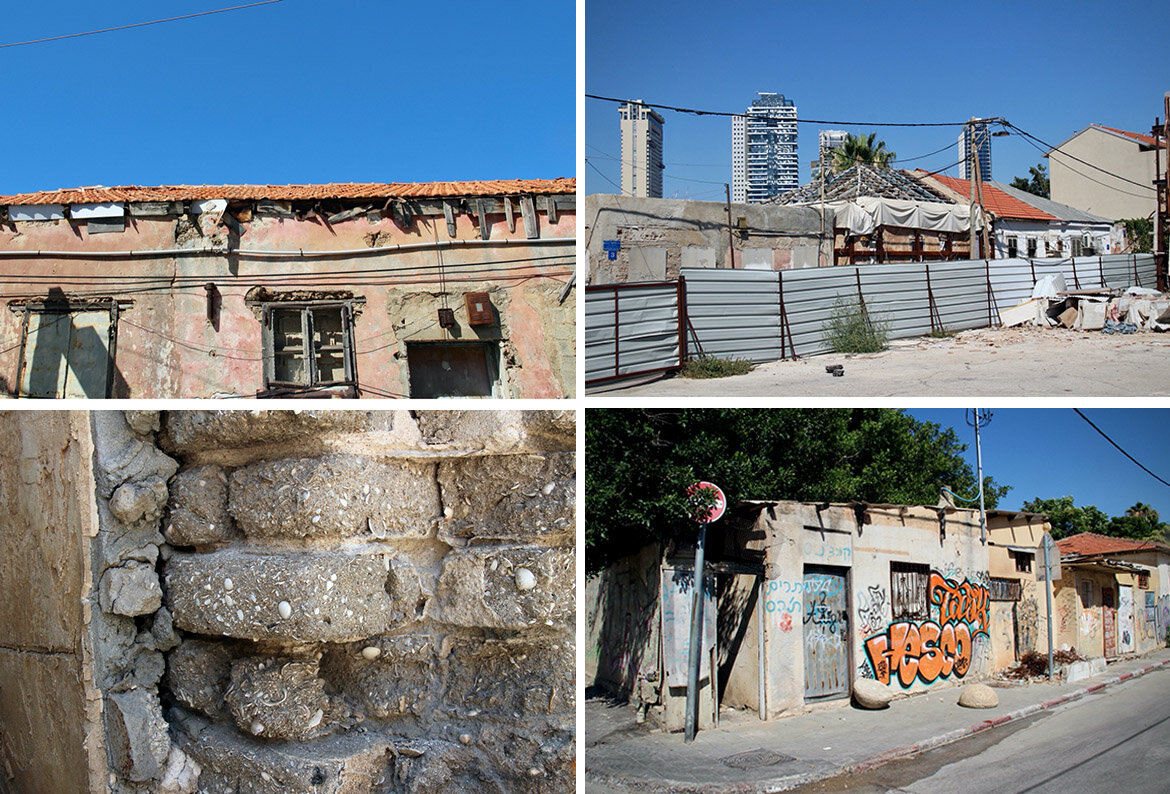

The preceding images are demonstrative of the colonial ethos in Tel Aviv architecture and the broader built environment. Not unlike the Etzel Museum across Kaufmann Street in Charles Clore Park, there is a perversion and manipulation of ruins, of traces of the past bespeaking the gentrification and commodification of site. The crumbling sandstone and Mediterranean seashells are mixed with shards of terracotta tiles and concrete. It is almost like archeology at eye-level, a presentation of palimpsest; bits and pieces of lives and livelihoods, skins of Jaffa oranges, the desire paths of Bedouin grazing their animals, the sweat of merchants and railway workers and salt of the sea — of possibility and openings, compressed into enclosure. Walls and new borders to separate communities, distinguish the Other, designate what’s worthy of mark-up and marketing and what is swept aside (Fig. 3.25 – 3.26).

As highlighted in these photographs, the structures and spaces which were imbued with charge — the Palestinian cultural and social content; the labor histories of various communities, economic triumphs and everyday operations in previous eras have been decanted from Neve Tzedek and its environs; the empty shell now refilled with the hubris of Zionist mythology and capitalist coercion. The materiality of the landscape and built environment is an eyewitness to past events and social interactions, as well as those of this very moment (Till, 2005). These photographs are attentive readings of the materiality of Neve Tzedek, revealing of the contemporary settler colonial organization of space and the concurrent capitalist deterritorialization and reterritorialization of territory (Deleuze et al., 2008), where “the removal of existing significations as a precursor to their redefinition [is] in terms more conducive to capital accumulation” (Leshem, 2013, p. 529). Presently stripped of virtually all signification of Palestinian identity, these sites are victim to the simultaneous hegemonic acts of erasure and reinscription.

The whitewashed walls and over-irrigated flora in this artscape are both flattening and encouraging of Otherness: “Being nothing other than style, [the culture industry] divulges style’s secret: obedience to the social hierarchy” (Adorno & Horkheimer, 2002, p. 104). While the conscious stylization of this urban space is intrinsic to the promotion of Neve Tzedek, and more widely Tel Aviv, I believe it is the banal moments in the built environment — oversights, indifferences, taken-for-granteds (taken-as-truths) — rendered more noticeable through practice-based data collection that aid in exposing how sociospatial segregation is continually reproduced and how an aesthetics of occupation, of violence against the land and its people, underlies the cultural infrastructures of the city.

Fig. 3.26.

This critical visual methodology, strengthened in part by the work of Rose (2001), is an approach “that thinks about the visual in terms of cultural significance, social practices and power relations in which it is embedded; and that means thinking about power relations that produce, are articulated through, and can be challenged by, ways of seeing and imaging” (p. 3). It is in these heavily mediated sites of cultural consumption that attuning to the fringes and fissures work toward dismantling hegemonic space. This is not only the case with documentation in and around The Station, but along Shabazi Street, the core boulevard for artscapes in Neve Tzedek which runs the length of the neighborhood.

A foundational cultural and spatial erasure inherent in this article begins with the obfuscated history of the neighborhood and the reinforcement of Tel Aviv as terra nullius before its boom. That Neve Tzedek sprung forth from empty sand; structures then deteriorated with the sea breeze, as development’s charge pushed north and east. But arts-led gentrification saved these sites: quaint, expensive, exclusive. The Mediterranean imaginary drifts effortlessly in and out of restaurants and grazes chipped stucco walls. Tiny galleries, boutiques and public artworks have culturally “recharged” Shabazi and Neve Tzedek as a whole, reintroducing its potential and then enticing urban dwellers, tourists and investors (Mommaas, 2004). Hawari et al. (2019) cut through the mirage:

The practices of presenting and marketing Israel to an international audience, whether in the academy or to the wider public, launder Israel’s past and present; hiding the violence of colonial disruptions and expulsions beneath articulations of moral legitimacy, national longing and belonging, and the right to claim sovereignty over territory, law and life in Palestine. These are then further buried beneath Israel’s global ‘brand’ of high tech and entrepreneurial prowess, of gay-friendly street parties in Tel Aviv, of a ‘diverse’, ‘complex’, ‘multicultural’, ‘democracy’ (but, ‘not without its problems’); a ‘station’ (as we read in Joseph Conrad’s work) capable of pacifying and connecting – or containing and securing – an unstable, undemocratic and deeply insecure Middle East, to the rest of the world. (p. 156)

Fig. 3.27.

Heritage, conservation and restoration are key themes in travel blogging about Neve Tzedek whose frequent if not glaring omissions contribute to the discursive and cultural erasures of the neighborhood and its history. While there aren’t brownstone structures in Neve Tzedek like in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, for example, the Eclectic, International Style and Bauhaus-inspired architectures, as well as other pre-Nakba vernacular structures are subject to similar interior renovations and façade facelifts. The market in this area simultaneously demands modern, upscale finishes and finesse alongside distinctly antiqued, unique touches. Portrayals of “the past” abutted with the “modern” present and promised future of the neighborhood, create new temporal categories for and understandings of this lived space all while whitewashing social problems and conflict from the spectacle of the city (Till, 2005).

Of course, this begs: Whose spaces are deemed worthy of preservation? Whose notions of the picturesque are reproduced and enshrined? An aggregation of symbols, metaphors, trends and materials commodified for upwardly socially mobile classes razed complex and contested political, economic and cultural elements in recent decades as this neighborhood gentrified. Hegemonic images, beliefs and whole lived social processes that are organized by dominant, power-wielding values and meanings are what’s collapsed into these notions of the picturesque, the bohemian (Williams, 1977). This cultural hegemony in Neve Tzedek and Tel Aviv more widely is by no means abstract or static; it is lived, it is — just like the occupation and colonization of Palestine as a whole — always ongoing. It does not exist as a passive form of dominance; Indigenous Palestinian culture is actively suffocated if not nearly entirely erased from the space. Examples of this include an absence of Arabic signage and Palestinian cultural centers; demographic control of the neighborhood (including business ownership, the hotel industry and its clientele, renters and property owners), the representation and attribution of literature, architecture, cuisine, music, and so on. It perverts itself into all aspects of society, of the built environment — in multiple dimensions.

Fig. 28.

This lived hegemony must be continually renewed, recreated, defended, and modified in order to retain relevance and maintain political, religious and cultural control. In this regard, Tel Aviv — with ongoing reinvention and redevelopment of neighborhoods like Neve Tzedek — is a predatory city. This predation takes many forms but can be observed in my documentation of various structures along Shabazi Street and in nearby corners. While the gentrification of portions of the neighborhood crafted a new visual regime of tidiness, luxury and cool, there remains structures, plots and other spaces that are intentionally blighted, or construction projects paused before completion — sites of annexation and occupation that curtail public use or counter-hegemonic opportunities. My documentation of some of these structures and spaces proves demonstrative of politically motivated preservation and redevelopment in the neighborhood — a constellation of factors and stakeholders determine what is worthy of conservation, and what deserves to be bulldozed (as well as what remains in-limbo, and how). While any city has its share of failed projects and investments going belly-up, there is a high concentration of purposeful disrepair (in the hands of the municipality, private investors, community members and the like) that at once retains the “edginess” of the neighborhood, hoards land for bigger/more prolific investment and impedes social and cultural progress at various scales (Fig. 3.27 – 3.39).

In place promotion of Neve Tzedek, the materiality of the built environment is fetishized and anthropomorphized for its charm and artistic energy. Idealized vignettes of Mediterranean bliss along Shabazi Street and adjacent pockets are sought out by Tel Avivians and travelers alike. The visuality and materiality of this neighborhood and others throughout Tel Aviv serve a propagandistic function to encourage tourism and enterprise and further balloon property values. This curated image of a tortuously trendy space sets the borders of who and what does or does not belong; continually reproducing sociospatial segregation in the city.

Figures 29, 30, 32 & 33. Figures 3.34, 3.35, 3.36 & Figure 3.37 — An urban emulation of dendrochronology (2018). Figures 3.38 & 3.39.

References

Adorno, T. W., & Horkheimer, M. (2002). Dialectic of enlightenment: Philosophical fragments. Stanford University Press.

Dance, J. (2019, June 25). Why is Jerusalem blurry on Google Maps?

Deleuze, G., Massumi, B., & Guattari, F. (2008). A thousand plateaus capitalism and schizophrenia. Continuum.

Hawari, Y., Plonski S., & Weizman, E. (2019). Seeing Israel through Palestine: Knowledge production as anti-colonial praxis. Settler Colonial Studies, 9(1), 155-75.

Kearns, G., & Philo, C. (1993). Selling places: The city as cultural capital, past and present. Pergamon Press.

Leshem, N. (2013). Repopulating the emptiness: A spatial critique of ruination in Israel/Palestine. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31(3), 522-537.

Mommaas, H. (2004). Cultural clusters and the post-industrial city: Towards the remapping of urban cultural policy. Urban Studies, 41(3), 507-532.

Rose, G. (2001). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Roṭbard, S. (2015). White city, black city: Architecture and war in Tel Aviv and Jaffa. Pluto Press.

Till, K. (2005). The new Berlin. University of Minnesota Press.

Williams, R. (1977). Marxism and literature. Oxford University Press.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)