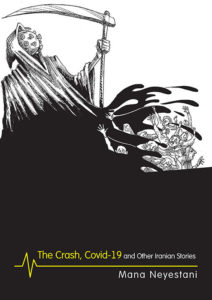

From the Balfour Declaration to the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement for the post-WWI division of much of the Middle East, to the CIA-MI6 fomented coup against Iran’s Mohammad Mossadegh, Western countries have their share of responsibility for the political upheaval that has shaken the region for over a century. Dina Rezk reviews the new study from London School of Economics professor Fawaz A. Gerges.

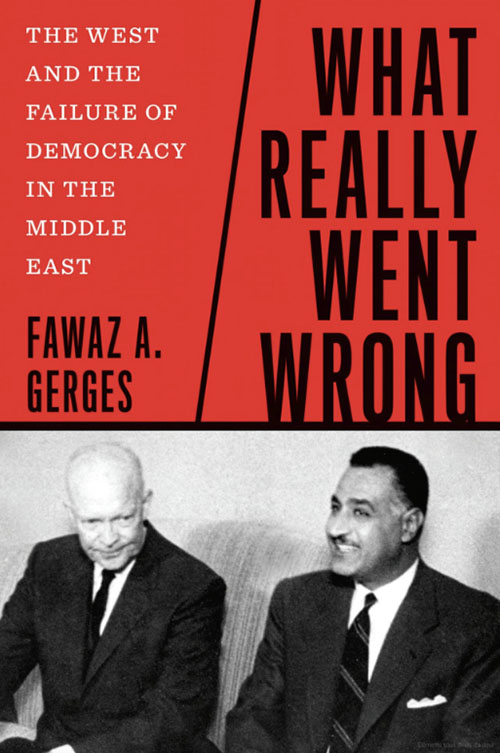

What Really Went Wrong, The West and the Failure of Democracy in the Middle East, by Fawaz A. Gerges

Yale University Press 2024

ISBN 9780300259575

What might have been? This is the central question animating Fawaz Gerges’s What Really Went Wrong: The West and the Failure of Democracy in the Middle East. The book is a rich, ambitious, and timely exploration of the role Western meddling has played in the region’s ongoing crises, but also a speculative argument as to how the modern Middle East might have evolved had the United States used its power to support postcolonial leaders rather than undermine them. The history is sound and the speculation intriguing, if not quite original. All in all, the Lebanese American Gerges, a professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science and the author of several books, raises provocative questions about the opportunities as well as the limits of counterfactual “what ifs” as drivers of intellectual inquiry. The author’s goal is to “engender a debate about the past that can make us see the present differently.” That debate is sorely needed.

The book takes its title from, and serves as a deliberate riposte to, Bernard Lewis’s controversial post-9/11 What Went Wrong: The Clash Between Islam and Modernity (2002). No doubt it also has its eye on Samuel Huntington’s earlier The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996, expanded by the author from his 1993 Foreign Affairs article of the same name). Lewis, Huntington and others have accounted for the ills of the Middle East largely in terms of, as Gerges puts it, “ancient hatreds, religious differences, or some chaos inherent to the region.” The reality is much different. “Far from being caused by some mystifying ‘oriental’ (or even ‘Abrahamic’) tendency toward entropy,” Gerges explains, “the simple fact is that greed, arrogance, and a thirst for power and control of the region’s resources are mainly to blame. And the clear lesson is that far from achieving any material gain, status, or influence, these drivers only lead to costs: in human progress, prosperity, peace, and life.”

The author makes two central arguments. The first is that “against great odds, the people of the Middle East have consistently and persistently struggled to attain freedom and dignity.” Nowhere is this more readily apparent, he stresses, than in Egypt and Iran. For this reason, he devotes much of the book to these two countries, and to popular nationalist leaders Gamal Abdel Nasser and Mohammad Mossadegh, both of whom took the reins of power in the early 1950s, in Egypt and Iran respectively. (Unlike Nasser, who would assume the presidency and rule Egypt until his death a decade and a half later, Mossadegh would not remain in his position of prime minister for long.) The second argument Gerges makes is that “the countries of the Middle East have not been able to chart their own course because of factors such as imperialism, the West’s coveting of the region’s petroleum, the global Cold War, and interrelated geostrategic rivalries and conflicts.” This places his book firmly within a wider literature that has demonstrated that Europe was by no means the principal battleground of the Cold War and that colonialism endured well beyond the formal “end of empire.”

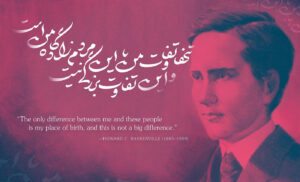

The author takes us through rich reconstructions of the anticolonial movements in Iran and Egypt, offering colorful biographical accounts of Mossadegh and Nasser. Much of the material on the latter is borrowed from Gerges’s own Making the Arab World: Nasser, Qutb, and the Clash that Shaped the Middle East (2018). Less familiar to some readers will be the material on Mossadegh, who is described by the author as “one of the most dramatic and unorthodox politicians that Iran has ever known.” We learn, for example, that Mossadegh often wept publicly. Whereas such outpourings of emotion were ridiculed by his international enemies, they were celebrated in Iran and contributed to the nationalist politician’s popularity. More importantly, we are reminded of the Cold War origins of Iran’s much-debated current nuclear program and the role of the United States in launching it as part of President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” initiative in 1957. This was a bargaining tool the US deployed in dealing with certain developing countries, in which the superpower agreed to provide research reactors, fuel, and training for civilian nuclear programs in exchange for a commitment that the technology and education provided would be used only for peaceful purposes. To that end, the US supplied Iran with weapons-grade uranium and, later, helped it build a nuclear reactor. The collaborative nuclear relationship lasted until the revolution in 1979. This is the kind of historical detail that rarely finds its way into mainstream Western media narratives of Iranian nuclear ambitions — despite being, as Gerges points out, “an astonishing fact to contemplate from today’s perspective on the Iran nuclear issue, which is widely perceived to trace its origins to clerics seeking the game-changing weapon in 1988 at the end of the Iran-Iraq war.”

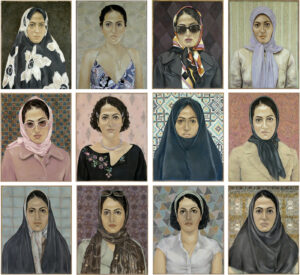

Gerges suggests, as others have before him, that the 1953 US and UK-backed coup that removed Mossadegh and re-installed the unpopular shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, caused “deep psychological trauma at the core of Iranian society.” The subsequent suppression of the (largely secular nationalist) opposition, the creation of the notoriously ruthless SAVAK secret police to monitor and intimidate the population, and the granting of favorable oil concessions to the US generated grievances that would be weaponized by Iran’s mullahs in the 1979 revolution. In re-examining the covert operation that ousted Mossadegh, Gerges makes tantalizing reference to “thousands of critical new documents” recently declassified in both the US and Iran. I would have liked to see more of the Iranian perspective of these events and therefore more references to Iranian sources. In an endnote, Gerges points out that young Iranians are moving away from the belief that the US is the root of all their country’s afflictions, but I found myself reflecting on this shift, particularly in light of the fact that, as mentioned, US meddling in Iran caused long-lasting collective trauma. How has Western intervention been understood by Iranian people and how has it affected their lived experience? Scholars have begun to explore the differing and evolving vantage points through, for example, the Iranian Oral History Project at Harvard University, but much of what we know about US intervention in Iran still comes through the lens of Washington.

Subsequent chapters on Egypt similarly explore what might have happened had US policymakers embraced Nasser rather than regard him as a threat to American power. Gerges rightly notes a divide between, on the one hand, the hawks in Washington (in particular the infamous Dulles brothers, Secretary of State John Foster and CIA director Allen), and, on the other, diplomats on the ground such as US ambassador to Egypt Henry Byroade. The Dulles brothers and their ilk favored cutting Nasser down to size, whereas Byroade and those of similar inclination sought to challenge the “prevailing imperial mindset.” In fact, Byroade’s diplomatic cables to his superiors during his tenure as ambassador in the critical years 1955-1956 show “why Washington’s informal empire builders lost Egypt in the mid-1950s and turned Nasser from a potential friend to a bitter foe.”

At times, Gerges’s narrative is lacking in detail. When it comes to the already much-explored Suez Crisis, which culminated in the Tripartite Invasion of Egypt by the UK, France, and Israel in 1956, Gerges summarizes American opposition to this outbreak of Western-Israeli adventurism as “fear of losing control of Middle Eastern oil.” That was a factor, to be sure, but the author neglects to mention the Soviet invasion of Hungary within days of the Suez Crisis’s eruption. Had the US, which condemned the invasion of Hungary, failed to do the same with regard to the invasion of Egypt, it would have left itself vulnerable to accusations of hypocrisy, all the more so for styling itself the leader of the free world. Another lacuna is that Gerges does not explore the effect the assassination of John F. Kennedy had on the more promising and productive relationship the American president had with Nasser. What if Kennedy had lived? Might we have seen a different Middle East policy emerge from the White House?

The June War (also known as the Six-Day War) of 1967 was a prime example of the importance of personalities and presidential leadership in shaping US relations with the Arab world. Scholars have long debated whether the superpower gave Israel a “green light” for the surprise attack on its neighbors, including Egypt, that so changed the political landscape and map of the contemporary Middle East. Yet even though the war came to constitute a profound turning point in how US power was perceived in the region, we are provided with little information about precisely how Nasser “sleepwalked” into it. Similarly, we are told, but not shown, that “[i]f the United States had been a friend of both Egypt and Israel, the Six-Day War in June 1967 could have been prevented through robust diplomacy because Washington wouldn’t allow two allies to go to war against each other.”

Of course, these macro-level relationships matter, but there were also important regional dynamics at play. It is for example equally plausible that had Syria not accused Nasser of “hiding behind the skirts” of the UN in justifying his non-intervention whenever Syrian territory was attacked by Israel, the Egyptian leader, smarting from a stalemate in the Yemeni civil war (which came to be considered “Egypt’s Vietnam”), might not have felt the need to request the removal of UN forces stationed in the Sinai Peninsula to separate the Egyptian and Israeli militaries. Similarly, he might not have closed the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping. Israel’s response was to initiate the June War, which quickly overwhelmed Egypt and its neighbors.

Otherwise, however, the author does well to draw on his interviews with former Egyptian officials, which bring to the fore the impulsive nature of Nasser’s decision-making in the crisis. This leadership trait played out in Egypt’s foreign policy, including the short-lived union with Syria, the Yemeni conflict between Egypt-backed republicans and Saudi-supported royalists, and of course the June War with Israel, oftentimes with tragic consequences. Nasser’s impulsiveness notwithstanding, there was another, larger factor at work, one that Gerges for the most part succeeds in capturing. “[T]he American government,” he observes, “never wanted to understand Egypt on Egyptian terms. With open eyes, the Cold War advocates could have easily forestalled Nasser’s turn to communist Russia for aid and arms, and the United States would not have become a nemesis across the Middle East.” His analysis supports my own scholarly findings and those of other historians who have argued that there was a discernible school of thought within the US “official mind” that saw the benefits of a pro-Nasser policy. Tragically, this failed to find its way into policy-making circles.

What is the upshot of all this? “Translated into modern terms,” writes Gerges, “the message is clear: it is not too late to embrace the countries and peoples of the Middle East as equals and respect their choices and aspirations and open the path to productive collaboration.” Here I found myself — once more — hungry for details: what might this look like in practice, and what do we do with this alternative view of the past? Gerges stops short of suggesting, for example, that reckoning with the history of the US-Iranian nuclear relationship might mean understanding and accepting Iran’s desire to have a viable nuclear program. I realize why he might be loath to translate his general argument into more concrete policy recommendations in today’s highly polarized political climate; arguably, it is not his job as a scholar to do so. Still, he is well-placed to speak truth to power in actionable terms. The important work of NGOs, such as DAWN, that support democracy and human rights in the Middle East and North Africa, is just one example of how civil society can take the lead in challenging Orientalist stereotypes about the region and “promoting new solutions” to long-standing problems. As Palestinians face an ongoing genocide in Gaza, with little support from Arab states, DAWN’s work advocating legislation that limits arms transfers to repressive regimes, and its spotlighting of US-based lobbyists paid to keep support flowing to illegitimate governments, go some way towards rectifying the past and present injustice of US foreign policy in the region.

Overall, I enjoyed the book because I think that, too often, historians do not consciously allow “what if” questions to inform their interrogations of the past. What Really Went Wrong raises important questions about whether, how, and why we engage in counterfactual history — in other words, “what if” speculation. Richard Ned Lebow has persuasively argued that “the difference between so-called factual and counterfactual arguments is greatly exaggerated; it is one of degree, not of kind.” Gerges is at his best when weaving painstaking argument, historical detail, and thoughtful questions into compelling narrative cloth. His examination, though repetitive at times and lacking specificity in places, seeks to drive home an important and generally convincing argument: those in the highest echelons of power in the US failed to capitalize on the postcolonial past they shared with nations seeking independence and autonomy. Instead of viewing the states of the Middle East as equals with which it could collaborate, the US sought to dominate them, with ultimately tragic consequences that remain with us to this day.

I was a 22 year old UNA Midwifery Volunteer in Amman, post the catastrophic 6-DAY WAR. Awed by how political the middle class level educated doctors and their friends were. Kamal Nasser being a close friend of my doctor boss. Arriving one day from prison, serving time as they all seemed to have done. For their Ba’athist beliefs. One even said to me: “Is it our fault that we don’t know how to fight!” They joked about everything……I could not imagine any Brits going to prison for their political beliefs….But my Irish relatives had done so. Queen Nour, I believe, wrote that Nasser & Assad plotted & planned secretly for the 6-Day War. Only inviting King Hussein to a meeting, the night before it all kicked off. Which allegedly caused him great despair as he knew the outcome. What on earth were they thinking? As the Palestinians and Israelis seemingly jogged along in a far more harmonious state, than they do today! As did Jews and Arabs in other ME countries. Ya haram!