The actor and filmmaker died at the age of seventy-two, leaving behind a body of work that represents dignified resistance through art.

The passing of iconic Palestinian actor and filmmaker Mohammad Bakri marks not only a melancholy milestone but also the end of an era. The 72-year-old Bakri, who was born in the village of Al-Bi’ina in the Galilee in 1953, personified Palestinians in all their struggles and triumphs. His life and his roles unfolded as a powerful kind of metatheatre, elevating him to the status of a national hero and a symbol of cultural resistance.

From the young man who charms his Jewish lawyer and makes her confront the legacy of the Holocaust and the reality of occupation in Costa-Gavras’ 1983 film Hanna K, to the political prisoner who teams up with a Mizrahi thief in the 1994 Academy Award-nominated film Beyond the Walls, to the Palestinian everyman he portrayed in one-man plays like 1986’s The Pessoptimist (adapted from Emile Habibi’s novel The Secret Life of Saeed: The Ill-Fated Pessoptimist); and his 1993 performance in a Palestinian version of the classic novel about post-colonial identity by Sudanese writer Tayib Saleh, Season of Migration to the North, through to 1999’s Abu Marmar performed in Hebrew and Arabic, Bakri’s roles epitomized the Palestinian struggle. But they also doggedly explored the themes of cross colonial cultural hybridity and the strange gestalt of the Israeli/Palestinian experience.

And it is this that his friends and fans in Israel/Palestine mourn as well as his passing. Bakri, fluent in Arabic and Hebrew, cut his dramatic teeth with both Habima Theatre in Tel Aviv and al-Kasaba Theatre in Ramallah. He was a fervent believer in the necessity of coexistence. It was a belief that never faltered, even as he was persecuted by the Israeli state after making his groundbreaking and award-winning 2002 documentary Jenin Jenin, deemed (after the complaints of a handful of offended reservists who participated in the Jenin refugee camp massacre) by the Israeli Supreme Court to have been made with “improper motives.”

And Bakri clung to hope even in the midst of ongoing genocide. While the Palestinian dream has turned nightmarish, it has found new life in the midst of horrors. Sadly, the spirit of coexistence has been mortally wounded by an increasingly rightwing government that no longer pretends to believe past platitudes.

As Bakri’s friend Gideon Levy wrote in Haaretz, he was the only Israeli who attended Bakri’s funeral. Meanwhile Bakri had told Levy he was planning to attend the funeral of Israeli director Ram Loevy only a few weeks before his own death.

Now, as Levy noted, “Bakri is dead, the Jenin camp is destroyed and all its residents have been expelled, homeless once more in another war crime. And hope still beat in Bakri’s heart, until his death; we did not agree about it.”

When I first met Bakri in Jerusalem in 1994, at the height of hope for peaceful co-existence, the 41-year-old actor was in his prime, moving with a kind of feline grace and embodying an acting style that came from a heady combination of well-honed craft and gut instinct. These were the days of aspiration (or perhaps fervent longing?) for a new reality, post Oslo accord and before the assassination of Rabin. I was writing for the first joint Israeli-Palestinian monthly magazine in English (called rather vaingloriously The New Middle East, and published by Palestinian Hanna Signora) about troupes like al Hakawati Theatre, at a time when the power of theatre as a vehicle for social change and the idea of peace in our time were more than mere clichés. When we met again, it was in 2016 at the Carthage Film Festival, where Bakri was being honored for his contribution to cinema. He still had that gravitas and grace, but the toll of enduring Israeli lawsuits and death threats had taken a toll on his mental and physical health.

In retrospect, Bakri’s work was both pioneering and sadly prescient.

He wrote in an op-ed in Haaretz that same year, on the ordeal he endured after the release of Jenin Jenin, “In my film, I tried to give a platform to the camp residents who had no voice. I didn’t know I would spend the next fourteen years defending myself in court, my family from death threats and my reputation from an ongoing media and political lynching.”

In the same op-ed he went on, “I never pretended to be a director of documentary films. That’s not my field. I’m just an actor. I didn’t choose to direct documentaries, but sometimes you find yourself in certain situations where reality impels you, and your human dignity obliges you, to respond.”

He said that his first documentary 1948, produced in 1998, on the 50th anniversary of Israel’s founding, was a response to a TV series on Israel’s Channel one called Tekuma, told exclusively from the Israeli side.

Similarly, he wrote that he went into the Jenin refugee camp to “bring out the other truth that wasn’t being told in the Israeli media or on the television news. I tried to give expression to the outcry of the people in the camp who have lived for decades under Israeli occupation, who endured a massive military offensive involving thousands of soldiers with tanks, artillery, planes, and bulldozers that destroyed large parts of the camp.”

In retrospect, Bakri’s work was both pioneering and sadly prescient. The actor, who stayed politically active until the end, working with young Israeli activists in the Joint List party — a political alliance of Arab majority parties in Israel that sought to increase Arab representation in the Knesset but dissolved in 2022 — inspired a whole new generation of actors and filmmakers.

While Bakri worked with veteran directors like Michel Khleifi, starring in the 1994 film A Tale of Three Jewels (the first film to be shot entirely in the Gaza Strip), he also starred in Najwa Najjar’s 2005 film Jasmine’s Song. Najjar remembers their collaboration with great affection and respect, telling TMR, “Mohamed Bakri was a giant of Palestinian cinema and theatre. Through his presence on stage and screen, he gave voice to our stories, our struggles, and our humanity. As a filmmaker, I was inspired by his courage, generosity, and unwavering commitment to truth—he showed us what it means to create art that resists, remembers, and endures.”

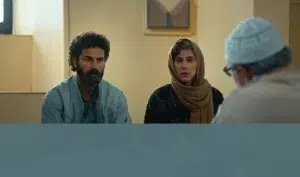

He also starred in Annemarie Jacir’s 2017 film Wajib — a comedy/drama – father/son travelogue through a town in Nazareth. Jacir was the first to cast Bakri and his actor son Saleh together in lead roles. As Jacir told TMR, “After years of working separately and making names for themselves, I cast Mohammad and Saleh in their first film together with lead roles. It was a magical collaboration. Wajib was their first real film together and it was incredibly powerful for me. We worked very well together. I will never forget our work on Wajib. He did everything with passion and love.”

Bakri’s influence reached across continents to inspire Canadian indigenous artist Wanda Nanibush, who was fired from the Art Gallery of Ontario for her pro-Palestinian views and who organized screenings of Jenin Jenin in Toronto when it first came out, in spite of protests by pro-Israel organizations

“Bakri’s work inspired me to think about the connections between settler colonialism and its methods and our many resistances,” she told TMR, “filmmaking being one of the best forms of both informing, imagining, and visioning freedom.”

The Jenin Freedom Theatre issued a statement following Bakri’s death, noting:

Mohammad Bakri had a very special connection with The Freedom Theatre in Jenin, a theatre founded by the late Juliano Mer Khamis, with whom he shared a deep friendship and mutual respect. He was a loyal supporter of the artists there, participated in the film In A Thousand Silences, produced by TFT as part of The Revolution’s Promise project in collaboration with partners, and was in close discussions to join the artistic committee for the upcoming production The Martyrs Return to Ramallah by Walid Daqqa, confirming his role as both observer and storyteller of Palestinian identity on the stage.

Bakri’s last film, the critically acclaimed All That’s Left of You directed by Cherien Dabis, starred Bakri and his two sons, Adam and Saleh. The moving tale of seventy-five years of intergenerational Palestinian trauma cast Bakri as a grandfather who survived the Nakba and was filmed during the genocide in Gaza. It was perhaps the perfect role for the actor whose career spanned the Palestinian experience, both embracing and transcending identity.

As Dabis posted on her social media on the day of Bakri’s death:

This loss hurts in ways that are hard to articulate. Mohammad’s passion for cinema was inseparable from his unwavering commitment to a free Palestine. He understood art as resistance, as memory, as testimony. He carried our stories with dignity and ferocity, even when the cost was enormous. And it was.

Mohammad, your contribution to cinema and to Palestinian liberation cannot be overstated. You gave us language, presence, and moral clarity. Your legacy lives not only in the films you made, but in the countless artists you shaped, inspired, and emboldened, including your beautiful, brilliant children, who carry forward your passion for a free Palestine.

For many cinemagoers who appreciate film from the Arab world, Mohammad Bakri, like his compeer Hiam Abbass, has represented the best of Palestinian culture and cultural resistance, of sumūd in the face of decades of adversity under Israeli occupation. While Bakri has passed the baton to his sons Saleh and Adam, his place in the history of Palestinian theatre-making and cinema is secure.

When I think of Bakri’s legacy now, I remember the poignant scene in Hanna K in which his character rides in the back of an IDF jeep towards deportation via the Allenby Bridge, his eyes scanning his beloved homeland with a deep longing and a farewell gaze. A soldier escorts him to the bridge and then tells him, “You are free now.”

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)