Select Other Languages French.

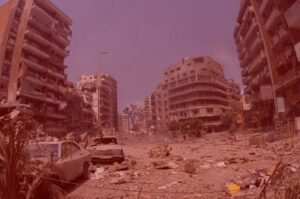

As more than a million Palestinians in Gaza remain displaced, cold, without shelter, and waiting for aid, Big Tech continues its campaign of digital erasure.

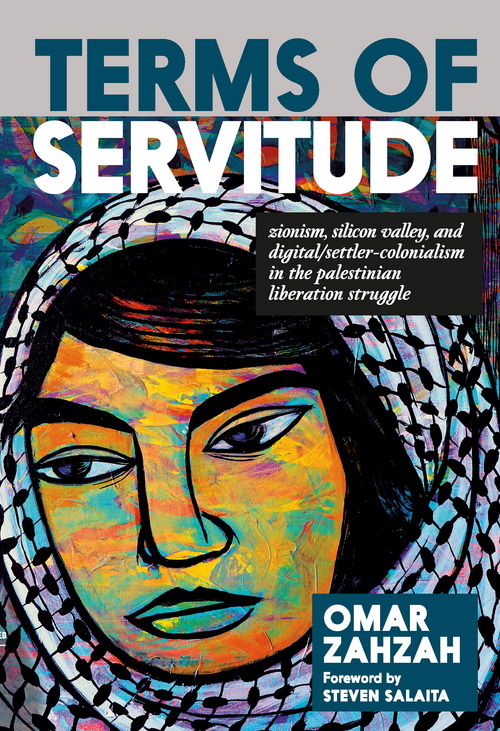

Terms of Servitude: Zionism, Silicon Valley, and Digital Settler Colonialism in the Palestinian Liberation Struggle, by Omar Zahzah

Seven Stories Press 2025

ISBN 9781644214800

On October 12th, 2025, one week after the most recent “ceasefire” agreement, even as Israel continued its genocidal bombardment of Gaza, I logged on to X and saw the news of the assassination of Saleh Al-Jafarawi at the hands of an Israeli-linked gang. The 28-year-old Palestinian journalist’s videos, photographs, and stories regularly went viral, helping to globally transmit news of Israel’s genocide in Gaza, despite the multiple forms of silencing and use of Israeli propaganda, otherwise known as hasbara. Al-Jafarawi had previously received numerous threats from the Zionist military. His murder makes him one of more than 270 Palestinian journalists in Gaza targeted and assassinated by the Israeli state. In January 2025, he told Al Jazeera, “Honestly, I lived in fear for every second, especially after hearing what the Israeli occupation was saying about me. I was living life second to second, not knowing what the next second would bring.”

Imagine a Venn diagram whose two spheres are digital colonialism and settler colonialism. Digital settler colonialism is the area formed where the two overlap.

The next day, Drop Site News reported that, just hours after his assassination, Meta began quietly deleting all of Al-Jafarawi’s posts from their platforms. This was merely an acceleration of their censoring Al-Jafarawi. On March 9th, 2025, The New Arab reported that Al-Jafarawi’s two Instagram accounts, with a combined total of 9.5 million followers, had been “suspended indefinitely.” A few days after the news broke of Meta’s egregious acts of censorship, the writer and scholar Omar Zahzah, writing for The Palestine Chronicle, headlined an article, “Meta’s Deletion of Saleh al-Jafarawi’s Instagram Account is Digital Settler Colonialism in Action.”

At the time of Al-Jafarawi’s murder, I was reading Zahzah’s excellent and necessary new book, Terms of Servitude: Zionism, Silicon Valley, and Digital Settler Colonialism in the Palestinian Liberation Struggle. Throughout, Zahzah defines digital settler colonialism as capturing “the convergence of U.S. Big Tech digital colonialism and Israeli settler colonialism.” He explains: “My application of the term foregrounds the aggregate nature of the material conditions opposing Palestinian digital sovereignty. Imagine a Venn diagram whose two spheres are digital colonialism and settler colonialism. Digital settler colonialism is the area formed where the two overlap.” The example of Meta’s erasure of Al-Jafarawi hours after his death is a case in point, but Zahzeh goes beyond the usual suspects of social media giants Meta and X to include the use of AI technology by Big Tech companies such as Amazon and Google (including Project Nimbus, Where’s Daddy, and Lavender) and online doxing campaigns such as Canary Mission, JewBelong, and StopAntiSemitism (to name just a few of Zahzah’s case studies).

Like millions around the world, I mourned Al-Jafarawi’s murder and joined in with a global condemnation of the tech giant Meta for erasing his archive. These public and hyper-visible acts of digital settler colonial erasure are entwined with thousands of personal attacks, as Meta and X, by weaponizing their “terms of service,” are constantly policing the platforms of Palestinians in Gaza, the occupied West Bank, and the diaspora, as well surveilling their anti-Zionist allies around the world.

A week after Al-Jafarawi’s murder, I once again logged on to X to share the GoFundMe and Chuffed campaigns of friends in Gaza, who were still displaced, cold, without shelter, and waiting for promised aid. One friend, who usually sent me daily DMs with the language she wanted me to use in my posts that day, had gone strangely silent. When I checked for updates on her X page, I received this warning: “Caution: This account is temporarily restricted. You’re seeing this warning because there has been some unusual activity from this account. Do you want to view it?”

I clicked continue but noticed that she hadn’t posted anything in three days, which was highly unusual. I sent her a message on Instagram and waited. When she finally logged on and responded, she told me that she had been restricted by X for days. Because this was the main site where she shared her own GoFundMe page, her campaign had stalled and she hadn’t received any donations since she lost access to her account. She was in a panic and didn’t know why her account was restricted. Equally, she didn’t understand why it was reinstated several days later. This story is ubiquitous in Palestine-related online spaces; “digital settler colonialism” gives us the necessary language to capture the multitude of ways these tech platforms help facilitate Israel’s genocide through their treatment of Palestinians online. Critically, Zahzah reminds us, “It is not up to Meta[1] to normalize Palestinian oppression, or dictate how Palestinians should relate to their colonizer.” And yet, these platforms have become extensions of such violent interests.

For those of us involved in organizing, mutual aid work, and knowledge production and consumption connected to the Palestinian liberation struggle, these social media platforms are ambivalent spaces. Like so many others, I rely on these platforms for information, advocacy, connection, and information. Instagram, WhatsApp, and X are how I stay connected to friends in Gaza and — similarly — these platforms are some of the most critical spaces through which people in Gaza stay connected to each other and the rest of the world. These digital spaces have been crucial for mutual aid collectives like The Sameer Project and Lifeline4Gaza, as well as individuals with GoFundMe and Chuffed campaigns, to raise money in order to keep individuals, families, and communities alive. Such platform usage is not without its complications, as this has also created a world where people living through a genocide are forced to become social media influencers and dystopic reality television survivors, as one’s survival becomes directly connected to how well someone can monetize tragedies and backstories. Parents struggling to keep their children alive must simultaneously post and repost their needs in ways that will captivate the attention of those in the West. That is, if they’re lucky enough to have a phone, computer, tablet, and eSim. Additionally, as Ramzy Baroud argues (quoted by Zahzah), “Palestinians in Gaza use these platforms to communicate with one another, to know who is dead and who is alive, and to raise awareness of certain massacres often taking place in isolation, especially in the northern Gaza Strip.” In both of these cases, Big Tech has created a perverse paradox in which the users who rely on their technology for survival are also those who indirectly generate profits that these companies then use to give cover for genocide. As Zahzah shows throughout his book, these companies have the blood of tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of Palestinians on their hands.

I am writing this on day 785 of Israel’s genocide of Palestinians in Gaza. It is possible that between 700,000 and one million Palestinians in Gaza have been killed by Israel[2] and now, as winter comes to Gaza, more than a million people are left without adequate food, water, shelter, electricity, medication, warm clothes, and ways to sustain themselves and rebuild their lives. Lives that those of us in the West have been complicit in destroying through our tax dollars, our “both sides” fallacies, our patterns of consumption, and our silence.

Optimism is hard to come by now, more than two years into a livestreamed genocide. However, Omar Zahzah offers a sliver of hope in the book’s afterward, writing:

Working on this book has made me more critical of Big Tech, and more optimistic about the capabilities of activists and organizers. Individual creativity and resourcefulness drive counter-hegemonic uses of digital media. It is people, not platforms, that secure freedom. Palestine is no exception.

Just as organizations like the Hind Rajab Foundation are the result of individual creativity and resourcefulness in the face of so many state actors that have failed to hold war criminals accountable for their crimes, there must be a reckoning with and a rejection of Big Tech. This requires a decentralization of the internet through anarchist approaches to autonomous collectives and communities working outside the logics of capitalism, carcerality, and exclusion, revealed so starkly throughout Zahzah’s book. This work is being modeled through the research and organizing work undertaken by collectives like the Surveillance Resistance Lab. Such work reveals how the digital settler colonial frameworks of Big Tech rely on centralized capitalist consumerism, environmental degradation, and political hierarchies, which are inevitably spaces of surveillance, violence, and dispossession. Zahzah’s book reminds us that there is a world beyond these digital borders. By envisioning, building, and sustaining a decentralized world based on creativity, possibility, and liberation, we can move towards a decolonial digital horizon.

[1] Or any tech platform.

[2] According to statistical models published by The Lancet, it is possible that as many as a million Palestinians in Gaza have been killed by Israel. In July 2025, a study in Arena Online put the number of deaths closer to 700,000, which would also be much higher now.