Yasmine Motawy interviews Leila Aboulela on her creative process, writing while Muslim, and telling Sudan’s history through literature.

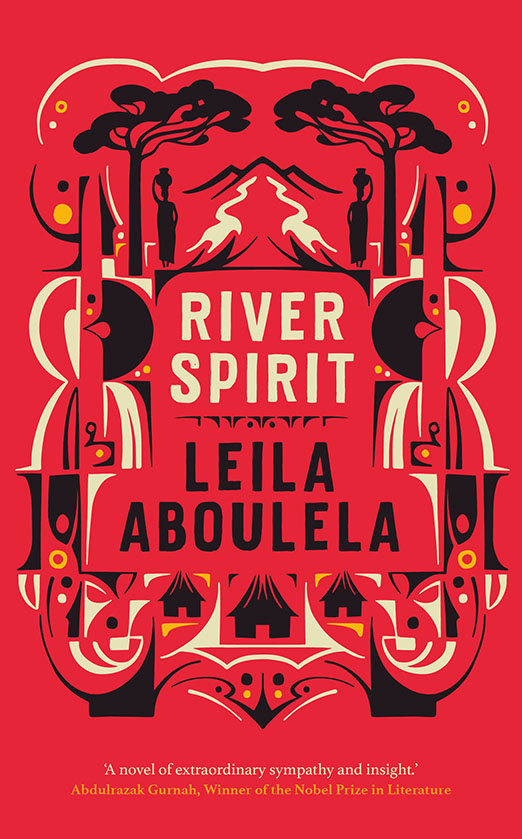

Leila Aboulela is an award-winning Sudanese author of six novels and two short story collections. She grew up in Khartoum, Sudan, and moved to Aberdeen, Scotland in her 20s. Her novels include the newly released River Spirit from Saqi Books in London, along with Bird Summons, Minaret, The Translator — a New York Times 100 Notable Book of the Year — The Kindness of Enemies, and Lyrics Alley, Fiction Winner of the Scottish Book Awards. Aboulela is also the first winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing. Her critically acclaimed work has been translated from English into 15 languages.

Yasmine Motawy: What is your creative writing process? I know that you changed the historical period you were planning to focus on in River Spirit (2023) following collegial interactions you had at the Bellagio Center residency, where you began the novel, and that you “found” one of the main characters in the Durham University archives.

Leila Aboulela: The Rockefeller residency in Bellagio was a unique experience because when I went there, I was at the very beginning of my research for the novel. It is a feature of the residency that we share our work and exchange ideas. By sharing the drawing board of my novel with the other fellows, I was challenged into changing the period from after the British invasion (a time of peace and rebuilding) to the fraught years before it, which were full of war, and leading up to the dramatic fall of Khartoum. I was also encouraged to write more about women, and that was crucial advice. The historical records that exist are all biased towards men, and fiction can give voice to those who have been marginalized or merely mentioned as footnotes.

It takes me a long time to start working on a project. I like to mull over it, to leave it to simmer, until I feel ready to write. I don’t keep an ideas notebook and so I tend to have lots of ideas that evaporate. I interpret their evaporation as proof that they were neither substantial nor fascinating enough. If I can’t remember what struck me as a fascinating idea yesterday, that means that it was not really such a fascinating idea after all! I must be obsessed by a certain image, character, or idea for a considerable period of time in order to commit to the writing.

The character I “found” in the Sudan Archives of Durham University was on a bill of sale for an enslaved woman. I had known that slavery existed in 19th century Sudan, but it was still a shock to see the actual bill with a purchase price and the names of a buyer and a seller. I also found a petition detailing the case of an enslaved woman named Zamzam who had escaped with a stolen item of clothing from her mistress. She had gone back to her former master and it was against him that the petition was raised. I found this situation intriguing and complex enough for me to want to fill in the gaps with fiction. I started researching East African slavery: the extent of it, how it differed from transatlantic West Coast slavery, and how nineteenth century Sudan was a gateway to the lucrative slave markets of Cairo and Istanbul.

TMR: Your book came out less than a month before the current crisis in Sudan began, and although it covers the period 1877-1898, from the years leading up to the Mahdi rebellion until the siege of Khartoum, it is impossible not to read it as more than literature – as a way of understanding some of the history of the people to whom this is happening today. You identify as Sudanese, live in the UK, and your mother is Egyptian! This really is a difficult story to tell given the roles that all of these countries played in Sudan in the 1800s.

Leila Aboulela: The current crisis, which started on April 15th, was shocking in the devastating effect it had on the citizens of Khartoum. Khartoum had been a peaceful city for decades. History can indeed help us contextualize the present. There are echoes, but the current crisis has its own contemporary complications. In writing River Spirit, I was revisiting the triangle of Sudan, Egypt, and Britain, which I had done before in Lyrics Alley, which was set in the 1950s. But actually, because these three places shaped my identity, I was fascinated by the dynamics between them, and it became an easier, rather than a harder, story to tell.

There are also, in the story of the Mahdist revolutionary movement, echoes and parallels with modern-day armed Islamic movements. A severe sense of injustice causes Muslim revolutionaries to rise up against their rulers and denounce them as infidels. This denunciation is extreme, ungrounded in Islamic law, and dangerous because it gives such groups a green light to wage civil war and disrupt society. I also find it quite striking that the Ulema in Khartoum and the Azhar in Cairo were clear and strong in insisting that Muhammad Ahmed Abdallah was not the true Expected Mahdi. Because these voices represent the religious establishment, it is easy for their enemies to dismiss them as being puppets of the government and “supping at the sultan’s table.” However, their arguments, which are both rigorous and impressive, are based entirely on Islamic tradition, and are not a knee-jerk response to threats to the government’s autonomy. I have been equally moved by the accounts of how they were persecuted and overpowered.

TMR: I see some similarities between Salha from River Spirit and Anna from The Kindness of Enemies (2015). They are both wise women who are captives of war. And both bear themselves with dignity and strength, and manage to protect their children. They also both live behind enemy lines and understand the enemy’s perspective. Have you ever been asked if they have Stockholm Syndrome? This strikes me as quite pertinent, given that River Spirit courageously delves into the complexity of sexual politics surrounding enslaved persons and prisoners of war.

Leila Aboulela: The big difference between Anna in The Kindness of Enemies and Salha in River Spirit is that Salha’s enemies are Sudanese like herself. Salha ends up with a family who submitted to the rule of the Mahdi even though her own husband and uncle were completely opposed to him. I don’t think labels such as “Stockholm Syndrome” are entirely helpful in reflecting the experiences of 19th century women held as war captives. The term is dismissive and loaded with disapproval and insistence that the experience is a condition that requires a cure. The human body is designed to heal and adapt — when women find themselves in these situations, responding to kindness and accepting their new circumstances is a coping mechanism that ensures their survival. Once they give birth to children whose fathers are the captors, this complicates the situation further and entrenches the women deeper in enemy society.

TMR: You publicly identify as a devout Muslim and all of your novels feature devout Muslims who are guided by their faith in making difficult decisions. How do you write about faith today? People tend to cringe when they hear of a Christian or Muslim writer who identifies as such. While you may be free to write, people are free to disregard you, not publish you, marginalize you, and patronize you. Who before you wrote in a way that gave you permission to write as you do on the topics that you do, completely unapologetically and unsentimentally?

Leila Aboulela: I came to writing after I had failed at getting a PhD in Statistics. During the academic appraisal in which this decision was made, I was told by the examining professor that I should have read the book entitled How to Get a PhD. This was ironic because I had in fact read the book. What I learned from it was that you should review the literature in your chosen topic and then bring in or add something new. Although I had obviously failed to do that in Statistics, I carried the idea with me when I started to write fiction. I resolved to add Islam to literature written in English, to push the boundaries because the faith was not there — at least not explicitly. In this way, I would be bringing something new to English literature. So I set out to write in the tradition of post-colonial African literature with a focus on the Muslim experience. I was inspired by writers who had been born in various parts of the world and who had come to Britain, such as Tayeb Salih, Ben Okri, Ahdaf Soueif, Doris Lessing, Buchi Emecheta, Jean Rhys, Anita Desai, and Abdulrazak Gurnah.

Writing as a person of faith is a challenge. I remember Tayeb Salih telling me, after he had read The Translator, that members of his generation were shy to include such matters in their work. It can be “cringy” to talk about faith and a challenge to reach readers who are very likely to be skeptical of anything “spiritual.” I believe that words that express faith have to emerge naturally from the character and not just be shoehorned in. I also take care to show characters with different relationships to faith or none at all. And I always take religion seriously; I am never dismissive. I write about flawed characters, not ideal ones. I am also very careful not to preach.

“Unapologetically and unsentimentally” reflects my own personal stance. I also have to say that I have had full support from publishers. The faith elements in my work have never been a problem. I have been working with the same agent and the same US publisher, so I have been very fortunate.

TMR: Your writing provides the Muslim English-speaking person with a mirror in which to see themselves. We recognize your work as both British writing and African writing because you have also won the Caine Prize. What is the market for your books?

Leila Aboulela: When Ahdaf Soueif’s In the Eye of the Sun came out in 1992, it was groundbreaking. More recently, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Elif Shafak have paved the way for more mainstream reading of diverse writers. Readership can grow, but if we keep targeting the same people with things they have liked before, we are not trying to grow the market. We need to assert ourselves more. My books do very well among readers who are specifically interested in the themes that I write about. I find a warm response to my work among the Sudanese and general African and Arab diaspora, in Scotland, in the UAE, and in Pakistan. In the UK, where I live, my books are perceived as somewhat foreign, meaning that I compete with translated books, which account for 5.63 percent of the total UK book market; moreover, the market for translated books is dominated by Scandinavian, Japanese, and Spanish books at the moment. My novel Minaret was the one that reached more readers in the mainstream. My other books were welcomed more by specialist readers, but such groups belong to a younger, growing demographic, so that is exciting. It is always heart-warming to meet readers who have grown up reading my novels, and who were very young when The Translator was first published in 1999. There are more writers of color in the industry and more nuanced responses, so things have indeed improved greatly.

Fabulous arguments1 Bravo!

Thank you Hasna, I am glad you found it!