A prominent physician's testimony urges readers to empathize with life under excruciating, unrelenting bombardment, loss and hardship, and to note the war crimes taking place in plain sight.

Don’t Look Left: A Diary of Genocide by Atif Abu Saif

Comma Press, 2024

ISBN: 9781912697946

I’m not the first to point out that this is the first genocide in history in which millions of humans are in a position to observe hundreds and thousands of other humans as they are targeted, bombarded, slaughtered, hounded and starved in real time. Increasingly, we only observe it if we choose to do so, because there isn’t much being shown anymore in the mainstream Western media. And so people not living the genocide can opt in and out of observing it 24/7 through any of the social media channels on their phones.

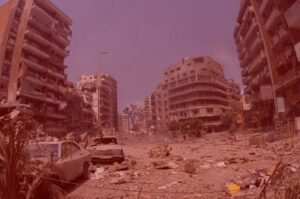

We are now in the eleventh month of the assault on Gaza, and in recent weeks, some of the things I saw when I looked included news of Palestinian detainees being sodomized in prisons and their rapists referred to as “heroic” by Israeli leaders. I saw Israeli demonstrators break into the holding area where the soldiers accused of rape were being detained, calling for their release. I saw, like to many other millions globally, images of body parts being collected in plastic bags after a massacre of people praying at dawn, with the dead designated by weight alone: 70 kg of human remains constituting an adult, and 40 kg a child. I saw, not for the first time, young soldiers grinning at the camera as they razed residential buildings to the ground, detonation by detonation, sometimes synchronized to give them a bigger kick. As if to say, show me the definition of a war crime and I will carry it out to perfection. I, a soldier, just out of childhood, will carry out the extensive destruction of property, not justified by military necessity. I will carry it out unlawfully and wantonly, contrary to Article 8(2) of the 1949 Geneva Conventions. It’s a warped re-writing of proscriptive texts, with glee, in plain sight. One hopes it is hubris. One hopes it will end. One hopes they will be punished.

This is a genocide that has gone on for so long that films have had time to be shot, produced and screened while it continues; for theatrical productions to be performed on London stages while those who wrote the words are still enduring the genocide; for entire diaries to be written and published as it goes on and on and on. The most notable of these is Atef Abu Saif’s Don’t Look Left; A Diary of Genocide, released in March of this year by the Manchester-based Comma Press, run by Ra Page and Basma Ghalayini. The process of compiling the book is a story in itself. This is not the first time that Page and Ghalayini collaborate with Abu Saif, who is a well-established writer. He has not only authored five novels previous, he has also served as Minister of Culture for the Palestinian Authority since 2019. In 2014, Comma Press published the anthology Book of Gaza edited by Abu Saif, and then his memoir of an earlier war on Gaza, The Drone Eats With Me in 2015.

Like much of Gaza’s population, Abu Saif’s family are refugees from what is now Israel. His family originally comes from Jaffa, but he was born in the Jabaliya refugee camp in Gaza in 1973. Since his appointment as Minister of Culture, he has been living in Ramallah. In October he was in Gaza visiting family, together with his son Yasser, 15. On the 7th, he had some official appointments as Minister later in the day, but decided to go to the beach first thing in the morning. “I never thought it would happen while I was swimming,” are the opening lines of Don’t Look Left, written reflectively later about what came to be known as “the first day of the war.” And then Abu Saif’s descent begins, familiarized to us now through news reports and private social media updates. He goes from someone with a home, a life, and a family — albeit under siege and occupation — to someone reduced to living a minute-by-minute struggle for safety, for food, for survival. But on that morning of the 7th, Abu Saif had no sense of what was in store for him, his family, and his people. He was basking in the joy of the early morning sea when “rockets and explosions [began to] sound in all directions.” He carried on swimming, believing it to be a training manoeuvre, one of those everyday exercises practiced by the Israeli army, that would last for an hour or so. But within minutes it becomes clear that this is something much bigger and more serious. He leaps into his car, driving like a madman, breaking all traffic laws. “People jump in front of the car, trying to get a lift. We stop and let five men pile in the back.” Calm to chaos just like that, within the space of a few minutes.

For those of us who’ve been following the situation in Gaza on a daily basis, we’ve become familiarized with, if not hardened by, the barrage of horrors we’ve absorbed over the long months of killing. And so there isn’t much that’s “new” or “surprising” in terms of the information imparted by Don’t Look Left. What the book provides however, is beyond the news. It is a unique account of the extraordinary ability humans have to sustain themselves and others in the most inhumane of circumstances. To be bleak, it could be said to be a glimpse or a “rehearsal” of the future, as the Colombian President Gustavo Petro stated, where weapons are being tested on the urban, trapped population of the Palestinians of Gaza. To be proscriptive, we could say this is a guide as to how we must learn to cope with a dystopic world. Where to hide if at risk of bombing (the stairwell) for example.

There are also small details about everyday life in Gaza that are rare to find in news reports, such as the smitten couple walking hand-in-hand through the bombings, as though the power of their love alone could protect them. In the Afterword, Abu Saif speaks of his friend Bilal Jadallah, to whom the diary is dedicated, and the care he took to feed a stray cat in a way that wouldn’t attract the attention of the drones and make him a target. Jadallah was killed on a journey to the south, on which Abu Saif was originally set to accompany him.

It is true I have left, but I’m still there. All my thoughts are there, all the experiences are still taking place in the ever-unfolding memories of the present.

Diaries like Abu Saif’s, as Chris Hedges eloquently describes in the Foreword, “chronicle not only the facts, although facts are important, but the texture, sacredness and grief of lives and communities lost.” Like the letters of Hossam Madhoun (a number of which appeared in The Markaz Review during the first months of the onslaught), they are detailed accounts of what it means to not just be human and alive, but what it means to be humane: methods of survival, acts of kindness. Beyond that though, writers have a way of conveying humanity through unusual turns of phrase, jokes, gestures, through describing the smell of the air, the resourcefulness of those who have lost so much, but continue to consider themselves fortunate, of those determined to endure, if not for themselves, then for others.

If one accepts the logic of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, one sees in Gaza the systematic stripping away of the two base layers of the pyramid of human necessities, the physiological one of food and sleep as well as that of safety and security. But in reading these accounts from Palestine, there conversely seems to be an expansion of the layers above, those often lacking in the so called “developed” but atomized, capitalist West, those layers of “belonging and love” and “esteem.” Examples abound in these diaries of people behaving according to principles of righteousness and justice, motivated by the desire to do right by others and to serve community before self.

The diaries are, by their nature, quick, rough, urgent; working papers almost. They are lightly edited, quickly produced. Some excerpts were serialized in the New York Times and Le Monde. They are not memoirs of war, written after the events, with the delicacy and polish of Etel Adnan’s Sitt Marie Rose (1982), or in prose as dazzling standard as that of the opening chapters of Mahmoud Darwish’s Memory for Forgetfulness (1987) (both works are set during the Lebanese Civil War). But there is a power to the immediacy of these texts, the frustration felt by the author when writing them. They provide a unique understanding of life under excruciating, unrelenting bombardment, loss and hardship.

The diaries stop in late December when Abu Saif leaves Gaza, after enduring 83 days of bombardment, but the agony, we are assured, doesn’t end there. The bombing, we know, continues until the time of this writing, but for Abu Saif, it goes even deeper than that. Though the requisite Hollywood ending would have his torment end upon escaping via the Rafah border, for Abu Saif, the experience endures. “It is true I have left,” he writes, “but I’m still there. All my thoughts are there, all the experiences are still taking place in the ever-unfolding memories of the present.” For others, such as his relative Widdad, getting to physical safety stripped her of the mental protection that she’d worn like armor while in survival mode in Gaza. Once outside, the young woman, in her mid-twenties, had a nervous breakdown. “When she crossed the border, she suddenly woke up,” writes Abu Saif. “She suddenly saw the truth, she had lost everything — her mother, her father, her brothers — and she must now spend the rest of her life taking care of her sister with no legs and one hand.”

When the media obfuscates the nature of war — as they are doing now, with the genocide in Gaza — honest, detailed, conscientious diaries like Abu Saif’s are essential. “Writing and photographing in wartime are acts of resistance, acts of faith,” Hedges writes in the Foreword. “They affirm the belief that one day, a day writers, journalists and photographers may never see, the words and images will evoke pity, understanding, outrage and provide wisdom.” The implication is that we hope that the wisdom will be absorbed, that it will be profound, that it will be used to push for change, in the way that the Holocaust, gave rise to an international legal system, with the message of never again running through it. The hope is that diaries like these will allow, among other things, to give that international legal system teeth, to pull us back from the brink of the dystopic visions seen by Petro and others, to lead to a realization that Israel cannot be allowed to act as an exception to the laws the international community built to safeguard international peace and security. Abu Saif’s Don’t Look Left is a literary work. It is also personal testimony. As testimony it is evidence of the continuation of war crimes in plain sight. One hopes that international law courts will show the same resilience that Abu Saif did in enduring hardship whilst maintaining a belief in the power of words, of testimony and of justice.

A vital and beautiful review. Thank you, Selma. Indeed, there can no exceptions to international law, no bias, no impunity, no favouring one side. Brutality boils down to one life being affected. After that, we shake our heads and ask ourselves, why are world leaders doing nothing?