Select Other Languages French.

Silva's exhibit Garden State focuses on public and private gardens, which, innocuous though they may seem, reflect a deeper and troubling transformation of land.

Working across photography, moving image, and sculptural installation, Corinne Silva seeks to make visible fractures of historic violence in the land, as well as strategies of survival and resistance in conflict zones. Silva is currently based between London and Athens, and develops work in different ecologies of land and communities. This conversation marks the re-presentation of Silva’s work, Garden State (2015), in Garden Futures: Designing with Landscape at V&A Dundee, on view in Dundee, UK, until January 25, 2026.

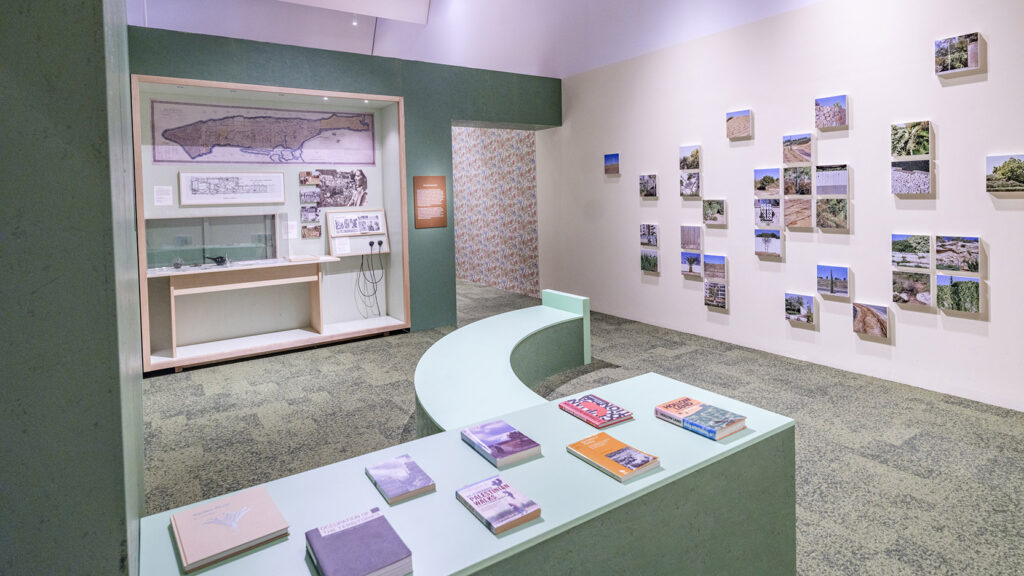

JELENA SOFRONIJEVIC: Garden State is an installation of around 100 c-type photographs, taken between 2010 and 2013, of public and private gardens across 22 Israeli settlements. These gardens are situated on land from which Palestinian communities were displaced during the Arab-Israeli War and the formation of Israel (1948), and the Six Day War (1967). How did you come to make this body of work, which was first exhibited a decade ago, and what does it mean to re-present this work in 2025?

CORINNE SILVA: In school history lessons in the north of England, where I grew up, I learned about Turnip Townshend and crop rotation in the 1800s. We didn’t learn about the British Empire, about territorial expansion, or how we continue to bear the consequences of that history.

The shaping of land, space, and place has long been central to my artistic practice, and it became important for me to educate myself about how colonialism is enacted in the landscape. I became interested in quieter enactments of violence — less visible, but deeply embedded. And where one might also find resistance: in vernacular architecture, in adaptive forms.

When I began working on Garden State, I learned how the gardens in these occupied lands are both material and symbolic evidence of ongoing settler colonization. Here, gardening and landscaping are tools of power, reinforcing political, social, and cultural ideologies.

I was thinking about how the country I was born in had contributed to these structures — and also about how Palestine, like the American West, has long been represented as an empty space. In the U.S. imaginary, the West is a lawless territory, a space for fulfilling desires. Palestine was presented as a land with no people, a space to be claimed. The land, in both contexts, becomes a screen for settler imaginaries. I slowly developed a visual language that offered a different kind of representation.

I initially visited Palestine/Israel and travelled as widely as I could — throughout the West Bank, into the Negev desert — trying to learn to read the land, guided by people who helped me interpret what I was experiencing. In previous works, I had explored how humans shape landscapes through surface, seam, and repair. Here, where land is taken piece by piece and water diverted from wells and rivers, I focused on public and private gardens in new Israeli developments, known as “New Towns” and “Quality of Life” settlements.

By focusing on individual horticultural arrangements, I was thinking about the cumulative effect of small acts that lead to the transformation of a whole land. These gardens, walls, pathways — they lay over older topographies, [palimpsests] claiming space and often obscuring what came before.

Gardens are micro-landscapes. They might seem innocuous, but collectively they have the capacity to reshape vast territories. They’re not just surfaces — their roots extend underground. They’re impermanent, but they can feel like permanent markers.

As for showing the work now — it’s something I’ve reflected on deeply. I’m glad it’s being shown, and that an institution has taken the decision to present it. At a time when many Western leaders are denying that a genocide is taking place and not commenting on the accelerated expansion of Israeli settlement building in the West Bank since October 7th, it’s crucial for institutions to support work that addresses the structures of this settler colonial project. Especially an institution like the V&A, whose own history and collections are so deeply entwined with empire. They have shown integrity and I value that.

TMR: The presentation in Garden Futures includes a map of the areas you visited in Palestine/Israel between 2010 and 2013, alongside additional reading from a plurality of perspectives, including Mourid Barghouti, Meron Benvenisti, Shaul Ephraim Cohen, Edward Said, Raja Shehadeh, and Eyal Weizman. Have you revisited these areas, or remained in contact with people you met? And when in the process of making did you encounter these particular works?

SILVA: I remain deeply engaged with Palestine/Israel. I haven’t returned recently, but I’ve stayed in contact with people I met and built relationships with. While in Ramallah, I met Palestinian artist, writer, and curator Shuruq Harb. She curated the first solo presentation of this work, titled Gardening the Suburbs, at Makan Art Space, Amman, in 2014, and developed a very thoughtful public program that, as well as attracting new visitors to the gallery, also invited them to reflect on their own gardening choices. As part of this, we did a neighborhood walk with a botanist and saw people cultivating roses and green lawns in searing temperatures amid water shortages. It caused me to wonder why I’d thought it was a good idea to try to grow jasmine on my eighth-floor London balcony. Colonial practices can permeate in subtle ways.

As for the books, we present in the show some of the many I read during my research and production period. My process involved intense research trips of two to eight weeks at a time — mostly traveling across the region to access settlements and make photographs, but also meeting other artists and thinkers and NGOs — then returning to London to process my photographic film, read, discuss, and reflect. I continued this cycle until the work felt complete. During this time, I also made a photography and sound work in the region, Wounded (2015), that explores the regeneration of a burnt pine forest on the border with Lebanon.

One key publication that shaped my approach was A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture, edited by Rafi Segal and Eyal Weizman (founder of Forensic Architecture). It helped me to understand that the built environment is far from neutral, it is deeply political (everywhere of course — not only in Palestine/Israel). Here, however, the civilian guise of planning masks a broader military logic. Architectural language — homes, parks, infrastructure — functions to render invisible, to normalize, what is essentially a colonizing structure.

Raja Shehadeh’s writing has also been significant to me. He writes of sarha, “wandering at will,” and his difficulties of being able to do so in the Israeli state-controlled West Bank, increasingly under threat of settler violence. In Palestinian Walks: Forays into a Vanishing Landscape, he writes, “The hills of my childhood are no longer mine. They belong to another country, with its own rules and barriers. But when I walk there, memory persists.”

I joined a rural walking group while staying at the A. M. Qattan Foundation in Ramallah. It was spring and the hills were vivid green and covered in wildflowers. With the current escalation of Zionist settler violence against Palestinians in the West Bank, I’m sure we wouldn’t be able to do those walks now.

TMR: The photographs are clustered by location, from the Mediterranean coast to border zones along the Green Line (established in 1949 between Israel and the neighboring countries of Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria), and into the Occupied West Bank. How and why do their designs change depending on location?

SILVA: As you say, the broken grid of photographs traces details of Israeli suburban settlement gardens extending from the coastal areas surrounding Tel Aviv, across the Green Line, and into the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Many settlements cover over traces of Palestinian villages destroyed in 1948, and as they move west and carve up the Occupied Territories (where they are considered illegal by international law), they isolate Palestinian communities from each other and from their agricultural land.

When the State of Israel was established in 1948 (which the Palestinians refer to as the Nakba or catastrophe), the government encouraged settlement beyond Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. These new developments — “New Towns” — followed the logic of the British Garden City movement, another colonial export. In the 1980s, the original Zionist-socialist ethos gave way to Zionist neoliberalism, echoing Reagan’s America and its white picket fence ideal. There are quite a few white picket fences in my photographs.

With regard to the gardens depicted in the photographs: in coastal areas, the gardens are generic and suburban, not unlike those found in California or southern Spain. Green lawns, palm trees, little variation.

Settlements closer to the Green Line receive government subsidies. I found this financial support was made visible in the materials used: imported paving stones, lush European-style plants. It all felt very familiar, the gardens designed to evoke European landscapes.

Deeper into the hills and valleys of the West Bank are the so-called “Quality of Life” outposts. These are settlements that enact a state ideology, whilst being presented as commuter suburbs. Here, I found more hard landscaping: boulders, gravel, stone terraces. These gardens draw on biblical imagery, evoking the ancient Holy Land. They’re designed to naturalize the settlement, to embed it. These developments rename roads, reshape boundaries, and overwrite memory. They alter not just the landscape, but how it is understood, remembered, and narrated.

TMR: More widely, your work investigates how landscaping, like mapping, can be used to define and claim political territory. For example, The Score (You and I Both Know) (2023) traces a row of linden trees along the River Miljacka in Sarajevo which, local forestry professors have also observed, stood as active participants, frontline witnesses, and now a living archive of civil conflicts in Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

On an individual level, when planting a garden, people put down roots and often make a relation, if not a sense of ownership, over a particular area of land. Are there any particular personal stories from these photographs that stand out to you, in representing these complex, and oversimplified, disputes over contested territories?

SILVA: Botanical classification — like landscape photography — has long played a role in empire building. For the 2016 Garden State monograph, I invited botanist Sabina Knees to collaborate on a section of the book. I didn’t want her to solely identify or catalogue the flora, but to further complicate the relationship between plants, planting, and colonial practices.

Together we created a table: A Taxonomy of Colonising Plants. It followed some scientific principles, but was also more fluid, subjective, proposing questions. In this table, Sabina chose some of the plants seen in the images to write about. I learned a lot from her selection. She wasn’t interested in the majestic date palm, and instead pointed out the “adventitious weed flora” growing at its base, which made use of the water being directed to the larger plant.

I learned from her that Bedouin and Palestinian communities planted the prickly pear cactus — originally from Mexico — to corral their animals. When you see numbers of these cacti in this landscape it carries a trace today of that earlier use, of who was there before.

I was also fascinated to discover from Sabina that botanists don’t like photographs of plants to identify them, they prefer illustrations. Photography is an unreliable witness.

TMR: Can you talk more about the formal aspects of the work?

The piece takes the form of a broken grid, clusters of unglazed, medium-format photographs, each 25 centimeters square. These images loosely map the 22 settlements I visited. The physicality of any work I produce is important to me, whether it’s two or three dimensional. I’m always curious as to the viewer’s bodily interaction with and perception of the scale and dimensions of a work. We privilege sight over other senses, but a photograph is nevertheless encountered with the whole body.

At the time of making Garden State, I was interested in where landscape photography’s limits lie in terms of representation, and in attempting to push those limits further or reveal the shortcomings and potentials of trying to depict a partial view. I wanted to disrupt the language of the monumental landscape photograph, the Renaissance-derived idea of surveying land from above — as if to own it.

There’s little spatial information in the images, and I used a shallow depth of field. The viewer is held close to the surface. It becomes claustrophobic. There’s no horizon line until the far right of the installation, where the gardens depicted in the photographs begin to penetrate the Jordan Valley area of the West Bank of Palestine. By offering only fragments, it perhaps causes the viewer to imagine what they don’t see, what lies around and underneath and beyond.

TMR: Garden State was first presented in solo exhibitions of your work, in the Makan Art Space in Amman, Jordan in 2014, and the Mosaic Rooms in London and Ffotogallery, Wales in 2015. At the V&A Dundee, the installation is placed in conversation with works by international war photographers like Henk Wildschut and Lalage Snow, as well as Thread Memory, a concurrent exhibition of embroidery from Palestine curated by Rachel Dedman. How does your relationship with this body of work change in the context of solo and group exhibitions, or in relation with others’ work?

SILVA: Rachel Dedman’s beautiful show Thread Memory: Embroidery from Palestine provides a vital counterpoint to Garden State. It’s a celebration of Palestinian art, craft, and heritage and an acknowledgement of the history and ongoing importance of the Palestinian presence in the cultural realm as well as in the world at large at such a terrible time for the Palestinian people.

As for my participation in group shows, I always enjoy seeing how curators draw out new associations. At the V&A Dundee, there are connections to be made with many works, in particular Jamaica Kinkaid’s engagement with gardening and empire. In terms of spatial proximity, Garden State is positioned directly opposite a display of the Green Guerillas Collective, a New York City community gardening project that began in the 1970s. This was and continues to be a beautiful initiative that formed community and enacted environmental justice through urban gardening projects. I find this a powerful antidote to what I encountered when making Garden State, offering an example of courage, a sense of solidarity and of what we can make possible.

•

Corinne Silva’s monograph Garden State is published by The Mosaic Rooms and Ffotogallery and is available here.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)