Accused of terrorism against the state for aiding and abetting fellow Syrians fleeing Homs for Damascus, former prisoner X talked to TMR about his long journey to asylum in Belgium.

TMR: You say that even though you’ve found yourself in a good situation and while other Syrians are often doing well, you still feel “homeless.” Is the attachment to Syria so great?

X: [There are] many factors…I would say not only Syrians at my level but people who achieve more (and many people achieve more than what I have in Europe) still feel homeless…Home for them is Syria. But it’s not home anymore because they can’t return. You cannot consider a country as home if you cannot go there.

TMR: You say they can’t find home in their new countries; is it because they can’t find the level of comfort they like or they can’t find enough other Syrians to talk to? What is the reason?

X: It’s more about the feeling than the activities or the food. You don’t belong, it’s not home.

TMR: Many people have become refugees, many have left home. Milan Kundera, a writer from the former Czechoslovakia, fled Prague, emigrated to France, eventually became French. Samuel Beckett left Ireland, went to Paris, started living and writing in French, became a citizen…Other people from other places move to new countries and they adapt; why not Syrians?

X: First of all, I can’t compare a Syrian moving to France to a Czech or an Irishman moving to France, because that’s still European. The differences are not big. If you talk to Syrians who move to Jordan, for example, they have a better situation, because it’s still Jordan, you’re still within the same bubble, BUT you don’t have good opportunities over there, they’re not treated well by the Syrian government, they’re still stigmatized because they are refugees. But myself personally, if you give me the choice to live in Jordan and have the same rights that I have here in Belgium? I would choose to live in Jordan because I would still feel that it’s my environment. It has to do with the Syrian attitude; we are very attached to the country, to Syria. If you talk to Egyptians, maybe Jordanians, Lebanese, they always wanted to leave their countries and migrate, move somewhere else. Unlike the Syrians; even if they migrate they keep talking about going back to Syria. They will buy houses in Syria. They will act as if they will end up living in Syria when they retire or when they finish what they’re doing abroad. I would say yes, we are more attached to our country than other nations. It’s obvious. We would prefer a moderate, decent life in Syria than a good (lavish) life somewhere else.

TMR: I talked to another Syrian the other day, a writer. She left Latakia with her family at the age of 15 and a half and moved to the UK. She became a BBC producer and went back to Syria in 2010 to do a series of documentaries, and then she published a novel two or three years ago. She said there was something about Syria that was really alive…electric, something about the land and the people, as if it had an energy, a vitality that she was trying to explain. She said the people and the country are very alive, it’s something different…She noticed it again when she went back and said, “it’s still in me even though I’ve been a British citizen, I grew up in the UK from the age of 15; I’m still very attached to Syria.”

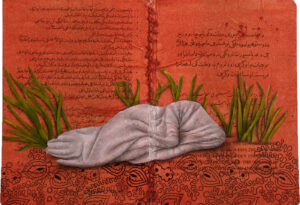

X: Well, I don’t want to say that Syrians love their country more than other people do, I can’t say that, I won’t claim that. But I can say that there is something spiritual in Syria, there is something mysterious you can’t describe but you feel it, even as a foreigner. My wife is Jordanian, for example, she’s not Syrian, but she has the same feeling. But she does not have that feeling when she goes to Lebanon or Dubai. I would say there is something spiritual in that land.

TMR: The only time I’ve heard anything like this is when Jewish people say they went to Israel and they felt something spiritual, because it’s the Holy Land, it has its ancient history and so on. Is it maybe because Syria is rich in history and monuments and…

X: Maybe, when I say spiritual it’s not in the religious sense. The energy maybe is a better word to use. There is something…

TMR: You said in one of your emails that you were never really very political, but you wouldn’t have pictures of the leader on your schoolbooks. What were you like in high school, in university? What vision did you have for yourself? You didn’t imagine that you would become a refugee, so how did you become an activist?

X: No, no, no. Here you have two aspects, a general one and a personal one. Generally speaking, Syrians, we don’t talk about leaving the country. We always prefer to stay. We would leave to make a better living, to have better education, but we always talk about going back. We come from an upper middle class family, we have our own family business, everything is obvious, I know where I’m headed, so I had no plans to leave the country, it’s just what happened that juxtaposed my safety versus staying in the country. Our family business was a paint company, we manufacture paints, decorative paints. I didn’t have plans to leave, no, not at all…

TMR: 2010, 2011, you were working in the family business at the time, minding your own business, and then you saw what was happening in Deraa? How did those people get to you? The people you hosted?

X: They were from Homs, actually. That was actually in 2012, when I hosted those people. Through friends. We were running, let’s call it an underground helping system, okay? Providing food, shelter, proper accommodation, necessities to those people fleeing their cities and towns. Most of them came through that network.

TMR: How did you get involved in that network? Isn’t that kind of dangerous?

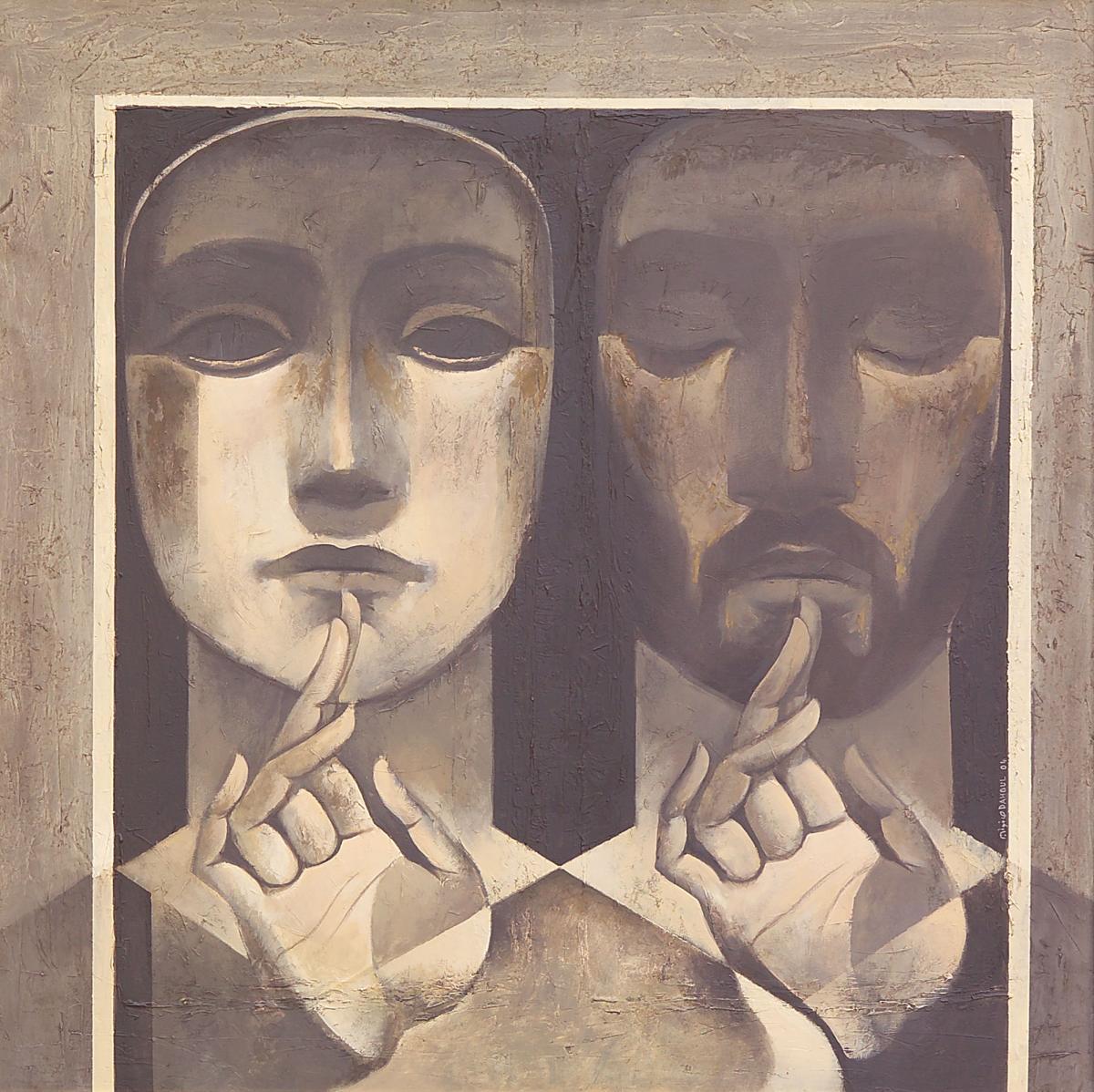

X: It’s not dangerous—it’s extremely dangerous. You have to take sides, you have to decide, which side you’re on. Otherwise, you end up as one of those we called the silent majority.

TMR: So you make a decision you want to help people, and you know — just as a criminal who gets caught knows he has to do X amount of time for the crime — so you take that risk and you know that if you get caught, it could affect people around you, so it’s even more dangerous.

X: It could be, yes, but what is the alternative? You have three positions to take, in 2011: Pro-regime, pro-revolution or silent majority. Okay? You have to fall into one of these three categories. Of course you can be an extreme pro-regime or an extreme pro-revolution, or moderate, but you have to choose one of these three. I put those three options in front of me. Definitely I’m not going to be pro-regime, that’s for sure. Between silent majority and the pro-revolution, I would say because I understood why we got to that point, and because I had a dream that we need to move the country from this situation to another situation, and that cannot be done if everyone is going to say if I act, it’s going to be dangerous to the people around me, so I’m not going to act; then nobody will act and we will just stay as we were. So yes, it was an adventure. We lost the adventure, we did not win, but we tried.

TMR: So no regrets, on your part?

X: [hesitates] Personal regret, no. I would rather [be able to] say to myself, today or 20 years from today, that when I saw men and women being slaughtered in Homs, I helped their families, and when I saw the injustice applied by the regime, I had the courage to say NO to that. It destroyed my life, but I won myself; I won my self-respect. Rather than saying well I knew it wasn’t going to work, I knew the revolution is going to fail, so I prefer to be one in the silent majority. I think I would not be able to stand the shame behind that, so personal regret, no.

TMR: You say you saw people in Homs being slaughtered: was that news on television, or did you hear about it on social media, or did you visit Homs?

X: We had two kinds of media at that time, actually let’s say we had three: we had the official media, showing that everything is great, nothing is happening, it’s just a bunch of [terrorists]; and we had the international media, Al Jazeera, Al-Arabiya and they will show you what their governments want the world to see; and we had the free media, the activists on the ground, that were taking videos, putting those videos on Facebook or other platforms and bit by bit we learned to tell the good ones from the bad ones. So we knew who to follow at that time. A video about families being slaughtered in Homs? The official media would never show you that, they would never mention it; actually if they did mention it they’d say that a bunch of terrorists received money from Qatar and they went to this village and slaughtered 200 men, for example. Those videos were more like the turning point for us, especially the first few videos from Homs, that would be around April 2011, because it started there, and we knew that it’s gonna come to us. So it’s either you act and do something and fight while the action is not in your home town yet, or you just sit there and you know it’s gonna come in the end.

TMR: Were you guys living in the old city in Damascus or another neighborhood?

X: We lived in Ruken el Din (northern edge of Damascus). It’s still within the city. It’s not the old town, not downtown Damascus…We had some apartments that we did not occupy at that time, so yes when I got the call that two, well actually three families from Homs just arrived in Damascus and they don’t have a place to stay. You would offer your place to stay and then you would go and buy enough food, necessities, to you know, make them comfortable.

I’ll tell you one thing that might be interesting. In prison — which is another subject, it takes weeks and weeks to talk about that, because it’s not just prison, it’s a life inside, it’s a world by itself — but I will mention this point. I was having this conversation with one of the torturers inside the prison. And I said, hey why are you doing this to us? What is this big mistake that we made? We just hosted women and children from Homs, and we provided food and accommodation. What is so bad about this? And he said we are punishing you for doing that, because their men continued to fight because they knew their families would find help if they went to Damascus, so they risked and they went to fight knowing that their families would be well taken care of. Whereas if you hadn’t provided this opportunity, their men would say we’ll have to stay with our families to take care of them; we’re not going to go and fight. For the regime, working as a humanitarian, providing help to those families is still a political act, because you are facilitating those fighters. You’re giving those fighters a chance to fight knowing that their families would be okay. Which means you are part of being in that army.

TMR: I read a Human Rights Watch report in which a number of former Syrian prisoners were interviewed, where they talk about torture methods…So they didn’t come to your door to arrest you; you heard you were going to be in trouble so you decided to leave and you were caught at the border?

X: Each person has his own case and there are plenty of factors. Sometimes it’s luck, sometimes it’s coincidence, you know? In my case it was lack of communication between different departments, so my name was put on the list at the border, but they did not share that list or my name with those departments that arrest people at their homes. My theory is different, because my first session, investigative session, luckily I had a smart guy, an educated interrogator. He started from the end, not from the beginning.

He said okay, we’re not going to waste time. You are an educated person and I hope that we’re not going to give each other a hard time. He put a CD in and I listened to all my phone calls during the previous six months before they arrested me. Okay? My theory is that they wanted me to stay active inside the country, under surveillance, to know all the people I’m working with, and they put my name at the border so that when I try to leave, I don’t escape. Because I was a bit of a bad ass, I would go to those risky places, I would stop at barricades [checkpoints], they would run my name and check if I’m wanted or not — I’m talking about Damascus suburbs. And they would just let me go. I’m pretty sure some of them knew that I was going there to do something. But they did not act, so my theory was not that it was lack of communication; they wanted to get all those people I was working with.

TMR: Tell me about the time you spent in prison, which one it was, where it was…

X: The worst, 215. Inside Damascus. It’s the same one Caesar [Muhammad Mustafa Darwish] was in, you know those photos from the Violation Documentation Center in Syria? If you know the new American sanctions, you should know him, it’s because of this defected officer from military intelligence 215, he testified, he used to be a photographer, because they take your photo three times, so he was that photographer and then he apparently made copies and those photos of dead bodies, you’ve seen them right? No? Caesar Law, the American sanctions exist because of those photos, they came from that prison called the Military Security Dept 215, but still there are many subdivisions inside that department…There’s the Airforce Intelligence Branch, that’s a different one.

TMR: How long were you in 215?

X: Not long, actually. Well, I’ve been to six of those, not only one.

TMR: I don’t know how you can smile about it, because didn’t they torture you in some of those places?

X: Oh, surprisingly, how do I say this? It’s a pleasant experience; it’s not as bad as you think. I mean, you’re not a criminal, so there’s no shame here. Okay? At the same time, you’re not a hero, you’re just one of those people who collectively decided to improve the lives of their children in the future. So you’re an animus at the same time, which makes you feel that you did not do it to please your ego. That’s a pleasant feeling. Now inside [the prison] you will learn how much you are capable of withstanding. You will learn what it means to survive, you know. You will discover a new depth in your personality that you could never discover outside [prison], because you have no similar experience outside.

TMR: I think very few people are looking for a prison experience.

X: Well, you don’t look for it, you don’t go after it, but when it happens it’s better that you benefit from it — because it’s going to happen anyways. So you either learn from it, use it to enrich you as a human being, or you just talk about it as a very bad experience and you just look at the bad sides and you have all this self-pity around yourself.

TMR: So what did you get from it?

X: [smiles] Plenty of things. Even the friendship — the friends you make inside, you’ve never been in a situation like this. You have school friends, you have colleagues, you have friends from your neighborhood, I don’t know, if you served in the military, you would have friends from there. But the friends you make inside are different. The connection between you and them is different. And you stay connected somehow with those people you meet inside. It teaches you things about how to handle stress, fear, worries, because there’s nothing like the stress inside, nothing like the fear inside. So everything you face outside [smiling] is a joke, actually.

TMR: Are you in touch with anybody you were in prison with?

X: Yeah, of course, of course. I have one in Germany, I have one in Turkey, I had two in Syria, but we don’t communicate [now] because we don’t want to…actually we had a reunion once, in Amman, in Jordan…I don’t have any plans [to write about my experiences] to do that to make money, or post on Facebook. The reason you would do that is to share it with people who know what you’re talking about.

TMR: The reason I mention it actually is…we’re going to do an issue of The Markaz Review on prison literature and prison experience.

X: We were planning to have another reunion in Turkey, but because of coronavirus we couldn’t pull it off. For us, it’s not because we want to be famous, because we’ll be anonymous; our names will not appear. It’s just because we all believed that prison experience can be pleasant sometimes, and our hope is that someone from the regime will read that and we wanted them to feel angry and mad; that despite the torture, despite all the horrible circumstances, we found time to enjoy, we got out with good memories, and we’re thankful for that opportunity that we’re now friends. So we want to tease them somehow.

TMR: This sounds like satire, it reminds me of our comedy show — it’s not exactly what you would expect to hear. What did you eat in prison? Did they feed you hummus and pita? Because in American prisons they’re obliged by law to feed you, I don’t know, two meals a day…

X: [laughs] Whatever you imagine, it’s not it. When you say American prisons, two meals a day, it’s not like that. I did not stay long, personally; I stayed 44 days. I went in weighing 82 kilos and I left weighing 63. In 44 days. So do the math.

[chuckles] They fed us very little, enough to survive, not to die.

TMR: When you say very little, was it five chickpeas and a little piece of bread, or what?

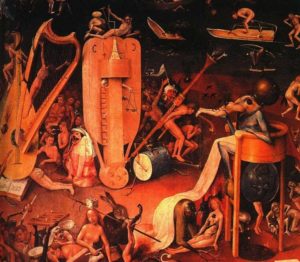

X: Could be that little, sometimes. Three or four green olives and I would say 50 grams of bread. Less than half of a pita bread with three-four green olives. Sometimes we would get halva, you would get a piece the size of an apricot, maybe. One potato, just boiled. Every once in a while, you may get a sip of yoghurt, you gotta imagine the situation. It’s a small room, I would say six by four meters, seven by five, I can’t tell, but it’s definitely not more than 40 square meters, and the number [of prisoners] inside fluctuates between 50 and 80.

TMR: So you have no room to lie down?

X: We do shifts. And then they would open the door and they would give you a container of yoghurt and it gets passed around by all the people inside; you take one sip. So that’s a treat, that’s a treat. So technically what’s enough so you suffer and survive. They can easily stop giving you food and then you die of hunger. But they want you to survive, they want you to stay alive for a while, at least, but at the same time they don’t want you to survive comfortably, they want you to suffer to survive.

TMR: Those 44 days, how old were you at the time?

X: 32.

TMR: I remember where I was when I was 32; I had just met my first wife and we were dating in Los Angeles.

X: A big difference…well, I’m pretty sure your parents maybe suffered. Because to get your country to stability, a generation has to suffer, right – don’t you think?

TMR: For the United States, it was the World War II generation that had to. Not mine.

X: Your country right now, France, they have this liberty, this stability, but it was not free.

TMR: No, they paid with two world wars.

X: Yeah. So for our country the plan was to get to where France is right now, and our generation was the one that was supposed to take the country to that point, but simply it didn’t happen. We lost…

TMR: Why isn’t what happened in Syria a civil war?

X: Because I would imagine that the definition of the civil war is a fight between two equal parties in a country over power or over, you know, advantages. While it’s not the situation in Syria; it was an uprising, a revolution, in the beginning, so it’s people, part of the people against the regime. There’s no one group, there’s no one leader on the revolution side. That is to say, we have this leader in this party fighting that leader in that party…That’s number one. Number two, civil war is a war between the inhabitants of the same country. Now we have Russian, Iranian, Lebanese, Iraqi, Afghani, Americans, Turks, Saudis, you name it, they’re all involved. So it’s not a civil war.

TMR: Good point, and that’s why it can often be so confusing. And why you hear many different stories; you hear that Assad was responsible for [the chemical attack in] Gouta, then you hear it might have been al-Nusra or the Free Syrian Army…And of course, Israel has been bombing Syria with impunity now for years. And it’s not even in the news.

X: It’s not just lately; they’ve been doing this for 40 or 50 years. It’s just now we have better media so we can hear about those incidents, but they’ve been happening thirty years ago, but because we didn’t have these tools to spread the news, and they have been getting away with it.

TMR: Israel has been bombing Syria even when there wasn’t a war going on? I don’t know, 20 years ago?

X: They would send bombers every once in a while. It’s complicated…I would describe the relations between Israel and the Syrian regime, it’s like a married couple, they fight, maybe they fight during the day but they sleep in the same bed at night. The Syrian regime is there only because Israel wants that, okay? For Israel and its security, they prefer to know their neighbors, they prefer to choose them if they can, and if they don’t choose them, then they prefer to cut deals with them. And the deal will be like okay, we will mobilize the world to keep you as regime in this country in exchange for guaranteeing our security.

TMR: Was it with Hafez that they made the deal, or with Bashar?

X: It’s one chain of action, so the father started it and the son continued doing it.

TMR: Since that’s the case, why does Israel continue bombing Syria?

X: Because at some point, sometimes like in Lebanon, early eighties for example, the Syrian regime will try to win some points to enhance its negotiating position, all right? For example, in Lebanon, the Syrians supported the Palestinians, the PLO, but not because we love them (of course not me personally), not because we want them to liberate their country, just because Assad wanted to have one more card in his hand to use against the Israelis. At the end of the day, they have a deal, they are partners, but every once in a while they need to have more tools in their hands, leverage. So for the moment, Israel is bombing those cards, and when you look at the accuracy of the targets they bomb, you can easily say they can kill the guy in his bed if they want. But they won’t do that, they don’t want to do that because he is their partner. He kept the Syrian-Israeli border safe for a long time.

TMR: If the Assad regime goes and you have the Free Syrian Army, al-Nusra, whatever’s left of Daesh and the Kurds, etc, you have multiple groups and you don’t know which one is going to wind up controlling the country. It would be chaos — it’s already chaos but it would be even worse.

X: Yeah. It’s now a mess but at the beginning, in 2011, I always ask myself this question: why did the Israelis push toward chaos in Syria and not partner with this revolution, support the revolution somehow, so they win? And they have a stable democracy let’s say, and we become just like Egypt or Jordan, with a peace treaty between the two countries—which is going to happen in the end, with or without the regime, but instead of having a deal with a strong neighbor, it’s going to be with a destroyed neighbor. So for Israel, Syria will now need at least 50 years to reconsider any of their war actions. So Israel now on this side is safe for 50 years because this country is destroyed.

TMR: It’s tragic for the people of Syria, but a tragedy in one place is a tragedy for everybody. It brings down all of us.

X: Of course, at least morally.

—interview conducted by Jordan Elgrably