Remembering and celebrating the old, new, destroyed, erased and dead of Palestine, a very personal artistic response to a nasty, ugly war.

Malu Halasa

“It’s very painful,” says Hazem Harb, referring to the continuing anguish he feels during the war on Gaza. The Israelis’ arrest of his father Riad Harb in February, the disappearance of the 70-year old with a heart condition and the knowledge that he was tortured during captivity — told to the family by a teenage boy imprisoned in the same facility — turned the artist “upside down” and “back to zero.” Eventually Hazem Harb’s father was released; however, feelings of raw upset remain for his son.

“What was public suddenly became intensely personal,” the artist admits from his studio in Dubai. “I don’t know how to explain it. I’ve never experienced anything like this in my life.” He had always paid close attention to events back home in Gaza, where he grew up. But this war has been more visceral, painful and personal.

“I was following my family’s situation and at the same time dealing with my anger, sadness, and trauma,” he says.

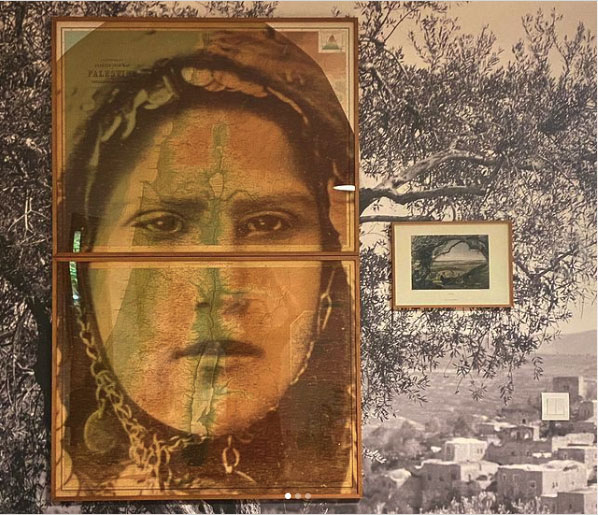

A layered precision has characterized much of the artist’s work. In collages, such as “The Mother Land,” 2022, a woman with an overlay of a 1930s map of Palestine on her face stares into the near distance. Behind her, an olive tree stretches out towards a village. In his art, Harb has used archival documents and other ephemera from Palestine, even family portraiture. The five panels of “The Family Tree,” 2021, were taken during the 1945 engagement of the scion of a prominent Palestinian clan, the al-Dajanis, custodians since the 16th century A.D of King David’s Tomb in Jerusalem. Tree branches, like veins, cover their bodies; a prominent gray, geometric triangle intrudes on the celebratory family setting, as though to intimate the dissidence between the past and the always intruding present.

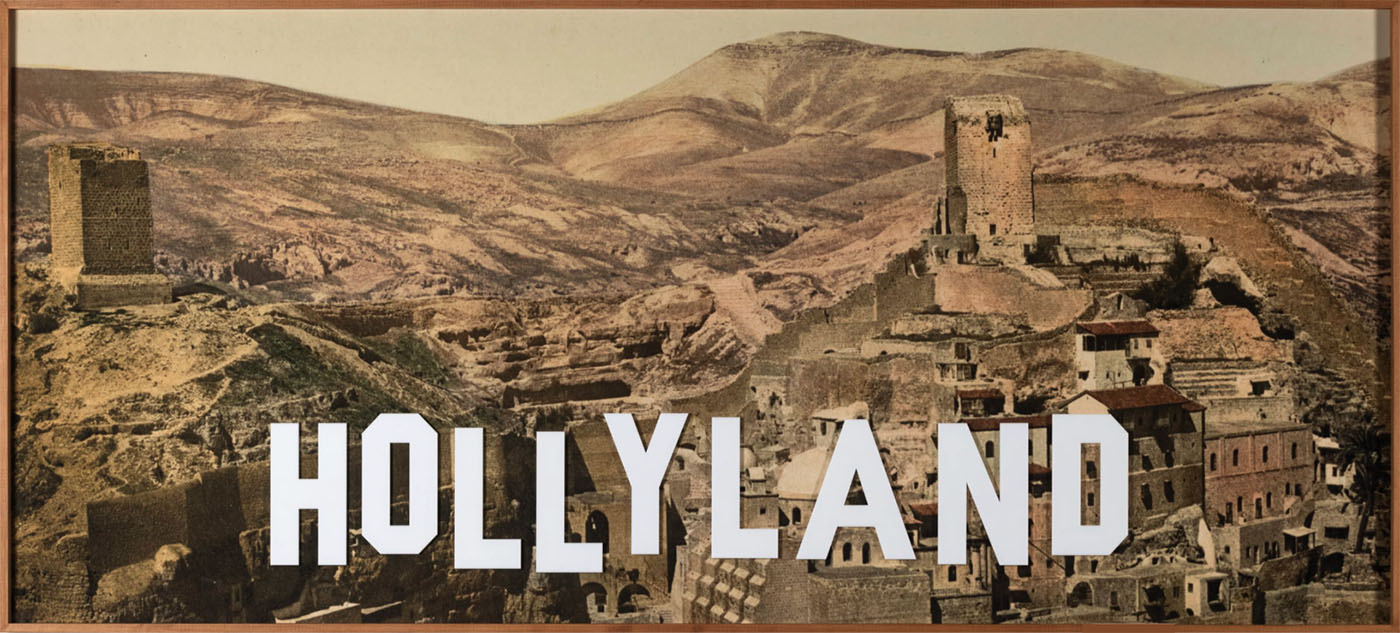

In Harb’s artwork, block lettering has been used to great effect — Holy Land vs Hollywood. Hollyland, the title of one of his 2021 series, hangs over historic sites of the Dead Sea or the monastery Mar Saba like the Hollywood sign in the Santa Monica Mountains. In the past Harb even relied on a social media trope, framing, in the 2015 Tag series to isolate historic figures and locations, in Palestine.

Installation, too, is another of his forms. “Liquid city,” 2021, constructed entirely from stacks of pristine olive oil cans, resembles a cityscape. The allegorical work is reminiscent of Ghassan Kanafani’s short story “Men in the Sun” and the countries, from Israel to Kuwait, which have benefited from cheap Palestinian labor.

This art interrogates what it has meant to be Palestinian before the Nakba catastrophe of 1948 and the experience of dislocation, violence and erasure that has come afterwards.

“Let’s call them ‘contemporary’ works,” Harb tells me over Zoom. They “come [from] a quiet situation, where I research, do my own analysis and photography.” The collages, in particular, take time to produce and are made “in a very intimate, private” way, he explains.

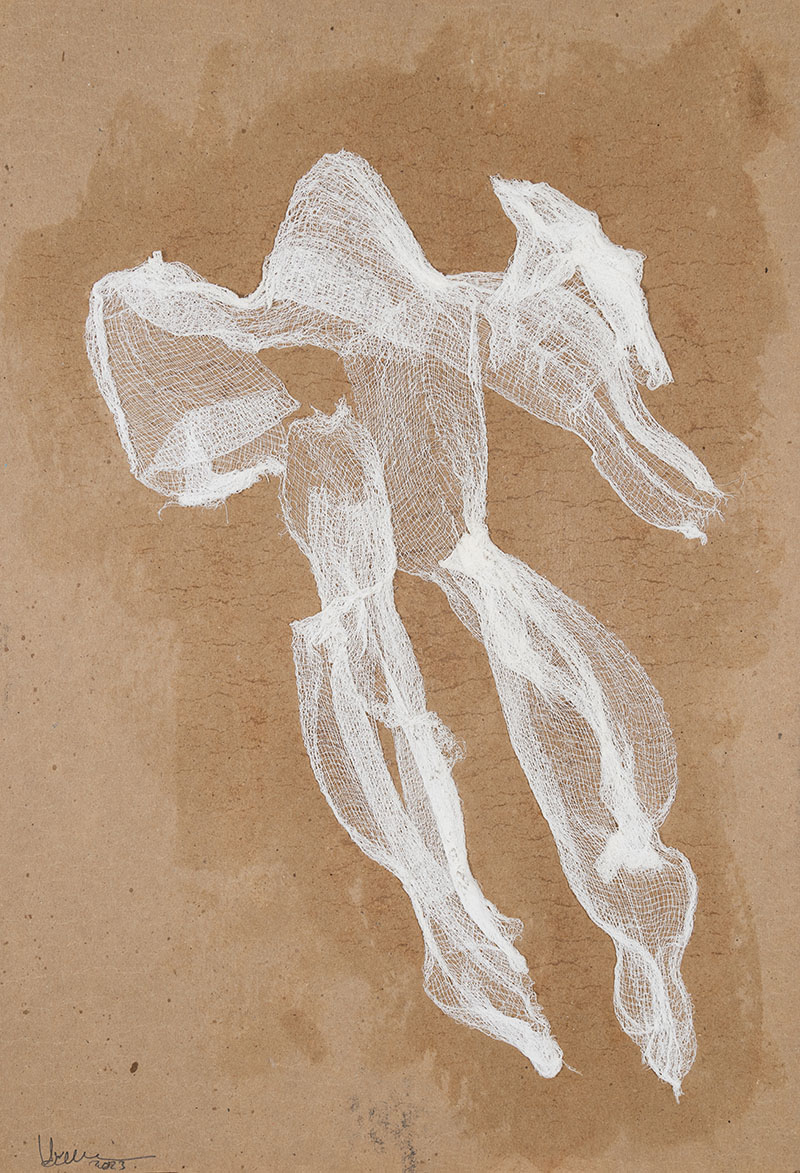

That seemingly changed overnight with the assault on Gaza. The war took him back to basics of drawing and painting, activities he eschewed for nearly a decade. Instead of right angle delineations and exactitude in his artwork, his lines have suddenly become more flowing, curved. Ethereal, even ghostlike, they play with the ambiguity between abstraction and reality.

He calls his 2023 charcoal on fine art paper series, Dystopia Is Not a Noun, drawings from “the gut.” The physical closeness between himself and the page matters to him greatly.

“Charcoal,” he points out, “is a material you use with your body, with your hand. With a brush, there is a distance between your hand and the surface.”

The drawings, exhibited last November in Tabari Artspace, in Dubai, capture his frustration and torment during the war. One, for me, stands out: the view from behind of a lone figure, standing on what seems to be rubble, with a raised hand against an unjust sky. The drawing suggests both vulnerability and resistance. The large scale of these works — 78 3/4 x 47 1/4 inches — is not immediately apparent when they are viewed on a computer monitor. During our Zoom conversation, Harb aims the camera on his phone to the framed and mounted charcoal drawings, which take up significant wall space in a meticulous artist studio. He then goes on to show me the large, long room, with its tables big enough to work on and the many cabinets that store his research archives and art supplies. Strong spring sunlight streams in from a door that leads out onto a balcony.

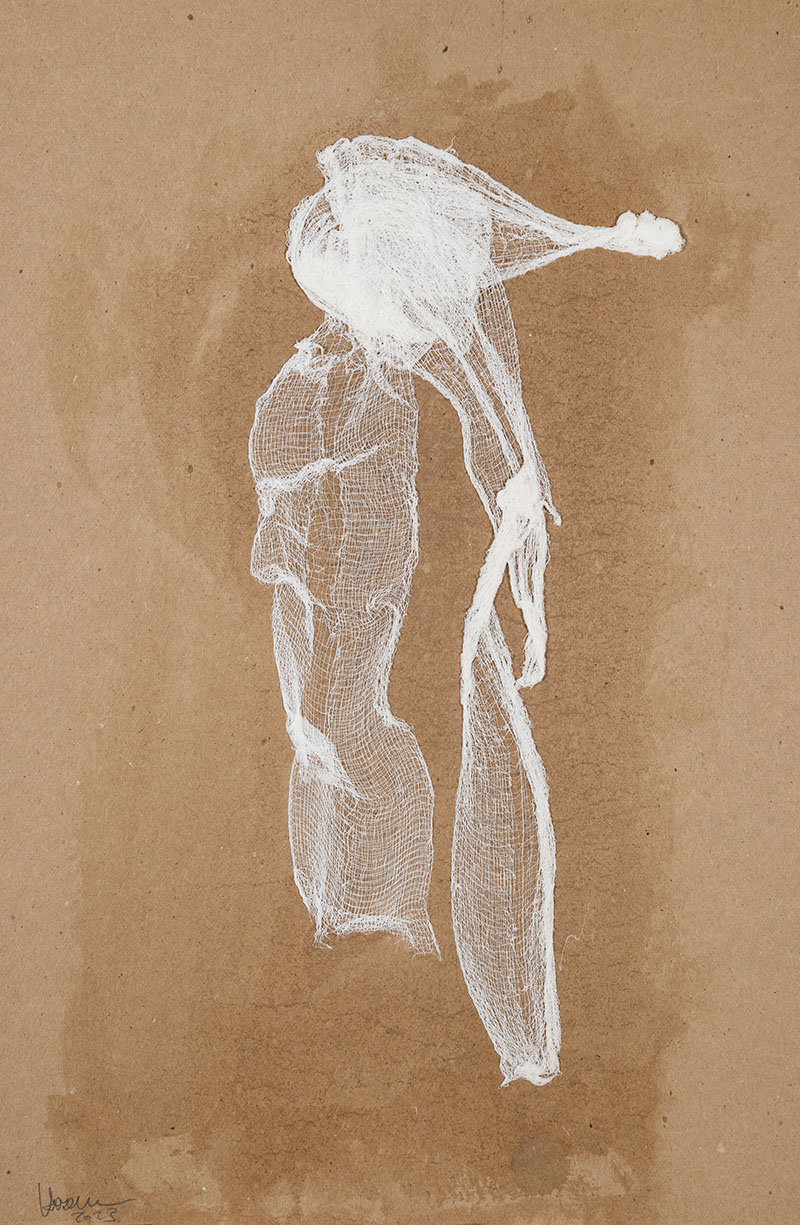

Harb has always been a prolific artist. Gauze, the series he produced during his father’s captivity, was exhibited at Tabari Artspace, earlier this year. The arrangement of strips or swathes of fine, white gauze, on a brown, fine art cardboard, is stark and shocking. The work is deeply melancholic. Their abstracted shapes have the effect of Rorschach prints; the psychological state of the viewer determines the depth of meaning. For the artist, it again goes back to this intimate act of making.

He stresses, “In Gauze, everything is also made by hand.” Collapsing the distance between how he feels at that moment and the 22 framed artworks has given the series a deeply personal relevance. He tells me he plans to keep the artwork for himself and has told his gallery he doesn’t want to sell them.

For him, there are many layers of meaning in his choice of material. The English word for “gauze” — originally شاش [shash] in Arabic — is said to have its roots in Gaza. The material’s historic and contemporary uses have been in the wrapping of wounds. It has an unmistakable resemblance to the white cloth, which has been enshrouding the bodies of the Muslim dead, images that have become prevalent due to wars in Gaza and Syria. It is also connected with Harb’s own development as an artist.

He says, “This material is one I worked with in Gaza when I was eighteen or twenty, making my collages, installations, and performance.”

He picks out an album, and shows me its contents. It includes early art work that his mother collected when he was still living at home. “She kept everything,” he says, stopping at the drawings and seemingly taking them in anew, “Even the lines are very figurative.” Harb had been one of eight children and had grown up during the First Intifada.

We speak about his mother and a box of old photographs that she kept, which he repeatedly looked through. It was an experience that perhaps kindled his early interest in archival imagery.

Interestingly, it is the photographs she collected of a 2003 live art performance by her son, still experimenting as a young artist, that make an impression. On stage, Harb’s head and body are entirely in white gauze. He looks incredibly sculptural. Then there’s the sudden realization on my part, that year Harb had witnessed the bombardment of F-16s yet again on Gaza City, with predictably American weaponry that had been sold to the Israelis. Yet absolutely nothing dissuaded the young Harb from studying drawing at the YMCA or going on to do live art performances. He realized a dream to formally study abroad, art at the IED Istituto Europeo di Design Roma and stage at the Academy of Fine Arts of Rome. Palestine “just is,” as he once said in an interview; identity, history and place have always been at the core of his subject matter. He also utilized gauze in his 2008 video installation “Burned Bodies,” shown in an old slaughterhouse turned cultural center, Città dell’Altra Economia, in Rome.

According to the artist, both Gauze and Dystopia Is Not a Noun are “urgent” works. He thinks of them “art de l’automatisme,” creative expression from the unconscious, which André Breton wrote about in in 1924, in Manifeste du surrealism.

Harb stresses, “As an artist and as a human being, you can’t escape from the fragility you have inside. There can be a rigidity in sadness, but a power too. Art is resistance, and that it is, also, resilience.

“I had the exhibition a couple of years ago, Power Does Not Defeat Memory. Power cannot defeat even art. Being an artist is a huge responsibility. Art should leave behind a legacy — so imagine something of your own individual and collective memories of a country or place.”

In my experience, Zoom conversations are usually static; there is a certain predictability to online interviews. This isn’t the case with Harb whose emotions appear close to the surface. He eventually confesses, “This is the first time I’ve dealt with art in a painful way. I’ve had many different experiences before. I’ve even worked [through] grief. But this time, I went into the work with pain and the pain comes out in the art.”

Then I posed a question that the filmmaker and critic Nora Ounnas Leroy asked after she reviewed an exhibition of “exile” art for The Markaz Review. She had pondered out loud: where is the Palestinian National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art?

This line of inquiry surprises Harb. His mood suddenly lifts and you can hear it in his voice. “I was born in Gaza and grew up there. I’ve always felt Gaza is a very beautiful Mediterranean city, really stunning. I even had a house on the beach. I always thought to build an open museum on the beach with most of my private collection of books, maps … and of course to have some of my works and other artists’ work inside this museum. This was my dream.”

He continues, “I did realize some of this dream. I did build an apartment there, a legacy to my mother who collected ceramics and other objects. Of course this apartment is gone.” The family home on the beach, in Rimal, was blown up by Israeli soldiers after they entered the building, separated the men from the women, strip-searched and arrested the men, including Harb’s father, brother, brother-in-law and nephews.

“Inshallah,” says the artist, with a determined glint in his eye, “we will rebuild it.”