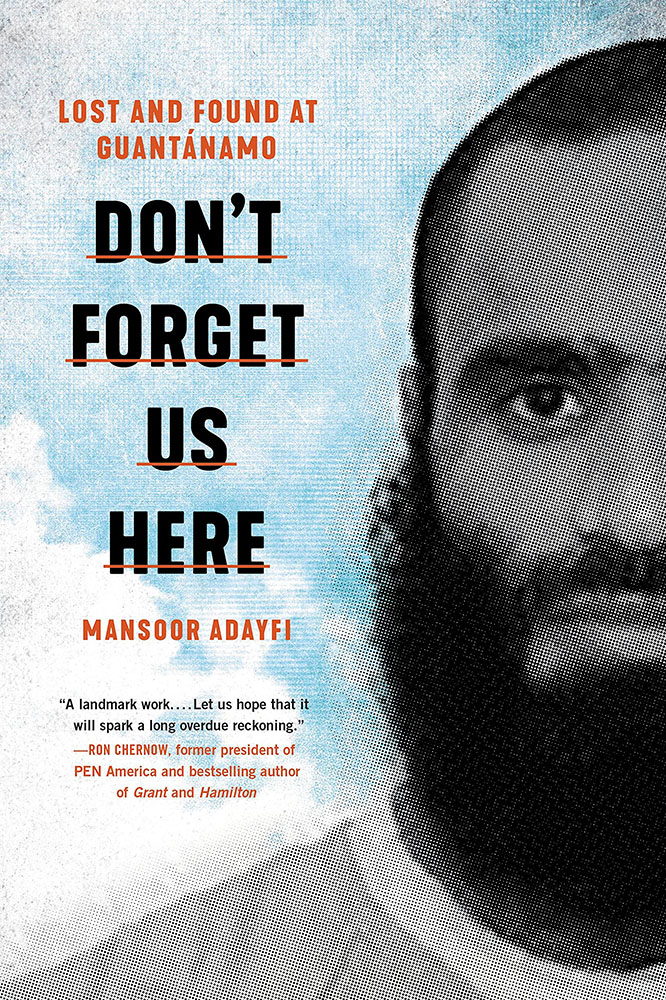

Don’t Forget Us Here, a memoir by Mansoor Adayfi

Hachette Books, 2021

ISBN 9780306923869

Marian Janssen

I am grateful that this journal asked me to review Don’t Forget Us Here by Mansoor Adayfi. Had I not promised to do so, I fear I would have found it too disturbing to finish the harrowing story of young Adayfi, who spent almost half his life as a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay. The story of Guantánamo, or Gitmo for short, is well-known: shortly after the “War on Terror” began in response to the terrorist attacks on 9/11, the George W. Bush administration set up a prison camp for foreign terror suspects at the American naval base in Cuba. At Gitmo, CIA, NSA and US military officers and soldiers carried out atrocious acts of torture, flouting the Geneva Convention. Since then, fewer than ten of the almost eight hundred suspects have been convicted of war crimes. Adayfi was one of the innocents, sold by Afghan warlords to the Americans and locked up for fourteen years without a trial.

Every thirty pages or so, I had to put his heart-breaking, brutal book away, as the descriptions of the torture he had to undergo — the hooding, punching, kicking, yelling, pepper-spraying, the sexual humiliation, and the chaining — were relentless. The physical violence other men inflicted on him was exacerbated by psychological pain: solitary confinement, sleep deprivation, death threats, and the fear, always, that he would spend his whole life locked up in a cage, would never see his family again — or that every day might be his last.

When Adayfi was detained, he was not even twenty, full of zest for life, looking forward to a golden future as a university student in the United Arab Emirates. I could not but think of my only son, who is now around that age, living a peaceful life in the Netherlands, as every parent would think of their own children enduring such an ordeal.

Adayfi overcame the unthinkable. He endured because of his sense of justice and his sense of injustice. He managed to survive because he cared deeply for his fellow prisoners. In the inhuman conditions at Gitmo, where for years he had no contact with his mother, father, and sisters, the other detainees came to stand for family, for love and loyalty. They became his brothers.

Animals, too, helped him pull through. He felt connected in his soul to the cats, banana rats, and, particularly, an iguana, Princess, who kept him company. (The guards left Princess alone, because she was a protected animal, and “soldiers could get fined $10,000 for touching or harming iguanas. She had more rights and freedom than we did.”) Because Adaify, “Detainee 441,” was considered a troublemaker, he spent much of his time in isolation, condemned to a small cage without a view for up to 22 hours a day, tormented by extreme noise, light, darkness, cold or heat. An occasional glimpse of the sea, or, perhaps, just the sound of its rolling waves, opened his heart, made him realize his own humanity, despite the guards treating him and his brothers as less than animals. Adayfi even describes a “golden age” in prison, a period in which, using recycled cardboard, soap, and other minimal elements, they brightened up their cells with artificial flowers and other things of beauty. The most artistic and creative among them, Moath, even made “windows” so that in his locked cage there were virtual views of the outside, of a vast blue sea, a sunset, birds flying freely.

In his preface, Adayfi states that he hoped that by describing the “small moments of joy and beauty, of friendship and brotherhood, of hardship and the struggle to survive — all the moments that united us and bonded us — that I could maybe change the way people thought about Guantánamo.” But everything beautiful was taken away again, as most guards took an animalistic pleasure in tearing down the works of art the prisoners made. For Adayfi there was, however, always one rapture that remained, that reaffirmed his belief in his own humanity: his love for Allah. I am an atheist and find it impossible to truly understand the kind of deep belief that Adayfi lives — or, for that matter, the Catholicism that my own mother so fervently adhered to, or Buddhism, Hinduism, any religion. To admit that, despite myself, I sometimes felt irritated by the exalted ways Adayfi spoke of Islam and Allah, reveals my own ungodly pettiness. I am grateful, though, that Adayfi’s faith helped save him.

What also saved him is his bravery, his courage. Mansoor Adayfi’s incredible strength of mind helped him live through the gut-wrenching, stomach-turning, mind-blowing (I really do not have enough adjectives) cruelties he was subjected to by agents of the United States of America. He was, often, the one who incited his brothers to acts of resistance, no matter how small, to get the guards to treat them more humanely. Owning practically nothing apart from blankets or boxers, their acts of insurrection had to make do with what was at hand, so they ranged from spraying guards with water and urine to smearing themselves with feces. The prisoners combined the latter with the biggest and — for themselves — the most dangerous weapon they had: the hunger strike. For when they were covered in feces, the guards were far more weary of force-feeding them, which they used to do by chaining the prisoners to a chair and then forcing huge tubes down their noses: “No numbing spray. No lubricant. Raw rubber and metal sliced the inside of my nose and throat. Pain shot through my sinuses and I thought my head would explode. I screamed and tried to fight but I couldn’t move. My nose bled and bled, but the nurse wouldn’t stop. ‘Eat!’ the nurse yelled. ‘Eat!’”

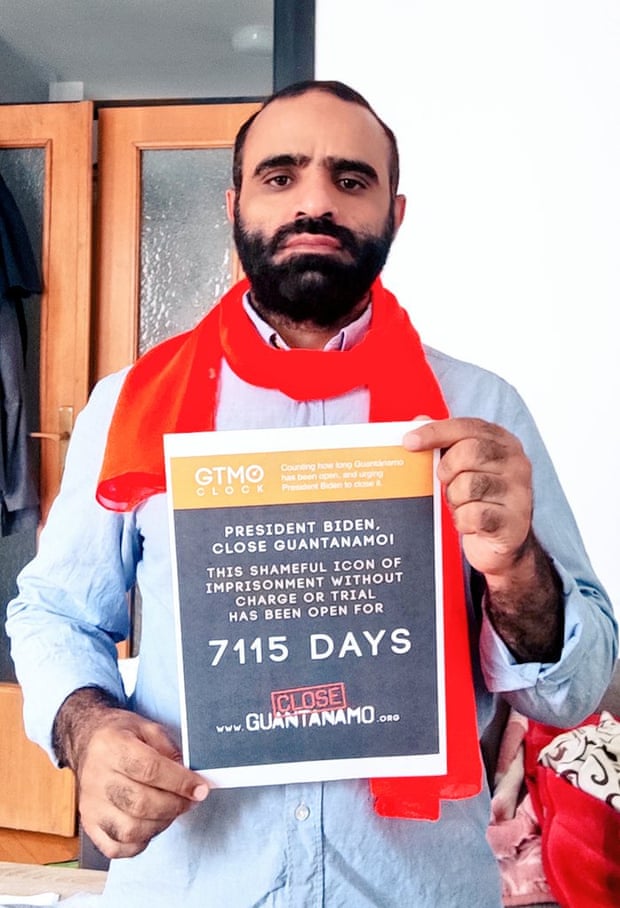

Hunger strikes sometimes led to just a little more freedom (although often the easing of the situation was soon reversed) and these small victories give some relief to this dark book, bring some light into the darkness that is Guantánamo Bay. Knowing that Adayfi survived this nightmare, I managed to read on, towards what I — still naively — hoped would be some sort of a happy end. I realized, of course, that, paradoxically, Adayfi himself never knew whether he would ever get out of this hell hole where he saw some of his brothers crippled, or murdered. But when Adayfi was finally allowed to leave, the end was no new beginning. He was not allowed to return to his family in his homeland, Yemen, but shipped off to Islamophobic Serbia in the same way he was shipped into Guantánamo Bay: “gagged, blindfolded, hooded, earmuffed, and shackled.”

I am still in shock. But everyone should read Don’t Forget Us Here. Spread the word, don’t forget the remaining detainees at Guantánamo Bay.

Mansoor Adayfi is a writer and former Guantánamo Bay Prison Camp detainee, held for over 14 years without charges as an enemy combatant. Adayfi was released to Serbia in 2016, where he struggles to make a new life for himself and to shed the designation of a suspected terrorist. Today, he is a writer and advocate with work published in the New York Times, including a column the Modern Love column “Taking Marriage Class at Guantánamo” and the op-ed “In Our Prison by the Sea.” He wrote the introduction, “Ode to the Sea: Art from Guantánamo Bay,” for the 2017-2018 exhibition of prisoners’ artwork at the John Jay College of Justice in New York City, and contributed to the scholarly volume, Witnessing Torture, published by Palgrave. In 2018, Adayfi participated in the creation of the award-winning radio documentary The Art of Now for BBC radio about art from Guantánamo and the CBC podcast Love Me, which aired on NPR’s Snap Judgment. Regularly interviewed by international news media about his experiences at Guantánamo and life after, he was also featured in Out of Gitmo, a mini-documentary and part of PBS’s Frontline series. Work from his memoir was recently featured at a public reading at the Edinburgh Book Festival along with work by Guantánamo Diary author Mohamedou Ould Slahi. His graphic narrative, Caged Lives, was by The Nib and will be included in the anthology Guantanamo Voices. In 2019, he won the Richard J. Margolis Award for nonfiction writers of social justice journalism.