An artist watching starvation in Gaza from afar befriends a fox in Abu Dhabi. Nature, the destroyer, also consoles.

It started with “the chair.” Work was seeping into the very fabric of my life like a dark stain spreading all over my world, eclipsing my days and nights, my suns and my moons. It was an overflowing cup of impossible deadlines and projects spilling out beyond their 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., flooding my days, leaving me scrambling to find dry ground. The relentless routine was killing me.

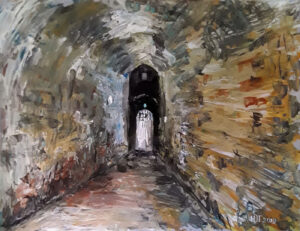

I yearned for change, adventure, movement, freedom. So I signed up for the Women’s Heritage Walk, a 150 km walk over five days from Al Ain to Abu Dhabi through the desert. Training for the walk was intense and I threw myself into it with a vengeance and determination I didn’t know I had. I loved the challenge and being outdoors in the wilderness of the dunes. After I completed the walk in 2017, walking became part of my DNA.

I started waking up around 5 a.m. to squeeze in an hour’s walk in the golf club by my house before facing the tornado of my working day. I went to the trees, the grass, the birds, and watched the sun rise. It became a daily morning meditation, a pilgrimage even that prepared me for the day ahead.

To relieve stress at work, I turned my office into a mini art studio, and doodled in my breaks. But, unlike mindless office doodling, my cursory drawings were made on tiny scraps of canvas that I hid beneath my keyboard. One day, I drew a chair floating against a backdrop of repeating lines and spirals. I wrote poems about the chair. I painted the chair in my studio at home.

The chair became the symbol of the confinement I felt, the clocking in and out of work, the increasingly regular trespassing of my employment on my weekends and summer holidays, the reserved performance appraisal at yearend that always made me feel as though I hadn’t done enough. It was the bureaucracy of everything, the policies and procedures, and approvals and the long, long hours of just sitting in the chair I had come to loathe.

The longer I sat in the chair, the more I walked and the more I challenged myself. I never let the harshness of Abu Dhabi’s weather — the intense heat and suffocating humidity — stop me from reaching an average of 20,000 steps per day. The golf club near my home became my forest of sanctuary, an extension of my art studio, my own personal playground. The trees were always there, waiting for me, patiently. And I waited for the day when I could walk away from the chair once and for all. That day came on June 23, 2023 when I was released from captivity back into the wild!

I make up for all the hours in the chair by spending most of my day outside. My senses have been reawakened. On my walks I notice every little detail of the natural world around me: the rock formations that line the paths along the fairways, the bird footprints in the sand, the trees and their shifting shadows, and in the distance the unmistakable black silhouette of an Arabian fox in the grey predawn light.

From just a distant shadow, a blurry image on my camera, she began over the weeks to show growing curiosity and came more into focus into my landscape. She was following me as I followed her. She observed me just as much as I was observing her. I guess she decided I could be trusted. One day she trotted up to me on the path and sniffed my shoes. I named her Blue after my favorite color and because she has a small bluish scar on her nose.

When I posted a video of our first interactions together on Instagram, my inbox was flooded with questions from people asking me where I was. They could not believe foxes exist in the UAE. In fact, Arabian red foxes, Vulpes vulpes arabica, is a smaller subspecies of the red fox native to the Arabian Peninsula. These animals have been living in this part of the world for thousands of years, evolving and adapting to the desert environment and the rapid urbanization the Emirates have undergone in the last 50 years. The foxes have learned to not only survive but to thrive in cities like Dubai and Abu Dhabi and they are not considered endangered. They are smaller than their European counterparts but their ears are much larger to dissipate heat and detect prey underground. As omnivores, they eat rodents, insects, and reptiles but they also eat fruits and plants and leftovers from human meals.

On my walks I notice every little detail of the natural world around me: the rock formations that line the paths along the fairways, the bird footprints in the sand, the trees and their shifting shadows, and in the distance the unmistakable black silhouette of an Arabian fox in the grey predawn light.

Blue is a beautiful creature. Her fur is a warm brown with hues of auburn, the same shade as the dry grass on the hill that has become our meeting place. Her cheeks and the tip of her tail are white. Her wide almond shaped eyes slant slightly upwards and fluctuate, depending on the light, from amber to a greenish yellow.

She is nocturnal, which is why I only find her around sunrise and sunset. During the day she hides in one of the many dens scattered around her territory. Once I saw her dig a den in the midst of a dense thorny thicket. She expertly excavated the soft sand with her slim long muscular legs before she disappeared beneath the ground. She then emerged to shake herself off and start digging again.

I watched her use those same legs to climb a tall tree, balancing herself like a trapeze artist on the high thin branches. I held my breath below, craning my neck to watch her, zooming in on my camera to capture her stunt while praying that she does not fall and injure herself.

I was addicted to being in her presence. I felt both energized and privileged to be allowed to watch her so closely. Most of what I have learned about her has been done by observation. She loves eggs, dates, and corn on the cob that I carry in the small pouch I wear around my waist. She especially likes eggs. Her tongue comes out in a little instinctive lick when she sees one. She does not like apples or peaches. When I offer them to her, she urinates on them and walks away. She’ll often take the dates I give her and bury them in the ground, using her nose to cover them meticulously with sand and then sprinkling a few drops of her scent for later location for when she’s hungry. Actually, she sprays her scent every few seconds as she moves through her terrain. She even doused my unattended coffee mug I had left on the ground, while trying to photograph her.

With every new interaction with Blue, I wanted to know more. During online research I came across an article about Rob Gubiani, a photographer and conservation advocate in Abu Dhabi who had followed a fox for six months. I tracked him down, and via a Zoom call we exchanged stories.

I take a beautiful close-up of Blue with the egg in her mouth and I share a story on Instagram. It might show a fox, but the photograph is about Palestine. It is my small attempt to crack the mighty algorithm and resist, from the shadows.

I learned that foxes tend to live in groups consisting of a mated pair and their offspring. A couple of months into our relationship, Blue introduced me to her “family,” a female — I call Red— and a male, I named Cheeks. These two had been consistently lurking in the background, watching Blue and me. In time they too decided to trust me though not as fully as Blue does. Eventually I became part of a tribe of wild foxes. Each of them have their own personality, and although I have no way of knowing this, I have a theory that Blue might be the daughter of Red and Cheeks. I will never know how old Blue is but I do know that she can live to the age of twelve. I cannot bear the idea of her not living.

To let her know I’m around I make a sound — “psstpsst”— and wait for the rustling leaves that signal her approach. Nowadays, Blue, Red, and Cheeks arrive from different directions, surrounding and circling me. Cheeks is the alpha male, often showing his dominance by trying to chase the females away so he can have any treats I brought all to himself. I have to think like a fox and have become quite sly at times, distracting Cheeks with a date while I slip an egg behind my back to Blue. Foxes do not share food!

Blue and Red are very playful. Blue usually begins playing by sneaking up on Red and pouncing on her. I have caught on video some magical moments of the wrestling fun these two females have while Cheeks, who I sense is older, rests in the shade of a distant tree.

After they eat and play, Blue and Red go hunting. They prowl the grounds through the thick layer of fallen leaves, their ears perk up as they listen for prey underneath. I have seen Blue jump and land on all four paws for maximum impact, to kill whatever lies beneath her feet. I have watched her head disappear beneath the dry leaves only to come out with a wriggling lizard in her mouth. I have heard the crunch of its bones beneath her teeth. When I am with my fox tribe my senses are on full alert. My eyes analyze their body language in anticipation of something amazing. My ears listen out for their low growls and the strange clicking sound they make at each other when they are in attack mode. I hold my professional camera in one hand and the phone in the other, often filming and photographing simultaneously so I don’t miss a thing, especially from Blue, my little daredevil. I wonder sometimes what made her come to me that day in December, just before my 49th birthday. Did she sense that I needed her in my life?

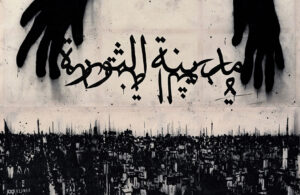

2024 was an emotional year and 2025 even more so. The golf course, my sanctuary, was permanently closed at the start of the year. I watched it turn from an oasis to a barren landscape as I watched Gaza be transformed into an apocalyptic wasteland. I know about war from my childhood in Lebanon, where I am from originally. The scenes of horror coming out of Gaza brought back terrible memories I have of hiding from the bombing in makeshift shelters, of displacement and constant fear. My entire belief system crumbled as the world around me grew darker and darker. To deal with the overwhelming feelings of rage, disbelief, hopelessness and helplessness, and to resist the numbness that was overtaking me, I turned to art, poetry, and nature. The chair began to appear again in my painfully colorful paintings and drawings of Gaza, a brutally minimalist symbol of the whole world watching the genocide. I refused to be a chair. In my poems I screamed in protest against injustice, everywhere.

I desperately wanted to find some hope amidst the desolation spreading inside me.

Blue is that light. She represents everything that is still honest and pure and real and free in the world. When I sit with her while she delicately pierces a hole in an egg so she can suck the white and yolk through the shell without spilling a drop, I am filled with awe. For a few seconds I forget an image that is always with me, of starving children in Gaza picking over spilled flour from the street as they cry in hunger and despair. I take a beautiful close-up of Blue with the egg in her mouth and I share a story on Instagram. It might show a fox, but the photograph is about Palestine. It is my small attempt to crack the mighty algorithm and resist, from the shadows.

Blue has watched me build, over several weeks, 77 sculptures out of bricks that I have found along the broken pathways of the old golf course. As I have been doing it I speak to her. I tell her about people waiting 77 years for freedom and justice. And when my unofficial sculptural installation is complete and she strolls amongst the eastward facing figures I created, posing for my brand new camera — I bought specifically for her — I can feel a light flickering inside me that resembles hope and optimism. I make a reel and post it with a caption that reads, “waiting for the sun.”

When Blue allowed me into her world, she gave me a new voice, a new way of seeing, thinking, and dreaming. I love her and am so grateful for her existence in my life.

Most days, after my visit with Blue, I head to Saadiyat Beach, another haven I have been retreating to for many years and it is where I sit and write these very words. Here I find a sand canvas that stretches for kilometers along the Arabian sea. I keep a rake here, in the same way I keep brushes and crayons in my studio. When the tide is low, I use the rake to draw whatever is in my heart: dreams, hopes, prayers, fears, forbidden words, watermelons, or just endless spirals swirling outwards towards the water and the sun.

And as the tide slowly rises, the waves gently remove everything I have created and carry it out towards the horizon where the sky is always waiting but not always blue.