I had intended my poetry to be a kind of salvation for me in my confrontation with the onslaught of a perpetually antagonistic world. When this confrontation failed, I tried convincing myself that surrendering to the world — being a scrap of paper floating downriver — was the only salvation available to me. But this proved impossible, too. —Wadih Saadeh

A Horse at the Door, poems by Wadih Saadeh, translated by Robin Moger

Tenement Press 2024

ISBN 9781917304023

Alex Tan

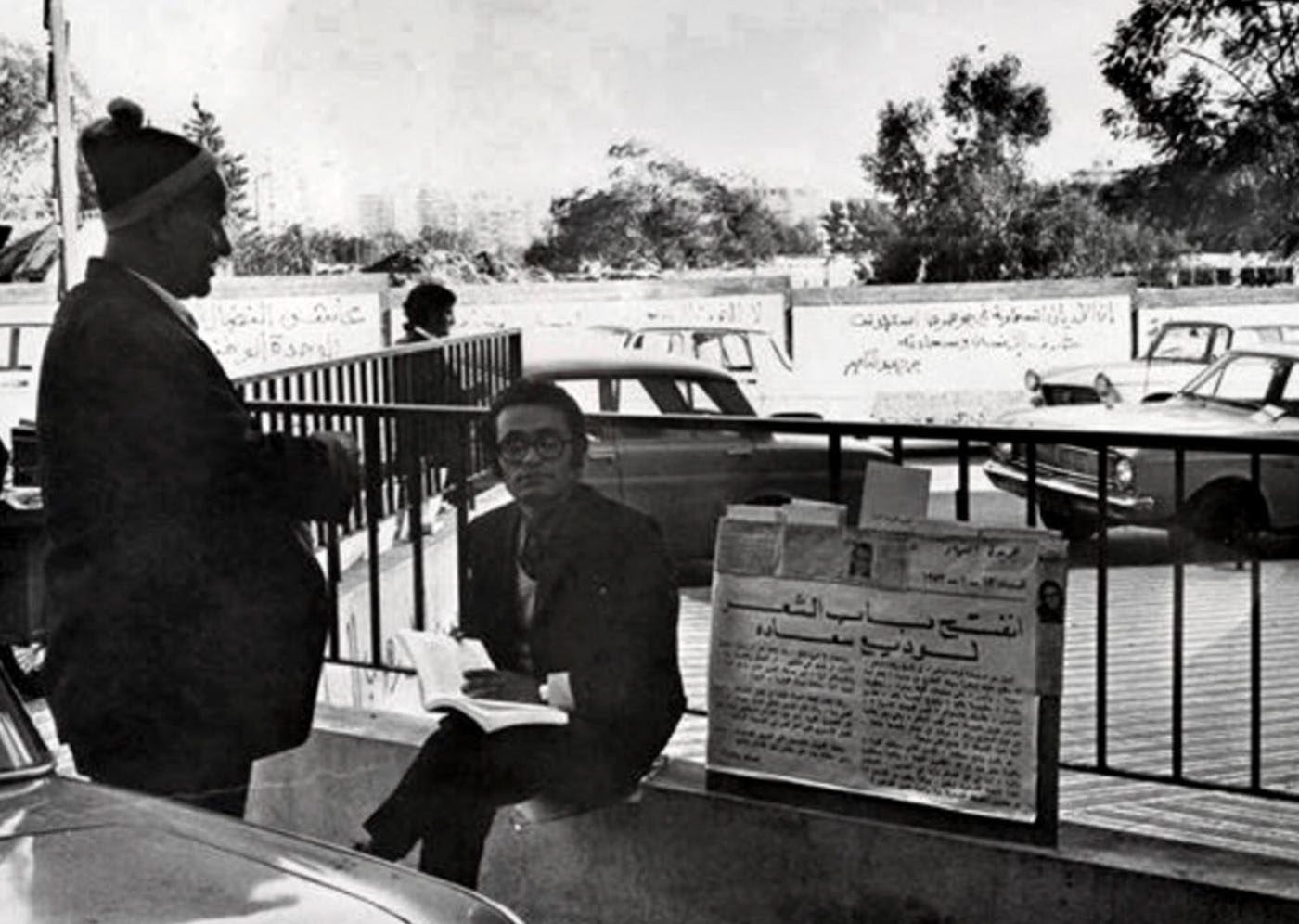

There is a famous image of the Lebanese-Australian poet Wadih Saadeh selling his handwritten poems on Hamra Street in pre-civil war Beirut — what he calls, in an autobiographical prose poem, the “refuge” of “all the Arab dreams” of the time. He sits cross-legged with a book spread open on his lap, turning an unconcerned glance toward the camera. Beside him lie stacks of his work, with a sign that reads: “The door of poetry has opened.” Huda Fakhreddine, in The Arabic Prose Poem, begins her chapter on Saadeh with this anecdote to outline the unmediated relation that the poet sought with his readers, sidestepping traditional networks of publishing and marketing. Even today, Saadeh continues to make his poetry freely available on his Facebook page.

That openness might be surprising for a writer of his stature — Mahmoud Darwish called Saadeh’s Because of a Cloud, Most Probably “one of the most important collections of poetry” he had read in recent years, and Youssef Rakha termed him “very arguably the greatest living Arabic poet.” But his lack of ostentation makes perfect sense — and indeed appears all the more admirable — when juxtaposed with his writing, which is distinguished by its indifference toward the earthly and the ornamental, and by its restless refusal of fixity. Life and art correspond with a rare closeness: before settling in Australia as an émigré, his life was one of perpetual wandering, through such cities as Beirut, Paris, London, and Nicosia. Even in the history of Arabic prose poetry, in which Saadeh occupies an essential place, he represents something of an outsider. In the fifties and sixties, his contemporaries Adonis and Unsi al-Hajj were penning oppositional treatises that self-consciously deviated from a tradition of sedimented poetic form — governed by fixed rules of meter and mono-rhyme that had remained virtually unchanged since their origination in the pre-Islamic era. Unlike them, Saadeh preferred to write as if unbound by that weight — as if already free. In this, he heeded the advice of his friend, the influential Iraqi poet Sargon Boulos, who once wrote to him in a letter, “Don’t be an intellectual who accumulates masks and reads famous writers (…) Have you ever thought for a moment how amusing it is to ‘be’ something?”

Given Saadeh’s eminence in the Arabophone world, Tenement Press’s publication of A Horse at the Door is long overdue. Ranged in this collection — or “chronology,” as the cover would have it — are intricately curated selections from Saadeh’s three-decade-long oeuvre. Translated with exquisite attention by Robin Moger, whose grasp of a writer’s idiom is always exceptionally attuned, the poems offer us glimpses into a mind whose preoccupations dwell in the evanescent and the gestural. They are a mix of brief, orphic riddles and protracted, meditative meanderings; through them Saadeh elaborates an iconographic universe all his own. The book is beautiful, too, as an object; several of the longer poems — including the famed “Seat of a Passenger Who Left the Bus,” which Youssef Rakha compares to Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” — are typeset vertically, the words rising like smoke from the ground to the sky. The reader must rotate the book 90 degrees, effecting a shift in orientation for the lines to be legible, almost as if floating through a dream.

Read in isolation, his shorter vignettes — often spanning no more than a handful of lines — appear as gnomic parables. Personas, almost always male, are seized in the midst of sitting on porches, departing from houses, clipping a sunbeam. Often, they are dead, awaiting discovery, “vivid with blood and dust,” yet somehow retaining a sentient alertness to the world. In Saadeh’s metaphysics, it seems, death represents but a threshold, an entrance into another realm. It has a basis, perhaps, in Saadeh’s own experience; when he was fourteen, he lost his father to a house fire, witnessing the charred corpse being borne away by mourners. “Too young to lift the dead, I bore him, as they carried him, in my eyes,” he writes. Is it guilt that compels the poet to return, later in life, to the wound of an originary trauma, and to death writ large? One narrator measures his own mortification: “I am dead enough and I have the time to weave dreams. Dead enough to devise the life I want.” A different kind of speaking becomes possible from beyond the grave, a roomy vantage point from which life itself, in all its incompletion, might be approached as the illusion it really is.

Perhaps Saadeh’s body of work sublimates, in textual form, the law of conservation: nothing can be created or destroyed, only rearranged in space and transfigured in shape. Bodies and objects in A Horse at the Door, susceptible to perpetual metamorphosis, manifest a primordial continuity with the natural world. A palm holding salt might have been an ocean in the past, its materiality mapped onto a more boundless geography. A man who touches a shoot he’s planted has “sap run from his hand into its veins”; “leaves went from his eyes onto its branches,” as if the act of care for another being has wrought a transformation of his substance into vegetable matter. Someone who drowns “became a cloud” and “fell in drops,” so that swimmers now “swim in him.” Indeed, many of the poems forge, from this enmeshment of past lives and reincarnations, an argument against being reckless or callous with the things in our proximity, lest they harbor the atoms of a beloved. Addressing himself as “Wadih,” Saadeh issues injunctions to “throw nothing away (…) The thing you throw may be a friend who wants to stay, may be a mouth that longs to speak with you.”

That shift from “a friend” to “a mouth,” from the whole to the part, enacts a disclosure of truth in the movement towards metonymy. Clairvoyant of the small — the epithet that W.G. Sebald lent to Swiss modernist Robert Walser — might be Saadeh’s title. It is characteristic of his outlook that the fragmented, the minute, and the fallen refract something much more profound and integral than might any fantasy of prelapsarian unity. Entirety, as such, divulges itself most lucidly in its very disintegration, as in “Someone in the Ashes”: “As they burned the body / he saw him, all of him, in the smoke (…) and when those ashes had been a body / he had seen nothing.” Loss becomes a precondition for vision. And this totality, fugitively apprehended, is not just a corporeal likeness — a Celanian assemblage of “a hand, a mouth, an eye” — but also an abbreviated biography, a life flashing before the eyes: from “being born from his mother’s womb” to “his figure lost / amid the laborers stampeding through the streets.” If there is a revolutionary undertow to Saadeh’s writing, it surges in snatches of memory and desire, indistinctly conjured.

How poignant, too, that insight into a spontaneous formation of collectivity arises behind a smokescreen, emanating from the evaporation of flesh. Smoke — that most obfuscating of elements — turns into a privileged medium of clarity. It is precisely this gesture of Saadeh’s that testifies to the dialectical inversions structuring his cosmology. Alongside smoke, dust, clouds, soil, and other amalgamations of particulate matter are elevated; in their fragility, their tendency toward dissipation, he locates a kind of endurance. “For me to be present in life, I must first be present in death,” he once said in an interview. Shadows linger, ironically, as inscriptions of permanence, persisting beyond the departure of their person. Marilynne Robinson’s sublime and melancholy Housekeeping, with its fixation on abandonment, comes to mind: “But if she lost me, I would become extraordinary by my vanishing.” Such a philosophy of eternal passage marks, for the poet, a way to mourn and to hold on. It is, more fundamentally, a disavowal of the trappings that coordinate one’s personhood within a matrix of worldly recognition: Saadeh’s figures tend to be stripped of property and possession, name and nationhood, wandering without end.

Robin Moger’s perceptiveness toward Saadeh’s dialectics is everywhere apparent in his acutely rendered translations, but one luminous moment shines through. From the poem “Of Dust”: “The earth is nothing like us. It is our antithesis; we are its debris.” The original Arabic reads:

ما كان الأرض لا يشبهنا. إنه نقيضنا ونحن أنقاضه.

The combination of naqīḍ (“antithesis”) and anqāḍ (“debris”) in the same line recalls the paronomasia of classical Arabic poetry, in which words derived from the same root, sometimes with vastly differing meanings, are trotted out in proximity to one another. Here, naqīḍ and anqāḍ stem from the trilateral root nqḍ, which carries the sense of destroying, annulling, and undoing. Moger has cleverly preserved the typographical rhyme by selecting the pair “antithesis” and “debris,” even as the silent “s” at the end of “debris” gives the lie to that sonic affinity, breaking the pact of association. Fractured between eye and ear, Moger’s English undoes itself, almost like a metaphor for Saadeh’s wider project.

While much of Saadeh’s oeuvre seems haloed by an air of universality — his later work, in particular, reads like thought experiments, staging grounds for distilled aphorisms and propositions — it is not without a politics. Sometimes, it is by means of these wavering images, hovering on the fringe of unreality, that the poems articulate a feeling of haunting unrest. In the longer poem, “Dead Moments,” massing clouds are likened to “the breath of the migrants” while horrific massacres rage on outside. Seldom does war enter directly into Saadeh’s poetry, but here it is suffocatingly close; the names of the dead and wounded are enumerated on the radio, the specters of deceased friends hang on the windowpane, and dismembered limbs are scattered on the streets. As the first-person speaker wonders at his own intact body, unable to fathom his survival, the rest of the collection — with its proliferation of disembodied organs and wholenesses undone — is thrown into relief.

Each subsequent attempt at reconstitution trails behind the literality of the carnage, the enormity of impossible mourning. “How great the span from rib to rib,” one speaker laments, failing to congeal a friend dissolved in the water; another nameless being, whose pieces are scattered everywhere, tries “in vain to gather his parts together.” Through their splintering and damage, these creatures constitute a symptom of history’s failures. “We walk carrying our bodies,” writes Saadeh elsewhere in a more explicitly autobiographical poem about the Lebanese Civil War, “in soft skins that survived the wars.” As if to teach us what this means, yet another circuitous piece (composed a decade later) speculates, “Sometimes I have a feeling that humans live without a body (…) when they despair of finding it, they die.”

Split between subjectivity and its embodiment, between interiority and the flesh that would enfold it, A Horse at the Door instead imbues individual hands, feet, and eyes with a brimming animacy. Against a backdrop where bodily integrity cannot be taken for granted — where maiming is a strategy calculated to incapacitate populations — he finds, in his own corporeal form, the potential for friendship and loyalty: “Foot, so strangely devoted that it never parted company from me….” Yet most distinctive in Saadeh’s signature might be the tenderness and solidity he lends to their imprints: “words and breaths and glances” can detach from their “owners” and assume autonomous afterlives of their own. Conversely, “those we look at enter our bodies through our eyes and become flesh and blood.” Thus sense-impressions, incorporated into the self on a cellular scale, become a channel through which the poet recuperates the ancestral. Etel Adnan’s line comes to mind: “Love begins with the awareness of the curve of a back, the length of an eyebrow, the beginning of a smile.” Elemental gestures of speaking and looking, Saadeh never ceases to remind us, are portals through which we receive the presence of another.

Hospitality, then, might be one password to Saadeh’s ciphers. He honors every encounter by bestowing a sensuous reality upon otherwise invisible properties, concepts, states of being (“he was breathing not the air / but their passing”). He is obsessed with metaphors of space and spatiality, with the sites in which one might host these temporary inhabitants, whatever shape they take. Often, they are exhausted vagrants and sojourners, searching for a place in which to pause — to sit. The action of sitting, along with its complement walking, takes on an outsized importance in Saadeh’s lexicon: “Walk / and wait for the eye of one passing to look your way, that you might sit in it and rest.” In a similar vein, he bemoans that “glances have no place to be,” that they may be “orphaned in the void.” Everything hungers for a home, searches for the manner in which it can dwell in the world. Hearts are “shores / on which lie souls sprawled and drowsing”; the mind is a “garden” that “holds fruits”; the breath might unfurl into a “road.” It is Saadeh’s way of loving that which exceeds him, from the exposed nerve-ending of the self.

Over the course of A Horse at the Door, these architectures of shelter and itinerancy piece together a topography that, through the iterativeness of its images, accommodates and adjusts itself to the contours of the reader’s mind. It might be the reader, in her absence and alterity, who is addressed when the poet writes, in the transcendent “The Beauty of Those Passing”: “The most beautiful among us is the one who forsakes his presence, who leaves a clean space by vacating his seat, a beauty in the air by his voice’s absence, a clarity in the soil left uncultivated. The most beautiful among us: the absent.”

If reading can be personified in the same way that gazing, breathing and passing-through are gifted with vitality, then it is our readership — that suspension of the self, that provisional voiding of identity and desire, that silence in which we might listen for the voices of the extinguished — it is our readership, above all, for which Saadeh’s poetry prepares a seat, and opens a door.