Malu Halasa

Mana Neyestani, a noted Iranian editorial cartoonist and author of graphic novels, is aware of the limitations of telling a story in a single drawing. “In a cartoon,” he once said, “there isn’t enough time for in-depth characterization.”

He turned to the graphic novel after his 2006 arrest in Iran and imprisonment in Evin Prison. His first, An Iranian Metamorphosis, was published in 2012, after he left Iran and settled in France. His most recent graphic novel, Les Oiseaux De Papier [The Paper Birds], has been published in French and reviewed here by Clive Bell.

For this TMR conversation, the cartoonist reveals the working practices of his day, and where the ideas for his graphic novels come from. It’s one thing to be a satirical artist in your home country, quite another gauging the temperature of a place from afar. There is an enormous pressure on artists in the diaspora to be authentic and true to “home.” Yet, Neyestani is no stranger to the deep and secret undercurrents of his country. His cartoons and novels have emerged as a barometer of the highs and lows of modern Iran as well as the stories of the people living there.

Malu Halasa: What time do you wake up? After breakfast do you go straight to your desk, and start drawing? Or are you a night owl and work better late at night?

Mana Neyestani: I usually get up at nine o’clock in the morning, I’m not so disciplined with ironclad rules. Sometimes when I get up in the morning, my brain engine doesn’t work. I need to spend some time, chat with friends, and drink tea or coffee to gradually feel like working. I do not have to punch my timesheet at a certain time; I’m not anyone’s employee. I’m supposed to draw one or two things during the day. I may finish the work at 12 noon or eight at night. It depends on my mood and brain. Sometimes I draw three works in one day. Sometimes I don’t feel like working a whole day, but if there’s a deadline to deliver a work, I will definitely deliver it on time. If I work on a graphic novel, for example, I set a timeframe for myself to finish a certain number of pages in a month. One day I might do only one page and the other day three pages, but on the whole they should be ready by the deadline. Whenever I’m in a good mood, I work more to make up for the coming days when I might not be in such good shape.

TMR: You once admitted that newspapers and websites spark ideas about editorial cartoons. What newspapers and websites and social media are you looking at? And do you go to the same sources for ideas for your graphic novels?

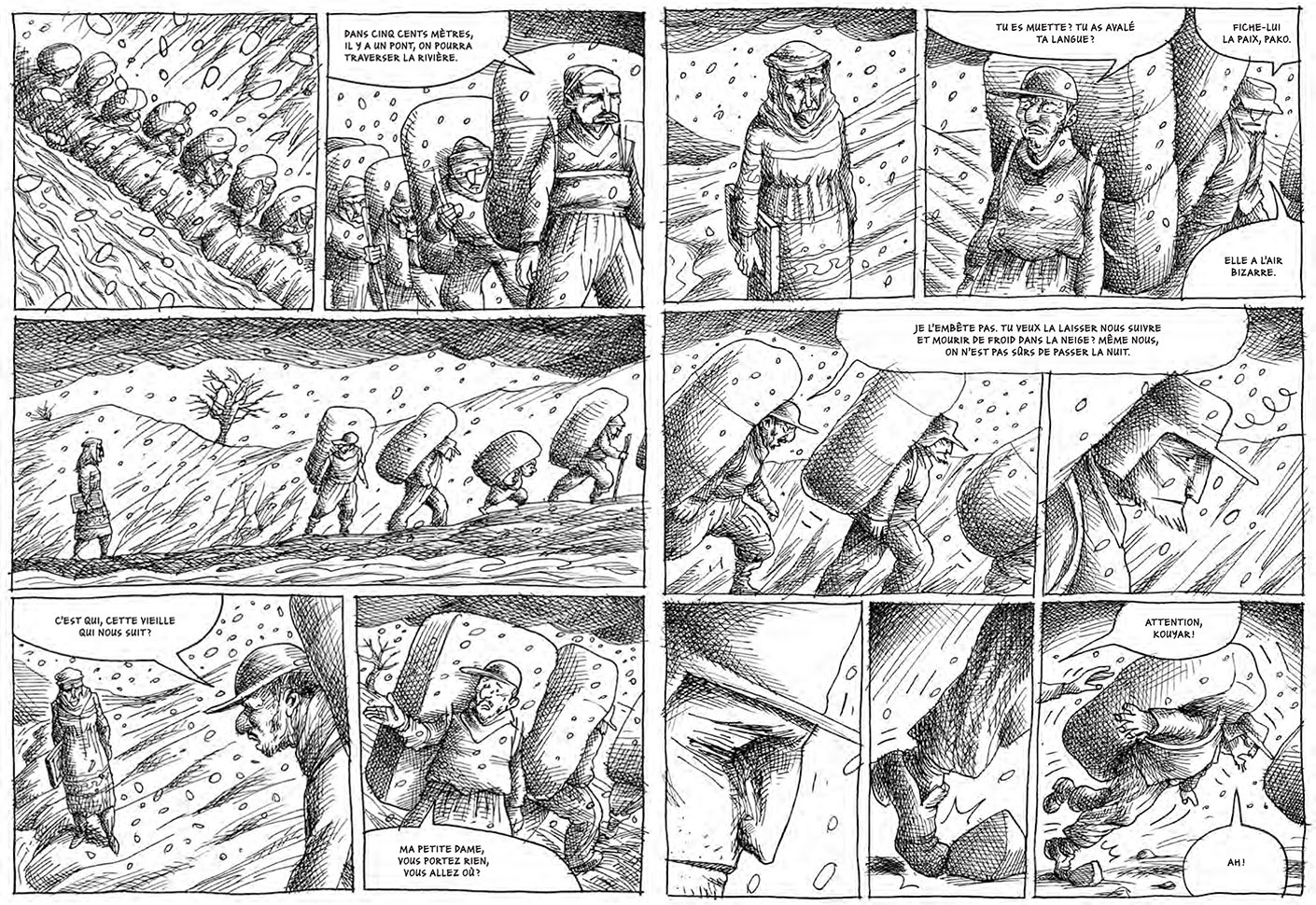

Mana Neyestani: I look at Persian-language media abroad and pages of my friends who are active on Twitter and Instagram and have first-hand news, especially journalist friends. But my preference is to first look at the news which is confirmed by the Persian-language media outside the country. IranWire, Iran International TV, Radio Farda, Deutsche Welle Persian … are some of those news outlets. For a graphic novel, it is slightly different. It depends on the story I’m working on. In books such as Mashhad’s Spider or Paper Birds, I try to turn rigid headlines in the media into a human and tangible narrative for the reading audience. For example, the headlines are: 16 street women [prostitutes] were strangled by a fanatical, religious killer, or, 6 kolbars [Kurdish porters] died in the snow during a trip through the highlands of Kurdistan, or were shot by border guards. Of course, reading these headlines is painful, but the media and news headlines strangely turn people into numbers. When you tell a story about a deadly kolbar journey, you have the opportunity to turn these figures into flesh and blood; human beings with human weaknesses and strengths and palpable emotions that can be easily wiped off the face of time, due to unfair conditions. When you write a story, you have the opportunity to tell about the dreams and wishes of those murdered street women, or even about the fears and pains of their murderer, without justifying his actions.

TMR: Do you keep to a strict schedule at your desk? For example, do you work for two or three hours, take a break and come back or stay at your desk all day long? If you do take a break, what do you do in the break, take a walk, or wash dishes?

Mana Neyestani: As I mentioned earlier, since I work at home, I don’t have a limited schedule, so I have to set this limit myself. I decide to work on a certain number of drawings in one day (for example, two sketches and three pencil pages of a book.) They should be finished by nine at night. But I don’t insist on working for three hours in a row. I may or may not do anything for the whole morning. In the middle of work, I may leave for two or three hours, go out to eat, chat with friends, take a walk, and drink coffee. For example, now, I have stopped working and I’m answering these questions!

TMR: Where did your idea for your graphic novel The Paper Birds come from? And what are the inspirations for the drawings? Do you look at photographs or other visual images to motivate the artistic, drawing side of your imagination?

Mana Neyestani: In the past two decades, there has been a lot of news about kolbars, along with impressive images and clips — news about kolbars being shot by the regime’s agents; or being killed by avalanches, floods, freezing conditions, and other disasters; reports about the hardships of their job; their social and financial situation. However, no positive change has occurred in their situation. I worked on some editorial cartoons about the kolbars based on these news and events. Almost five years ago, I decided to make kolbars the subject of a graphic novel; it would both bring them into the spotlight and provide dynamic and attractive material for illustration. I based it on many pictures and clips that I had seen, including the story of two teenage kolbars who were frozen to death a few years ago, as well as an interesting video report made by BBC Persian reporters about kolbars. At the same time, I contacted one or two Kurdish kolbars who were in social media, such as Instagram, and asked them questions. Not only about the trip itself, but about their lifestyle and daily routine, to understand them better. Then I started to imagine the moments and scenes that I would like to see in my book, including the concept of “load” becoming a villain and a monster with whom the old kolbar is wrestling with — just like a mythical battle. Then slowly I shaped and made the story.

The inspiration for my editorial cartoons about Iran is naturally the images that are broadcast on virtual networks.

TMR: Graphic novels are different from editorial cartoons, in a graphic novel you’re telling a longer, more dramatic story. Do you know the story before you start drawing it and writing it, or are you the kind of writer who only knows the story once you start drawing and writing? What is the creative process? Do you work from an outline or at the beginning is it a free-for-all?

Mana Neyestani: For a graphic novel, you must have a specific and clear storyline structure. I am not in the habit of writing a detailed and complete script and then start illustrating, but I write an outline of ten or 20 pages along with some dialogues that I find interesting. These may change in the course of the work because there is always a possibility that interesting story ideas will come to my mind during the work. I like this sort of improvisation within the framework of the main structure of the story.

Unfortunately, I’m not skilled enough to be able to draw a novel graphic page without an initial pencil design and draw it as a completely freehand sketch, so I definitely need to prepare a pencil base first and then ink it. However, sometimes the pencil drawing is so messy and scribbled that only I can understand which line is the main one and should be inked.

TMR: Do you already have the idea for your next graphic novel?

Mana Neyestani: I’m working on a part of Marjane Satrapi’s upcoming book about the Woman, Life, Freedom revolution. This project is a joint work of many artists from different countries, including Iran, and I’m responsible for a small part of it. Then, we have a joint work with two other Iranian artists about the Ukrainian International Airlines Flight 752, which was shot down in 2020 by missiles fired by the Revolutionary Guards, with missiles, and the death of our mutual friend, who was on the plane. We will recount the trauma of the crash of that plane as a work by three people.

For an individual project, I have the idea of a fictional work about a refugee cartoonist in France who has reached the end of the line and is about to commit suicide, and a terrorist group suggests that he carry out a suicide attack to blow up the Eiffel Tower. It will probably be dark humor, and if my publisher agrees to publish it, I will complete the story. I haven’t told him the idea yet!

TMR: France is the home of bandes dessinées, are you writing your graphic novels for French readers or for Iranian readers? Or it doesn’t matter which the audience reads your work?

Mana Neyestani: First of all, I write and draw so that I, myself, can enjoy telling the story, but I know that a non-Iranian audience is also going to read it, so I avoid hard hints and vague references that only have meaning for Iranians. The second thing is the publisher who reads the work [though the eyes of ] a French audience. If something is still unclear, he asks me to correct it. We know many of the details, but a non-Iranian audience needs more explanation to understand a story or situation.

TMR: Do you press yourself to work until you can’t work any longer, or do you aim to stop at a particular time?

Mana Neyestani: As a matter of fact, today at lunch in a French cafe, I saw an elderly customer whose hands were shaking so much that he couldn’t even hold a spoon properly, so I asked myself the same question. I live day by day. Hopefully I’ll be done before I get Parkinson’s or lose my sight or lose my ability to work somehow.

TMR: When do you finish your working day? What do you do to relax?

Mana Neyestani: It doesn’t have to be a specific time. I usually don’t work after nine in the evening. I sit and watch a series or movie with my wife. Sometimes I drink. We go to the cinema on weekends.

TMR: Who are your favorite authors of bandes dessinées?

Mana Neyestani: I still love the power of storytelling and characterization of Herge, the author of Tintin. Alan Moore is also amazing in Watchmen. and Frank Miller in the Sin City series. I also like Satrapi’s book Chicken with Plums. She has combined humor and sadness in a Thousand and one Nights style story.

Translated from the Persian by Farrokh Hessamian.