Select Other Languages French.

Empty Cages illustrates that the female subject isn't just formed through being desired; she is also shaped by moments of refusal, reversal, and the weight of inherited shame. The body becomes a battleground, where dignity and collapse struggle for dominance.

Empty Cages, a novel by Fatma Qandil

AUC Press 2025

ISBN 9781649033208

A mother and her daughter sit together in their garden in 1960s Cairo. The daughter begins school the following morning, her first day ever. The mother gently warns her not to let anyone touch her body. The girl giggles and recounts a memory: When she was four, she would visit their young neighbor, who was a university student, lie beside him, and they would explore each other’s bodies. Decades later, the daughter, now in her sixties, will remember and write, “I didn’t feel ashamed or upset. He was kind and sweet.” But this wasn’t the mother’s reaction when she heard the story for the first time; her mother trembled, cursed the boy, and vowed to kill him. Undeterred, the daughter continues: Auntie Fatima, who helped around the house, would take her into the bedroom and touch her, too. As her mother nears a heart attack, the girl keeps giggling, insisting she enjoyed it.

This scene originates from Empty Cages, a novel recently published by AUC Press, and translated by Adam Talib. The Arabic book won the prestigious Naguib Mahfouz Medal Prize for Literature in the novel category. However, many readers approached it as if it were a memoir, or at the very least, an autofiction by Fatma Qandil — a poet, critic, literary provocateur, and professor of modern literary criticism at Helwan University’s Faculty of Arts.

Qandil is best known for her poetry. Her collections, The Silence of Wet Cotton (1995) and Means Hanging Like Slaughtered Animals (2008), are considered milestones in contemporary Arabic literature, their influence visible across a generation of younger poets. Alongside her creative work, Qandil has played a significant role in shaping Arabic literary criticism over the last two decades.

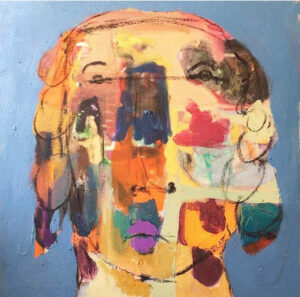

However, it was her 2021 autofiction, Empty Cages, that garnered significant attention in literary circles. Celebrated for its exceptional craftsmanship and its brutally honest exploration of taboo subjects, this work, much like other pieces of autofiction, creates an illusion where readers assume they are peeping into the writer’s private life, attempting to decipher the identities behind the characters, while at its core what the book is attempting to do is to slowly reconstruct an image of the “self” from a shattered mirror, by assembling the sharp pieces, while grappling with the pain and the bleeding.

One of the most unsettling, yet brutally honest, aspects of Empty Cages is how Fatma Qandil recounts her early sexual encounters, not only without shame, but with a startling sense of pleasure and power. She describes how, as a child, she felt “chosen,” the center of desire, the one around whom attention revolved. Rather than caging herself in as a victim, she writes with an unhesitant understanding of the intricate emotions of confusion, pleasure, and pride.

In her book The Bond of Love, Jessica Benjamin argued that girls often conflate being desired with being seen and being seen with being powerful. In a society where girls are taught that their worth lies in being the object of attention, the abusive gaze can initially feel like a form of recognition. Empty Cages could be viewed from this lens, depicting a lonely girl within a household of men, constantly invaded by her brother’s friends, who she enjoys playing with and kissing in the kitchen. However, while traditional feminists like Benjamin might view this desire as a “conflict,” Qandil’s writing insists that life’s desires are more complex than the simplistic linear hierarchy typical of Western feminism. Qandil does not excuse what happened to her, but she refuses to lie about how it felt. Her strength in the book comes not in presenting abuse as a moral lesson, but from conveying the emotional complexities associated with tenderness and moral seriousness.

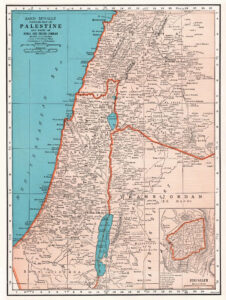

Empty Cages is not just a personal memoir but also reflects the political and social currents that have been shaping Egypt and the surrounding region from the 1960s to the present. The family’s gradual disintegration, shrouded in silence, denial, migration, and poverty, mirrors the fading of Egypt’s postcolonial dream. What began as a promise of liberation and dignity ultimately descended into a reality marred by surveillance, exile, and disappointment.

The portrayal of early childhood in the novel reflects the hope and potential of Egypt’s Nasserite era during the 1960s. The garden scene symbolizes the national mood of that time, capturing a country brimming with hope, and envisioning grand dreams of progress and freedom. But just as the family’s paradisiacal life slowly unravels, so too does Egypt’s national narrative, which begins with the crushing defeat in the 1967 war. Israel bombs Qandil City, forcing the family to flee and seek refuge in West Cairo. The older brother’s psychological breakdown — marked by self-hatred, familial resentment, and alienation — mirrors the broader trauma and disappointment experienced by his entire generation, whose idealism crumbled in the wake of the Israeli bombs that targeted their schools during the war.

The father’s brief decision to work in Saudi Arabia reflects the shift in regional dynamics. Where Egypt was once at the forefront of ideological and cultural movements, the economic and political gravity instead moves eastward toward the Saudi monarchy. Unlike many of his peers who chose to permanently setttle in Saudi Arabia, the father insists on returning after just one year.

Qandil carefully illustrates these parallels without exaggeration; rather than presenting a manifesto, the narrative offers a vivid account of lived experiences through which readers witness the remnants of the Nasserist project, the erosion of the middle class, and the normalization of violence. The narrative is profoundly political, yet understated.

By the 1980s, Egypt’s postcolonial liberation project had entirely fallen apart, paving the way for Sadat’s economic liberalization policies and willingness to accept American influence. The family, paralleling this collapse, sinks into poverty, their connections and support systems dissolving into disorder and isolation. Rather than pursuing higher education or a career, the daughter finds herself trapped in a clandestine and exploitative relationship with a wealthy married man, who visits her occasionally for his own pleasure while also providing financial support for her brother’s medical education and the household’s basic needs. This arrangement starkly reflects Egypt’s wider political subjugation and economic reliance that developed during this period, where aspirations for autonomy were overshadowed by the harsh realities of compromise and the necessity to survive.

Cages are what remains after everyone else has taken what they needed from the woman who built them.

When I first read Empty Cages in Arabic, I cried twice and was close to tears a third time — not out of sadness, but from its language’s sheer beauty and power. Four years later, as I read it in English, masterfully translated by Adam Talib, I did not cry, but I found myself gasping at times when Qandil delivered one of her many incisive lines. Her narrative voice comes directly from her wounds, refusing to be concealed as she encapsulates her journey with her Mother’s last sickness:

“I took Mama back to bed and lay her down on a pillow that I rested on my legs, rocking her to sleep like a baby as she cried.”

In the novel, the narrator hints that her writing will be published as fiction, to protect herself from possible defamation lawsuits brought by her family and her brother’s daughters.

Qandil chronicles the life of an Egyptian woman as she grows from childhood into adulthood, using a clear and chronological narrative that sheds light on the vulnerability, greed, and cruelty that permeate human relationships, particularly among family members, who consciously or unconsciously are driven by their own narcissistic desires. Throughout, the mother stands out as a rare figure, sometimes rising above the fray while maintaining a delicate connection between the narrator and the rest of the family.

Most men in the novel appear opportunistic or defeated, having wasted their dreams and becoming disappointments to those around them. The narrator’s father is a retired, alcoholic teacher whose youthful dreams were dashed when he had to give up his studies to become an engineer, because of his father’s failed business. Ragy, the eldest brother living illegally in Germany, struggles with academic and professional inadequacy, and severe depression, while harboring an unjustified sense of superiority over his family and culture. Ramzy, the middle brother, is a successful physician yet remains emotionally detached, incapable of empathy, love, or moral responsibility, even toward his closest relatives.

The mother and the daughter went through periods where love and desire kept reshaping the relationship, from when the daughter was six years old telling her mother how much she enjoyed being touched, then the father passed away early, followed by the oldest son leaving to Germany, while the young son isolates himself from the two women and use them, for his personal success.

Later in the book, Qandil revisits her father not as a distant symbol of authority but as a fallen man — drunk, sick, exposed. In one scene, she sees him drunk in the street, calling her name. Instead of responding, she silently walks past him, pretending not to know him.

The power shifts: the once-dominant patriarch is now humiliated in public, and the daughter chooses detachment. In another devastating moment, when he is ill and unable to urinate alone, she must help him. He resists, overcome with shame at being seen naked by his daughter, until the mother finally says, “It’s okay. She’s your daughter.” And as daughters are shaped by moments when recognition and subjugation collapse into one another. Here, the daughter no longer seeks recognition from the father. She becomes his caretaker, his witness, even his judge.

Ultimately, Qandil’s Empty Cages illustrates that the female subject isn’t just formed through being desired; she is also shaped by moments of refusal, reversal, and the weight of inherited shame. The body becomes a battleground, where dignity and collapse struggle for dominance.

The “empty cages” in Qandil’s novel are spaces built from care, sacrifice, and emotional labor. But they are empty. And still, women live inside them. In this way, the author expands the feminist critique beyond trauma and into the architecture of empathy. The cages are beautiful and sad. They are what remains after everyone else has taken what they needed from the woman who built them.