How do you fight for freedom in a world where surveillance rules and 73 percent of the world lives under authoritarianism?

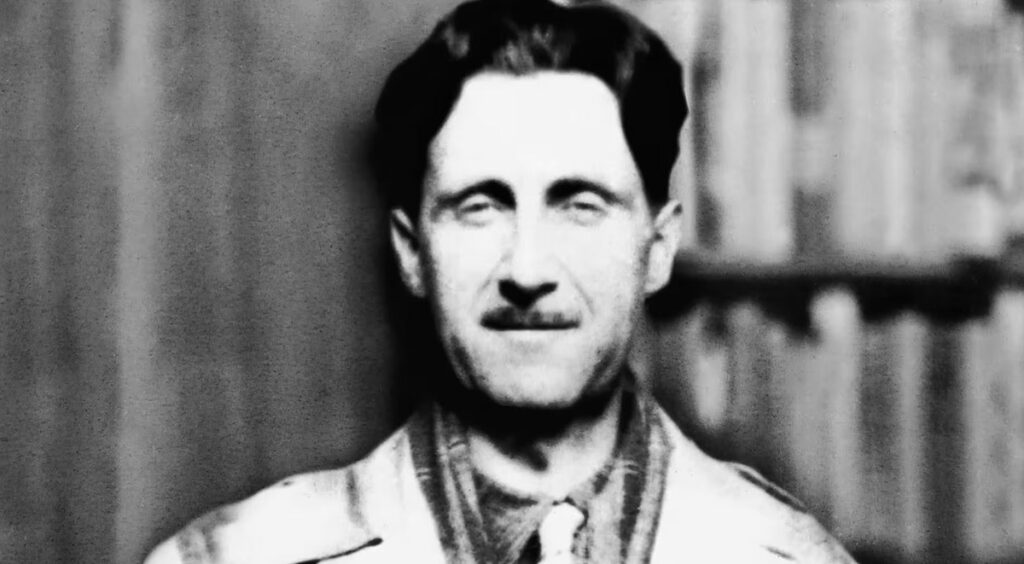

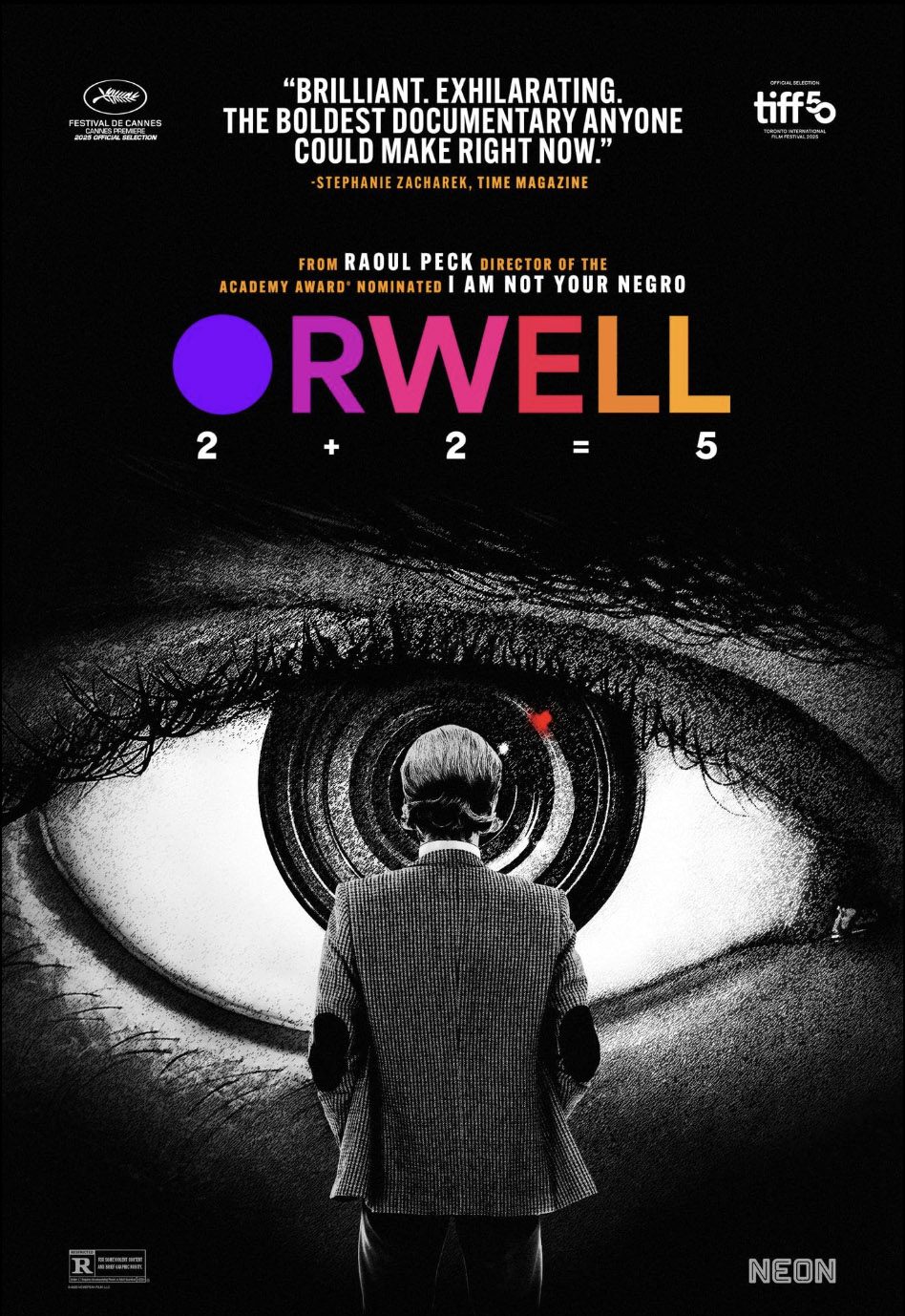

Raoul Peck is a cinematic provocateur. From the Oscar-nominated I Am Not Your Negro to his blistering HBO series Exterminate All the Brutes, his work has fused archival excavation, narration, and uncompromising political critique into a body of cinema that eschews comfort. His latest, Orwell: 2+2=5, continues that project — part essay film, part historical exploration, it is an urgent warning about the authoritarian storm enveloping our planet.

At its core, the film argues that the new totalitarianism isn’t built on secret police or gulags but on the tools we carry in our pockets. Social media — once sold as a democratizing force that would amplify the powerless — has instead become the greatest propaganda machine in history. Algorithms reward outrage, lies travel faster than truth, and despots have learned to flood the digital zone with disinformation until the very notion of reality fractures. “We’ve been split, numbed, and scrolled into submission,” the film argues, such that the promise of the digital age has curdled into its greatest threat.

Peck wastes no time proving it — he opens with a montage that pairs Orwell’s words with images of bombed-out Gaza, populist rallies, and AI-generated distortions, collapsing past and present into a single, destabilizing vision of truth under siege. The film blends archival footage, narration, voiceover, and contemporary commentary to interrogate what it means to live in an Orwellian world now. It is often incendiary and always riveting. Peck’s strength lies in his ability to frame not just a single thesis but a constellation of ideas that intersect across time: Orwell’s insights, the current collapse of democratic norms, the mutation of truth itself. If his scope sometimes feels overwhelming, it is because the problem itself is overwhelming.

Actor Damien Lewis narrates as Orwell, and Peck draws on images and audio from multiple screen adaptations of 1984, moving fluidly between the BBC’s 1954 television production starring Peter Cushing, Michael Anderson’s stark black-and-white 1956 version, and Michael Radford’s 1984 film with John Hurt and Richard Burton. Their aesthetics diverge wildly — grainy monochrome versus lush color, low-budget austerity versus polished production — but the story is always the same: a regime that insists 2+2=5, and a populace forced to comply. These juxtapositions remind us that Orwell’s warning transcends style or decade. However it is filmed, the lie is the constant.

Bombed-out streets and news footage of Palestinian suffering recur as counterpoints to Orwell’s language, exposing how bureaucratic euphemisms like “security operations” and “territorial defense” sanitize violence and moral complicity

The 2+2=5 becomes the film’s refrain, shorthand for the way falsehoods, repeated often enough, become indistinguishable from truth. Peck doesn’t just leave it as metaphor. He grounds it in our present reality: immigrants branded as the cause of crime waves, despite evidence to the contrary; climate change dismissed as a hoax even as wildfires rage and seas rise; “Epstein’s files don’t exist” or “elections are stolen” mutating into gospel for millions, punctuated in the film by footage from the January 6 storming of the Capitol. In Peck’s framing, each of these fallacies is another iteration of 2+2=5, and each acceptance of them a surrender to authoritarianism

Throughout the film, Peck returns to Gaza and the broader Middle East, using the region not as an isolated tragedy but as a case study in how modern empires manage perception. Bombed-out streets and news footage of Palestinian suffering recur as counterpoints to Orwell’s language, exposing how bureaucratic euphemisms like “security operations” and “territorial defense” sanitize violence and moral complicity. In situating Israel’s war in Gaza within a global information war, Peck links modern doublespeak to Orwell’s own colonial awakening under empire.

The revelations Peck cites are staggering. At one point, he emphasizes that 73 percent of the world now lives under authoritarianism. That number is not just a statistic, but also a chilling reminder of how swiftly democratic backsliding has metastasized into global crisis. Authoritarianism is no longer confined to distant regimes or historical cautionary tales; it is the lived reality for the majority of people on Earth.

Peck is unsparing in his assertion. He describes the present as a fascist firestorm, threatening to scorch more territory, fueled by grievances, stoked by conspiracy, legitimized by media ecosystems that no longer distinguish fact from fiction. The flames lick not only at fragile democracies in the Global South but at the very core of the West: the United States, the UK, and Europe. Here, protests are criminalized, journalists are surveilled,* and populist leaders demand loyalty over law. In Peck’s hands, the “Orwellian” is not a metaphor — it is reportage.

Across the film, Peck translates the sanitized language of empire (terms like “peacekeeping operations” and “collateral damage”) into their raw meanings, layering Orwell’s words over scenes of modern conflict, digital propaganda, and manufactured imagery. Even Orwell’s labored breathing becomes part of the sonic landscape, a reminder that truth itself is gasping for air.

And yet, the film is not purely polemic. Peck threads in professional insights, the voices of academics and cultural critics, who tease apart what Orwell anticipated and what has surpassed even the prescient author’s grim imagination. They discuss the psychological toll of constant disinformation, the erosion of a shared reality, the way that “false flags” calcify into facts for those who need them to be true. In their testimony, Orwell’s phrase “the Ministry of Truth” feels less allegory than description.

If the film feels sprawling at times, it is because Peck is unafraid of digression. His essayistic approach privileges accumulation over concision, layering fact upon fact until the weight becomes undeniable. Like his earlier works, Orwell: 2+2=5 is not meant to be consumed passively. It implicates. Peck has always been as much a teacher as a filmmaker, and here he forces his audience to reckon with the stakes. The real question is how does a film like this reach those who have been swept up into this deluge of disinformation and how the film becomes not just another sermon in the church of resistance.

Filmmaker Peck once served as Haiti’s Minister of Culture. He knows what it means to navigate the machinery of power from the inside, just as he knows the fragility of nations consumed by external and internal authoritarian forces. His pivot to filmmaking has produced one of the most formidable political oeuvres of the last two decades. I Am Not Your Negro resurrected James Baldwin to confront America’s racial wound; Exterminate All the Brutes reimagined colonial history as a still-open wound. Orwell: 2+2=5 now joins that canon, situating Orwell as the reluctant prophet of the algorithmic era.

The film is not without its flaws. Its reach is so broad that it sometimes threatens coherence. The constant toggling between archival, film excerpts, expert commentary, and voiceover can come across as indulgent at times. Yet even when the thread frays, the urgency holds it together. Peck surely believes that the stakes justify the ambition, demanding the kind of intellectual and moral attention that few documentaries even attempt.

In the end, Orwell: 2+2=5 leaves us not with solutions but with a question. If truth itself is obliterated, if enough of us can be persuaded that 2+2=5, what hope remains for democracy? Peck does not pretend to offer an answer. Instead, he turns the mirror outward. The danger, he reminds us, is not only authoritarian leaders but also our willingness to be complicit, to choose convenience over truth, apathy over action.

Like Orwell, Peck insists on bearing witness. His films are less about providing comfort than about provoking reckoning. Watching Orwell: 2+2=5 is to feel unsettled, implicated, scorched by the firestorm he describes. It is to recognize that Orwell’s dystopia is not a distant future but our reality; or if not now, just on the horizon. Peck’s film will stand alongside his earlier triumphs as part of a formidable, uncompromising filmography. It provokes, unsettles, and demands attention. And in an age when the very foundation of truth is under siege, there may be no more urgent role for cinema.

* Journalists are also assassinated; since 2022 and the targeted killing of Al Jazeera reporter Shireen Abu Akleh in Jenin, Israel has killed more than 120 journalists, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists — more than all the journalists killed by WWII and the Vietnam War combined.