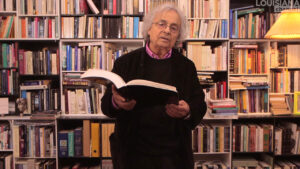

Rabih Alameddine

While reading, I was reminded of a walk I used to take when I was much younger, during the summers in my father’s hometown. Memories of Nasser kept interrupting any attempt at concentration, so I put the book down.

We run from the house before anybody can stop us for chores, through the back, behind the fig trees, which provide us with good cover, and over the back fence to the back road — to the family cemetery, my family’s not his, for he will be buried, is buried now as a matter of fact, in Barouk, his father’s hometown, which was higher up, farther west, than my father’s. I am alive, but he is dead. Who would have bet on that outcome? I feel the stone in my hand as I read, sitting on my sofa, in my house in San Francisco, the sharpness of it, the weight, as I throw it at the gravestone, lapidary phrases seared in my mind like sentences in my book. My cousin Nasser, on one of those walks, stands atop a stone and reads, “Sheikh Nadim Talhouk, 1903-1957,” as he counts how many years that makes. “I can beat that,” he says proudly. He did not. Like a basketball announcer who tells us how well a player shoots his free throws right before the player misses, Nasser jinxed himself. On the walk, that day, he took his penis out and peed on Sheikh Nadim, desecrating what I once thought to be sacred, urine cleansing the old stone, making circles, my eyes fixed, aghast. Seductive blasphemy.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

My mother saved pictures of all her children in photo albums, each organized with dates and descriptions. Almost half of all my pictures in the albums included Nasser. There is a series of four pictures dated March 1961. I was eighteen months old, he was twenty-two months. A professional child photographer must have taken them, for most of the photos looked terribly contrived. We sit close to each other, should to shoulder, and look at a small basket. I put various toys in the basket. He waits for me to finish, after which he takes the basket and stands up. The last picture shows me trying to get up, to follow him most probably, his diapered butt framed in the picture as he leaves.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

I recall a poker game at Ann Arbor. It must have been 1978 or 1979. Nasser was visiting from England where he was attending some pay-for-a-degree college. The game was in my apartment. I was in my room, out for a couple of rounds, trying to reacquaint myself with my lungs after a heavy bout of cigarette-induced coughing. The whole table was Lebanese, as most of my acquaintances were at the time. This was long before I came out. Nasser felt at home. Someone made a joke I did not hear. I heard Nasser’s voice though. “No, no, no. I’ll not have it. Don’t make fun of him while I’m around. I’m his cousin.”

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

Fred, my lover, was jealous of him. It completely confused me. Fred used to say my face would light up whenever I spoke of Nasser. If he called, I would run to the phone. He was like my twin brother. How Fred could be jealous was beyond me. Sometimes I wonder whether I should have blamed Fred for what happened. What difference does it make? He is dead now, too.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

A classical pianist who was once a student in our school came back one day to talk to each class about piano playing. He then tested separately each boy and girl. When it was my turn, he had me turn my back to the piano and played a note, then a second note. I had to tell him whether the second note was lower or higher than the first. I got them all right. I knew I was doing well because he stayed longer with me than with any of the others. With Nasser, the test only lasted about half a minute. The pianist tested me for at least five minutes.

At the end of class, he wanted me to deliver a note to my parents. In it he told my parents that I was talented and I should be given piano lessons. Nobody else in class got a note. I gave the note to my mom when I got home. She waited till after dinner to tell my father. I was sitting in the den, playing with Nasser quietly, which we were supposed to do when my father was home. We heard my mother tell my father that I should be taking piano lessons. We heard my father say that he did not think it was a good idea. He thought I was too effeminate as it was without piano lessons. I felt Nasser move closer to me. He did not say anything. We sat next to each other and played with the Matchbox cars in front of us.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

A phone conversation:

– I have to get married.

– Why?

– What do you mean why? It’s what I want. People get married.

– I know that. I meant why now?

– Because it’s time. I’m tired of being a bachelor.

– Why all of a sudden?

– I don’t know. I don’t have matching plates.

– What are you talking about?

– I have no idea. Issam slept over at my house while he was here, and then when he went back to Beirut, he told my mom I don’t have matching plates. I don’t even know what matching plates have to do with anything. Mother called and said I needed a wife because I don’t have matching plates.

– You’re getting married because your mother wants you to have matching plates?

– Fuck you. I need a wife. What’s wrong with that? I want someone to greet me when I come home. I want sex. I’m tired of looking for it. We don’t all live in America where everybody fucks like rabbits.

– I thought you were fucking that woman I met.

– She’s married. I can only fuck her when her husband is not there. I need something more permanent.

– So you want to get married?

– That’s what I said. Why are you making a big deal out of this? I want to get married. We’re all going to get married. Why not now? It makes sense. I’m not a young buck anymore. Neither are you, you fucker. You should start thinking about getting married. It’ll make your father happy. You should be happy for me. I tell you I want to get married. You should be happy. What kind of friend are you?

– Hey, I’m happy. If you’re happy, I’m happy. I only wanted to know why now. Who’s the unlucky girl?

– Fuck you. The lucky girl. She’ll be damn lucky. I don’t know yet. We’re looking.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

One of my earliest memories is of an occurrence in a bathroom. I do not know where, or in what house. It is evening. Nasser and I are in the bathroom with a maid. She must be Egyptian or Lebanese because the language is Arabic. The tub is full. We are supposed to take our nightly bath, but we are using the toilet. Both of us need to shit. Nasser sits at the commode for a while. I feel really uncomfortable. I tell the maid that I need to go. She tells Nasser to get up and let me have a go. He complains that he is not done, but gets up anyway. He turns around to plead his case and I see a small, greenish-coloured turd in his anus. I tell him he can go back to the commode and finish. I can wait.

I must have been no more than three.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

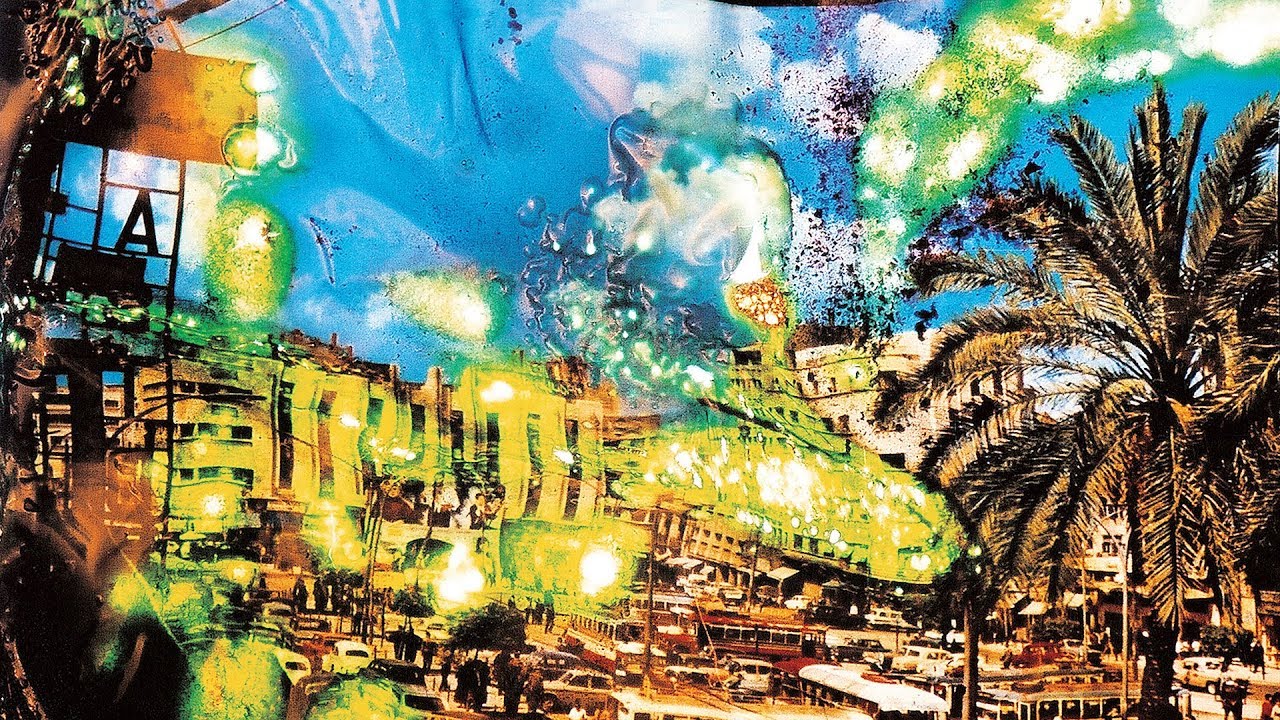

In 1976, before either one of us left for school, during a lull in the fighting, we were in Chouiefat, driving towards Beirut. Nasser was driving his father’s car without his father knowing. Whenever his father had a card game, Nasser stole the car for a couple of hours and we took turns driving. A well-dressed man waved at us to stop.

He asked us nicely if he could ride with us to Beirut since he was in a hurry. He sat in the back behind Nasser. He was charming as we conversed with us. He treated us like adults. As we drove, we noticed a new checkpoint on the road. Nasser started cursing. He hoped nobody would recognise him and tell his father. I thought maybe they would figure we had no license. Our passenger calmly told us not to worry. It was not us they were after. He looked distracted. At the checkpoint, a man in civilian clothes with a big handgun put his head in the window. He smiled at us. He said something about the danger of picking up strangers. The man then bent Nasser’s head with his left hand and with the other shot our passenger until the bullets ran out. Blood spurted everywhere. Our passenger died with a smile on his face, as if looking forward to death. It was the closest I would get to see first-hand the new breed of Lebanese fighters, those who would dedicate themselves to the ultimate sacrifice. I sat with my back to the window, facing the man with the gun, mouth agape. He let go of Nasser’s head.

“You never saw what I look like, right?” he asked us. He sneered. “I don’t want you young boys getting into any kind of trouble. Do we understand each other?”

Nasser could not even look at him. He was staring straight ahead. He could not bring himself to move.

“Do we understand each other?” the man repeated more sternly.

Nasser still could not move. He seemed paralyzed. “We didn’t see anything,” I screamed in a high-pitched voice. “We didn’t see nothing.”

“That’s good. Now why don’t you drive home.”

Nasser still stared ahead, unable to move a muscle. The man wanted us out of there, but Nasser could not move. Finally, I struck the back of Nasser’s head with my hand. “Move,” I screamed as loudly as I could. Finally, he looked at me. “Drive,” I yelled again. He put his foot to the pedal and we were out of there.

We drove for less than a kilometer. When we got to Khalde, I told Nasser to stop at the side of the road. I got him out of the car and walked him over to the beach. I dragged him into the water, both of us fully clothed. I washed him, washed the blood off. He let me dunk his head in the water to untangle the blood. I washed him, punctiliously and ritualistically, like washing the dead, or a blood baptism, the color intensifying in the water surrounding us and then dissipating quickly. I tried to remove as much of the blood as possible.

Once done, I took his hand and he followed. I walked him home, hand in hand, all the way. We left the car. It took us an hour and a half to get to his house. He was still unable to say anything and I did not talk to him, just walked him home. By the time we arrived our clothes were dry. We looked haggard, but that was not unnatural for us. Nobody noticed the remaining bloodstains. I undressed him and threw the clothes out. No reminders were left.

We did not say anything to anybody. The car was found with the corpse of a man who betrayed a militia leader. Everybody knew which handy-man had killed him, but nobody would have been able to touch him in any case. It was assumed the car was stolen to kidnap the man and kill him.

We were free.

We never ever spoke of it.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

Another early recollection. Nasser and I shared a room, as well as a bed, in the mountain house, when we were younger. Through our window, when we first arrived, we always saw a blanket of red. The poppies covered the sloping field. Nasser and I would look through the window trying to find the one, lonesome poppy that was not part of the larger blanket. There was always one, sometimes two, rarely three, independent poppies, not like the rest, different. We loved that poppy.

Years later, I was reminded of that poppy while reading. Proust saw it too. He called it the poppy that had strayed and been lost by its fellows. As I read that, the memories came flooding back.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

I met Fred in grad school. More precisely, I met Fred while I was attending Stanford and he was there to give a speech on the economies of the Middle East. I was in his hotel room within an hour of the end of his speech. I surprised myself. I was still closeted, but allowed myself to be seduced. He came on so strong that not one of my classmates had any doubt as to what was happening. He asked me to leave with him while everyone was still around. He outed me, so to speak.

We were together until he died in 1993, eleven years, only seven of them healthy though.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

I can be walking when all of a sudden something reminds me of him. It can be anything, a flower, a man wearing a pair of jeans in a certain way. If I see a painting, I think of McEnroe, who is now an art dealer, which would of course bring me back to Nasser.

I remember him as he was when he was young, without the moustache, the fat, the alcoholism; fourteen, fifteen maybe.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

“Brother…my hand trembles so I cannot write. I cannot face you either because I will do harm. I am furious. How could you do this to me? I will leave you two…”

The note was crumpled and thrown in the waste basket. He said he did not want me to see it, but he left it in an empty waste basket.

He could not stay in an apartment with my lover and me. Fred was furious. Nasser was furious. They both blamed me.

From the beginning, Fred had wanted me to come out to my family. He thought as long as I did not tell my family about our relationship, I was not really committed to it. I could not. I was out in the United States and closeted in Lebanon. My two lives were separate. I felt it was better for everybody that way. When I met Fred, I cut out anything in my life that was Lebanese. Lebanon became this place I visited twice a year. To this day, I have not told my family.

When Nasser had come to the US for a business meeting, he thought he should come and stay with me for a week in San Francisco. I tried to clean up, to remove any trace of gayness in the house. Fred was livid. He did not allow me to move anything. My clothes and I were to remain in our room. Nothing would be hidden. He thought Nasser, if he loved me as much as I thought he did, would accept the situation. I told Fred there was no way Nasser would accept the situation. Once he knew, all he would be able to see when he looked at me is someone who takes it up the ass. Fred said there was more to being gay than taking it up the ass. Not for Nasser.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

In the beginning it was Ilie Nastasie, the great Romanian. Nasser idolized him. We played tennis constantly. I do not think either one of us could ever have been a great player. We were not athletically gifted, nor were we ever truly coached. Later, Nasser dropped poor Ilie for John. No one was more Nasser’s alter ego than McEnroe. I loved Borg, but Nasser breathed McEnroe. To Nasser, he represented everything that was great about the world.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

I remember I was at Nasser’s house visiting. Fred was sick back in San Francisco, but I needed a break. Nadia was making breakfast. Nasser’s two-year-old daughter, Layla, came in from the kitchen laughing loudly. “Abed is here,” she kept repeating. “Abed is here.”

Nasser picked her up and swung her around. “Don’t embarrass me in front of your uncle,” he chastized her jokingly.

“Who’s Abed?” I asked.

“The driver,” he said. “She has an infatuation for our driver.”

“Layla, you little tramp!” I joked.

He looked at me funny.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

Nasser’s father, Habib, was the family clown. Everybody loved him because he made you laugh, everybody except Nasser. I remember Nasser once telling me, after he had a few drinks, “How can you respect a man who left absolutely nothing but debts for his wife and children?” He truly abhorred his father, which I did not realize while Habib was alive, but which became apparent after his death. My father paid for everything when it came to his sister and her boys. They lacked nothing. Nasser began to idolize my father. It was only gradually that I realized I was being replaced.

After college, Nasser went to work in Kuwait through contacts that my father provided, while I stayed in the United States. First I stayed because of grad school, and then it was a great job with Booz Allen, a management consulting firm. At one point my company wanted to transfer me to Saudi Arabia thinking that as an Arab, I would be able to handle things better than the last couple of executives, who had burned out. I refused. They dangled money, status, and all they could think of, but I did not budge. I was starting a family in San Francisco with Fred. My father could not understand my wanting to stay away. At first, he conceded it was not a bad idea because the war was dragging on, but still he wanted me closer. Europe would have been preferable for him. I did not wish to tell him that the East Coast was too close to Lebanon for my taste. It was not that I disliked my family. I loved them dearly. I wanted a barrier, distance being the best I could think of, between us. I could not see how I could possibly be a complete person, let alone a gay one, if I hung around. Nasser hung around.

Slowly but surely, he became the son my father wished I were. He got married to a nice Druze girl from the mountains. They had a real house with matching plates, and she gave Nasser two boys and a girl. When the war was over, Nasser moved his family back to Beirut. Every time I went back to Beirut, I saw as much of Nasser as I did my family. He spent all of his time with my father.

Nasser picked up my father’s mannerisms. He talked like my father. He walked like my father. He gained weight like my father. He combed his hair like my father. He smoked like my father. And he drank like my father.

He died of heart disease and liver problems, exactly like my father.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

I never liked confrontation. When I was a young boy, Nasser’s mother would always try to get me to fight other children. I never wanted to fight. All the other kids would fight just to please her and other adults. They would constantly wrestle. I could not. My aunt would try to shame me by suggesting that her daughter could beat me. She probably could. She was a tomboy then, and years later, even after a marriage and four kids, I could swear that she was a lesbian. In a different culture, she would have been a true butch dyke, and a happy one at that.

In 1972, Nasser and I started a neighborhood soccer team. We called ourselves The Firebirds, an exotic name. We played a couple of games against other teams. In what would turn out to be our last game with the team, we were playing against another team with an older boy who must have taken offense at the way I looked or something. He wanted me to fight him. He was cussing and harassing me the entire game. At one point, while the game was going on, he started called me names and stood directly in front of me, face-to-face, not allowing me to go around him. I was unsure what to do. All of a sudden, Nasser came out of nowhere and punched him.

I had to enter the fray. While both teams watched, and no one tried to stop anything, Nasser and I beat up on this guy. I never fooled myself into believing that I added much to the fight. Nasser alone could have taken him out. But I tried to help. I held on to one of the older boy’s arms so Nasser could beat him up easier. When the damage was done, the rest of our team made fun of the way I had fought, limp wrist and all. That only made Nasser more furious, screaming at them for standing around and not doing anything. We stopped playing soccer.

Tennis suited us better.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

I dream about Nasser. He is a constant landmark in my dreams. I even have recurring dreams with him in them. In one, Nasser and I, as teenagers again, walk along until we arrive at a fork in the road. We don’t know which road to take. Each road has its own enticing features. We decide that he will go right and I left, and then we can tell each other what it was like when we get home.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

As a young boy, I would walk alone for hours. I would take a book and read as I walked. I would go out of the house to be by myself. I told myself stories of escape. I fantasized about being somewhere else.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

One afternoon, in 1974, Nasser’s mother was playing cards at a friend’s. We skipped school. We had some hash stored up. We ended up in his house, on the sofa, getting wasted. The house reeked, which we thought was totally hilarious.

His father walked in, shocking the hell out of us. “Hi, boys,” he said as he went straight to the bathroom. Nasser looked at me, shrugged, and we started giggling. When Habib came out, he was about to leave again when he looked at his watch.

“Aren’t you boys supposed to be in school?” he asked.

“We’re home to do a science experiment,” Nasser replied.

“That’s good. Okay then, I will see you boys later.” He turned the door handle and was about to leave when his nose twitched. “What’s that smell?”

“Smell?” Nasser asked.

“Must be the oven,” I said.

“The oven?”

“Yes,” I replied. “The science experiment was in the oven.”

“We were trying to dry a bird’s nest,” Nasser added.

“Except we burned it, which is why it smells.”

“It was wet because of the rain.”

“So we put it in the oven to dry,” I went on.

“But there were no eggs, just the nest.”

“And it burned.”

“So it wasn’t a complete failure because we figured out the combustion point.”

Nasser’s father just kept nodding. “That’s good. I’m glad you boys are so studious. Keep up the good work.” And he left.

“Combustion point?” I snickered. We giggled for a couple of hours.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

He told no one about Fred. He tried to pretend he did not know and never saw. Nonetheless, the wall went up. It might have seemed to the naked eye that it was the same, but since that day, it never was.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

I was there when he proposed to his wife, if you could call it that. Once Nasser decided he was going to get married, his mother began the requisite search. Before Nadia, he had gone out with two girls. He flew to Beirut for both dates. They met all the criteria so he asked them out. I had heard rumors, which he denied, that he was proposing on the first or second date and being rejected. He did not deny the rejection, only that he had asked so early on in the game.

With Nadia, I saw it happen. It was their second date. I felt like a Lebanese mezze so I went to a restaurant and they were both there. Nasser could not understand how I would want to be alone in a public place. I had to sit with them. She was pretty. That was the only thing I could be sure of about her. Two hours later, Nasser was talking about the time to get married. He was twenty-eight. She was nineteen. He told her he would be interested in marrying her. She said she had to think about it.

She did look up to the ceiling at one point and whisper to herself, “Nasser and Nadia,” and sort of nodded her head.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

Years later, when I brought up the overheard conversation about piano lessons, Nasser was shocked that I still remembered, surprised that I still blamed my father. He said I finally left home and if it were important that I take piano lessons, I would have. He said if it were such a big deal, I should take piano lessons now. Wasn’t I the free one now?

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

A conversation at the sickbed:

– You know, Nasser was that way too. He was always grumpy when…

– I know. I know. When you both had mumps, you were put in the same room and…

– Okay, okay. I get the hint.

– And you looked like matching bookends, with both your necks so swollen, and they kept you in that room for three weeks…

– I get the picture. I shouldn’t have brought it up.

– And you had a wonderful time, both of you, even though Nasser was grumpy at times, because he’s always grumpy when he’s sick.

– I’m sorry. Okay?

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

In another picture, dated the same in 1961, definitely by the same photographer, Nasser and I are looking up, something above captivating us, probably some toy. We look longingly.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

How old were we then, nine, ten? The cemetery was our favorite place. Few people went through there, so we had the place to ourselves. Our favorite grave was unsigned. It was built like a small pyramid with only three layers of marble. We tried to move the top slab numerous times. It was incredibly heavy. As Nasser got stronger, the marble slab frustrated him more and more.

Years later, after the war, I got Nasser to come walk with me through the cemetery. I wanted to see what it looked like. Exploded shells littered the grounds. The clean-up crews had removed the mines but not the “litter.” Our favourite grave was damaged, large holes and chips in the marble, yet the slab itself was unmoved.

“How could anybody do this?” I asked rhetorically.

“I did that. One time I got really angry, I came here and shot the fucker.”

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

I took him by the hand once — we could not have been more than five or six, maybe seven — and led him to his sister’s room. Everybody was out of the house so it was completely safe, but still he was nervous. I took out all her Barbies.

“You want to play with her dolls?” he asked me.

“Yes, it’s fun.”

“What if we got caught?”

“No one will know.”

“I don’t want to play with dolls.”

“It’s ok. You can be Ken.”

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

There is a word in Lebanese that has no corresponding word in English. Halash, or Yihloush, with a heavy h, means to pull hair out, or to yank someone’s hair. I always assumed that there was a Lebanese word for it, because we do it often, both to other people and ourselves. All you have to do is attend a funeral and you will see what I mean.

I began to wonder why a word did not exist in English when I saw Nasser pull his newly-wed wife’s hair and take her to the bedroom. I was visiting them in Kuwait. They had been married for about seven months. It was about 9:30 at night. Nasser asked if I wanted to get high. I agreed. Nadia had this look of utter disbelief. Nasser went into the bedroom. She followed him. I did not hear what she said, but she seemed perturbed. I heard Nasser say calmly, “What’s the big deal?”

Nasser came out with a pipe. He lit it and gave me a hit. We both smoked. Nadia came out of the bedroom, slamming the door, and went into the bathroom, slamming the door. She obviously had not locked the bathroom door because Nasser follower her and dragged her out by her hair into the bedroom. I heard a slap. Nasser came out as if nothing happened.

“I guess you have not smoked in a while,” I said.

“No, it’s been a while.”

Next day, Nadia was as chipper as ever.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

My father grew suddenly old and sad, fast, with full sail. It happened in only a few months. One trip he was fine; the next, six months later, he seemed engulfed in a sea of sorrows, his face sagging, crushed by the burden of idleness. He had stopped working between those two trips.

One time, my father sat in the den, in his chair, with Layla on his lap. He rocked her as she played with his sparse, white hair. She pulled a strand forward towards his eyes. “Ouch, you little devil, you,” he said, and tickled her. She giggled and tried to do it again. Nasser crouched next to my father. “Be careful when you do that,” he told his daughter. “You don’t want to hurt Grandpa.” He blew his daughter a kiss, and seemingly unconsciously, he flicked my father’s lock of hair back in its place. My father closed his eyes.

I had to return for his funeral two months later.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

When Fred started getting sick, he withdrew. I could not get through to him, did not know how to talk to him. I took care of him, but I was unable to be there for him. When he started getting sick, I began to feel lonely again.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

Nasser and I used to play phone tricks. We were good at it. One of my all time favorites is calling some lady and pretending we were phone technicians. Nasser would tell the woman to put her finger in the number four and dial. Then put it in, say, number seven and dial. Finally he would tell her to put her finger in her ass and dial. My other favorite was calling the pharmacies. I would call one and ask the pharmacist if he had a thermometer. He would say yes, and I would tell him to shove it up his ass, then hang up. Then Nasser would call ten minutes later and in all seriousness ask the pharmacist if some kid had called a while back and told him to shove a thermometer up his ass. The pharmacist would say yes in a huff. Nasser would tell him it was time to take it out, then hang up.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

When Nasser got married, he began to get rounder till he finally achieved his final pachydermatous heft. The last time I saw him, I realised that somewhere in there was the boy I used to know. My father succeeded in killing himself with excess, but it took him a lot longer than Nasser. My beautiful Nasser was a quicker study. He died at thirty-eight, a couple years after my father, a couple years after Fred.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

While reading, I was reminded of a walk I took when I was much younger. Nasser and I were in the cemetery. He was being his usual mischievous self. He challenged me to throw stones at different graves. He looked at a grave of a Talhouk. “I don’t like any of them,” he said. He took his dick out and peed on the grave, on the entire family. “Don’t keep your mouth so open,” he said, “or I will pee in it.” He laughed.

We sat on our favorite grave, the pyramid. He took out his hunting knife. “I have to cut you,” he said. I resisted. I did not understand why we would need actual blood. Wouldn’t calling ourselves blood brothers be enough? He cut the tips of my two fingers and put them in his mouth. He looked me in my eyes the whole time. Shivers ran up my spine. I made small cuts on the tips of his fingers. I put them in my mouth and sucked. He let me suck on his fingers for as long as I wanted.

“We are now brothers,” he said.

First published in TANK ©2000 by Rabih Alameddine. Reprinted by permission of Rabih Alameddine and Aragi Inc. All rights reserved. Special thanks to Malu Halasa.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)