With their focus on publishing in dialects and diversity in the Middle East, contemporary Arabic children’s publishing houses have furthered the debate on how to provide modern literature for children that is different in terms of subject matter and production to books previously published in the region since the 1960s.

Nada Sabet

“Growing up, I hated studying Arabic,” Riham Shendy, the literary scholar and children’s books author, tells me over Zoom. This is surprising since she comes from a family with strong Arabic intellectual ties. Yet what she says is a common sentiment for many who studied in Egypt.

“The key to what is killing children’s publishing is language and not plot. Even books with worldwide appeal like the Gruffalo have failed in the Arab world because they are translated to standard Arabic.”

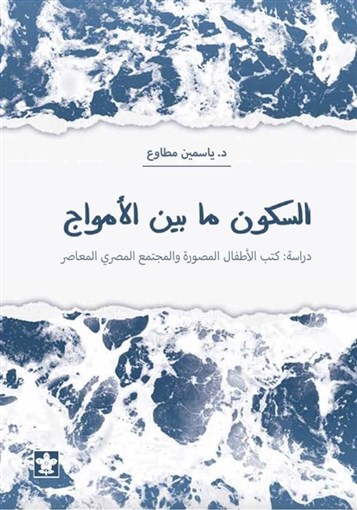

Traditionally children’s books in Arabic are written in classical Arabic, which has been the formal language which all Arabic nations use for writing. It was once associated with Arab nationalism, and in part prepared a younger generation for reading the Qur’an. The language used by newspapers and the majority of books nowadays is standardized Modern Arabic which the purists consider a watered down version of classical Arabic. The argument over language, as Yasmine Motawy points out in her study Silence Between the Waves: Egyptian Children’s Picturebooks and Contemporary Egyptian Society, has been going on for millennia.

Riham wanted to teach her kids Arabic but could not find books exciting enough to engage them and hold their attention, so she ended up writing her own in Egyptian dialect prose and self-publishing some of them. She is currently working on creating a curriculum for young children using the Egyptian dialect that would allow children to learn the language quickly and then transition to standard Arabic.

“I think people don’t appreciate that a big part of why we hated learning Arabic, is that we were given words and sentences we could not understand. To have your first introduction to literacy be words you don’t know is very depressing, and discouraging. There is a whole discipline of early childhood education and childhood linguistics that explains this. So I feel a book like my own kalimat min hayaty (words from my life), directly addresses this gap.”

“I am jealous of children in the west being excited about receiving a book and books being discussed with enthusiasm by children; I had never seen that. Where I came from, children are blamed for not liking books when what is being provided is the problem.”

Riham Shendy is describing a common struggle among Arab parents — finding vibrant Arabic books that resonate with their children. This predicament becomes a gateway to delve into the dynamic shifts and challenges unfolding in the realm of contemporary Arabic children’s publishing, with language at the forefront.

“When an adult reads to a child a text, their energy goes into animating the book so the story comes alive. Standard Arabic books force the adult reader to read, then translate into dialect, which is exhausting. This takes away from the performance and the skill of storytelling especially if the reader needs to stop and explain words or exert effort into countering the frustration that the lack of comprehension is causing the child.”

This is true from the adult’s perspective. From the child’s, learning to decode as books are read becomes impossible as parents translate and thus there is no link between the words on the page and those spoken. Arabic literacy for monolingual kids is their window to education and knowledge. It is a necessity and not a luxury, emphasizes Riham.

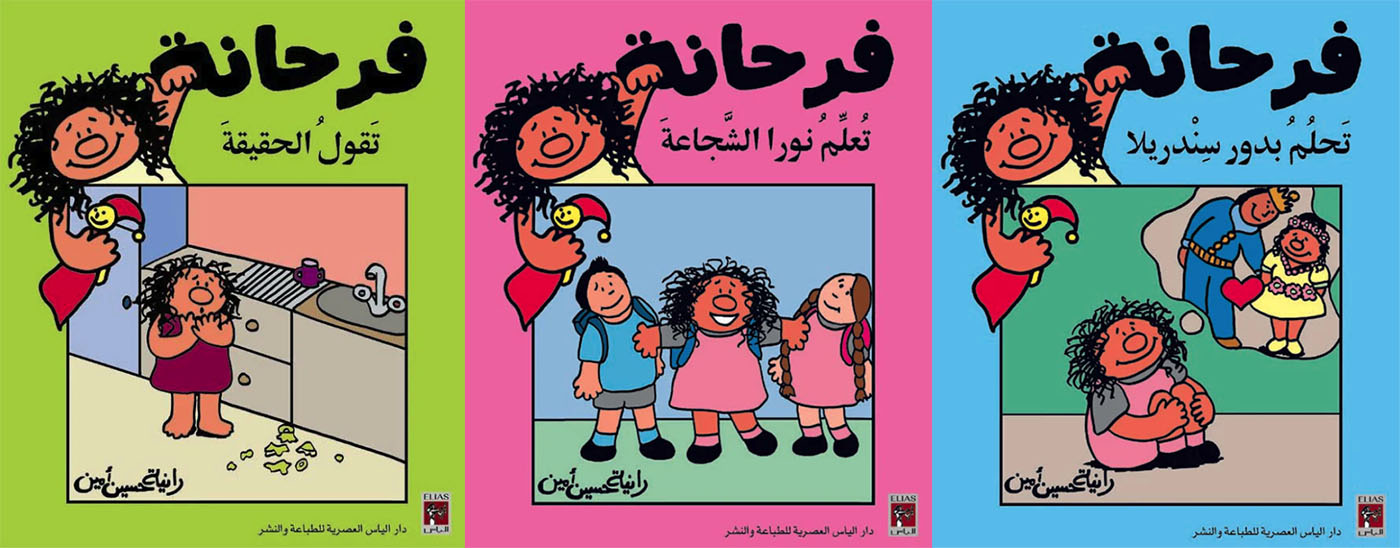

Award winning children and YA author and illustrator Rania Hussain Amin explains, “There are many advantages to publishing in dialect for young children and YA and I would love to write more books in Egyptian dialect, because it is closer to the child and I am very happy that there are more and more books in dialect becoming available. I understand that it limits access to awards, and schools will not support them, but I feel it is the right of children to have books in a language they understand without the frustration of not comprehending the language.”

Language and the importance of a holistic system have come up in every conversation I’ve had with children book authors like Riham and other publishers of children’s books. Voices get loud and full of passion when discussing the topic of language, yet no actual dialogue is happening says Yasmine Motawy, a scholar, critic, translator, editor, consultant, and writing mentor in the field of children’s literature.

The inclusion of colloquial Arabic in storytelling echoes the importance of linguistic resonance in capturing the attention and engagement of young readers.

Manar Hazzaa is an award-winning Egyptian author of children’s books and a research fellow at the Language for Learning Lab at Harvard University. “In storytelling sessions, when I read the same story in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), the children are detached, and miss the jokes, while when I read ‘like we speak’ as my daughter used to say, they are engaged and laughing.”

When Manar initially approached publishers, they refused to publish her first book in dialect and insisted she write them in MSA. Manar now conceives the books in dialect then translates them to standard Arabic, finding words that overlap, thus bridging the gap between standard Arabic and spoken Egyptian.

“This is a laborious process, challenging and entertaining. I want the kids to enjoy the story and the parents reading to remain faithful to the text. Books written in standard Arabic often use words that are similar to the colloquial words used in their particular dialect. The choice of words can indicate where the books have been published. Even with books that use standard Arabic, one can tell from the choice of words; different countries choose words closer to their daily usage and thus the choice of the words is telling of where the book was published.”

Manar goes on to say, “As much as I would love to publish in dialect, and now there are publishers in dialect, I feel I have carved a language format that is mine, attempting to practice linguistic bridging, and feel if I was to abandon it now, no one would take it up.”

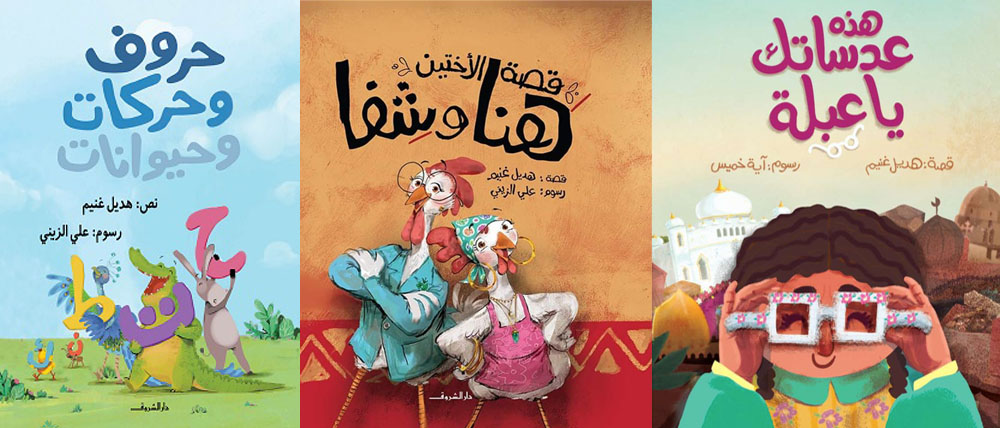

Hadil Ghoneim, an award winning children’s author and researcher, has come up with a similar strategy to bridge the gap between standard Arabic and dialect. In her most recent book, she selects words that work in both standard and dialect but adds diacritical signs to the letters for the parents who wish to emphasize standard Arabic. So the parents have the choice of reading the text in either dialect or standard. This is exemplified by her most recent creation, The Book of Letters and Actions, which caters for younger children. Hadil firmly advocates for a standard approach in writing, rooted in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Her artistry lies in the meticulous selection of words and the interplay between dialect and MSA, exemplifying her commitment to nurturing a cohesive linguistic experience for her readers.

The issues raised by Riham, Manar and Hadil chime with my own experience of not being able to find exciting books in dialect and the need to provide young children with books in a language they can relate to. This is why I co-founded Liblib Publishing which produces vibrant books for young children written in dialect. So far we have 11 titles, suitable for children up to age five in Egyptian dialect, and plan to include other Arabic dialects in the future. We sell mainly online through our website but we have also partnered with certain bookstores such as the Mosaic Rooms and Hone Books, both in the UK, and Egyptian bookstores, like Diwan.

A kind of an ecosystem supporting children’s publishing in dialect is slowly emerging.

Manar stresses that in reality, literacy acquisition includes the intentional work and cooperation of schools, governments and ministries of Education to be onboard. Curriculum design and teacher training has so far ignored diglossia and none of these structures or institutions are currently part of this discussion. Policy changes need to be part of this formula. More people need to publish in dialect to allow for there to be enough material.

Miranda Beshara author, founder and one of the three ladies behind Hadi Badi, an initiative that aims to promote children’s and young adult literature and creative learning in Arabic worldwide. This initiative, started in 2013 as a Facebook group, evolved into a page in 2019 and more recently a website. They attempt to showcase good Arabic books for youth and children through book reviews, recommendations, thematic/age appropriate lists, interviews with industry and opinion pieces and more recently activates and projects around a book.

“Awareness has increased. As more people have entered the industry, there has been diversity in format and language,” explains Miranda. “Awards are on the rise, and this has added incentive and motivation to create better quality books. There is more talk about using children’s books in schools, especially the work of Qatar Foundation and teaching Arabic in the Gulf and the diaspora. A new generation of authors and illustrators are entering the sector, which enriches it.”

Miranda also has a global perspective about the latest trends. In Egypt, books in colloquial language are increasingly popular, while talk about publishing in the mother tongue has been on the rise for the past five years. More self-published books in colloquial and more culturally specific books are available. In Jordan and Lebanon, high quality books on a variety of topics are available, and children’s books make it to the school curriculum. Gulf countries seem to have diversity, as they work with illustrators and authors from all over the world. In Morocco, there is a trend towards bilingual books in Arabic and French. In France, French publisher Actes Sud’s Arabic literature imprint Sindbad Jeunesse and others have released bilingual books in Arabic and French. Translation from Arabic is gaining some traction with Dar Al Salwa from Jordan as well as others. There seems to be a higher rate of young adult books being translated, than picture books from Arabic.

Publishers are being creative in trying to get their books to young readers. Mirame Khamis is the founder of Asfoura Books, a colloquial children’s book publisher aimed at young children. “We are trying to sell in outlets a little differently, as we work on changing the perspective by introducing the idea that books can also be gifted and thus sell at toy stores as well as bookstores. Creating events around the books and focusing on giving an on-the-ground experience for the kids and making the publishing house more approachable and child-friendly to build loyalty and familiarity — this is what I think we are doing differently. So the child reaches out for the book as their chosen form of entertainment.”

Dialect Arab publishers face several barriers when it comes to selling to schools and ministries. They are often not eligible for national book awards. But Mirame has countered this by approaching schools with book readings ideas and selling at school fairs directly to parents. She says so far schools have been receptive.

There are still several challenges facing publishers like Liblib and Asfoura. Marketing is indeed an issue, but raising awareness and working to create a culture of positivity to reading in the Arabic speaking countries goes beyond marketing.

Many in the sector are mothers and their initial impulse came up to directly support their children, and as noble as this is, it is important for publishing houses, distributors, schools and education ministries to explore why we publish for children and what we are trying to achieve. Yasmine Motawy warns publishers of the importance of knowing the child who all these books are being made for as well as the underlining discourse, ideologies and intent behind the making of children’s books.

Mirame admits, “I would like there to be a faster route to market for smaller publishers, with open distribution channels and the right media and attention to push. There is a great deal of talent and creativity in the Arab world but creatives are not focused on children. We need to stop adopting western content and create our own. I would love for us to outpace the need as opposed to constantly trying to catch up.”

The exploration of contemporary Arabic children’s publishing intricately weaves together narratives of linguistic diversity, experimentation, and educational implications. From the grassroots efforts of individual authors to the broader initiatives reshaping the industry, the common thread is language — a tool that shapes narratives, builds bridges, and opens windows to education and knowledge in the Arabic-speaking world. The journey forward involves not only confronting linguistic challenges but also celebrating the richness and diversity of language as an integral part of the magical world of children’s literature.