TMR Interview

Hisham Bustani

interviewed by Rana Asfour

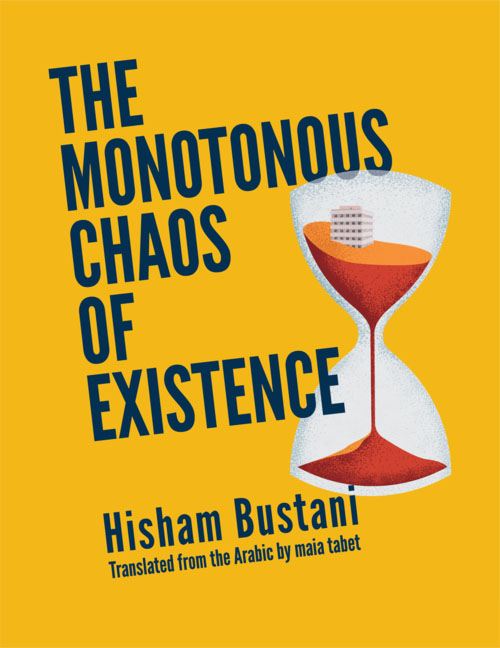

Hisham Bustani is an award-winning Jordanian author of five collections of short fiction and poetry. He was born in Amman and much of his work revolves around issues related to social and political change, particularly the dystopian experience of post-colonial modernity in the Arab world. Critics have described his writing as bringing a new wave of surrealism to Arabic literary culture, which missed the surrealist revolution of the last century: “He belongs to an angry new Arab generation. Indeed, he is at the forefront of this generation, combining an unbounded modernist literary sensibility with a vision for total change.” His work has been translated into many languages, with English language translations appearing in such journals as the Kenyan Review, the Georgia Review, Black Warrior Review, The Poetry Review, Modern Poetry in Translation, Work Literature Today and the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly. His fiction has been collected in anthologies such as The Best Asian Short Stories, The Ordinary Chaos of Being Human, Tales from Many Muslim Worlds, The Radiant of the Short Story, Fiction from Around the Globe and Influence in Confluence: East and West, a Global Anthology on the Short Story. Hisham Bustani is also the Arabic fiction editor at The Common. His latest story collection is The Monotonous Chaos of Existence, translated by maia tablet [sic], published by Mason Jar Press.

Rana Asfour On page 130 of The Monotonous Chaos of Existence, you say there is nobody outside of history. And then in one of your interviews you described writing as a historical process. So, is writing a historical process for you and should all writing be a historical process?

Hisham Bustani

There is no writing that is outside history, and by history I mean the continuous unravelling of events, and our entanglement with them, in the real world; history as an unavoidable “train of consequences”, if I was to quote the Megadeth song. There’s this myth about writers, especially poets, portraying themselves as prophetic, musing on life as if from somewhere outside the world. But we are part of what in physics and cosmology is the observable universe; to us, there’s nothing outside the observable universe, we cannot interact with whatever is outside it. The writer, as everyone and everything else, exists, interacts, functions, and forms emotions and impressions within the observable universe. Our senses, what we see, what we feel, what we think, are all part of the processes of this universe, and, therefore, part of its/our cumulative, interconnected history. I try to always focus on these points to explain why I think writing, as all arts, are practiced within the confines of the world and its history, never outside it. For me, the position of “art for art” is an impossible one, because even writers who want to distance themselves from what they would call the political, the everyday, the mundane, are taking an ideological position in response to the world or parts of it, and it’s a position within history itself, within what they reject to interact with. Many times, by declining to participate in history and adopting an “I don’t care” or “I am only interested in art” stance, blinding the interactive critical eye, one might be agreeing to, supporting, and sustaining injustice. If we’re talking about authoritarian regimes, oppressive societies, colonization, occupation, or the climate today, looking the other way means adding to the injustice, and the problems that are created historically, in that process. Shying from criticism and action within history, one becomes a culprit in, and a facilitator of, injustice. That is a political-historical choice as well.

The Markaz Review

In this book at times it’s almost as if history has collapsed. You’re writing fiction but it’s also a creative documentary, it’s creative nonfiction. It’s poetic. There are many ways to define this piece, and one of them is the merging of history with the present.

Hisham Bustani

Part of my writing approach relies on capturing history and memory, transforming them from something distant and detached, to something alive and relevant to me, to the reader, and to the present moment. The original Arabic text of The Monotonous Chaos of Existence, as much of my earlier writing, had many documentary elements, condensed mainly in footnotes and archival supplements to the fictional texts, which aims — in one of its many aspects — at bringing back what people would consider distant memories and events that are definite precursors of “now,” things that are over and done with, are “dead” in the past, remembered, yes, but (seemingly) no longer relevant. I re-call and re-invent that past in the present, shove it in the face of readers so they’re obliged to deal with them, make connections with their own life now, with what’s happening today, jump for a ride on the Train of Consequences. Also, one of my main concerns in writing is to establish a partnership with readers, empowering them to become co-creators of the text, and documentary footnotes and archival material, extending the fictional treatment to past events, add to this potential. My footnotes are non-interventionist, they don’t interrupt your reading, but you stumble upon them. You define your own space in, and understanding of, that piece, and then boom! You have footnotes, archival photographs or other archival material, new input is thus introduced, communicating a different perspective, revealing another layer or depth. As a result, you immediately have another reading established in your mind. You might be tempted to read the text again based on the “revelations” in the footnotes, reaching yet another interpretation of the text. This is but one application of how I can establish a co-authoring relationship with the reader, and mobilization of history, as both a philosophical concept related to the observable universe, or as a point in the past that continues to exist in the present by its dictating precedence, is essential in achieving this partnership.

TMR

Can you talk about how Arab surrealism kind of washed over the entire Middle East and North Africa at a certain time, and isn’t Arab surrealism its own particular kind of surrealism?

Hisham Bustani

Surrealism is how many Arab critics define or “tag” my writing, but to be frank, I don’t describe my writing as surrealist. I am a huge fan of surrealist approaches in art, and I am very much influenced by the surrealists, but I tend to describe my own literary work in fiction, poetry, and hybrids as meta-realist. Yet, at the end of the day, I don’t care how a critic, or a reader, would categorize a piece of artistic writing. The genre of a literary piece is not important if it belongs to “art”; that is, it is executed utilizing artistic approaches and techniques. There are a lot of things going on in my texts that can be described in different ways: My book The Perception of Meaning (Syracuse University Press, 2015), what I’d comfortably describe as poetry, was released as a collection of flash fictions. That means nothing to the text or to the writer. What I’m concerned with: Is this text literary or artistic? That is definition enough for me.

Back to surrealism, I believe the surrealist movement(s) in the Arab region has not been researched well. There was a strong movement in Egypt for example, with Ramses Younan, Georges Henein, Anwar Kamel, Inji Aflatoun and other artists and writers at its lead, and they’ve produced great works. Although there has been a renewed interest in literary and artistic contributions, much of it remains unknown. Non-mainstream and renegade currents and artists in the Arab world are obscured and deliberately sidelined, first by ruling regimes, and second by the absence of serious literary and art critics and historians. Being a surrealist or a non-conformist artist and writer means reserving a semi-permanent seat in the margins, loosing acknowledgement, recognition and exposure, but, one gains their freedom, integrity, credibility, and self-respect; what’s an artist without these?

TMR

In terms of the theme of historicity and time, I noticed a lot of references to place and space and how layers of time overlap within a certain space. I really loved the first story, where a man is being modernized and buildings are being destroyed. What I like about it is that it’s a very local narrative, but it’s also universal, because the same kind of story could be told in many places around the world. I wondered if you had any comment about the theme of place or space and how you’ve used that?

Hisham Bustani

Space and place are an integral part of my writing. This is very much reflected in my piece “Settling: Towards an Arabic translation of the English word ‘Home’” published earlier in The Markaz Review. It deals with the complicated notion of home, a “place” that is not just space, but also time, emotions, and relationships. Home as a spatial-temporal-emotional construct is very distorted in the Arab region, especially in places like my home city Amman, where things change fast, and change tremendously. Amman is hastily and haphazardly being reconfigured to be a cosmopolitan, Dubai-like city, while at the same time losing its distinct character, its distinct style of architecture and urbaneness: limestone houses, built on hills that surround a pulsating heart: a small balad or downtown area, with a running stream, al-Sayl. In this process of pseudo-modernization, the city is losing its “soul” and the urban-civil connections and interactions between its people are being severed and destroyed. This is examined in the story you mentioned, entitled “City Nightmares.” The connection between space and time is also established in memory, and memory for me is the “now,” the present, because when one recalls a memory, it is recalled for a reason in the present, in response to the present. Each memory is a re-fabrication, a re-collection of an old event that responds to a precursor happening now, in real present time. In response to the current transformations of Amman, my own memory as a child resurfaces, as well as the memories of my father (born in Amman in 1937), and those of my paternal aunt (born in Amman in 1919). You see, one’s memory is a complicated construct of other people’s memories as well, merging into an amorphous structure that becomes a reference point for the present, the latter influencing it by its selective recalling and reshaping. The recollection of a past event is, almost always, an impression about, or an interaction with, a present event or transformation.

TMR

On that note, because I’ve been away from Amman for over 20 years, this was a very nostalgic read for me, reading the stories of the past contrasted with what’s happening now — seeing all the social issues and changes [you deal with], in addition to the changes in time and place, especially with the photographs that you use at the beginning, of your father, and where he went to school — which happens to be exactly where my father went to school as well. For me, the reading experience felt very personal, but it was also a very uncomfortable read, as you move along through the stories, because it felt like a mirror reflected back on myself as a Jordanian. We have these issues lurking beneath the surface, but we don’t discuss these issues, so when they pop out at you from the pages of the book, you feel a little bit of discomfort reading, which is actually a very good thing if a writer can produce the discomfort, because it then forces you to think and to talk about these issues. And once they’re out, you can never pretend not to see these problems. I want to ask how you did the layout of the stories, how you came up with the parts, and how you collected them all together?

Hisham Bustani

Thank you for bringing the word “discomfort” into the conversation. Indeed, my intention is to disturb the falsely reassuring notion of comfort by positioning readers directly in front of often ignored matters which they continuously choose to look away from or treat as non-existent. This is done by utilizing form to deliver a series of “slaps” that are the fragmented-interconnected sections of the text. I tend to write in fragments, I write at different times and in different lengths, and everything goes into a folder. There are many things in that folder: paper scraps, tissue paper with some writing, a restaurant receipt bill with a paragraph on the back, sometimes entire notebooks. Once I feel that the driving-force behind a current phase of writing has reached a certain point of fulfillment, then I know the writing has reached the “book phase,” and I then proceed with taking a couple of weeks away from daily life, a period of literary isolation of sorts, reformulating the contents of the folder into a primordial book, which I’ll put away for a couple of months, and return to with a more detailed, editorial eye. Since all the texts of a folder were produced in a somehow homogenous mental-emotional state, they tend to fit together, have an interconnecting thread that runs subtly through them. Some pieces are more closely related than others, and a sub-context, or say, a direction or flow, becomes evident, so the sections are assembled accordingly and are born within the book.

You can see all this in action within The Monotonous Chaos of Existence. An illustrative example of a fragmented-interconnected short story narrative can be found in “Crossing,” where the story structure moves from a piece of biographical fiction, on to a mythologized piece of historical fiction, then concluding with a meta-realist text that utilizes elements of phantasy and surrealism, while incorporating archival photographs and documents, and ample footnotes that are themselves mini-stories. The book (as a whole) moves from an initial, existential, point of “Disturbance” (the first section of the book), into “GAZA,” a massive manifestation and culmination of the former, paving the way to social reflections that include an interrogation of gender roles, love and sexual relationships, in a final section that feels “Like a Dream.” All my books are constructed along these lines. I like looking at my writing as beads on a string, one node is part of a continuum with others, and they can be approached from any direction. The pieces of one of my books (The Perception of Meaning, mentioned earlier) are numbered, but one can read them in reverse and the book will work too, although in a different way. I also look at my writing as a series of collective projects, to be read as books rather than individual, separate, pieces. This is why I rarely publish individual pieces in the Arabic original before the publication of the book that contains them. One strange imaginary scene I often respond with when asked about my writing and what might be its desired effect on readers: I imagine a reader pinned against a wall, and myself standing with buckets filled with all sorts of paints, colors, smells, emotions, questions, splashing them with its contents. This desired effect cannot be accomplished by a single piece; a book is a much more effective tool towards that result, it might be more abled in relating emotions, feelings and impressions, allowing them to interact within each reader more slowly, more deeply, and more comprehensively.

TMR

The reader can appreciate how gender is explored in The Monotonous Chaos of Existence, in the story “Nicotine,” for instance, how you create multiplicity in an individual, how at times we’re all several genders at the same time, and we have these interior conversations.

Hisham Bustani

Gender roles and performances, gender identities, the complex personal-societal multiplicity, and the different dimensions that constitute each person and their relationships with others and the world, are main concerns that I try to explore through literature, usually in a subtle and multilayered way. After all, we have a lot of things affecting us internally, and are expressed in our daily lives, often in contradictory ways. This is how humans function and go about making the compromises that are their lives. In Jordan, like in many other parts of the Arab region, many writers and artists are not courageous enough to critically engage with controversial issues, especially those that touch on identity issues, in their many manifestations. Gender identities and roles are one aspect of this dilemma, which is often portrayed as an internal personal confrontation with oneself: a crusade of the individual against society. Complicating this view (which is true in some respects) is the role of authority, and postcolonial realities, which take us into another manifestation of identity: that related to origins, where you “originally” come from. Jordan is a good illuminating example on this subject. Everybody knows about the officially sponsored rift between Jordanians of East Bank (Jordanian) descent and Jordanians of West Bank (Palestinian) descent.

The “banks” here are of the river Jordan which, before colonialism, was never a barrier or a political border, and was witness to an interconnected socio-economic existence for centuries. The regime mobilizes these postcolonial identities to pit people against each other and maintain its tight grip on authority by a reincarnation of the “Divide and Rule” dictum. It is hard to believe that it wasn’t until 2010, when I published my story “Faisaly and Wehdat,” the title of which derived from the names of the two football teams through which this division takes a formal, material, officially sanctioned existence, that we had the first-ever piece of fiction that deals with this issue. That writers were part of the denial process is crazy, but that’s the case, and it’s illustrative of the sort of limits that govern artistic output, with both authoritarian and self- censorship in play.

In a small scene like Jordan, art and literature are tightly monitored and controlled by both government and non-government actors and institutions. The regime’s Ministry of Culture is the main player-controller, and as artists and writers seek acknowledgment, want to be part of “the scene,” seek grants and awards and invitations to conferences and exposure in regime-controlled media, they shy away from thorny issues. My stories “Nicotine” (discussing gender roles and identities) and “Faisaly and Wehdat” (discussing identities based on geographical postcolonial “origins”) are two examples of the critical gaze with which I inspect the plurality of human existence, in its social-political-authoritarian entanglements, with a particular focus on my own society and region. At the same time, such texts constitute an ongoing exercise, a self-challenge that I pose in front of myself in order to test my relationship with my internal censor and my yield to external pressures. It is a way to reassure myself that I am not surrendering to the prevailing (and extremely seductive) conformist culture that promises acknowledgement, exposure, and awards.

TMR

Your translator, maia tabet [sic], was interested in the fact that while you wait and gather separate stories to publish them as a whole in Arabic, you did the opposite with the stories in English translation, publishing them in literary journals. She wondered if that felt like something difficult, going against your own intimate sense of what the book was?

Hisham Bustani

There’s an instance of (normal) contradictory human behavior! It’s very difficult to publish a book of Arabic literature in English translation, in the English-speaking world. This becomes even more complicated when we are talking about a book of experimental, artistic, cross-genre texts. Taking that into consideration, my decision to publish the English translations of my stories individually in literary journals was intended to open the potential for the book’s publication, and I think that strategy was successful. In this case in point, I made the decision based on practical, rather than literary, reasons. This strategy also proved beneficial for my development as a writer, as I got exposed to discussions with literary journal editors, to their edits, suggestions, and comments. These discussions are non-existent in the Arab region. In Jordan, for example, there’s no discussion whatsoever — it is absent not just with one’s publisher and the (non-existing) editors, but also with the public and the community of writers and artists to which one nominally “belongs.”

I’ve talked about this many times — it saddens me that I don’t find literary belonging, nor intellectual fulfilment, within my own society, within my own language, but find it in translation. To me, this is a real dilemma. Publishing individual stories in English translation evolved into a process of engagement with an intellectual writing community, getting feedback, discussing writing, examining its particularities, and developing my own literary tools along the way. Another angle of this found literary discussion and engagement in English translation was the prolonged interactions I have with maia tabet, Alice Guthrie, Thoraya El-Rayyes, Nariman Youssef, and Addie Leak, my wonderful ace translators, over many, many drafts of my work. They interact with me on two separate yet interconnected levels: as attentive readers of the original text in Arabic, and as creative authors of the translated English text. Sometimes, this interaction brought about edits to my original Arabic text. These discussions with literary peers who don’t know me personally but only know my texts, aiming at refining writing and developing its processes, are very fulfilling and useful, and I found them, sadly, yet with utmost gratitude, only in translation.

TMR

In talking about the absence of interlocutors, maia tabet wondered about Arabic poetry journals and literary reviews — even within those spaces, you feel that there is no possibility of having an interlocutor? And what about the fact that often Arabic texts are not even proofread — the idea of an editor who has an input into a writer’s texts is unheard of in the Arab world, because writers are elevated on such a pedestal that you can’t even suggest that they might change something. The notion of a developmental editor in the Arab world is anathema, is it not?

Hisham Bustani

Most of the serious Arabic literary reviews have closed shop, and the medium of a pan-Arab literary discussion forum (like what al-Adab magazine used to represent, for example) is now absent. Even when those were still present, and I published in so many of them, the one and only active intellectual interlocutor I ever had as an editor was the late Samah Idriss, who, unlike his counterparts in other journals, took his editorial role very seriously, and was intellectually and linguistically well-equipped to do so. Sadly, al-Adab stopped producing print issues and became exclusively electronic, deterring my previous active contribution to it, and Samah left us early. Therefore, I’ve lost not only a dear and close friend, but the only editorial interlocutor I’ve ever had in the Arabic language.

To substitute this major lack, the standard procedure is to revert to friends, both writers and non-writers, and ask them to read my manuscripts, give me their comments, identify my mistakes and shortcomings. The problem of non-existing editors in the Arab region is rooted in a complicated web of unfortunate “traditions”: the first being that the vast majority of Arab publishers are simply printing presses that charge authors for publishing their books and have minimal or no interest in editorial processes or even transforming the book into a refined commodity and marketing it. They’ve made their money upfront, they care less about the quality of the product, and they don’t invest in specialized staff or intellectual editors. Second, the local and Arab literary scenes are mainly composed of groups or “clans,” dominated, in turn, by authoritarian institutions connected to governments one way or the other. The latter exert their influence through financial support, grants, awards, festival and conference invitations, acknowledgement and media exposure, etc. Regimes care less about the quality of a book or the refinement of writing. Abdo Khal’s IPAF-winning novel Throwing Sparks is infamous for its massive typos, grammatical and sentence structure mistakes, and mediocre prose. Ibrahim Nasrallah’s IPAF-winning novel The Second War of the Dog is so unbelievably bad to the extent that I literally beg people to read it, and to judge for themselves how the deteriorating literary caliber is set and promoted by what is claimed to be “the most prestigious and important literary prize in the Arab world.” What was said about Arabic writers being elevated on a pedestal might be true for some in times long gone. Now most writers bow shamefully and disgracefully at the feet of money, awards, media exposure, and acknowledgement, all under the control of regimes and their “independent” establishments that are their effective tools of influence. No healthy or serious literary standard can come out of that situation. Al-Adab under Samah Idriss was censored in almost all Arab countries. That is what happens when you take things seriously.

TMR

Can you talk more about the notion of the reader being a collaborator, in the sense of a co-conspirator? I also wanted to ask you to talk about the sense that we tend to grow up in big family homes, and how that relates to memory, not just on an individual level but collectively.

Hisham Bustani

In the Arab region, we still hold collectiveness as a main value. Many still live in big family homes, a sort of an everlasting social security/social solidarity network that is always “there for you.” I personally still live in one of those big family homes. I have my own independent apartment, but it is part of a “family compound” designed by my father (who is also my neighbor) to house all his four children and their families in large, separate, independent apartments within the same building. Our neighbors on the other side of the street are brothers who live in a similar building. My cousins in Zarqa live in a similar building. This echoes the collectiveness that is characteristic of rural, Bedouin and pre-capitalist town communities. There’s a big emphasis on notions of collaboration, assistance, and solidarity. This means that memory is also collective, I’ve talked about that in response to an earlier question above, and it is one of the subjects of a forthcoming bilingual (Arabic –English translation) book about Amman, taking the form of a collaboration between my texts and Linda Al Khoury’s photography. Part of the romanticized nostalgia we both have about Amman is the loss of intimate closeness and the warmth of interpersonal relationships that are village-like and are deformed by the sort of pseudo-modernization and neo-liberalization undertaken by the authority to transform city and urban relations into fragmented spheres of individualized consumerism and non-solidarity. Personal gadgets (like smartphones and tablets) and the “social” media gimmick (both tools and content) also contribute to the fragmentation of society and the rise of the ultimate selfish, isolated, individual.

We’re getting separated by tools and power relations that advertise itself as an uninterrupted connection. What we’re losing is societal solidarity. Individuals are extremely weak and vulnerable in this power relation, and they become very selfish. Once an individual regains their societal position, they become more humbled, more prone to be sensitive towards others, and towards nature as well. This sort of collaboration and collectiveness is also part of my writing approach. I tend to democratize my writing by refusing to guide readers on linear, predetermined pathways of event and character development, or through oppressive details of time, space, and objects. The open, fluid, multilayered way I utilize urges (and requires) the reader to “labor” (as Roland Barthes would put it) and “work” (as Umberto Eco would put it), they must become cocreators, congenators, sometimes taking a piece into totally new terrain. Translation is an excellent application of such an approach, audiovisual collaborations between text, image and sound (like the ones I usually do with Kazz Torabyeh) are another application, and my most recent collaboration with the Egyptian comics artist Mahmoud Hafez to produce a comic book of some of the pieces from The Monotonous Chaos of Existence (entitled: Fawda) is another fascinating application. Being a special kind of active readers, they all took my texts into new terrain, finding in them a multiplicity of different dimensions.

TMR

Can you tell us how you came up with the title, The Monotonous Chaos of Existence?

Hisham Bustani

Choosing book titles are a nightmare for me. They are the last thing I do after writing (or compiling) a book. Titles should be expressive of all the different dynamics at work with a book; the overarching thread that runs through all its texts. It is both the connection and conclusion. With time, book after book, I find myself more inclined to longer and longer titles, as if a book cannot be summoned in two words, but in a poetry-like stanza, a long phrase that summons the energy of the text as a whole; as a “corpus.” A major influence in and driving force behind The Monotonous Chaos of Existence (in form, but also in perspectives) are perspectives drawn from chaos theory and quantum physics. I was trying to utilize, relate, and express chaos theory within a literary treatment of the world, society, people, and politics, and this is how the title came about. I am not sure how it reads in English, I can’t “feel” the English language, and both maia and the publisher (Mason Jar Press) suggested considering other titles at different points in the process of producing the English version. Yet, in the end, it stuck, and I think it successfully captures what the book is all about.

TMR

Hisham, Arabic is such a specific and rich language, and it really has nothing to do with English. You’ve obviously spent some time in the UK and gotten some education in English, you read part of the time in English as well as in Arabic. To what extent do you feel you have to compartmentalize your brain? To put English aside when you’re writing in Arabic? Or on the other hand, does English help you in any creative way?

Hisham Bustani

I do not write creatively in English at all. I don’t feel confident in doing that. When it comes to literary writing, my brain functions in Arabic, and I look at my relationship with the English language and my involvement with it in a way that resembles my involvement with all kinds of (non-literary) arts that I enjoy, and am influenced by, but can’t practice. I read a lot in English, including translations into English, and I’m influenced by what I read. These influences are not just in themes, approaches, and subjects, but also in writing strategies and linguistic technicalities. Yet, I still write in what is a characteristic of the Arabic language: long, complex, interconnected sentences that are heavily loaded with metaphors and are a puzzle of pronouns and tenses to the non-native speaker. I tried to write literature directly in English once, but I hated the piece (entitled “A Summer’s Ruin”). Marguerite Richards, the editor of the anthology in which it was to be published, loved it, and published it, which says a lot about my ability to “feel” English. In an attempt to transcend that problem, I self-translated the piece into Arabic, and I hated it even more!

Language is dynamic, the ultimate condensation of subject and form into one expressive tool. To write literature is to master this dynamic, to know its deeper connotations, to feel its historical and psychological weight and variations, and be confident in the ability to utilize, bend, reshape, and sometimes brake, linguistic forms and the myriad of expressions and emotions they bring forth. I find myself confident doing that in my mother tongue, not in English. On another note, the English language is completely different from Arabic in terms of flow. English words in a sentence all end with a pause, contrary to Arabic words which, through tashkeel, use diacritics to mold and shape and fuse one word in a sentence into the next. The flow in an Arabic sentence seems endless, and as words merge into each other, they create “atmospheres” of sound and emotion that are difficult to reproduce in English. This attribute constitutes a huge advantage in the hands of a writer who wants to artistically employ sound and flow as an integral part of literary writing. Therefore, I find the Arabic language indispensable to my writing practice.