A.J. Naddaff

Between the Parliament and the Royal Pathway in the center of Brussels, not too far from the touristic Grand Place, there is a park with two parallel kiosks serving refreshments: one in which stoners lollygag and smoke joints against a backdrop of Zen music, and another where the more business-casual folk gather after work days to sip cappuccinos. I went to the second kiosk on a clear-skyed July evening, one of the only days this summer in Belgium where there was a week of consecutive sun, to meet the budding Lebanese-Belgo novelist Racha Mounaged.

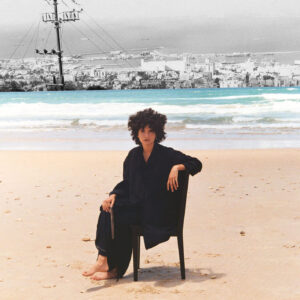

Racha had proposed to meet in the “Park Royal” because it would be more convivial than a traditional café terrace. Yet her attitude and appearance conveyed the formality of precisely that kind of meeting. She dressed in a teal crêpe blouse with finely patterned grey pants and thick heeled black silhouettes. I addressed her in the formal vous and we maintained this civility despite my yearning to bond over our slight age difference and many similarities. We are both Belgian citizens, but outsiders to the country (My mother was born and raised outside Brussels and passed the citizenship onto me through jus sanguinis, whereas Racha recently applied and received citizenship after living and working in Belgium for many years). We also both consider Lebanon home in one way or another (Racha was born and raised between Tripoli and Beirut. I am studying for a master’s in Arabic literature in Beirut, and my father’s grandparents were from Lebanon before they immigrated to Boston). I still hold true to what the famous Lebanese-Egyptian actor Omar Sharif said regarding his sense of belonging: “Once you’re Lebanese, you’re always Lebanese.”

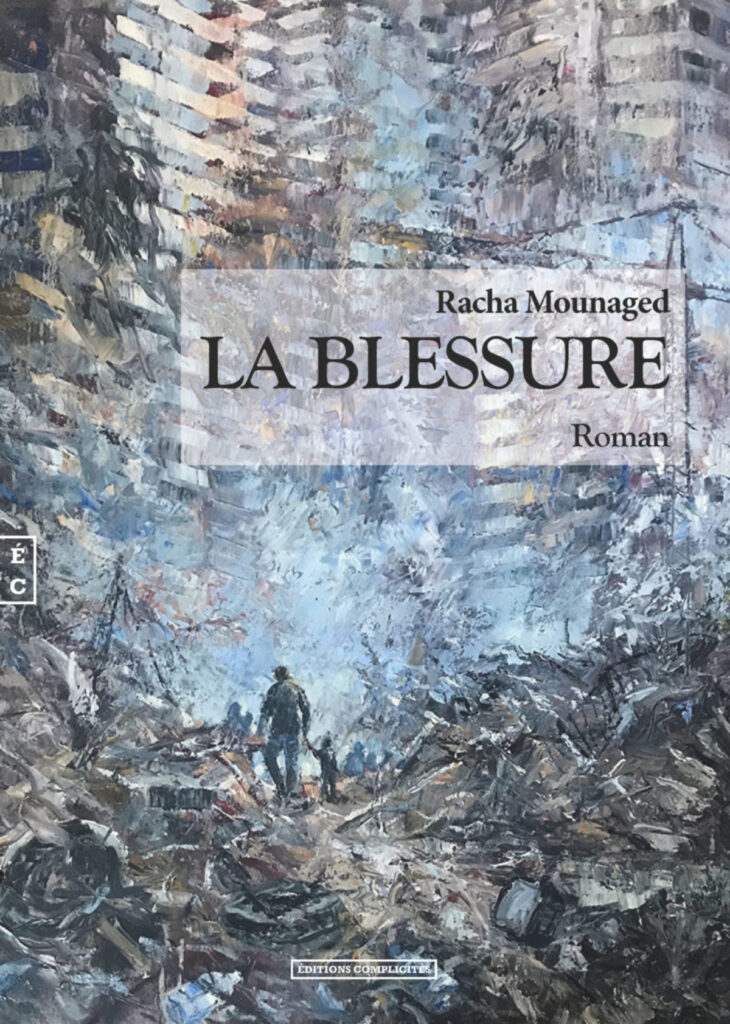

Above all, I devoured her debut 2020 novel La Blessure (perhaps best translated as The Wound) in two days, a book that made the rounds in my family and seemed to speak to everyone because of its heart-wrenching tale and simple, suspenseful, poetic prose. The protagonist, a young child named Jad, resonated with me on a personal level because of his troubled childhood and his final act of hope, although he lived through more adversity than I ever did.

Preparing a long list of questions on the novel’s plot, themes and inspirations was simple. As an aspiring novelist and journalist, questions on the act of writing and current events also came with ease. Yet the formality of the interview and my iPhone recording it on the table stilted the conversation in some ways, or prevented us from getting close as I had wanted on that first encounter.

Today, regarding Lebanon, personally I am lost. I think we have surpassed the stage of Lebanese humor that we were always used to have — the Lebanese who jokes, and says everything is always going well — we are now in a period of depression. A psychologist told me that this depression is more advanced now than previously. ..We are unhappy, things are not okay, we can no longer pretend that things are okay.

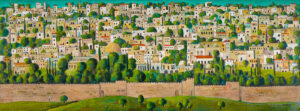

Born in 1982 in Beirut, Racha grew up during the end of the 15-year civil war that engulfed the country and killed more than 100,000 people. She recalled enduring memories of extended family gatherings, picturesque views of countryside and seaside landscape, but also bombings, images of a Beirut scorched. “I lived some episodes and moments where we hid in closets because bombs were exploding around me,” she said.

In addition to war, she lived the trauma of her parent’s brutal separation. While much of her novel, which, as the best fiction often does, employs imaginary events and people as a filter for reality, she displayed a strict faithfulness to this conflict of child loyalty. Or, as she told me, “I wanted to put myself in the shoes of a child and ask: what does it feel like for someone who, in order to keep one of his parents, has to remove the other from his life?”

The innumerable checkpoints across Lebanon divided the country and created a barrier between her father, a sociologist and journalist who lived in Tripoli and wrote in Arabic, and her mother, a Lebanese Francophile who filled her house with French books, and with whom Racha lived in Beirut alongside her sister. These days, the capital is at least a two-hour drive from the northern city of Tripoli, to say nothing of the fuel crisis that further complicates travel.

From a young age, French was inculcated in Racha by her mother, as well as her education at one of the excellent French secular schools in the country, left over from the colonial era: the Lycée of Abdel Kadar in the Mar Elias neighborhood in Beirut. She excelled in all subjects and found refuge in school, but becoming a writer was never a serious consideration. As is typical here and in most other places in the world, science is the key to a successful career, which in wartime Lebanon, just as today, equated with a ticket and stable life abroad.

For the Lebanese, France is usually looked at positively as young people follow fashion and music trends that come out of Paris (unlike Algeria’s ties to France which are typically viewed through an antagonistic lens). “France was a mythical and fantastical place. It was a language that made me dream,” she said with a glitter in her eyes that shone through her pair of thickly framed, rose-gold round glasses. At the age of 18, it was her mastery of French that facilitated the realization of her dream: she received a full scholarship to pursue a degree in biotechnology at the École Nationale Supérieure in Toulouse. Yet, like many other Lebanese who have existed in multiple languages, it created identity problems. Now, although she is more comfortable speaking in Arabic than in French, she writes with more ease in French. “French was the language chosen by my mom and my father was a journalist in Arabic. So I threw out literary Arabic and went towards French, even though I speak with my mom in Arabic” she said, a visible look of befuddlement on her face. “Today, I feel guilty and disloyal to Arabic literature.” She hopes to change that and to approach writing in Arabic in future years.

While estranged from her homeland, she did not join a diasporic network despite inevitable homesickness. She only stayed connected with home through family, friends and social media. In this sense, maybe she would concur with what the Lebanese writer Hoda Barakat described in an essay that was recently translated into English about the diaspora: that there is no community (something I disagree with, as I always have found Lebanese or Arab communities abroad!) Lacking a Lebanese network hit her hardest during the August 4 explosion when she experienced a huge discrepancy between her reality and that of those around her. After August 4, being Lebanese in her normal contexts was unsettling. Questions posed by friends such as “Where are you going to go for vacation?” were utterly absurd.

A decade after emigrating to Belgium, Racha had accomplished everything that looks good on paper: a degree from a top university, a top job in the lucrative pharmaceutical industry, and the security and peace she longed for. But something was missing. She remembered the itching vow that she had long made to her father, before he passed away in 2013, that she would write one day. She kept pushing the promise like a dream deferred until it grew too large to ignore and startled her into action. Suffering already from burnout, she quit her job, put herself in a sort of doleful solitude, and got to writing. “It is the part of me that comes from my father, this is how I’ve interpreted it, I needed to integrate in me this part of him that was more artistic, literary, different from pure scientific research,” she said, as if relieved.

Despite her determination, writing the novel was hard, a fight against both her psychological and material condition and outer voices. People around her started to panic. “My mother had no idea what was happening to me and neither did I. I was going in every direction and I needed to fence it in, finish it and find a job.”

Racha Mounaged’s La Blessure Captures Trauma of Lebanese Civil War

While she took a break from science, the meticulous methodology of project management that had molded her mind helped her tremendously, a type of obsessive planning that might make “some writers pull out their hair.” She wrote a synopsis of chapters on sticky notes and then transferred them into an Excel spreadsheet with a fixed amount of words for each chapter, and set herself to writing 1,200 words per day. Three months later: voilà! An honest encounter with her past birthed the wellspring from which her words poured, and a manuscript was ready.

In her words, she is “atypical and marginal,” and the Covid pandemic satisfied the introverted side of her, allowing her to stay home with her books and ideas. “I did not blame myself because it’s not like anyone was going out,” she said.

With no relationship to the editorial world, she was excited for her debut novel to find a home. Her publisher didn’t have much of a marketing budget, so Racha worked to ensure the novel reached various bookstores in Brussels on her own, and although she wanted it to be put in the shelves of her home country, the economic collapse has made books a luxury.

Her goal, she said, “is to live as a writer, but this is a dream. I learned that the literary career is very difficult and is not a way to make money.”

Above all, she wants to write on subjects that interest her, or rather, heal her. “For me writing is essential, even without recognition. If I am able to live partially from it, that’s great. But if I have to spend money and time to be invisible, I would do that, too.” There is a blueprint to follow to produce best sellers, but she rather have the liberty to write on subjects that interest her.

Racha, who is largely inspired by the symbolism and simplicity of poetry, finds Baudelaire exemplary, a sort of perfection in style, form, and melody. She also has forthcoming poems selected in reviews in Belgium, Switzerland and France.

At this point in the conversation, two hours had passed, and the loud jazz music had shifted to an even louder and quite distracting Édith Piaf. We departed as the sun shone down on us, but I couldn’t help but feel like I had just scratched the surface of Racha’s introspective mind, despite the two and a half hours we spent together. So I called her again, much to my girlfriend’s chagrin, ten minutes after we had departed, and asked if she could come back for a photo since it was the golden hour of the day and the lighting was perfect. She agreed, and said that she appreciated the perfectionist side of me—something we also bonded over.

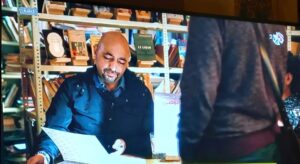

Our second meeting was held at the mini-café inside the nearby Filigrane bookshop, her favorite store where she spends a lot of time reading and browsing the massive selections of categorically arranged books that span several floors. The weather forecast had predicted a day of downpour yet perhaps unsurprisingly, it was wrong and there were only intermittent rains.

I reached out for another meeting with the incentive to introduce Racha to my grandmother’s friend, an 83-year-old dynamic woman by the name of Genevieve, who is a voracious reader of philosophy, was a student of Raymond Aron at the Sorbonne, and had recommended her novel to me in the first place. By coincidence, Racha’s partner Martin, who joined our meeting, was an ideal complement. Like Genevieve, he studied philosophy in Paris, and they were delighted to exchange dialectics. This time, the meeting was far more casual (we spoke in the informal, friendly tu) and far-ranging in topics ranging from Afghanistan to Kant to Islam in Europe and Brussels to imagination.

Just when I looked at my watch, four hours had passed in what was one of the most enjoyable meetings of my life. Perhaps most interesting was our conversations about Racha and Martin’s recent travels to Lebanon and how they navigated the country in the wake of the electricity, water, and gas shortages. (The next day, I would board a plane on my way to Lebanon and the airlines did a fantastic job feigning like we were going to a normal country, or at least, a Lebanon from two years ago before we stepped off the precipice). Yet Racha and Martin had well prepared me for the inferno awaiting me, and I knew that to survive here with all my shortages, I would have to have solidify a mental fortitude and box myself within the Hamra neighborhood near my university. “Just make sure you don’t need gas, get sick, or leave food in your fridge,” Martin warned, advice I’ve since been trying to heed. Recently, I even received my second first doze of the Pfizer vaccine at the American University of Beirut hospital.

As afternoon turned to night, we ambled out the store under the drizzle to catch trains at the metro station, where we finally parted ways. We promised another meeting next time we were all united by fate in the city. I had left with the enormous satisfaction of what I had initially set out to find: a newfound friend bonded by our love for Belgium, Lebanon, French and Lebanese culture, reading, introspection, the Mediterranean and so much more.

Recently, she won a writing scholarship from the federation Wallonia-Brussels to support her second novel, which also explores issues of childhood trauma as well as a young French professional’s challenges integrating into the workforce. “It can be difficult sometimes to be an immigrant here, so to write something in Europe is like landing here,” she said.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)