Maysaa Alajjan recounts her history with two homelands, the one she lived in but was told she didn’t belong to, and the one to which she belonged but never knew.

I was 11 years old when I found out I was Syrian.

Like most profound discoveries, mine happened by coincidence. I was in the ER with my mother and my sister Ghida, who was suffering from a skin allergy flareup. I had watched in fear and fascination as the skin on Ghida’s back, arms, and legs swelled into mountainous red streaks that rose and fell in waves over her tiny body. They itched and swelled until she cried out in pain. Half an hour later, we were in the ER, with my mother frantically searching her purse for Ghida’s legal papers. She produced a small white card and handed it to the cashier clerk. The clerk, a plump middle-aged woman with short blond hair, barely glanced at the card before swiftly returning it to my mother.

“I’m sorry, ma’am,” she said curtly. “Syrian children are not covered by the social security fund.”

I watched as my mother instead produced a wad of cash and paid for Ghida’s medical care. I was surprised my mother didn’t put up a fight of some sort, because she was always fighting for or against something: fighting with my father over his behavior at home, fighting the world over its mistreatment of the poor and the destitute, and fighting for a better life for me and Ghida. Instead, she easily gave in to this stern lady at the counter and did what she asked.

Later that evening, when I had the chance to ask her about what happened in the ER, my mother’s answer was straightforward and simple.

“You and Ghida don’t have Lebanese IDs,” she said gently. “Your Baba is Syrian, therefore you are Syrian, too.”

That, ladies and gentlemen, would be my life encapsulated in a few sentences for the next 24 years. During this period, I would gradually learn what it means to be a Syrian in Lebanon, to be a stranger in your own country, bound by a kinship stronger than words and older than time.

In Lebanon, being born to a Lebanese mother and a non-Lebanese father meant that you carried only the nationality(ies) of your father. Lebanese mothers are forbidden by law to pass on their nationality to their children or spouses. This meant many things. It meant having to renew your residency permit at the Amn el-‘Am (general security) every three years. Otherwise, your presence in Lebanon would be considered illegal, and you would get into trouble with the law. I remember dreading these visits to Amn el-‘Am as a child and begging my mother to exempt me from going, to no avail. It also meant severe travel restrictions to many countries because of Western sanctions applied on Syria, which led the Syrian passport to rank very low in terms of passport power. There were many years when Ghida and I ceased traveling altogether, because we had faced our fair share of visa rejections. However, as we grew older — and our bank accounts grew fatter — things started to look up and we were able to travel to Europe.

A year after that formative conversation with my mother, tragedy struck. Baba, who had previously suffered from heart disease, would die after suffering a stroke in our house in Syria. He was all alone. I remember my mother telling me and Ghida, rather bluntly, that he had died two days earlier. It was a Tuesday. I remember Ghida and I crying as only orphans could cry, weeping with the pain of a loss as raw and enormous as our little hearts could bear.

It went without saying that the loss of Baba would mean the loss of the link that bound us to Syria. With his passing was severed the last tenuous connection Ghida and I had with our country of origin. There would be no more trips to Damascus — Mama would process our legal papers through her lawyer in Syria, and, later on, through the Syrian embassy in Beirut. She would also sell our house there too because “we don’t need it anymore,” she would say. “Your roots are here in Lebanon.”

“Besides,” she would add later when we were older, “the custody battle for you and Ghida was costly enough for me. Syrian law isn’t exactly forgiving.”

In the world of tough kids, being Syrian meant certain punishment. I learned very early on that I could easily get bullied if I revealed, even with a hint of my accent, who I really was. Children are cruel creatures who mercilessly taunt you if you give them a reason to, and Ghida and I were determined not to give our classmates that reason. Our accent was by default Lebanese, and it would stay as such. We were too young to understand the historical forces that were shaping our young lives, but we were sure of one thing: in Lebanon, no one was being celebrated for being Syrian. In fact, the word “Syrian” was, in many ways, synonymous with cheap labor. It was a well-known secret that many Syrians were “illegal migrants” — later called “refugees” — who had crossed the border with Lebanon in search of a better future for their families. The Syrians I knew were mostly poor, uneducated laborers who found ample work in Lebanon’s manual labor market as plumbers, painters, janitors, builders, and the sort.

I remember feeling frustrated and thinking, in my 11-year-old mind, that there had to be more to Syrians — more to us — than just that image of the poor laborer. I decided to ask my mother about it. I went to her study and knocked on the door. She was leaning over some papers on her desk, no doubt editing. She was always editing the work of some writer, even when she was occupied with other things. Being the executive editor of the Institute for Palestine Studies was an all-consuming job, all year long.

“Yes?” she said, without looking up. I remained silent for a few seconds.

“What is it, Maysaa?”

“Mama, I was just wondering. Why does everyone here say that all Syrians are cheap labor?”

“Who says that?”

“Everybody.”

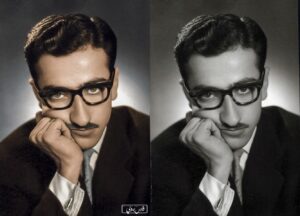

She straightened her posture and looked at me intently. “I want you and your sister to remember this when you think of Syria,” she said, speaking slowly. “I want you to think of all the richness your country has to offer to the world. Do you remember Nizar Qabbani, the poet I told you about?” I nodded. “Well, he was Syrian. So is Adonis and Dureid Laham, and many other artists. Always remember that Syria is a rich country.

And as for the laborers, these people are fleeing oppression and poverty. Therefore, they are deserving of our compassion, because they find very little of it here in Lebanon. Do you understand?” I nodded, not sure whether I should feel mollified. I wasn’t sure I knew all the names she had mentioned, but I was able to grasp her general idea. It rang true with common sense.

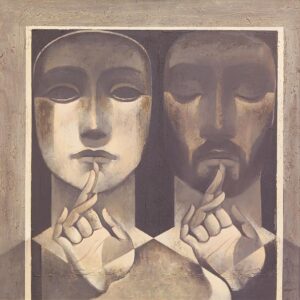

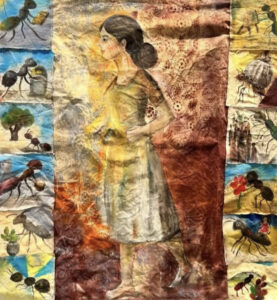

Sara Shamma (Damascus, 1975), Untitled, oil on canvas, 100x100cm, 2024 (courtesy Sara Shamma).

March 2004. I was a gawky 14-year-old with braces and glasses. I was sitting in the front row in geography class. We were studying the history of Lebanon, and Mr. Halawi, our short, stubby teacher, had veered off course again. We’d been learning about Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon and its occupation of the South, a violent assault that would only end with the Lebanese resistance’s heroic liberation of the South on May 25, 2000. But Mr. Halawi, as was his custom, had drifted far from the subject, and my mind had wandered with him.

“Of course, the Israeli occupation is not the only entity to have assaulted Lebanon’s sovereignty,” I remember him saying in his scratchy tone. “Take, for example, the Syrian regime. Syrian troops have been stationed in various Lebanese areas since 1976. They wield great influence over Lebanon’s internal politics and affairs. They practically run the place.”

My heart sank as I thought I heard an agreeable murmur pass through the back row. The class fell very quiet. Mohammad Ali, one of the popular bullies in school, said in a low voice: “My father hates them. He says you can’t pass a checkpoint without running into them.”

As my classmates huddled around him and their murmurs grew louder by the minute, I began to panic. Did Mr. Halawi know my secret? Would he expose me in front of the whole class? I slumped in my seat, praying for the session to be over. When the bell rang, it was all I could do to restrain myself from jumping up and running back home. Once in my room, I lay spread-eagled on my bed and thought hard about what I had just heard. Syria had occupied Lebanon, and that was why the Lebanese didn’t like Syrians. Moreover, Syrian troops were stationed all over Lebanon, and there was nothing the Lebanese could do to get them out.

It was torture to have two countries who hated each other running in my blood. I didn’t know what to make of it. I couldn’t make anything of it. I was too young to carry such a burden. It was all so unfair. I lay in my bed all that afternoon until the slanting sunrays edged further away from my bed and dipped into the curtains.

The year 2005 was, politically speaking, the worst year for Syrians in Lebanon. There were several political assassinations that occurred which helped permanently stain the image of Syrians in the Lebanese collective consciousness.

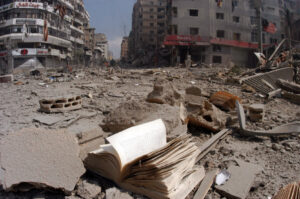

The first was the assassination of Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, which happened on February 14 of that year. I remember that date well because it was Valentine’s Day. After leaving a parliament session in downtown Beirut, Hariri, one of the most popular and decent prime ministers to ever lead Lebanon, was blown to pieces with his entire convoy. Rumor had it that his body was so mutilated that rescuers could only identify him from the ring on his finger. And there was only one known suspect behind his killing at the time: the Syrian Assad regime.

In response to the massacre, huge national protests erupted across the country, calling for the withdrawal of the Syrian army. Sure enough, by May that same year, Syrian troops had withdrawn from Lebanese territory. I thought about what Mr. Halawi had said in geography class. No doubt he was one of the many cheering among the crowds.

Hariri’s murder led to a series of riots and harassment campaigns against Syrians in Lebanon. Shops and houses were burned, and Syrians were evicted from their homes. My family and I were spared any revenge treatment, possibly because of the protection that my mother’s social status offered (children of Lebanese mothers were considered legal residents of Lebanon as long as they renewed their iqamas, or residency permits). To our relief, our nationality remained a secret at school.

More assassinations and bloodshed would follow in the next few years, but it was all somehow contained — at least, that’s what Ghida and I thought, sheltered as we were from the violence outside.

The Syrian civil war began in 2011, just before Ghida and I graduated from college. The civil war served to further stain the image of Syrians, this time cementing them as needy refugees, siphoning resources away from their Lebanese “hosts.” A new concern was added to our list of woes: job hunting. Most employers were merciless when it came to profiling candidates and giving preference to Lebanese ones over foreign applicants. I was luckier than Ghida in a sense, because I had chosen to work in media, a profession that relies on freelancers. But Ghida suffered. She was rejected seven times before securing a position as a procurement officer at a hotel in Beirut.

Despite everything, Ghida and I were considered lucky. We were able to enjoy good social standing and all the privileges that come with it. We had jobs and our fair share of close friends and friendly neighbors. Life was, for the most part, deceptively stable. But there was always the shadow of racism at every Lebanese army checkpoint, every government counter. Always that sneer or a look of surprise from the official involved.

The irony was that while Ghida and I knew exactly what it meant to be Lebanese, we had almost no clue what it meant to be Syrian. We knew Lebanon’s history and geography by heart; we accepted the fact that there was a war waged in this small country every decade or so, and we knew just how far the tentacles of its corruption scheme had reached: into public services, educational institutes, even banks and restaurants. We knew how to work our way around this kind of calculated incompetence. But Syria? What did we know of Syria? I mean no offense to my country of origin when I say I would have gotten lost should it have been required of me to go to Syria to renew my papers, so vast and incomprehensible the country seemed at times.

But there was always the worry in the back of our minds about what we’d do if the Lebanese decided that they’d had enough of the Syrian presence in their country and decided to kick us all out. The turmoil of the years following the Hariri assassination had taught us that we would stand and fight through any legal means necessary. We would not leave Lebanon; we would not leave our home. After all, we are half-Lebanese by blood, and no one can take that away from us.

Looking back at those years, I realize that it was my perception of my nationality, rather than my nationality itself, that caused the most anguish. True, there was a lot of racism against Syrians in Lebanon, but I never once remember standing up for myself against it. When people would comment, in that offhanded manner, that I can virtually “pass for Lebanese” and that I didn’t “look or talk Syrian” — or worse, that I was “lucky I wasn’t Palestinian” — my blood boiled, but I’d smile courteously and accept their “compliment.” I do believe it was a compliment delivered with the best of intentions, but it still hurt, and I smarted under its weight. My situation was indeed better off than that of Palestinians, who were further restricted from certain basic rights such as the right to own property and the right to work in certain professions, but there was no need to gloat over the misery of others. Weren’t we all in the same boat together?

I never repeated what my mother had taught me, that Damascus was the oldest capital in the world, that it had breathtaking heritage preserved in its buildings and old souks, and that you can “hear time whispering as you pass through its alleys.” Instead, I remained quiet, validating their sense of superiority and forfeiting any right to defend my own. It felt like betrayal, but I didn’t have the voice I needed to tell myself otherwise.

For a long time, it felt as though I had chosen Lebanon over Syria. After all, Lebanon was where I had grown up and received my cherished AUB education. It was where I had taken my first steps, worked my first job, and fallen in love. Lebanon was my whole world. But Lebanon doesn’t want you, a sly voice whispered inside my head. It doesn’t want Syrians. How can you embrace a country that doesn’t recognize you?

To say that I have cracked the code of this dilemma would be to lie through my teeth, but there’s something about the passage of time that makes one more mellow and accepting of life and of its injustices. I’ve mellowed over the years and stopped being so angry and confused. I learned to accept life as it is and to bend instead of break. In other words, I learned to accept my nationality and the injustice that comes with it for the simple reason that these things are mine and mine alone. It doesn’t mean I will ever stop fighting for my birth right. On the contrary, I will continue to attend every rally and annual protest organized for the rights of children of Lebanese mothers. However, for one to live in peace, a certain kind of amicable truce with the world is required.

December 2024. After a long, torturous 14-year-old war, Syria is finally free from the grip of the murderous Assad regime. The whole world celebrates. Even I get a few well-meaning pats on the back from people who think I ought to celebrate my good fortune. I watch in amazement as Syrian opposition forces storm Aleppo, then Hama, and then, in the blink of an eye, Damascus. I am fascinated as each of these cities falls like sand castles in the hands of these forces.

In the excitement of the moment, I plan a trip to Damascus. I tell myself that, if the situation remains stable till next spring, I will pay a visit to my old neighborhood. I will walk like Nizar Qabbani in the old alleyways of Damascus and visit the old souks, and maybe fall in love there. I will read the works of poets belonging to the Bilad al-Sham era and dance among their verses.

But the honeymoon doesn’t last. Syria’s transitional period is proving to be violent and bloody. Also, rumors of an impending normalization with Israel start to surface. Suddenly the dream of a free, liberated Syria becomes a chimera. Normalization with Israel would strip Syria of its essential identity as a historically pan Arab country with pan Arab influences. Normalization would not only change the face of Syria as we know it, for the worse (geographically, demographically, and politically), but it would also unleash the imposition of normalization — and thus the fires of hell — on Lebanon.

I never ended up visiting Damascus. In fact, it has been 24 years since I last set foot there, and, judging by circumstance, I might not do so anytime soon. The adrenaline rush I felt during my home city’s “liberation” from the old Syrian regime is gone. Instead, a new, grim resignation to a bleak reality has taken its place. The truth is, I don’t think Syria and I are destined to meet in this lifetime. I have no home in Damascus, no close relatives, no loved ones waiting for my return. It feels as if Syria and I are two parallel lines, close enough but destined not to meet.

I pray that, one day, I will find love in Damascus waiting for me. I will run barefoot in its streets, and bathe in the scent of its jasmines. I will lose myself in the glory of its dusk. And just for a minute, it might even feel like home.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)