Nevine Abraham

Growing up in Shoubra, one of the most populated Christian suburbs of Cairo, I met all my Muslim friends at a French Catholic school, which they and I attended for twelve years. We spent recess together, exchanged visits and play dates, and shared teenage secrets. Our friendship never conjured up our religious identities. My parents rejected the narrative of the “victimized” Copts. Never have I heard them label my friends by their religion nor suggest that I befriend only Christians, unlike many other Coptic families I knew. During Ramadan, I abstained from eating or drinking in public out of consideration for my fasting friends. As other Christians shared Ramadan iftar meals, I did the same; this increased my sense of national belonging.

Friday, our days of worship in churches and mosques, united us (churches also held services on Sunday). Our paths usually crossed shortly after Friday worship, as we lined up together in front of the street vendors’ carts that sell freshly made foul medammes in Qidrah to take home and indulge. The mosque microphones resonated with the calls to prayers while the church bells rang. Spirituality echoed in the streets and at homes. On Christian and Muslim holidays, we exchanged homemade ka’ak, ghorayibba, and petits-fours: if my mother sent our Muslim neighbors a platter of home baked sweets, they were sure to return it filled with their own delicacies. Religions, whether Islam or Christianity, functioned as a basis of our shared cultural practices and traditions.

Ranked 8th out of about 250,000 in Egypt’s General Secondary standardized test of high school known as thanaweya ‘amma and passionate about my specialty in literature and languages, I pursued my dream to be among the one or two who would be selected per academic year to join the graduate studies program, which guarantees a path to a faculty position at my college. Seeing that my two main academic competitors became muhajabat in junior year at Ain Shams University in Cairo, I realized that my chances had diminished. My academic accomplishments and high GPA suddenly became insufficient: I realized I didn’t fit into the perceived societal norms of attending graduate school. For the first time at the age of twenty, I was hit with the truth: I had been naively deluded into believing in a fictitious form of national unity and equality.

Interestingly, my childhood identity challenges stemmed primarily from within the Coptic practices. Specifically, faith, piety, and orthodox rituals have defined the Coptic heritage, which prides itself on its unique ethnicity and purity as natives of pre-Islamic Egypt. The word “Copt” from the Greek “Aigyptos” for Egypt, later adopted by the Arabs as “Qibti,” affirms the Copts’ connection to the land. Despite this seeming homogeneity, attitudes among Copts towards religious practices still vary according to their family culture. The extent to which semi- and strict- followers embraced piety created a subtle hierarchy among Copts and often raised an internal struggle in questioning one’s religious belonging.

In fasting rituals for instance, whereas the majority strictly observes the 200+ days a year of the numerous fasts, including the added Wednesdays and Fridays every week, some —my family included at times, though inconsistently —committed to only part of the long ones: Nativity (45 days) and Lent (55 days). Many, myself excluded, were often eager to show their knowledge of the less-popular saints’ autobiographies, engrave the tattoo of a cross on their wrists, and participate in rigid rituals such as staying up overnight singing praises on the Night of the Apocalypse.

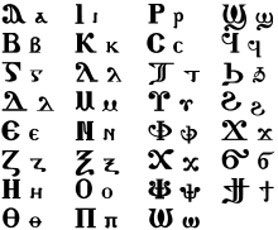

As a child, Sunday school, which my parents encouraged me to attend following Friday church services, accentuated those differences and created internal struggles. There, memorizing the Coptic hymns and Psalms came easy to the majority; for me, it did not. Others enthusiastically recited the tunes and read the Coptic words, while I mumbled and lost interest in that unfamiliar language. I never fathomed its importance as a required staple of my heritage. I did not pursue it perhaps because no one in my family knew it. Sunday school time was too short to allow for teaching the language itself, and I did not find the need to memorize hymns in a language that was no longer spoken except during church services.

“Special” church days were other venues of uneasiness. On Good Friday, I joined those who muttered the few lines I knew, but, out of embarrassment, kept quiet while listening to the singing of those well-versed in the long-sequenced Coptic hymns.

To summon it, I felt a struggle to meet the Coptic Orthodox community’s expectations of its members to preserve its unique heritage, and thus fell short when it came to belonging among the “Coptic Hierarchy” elites.

Faith, piety, and rituals are not the only markers of Coptic identity. The foundation of the Coptic Calendar on the “Era of the Martyrs” or mass execution of thousands of Christians under the rule of the Roman Emperor Diocletian in 284 AD has set the tone for other aspects of the Coptic persona. It fosters the ability to withstand challenges by promoting the rewards of being persecuted, tortured, or even killed through the reliance on God. It embraces an attitude of humility, accepting less than one’s fair share (more on that later), and allows for public invisibility. The Pact or Covenant of Umar (seventh century?), written by the Christians of the newly conquered Muslim territories in Syria, liberated from the Roman Empire and addressed to Muhammad’s second successor or Caliph ͨUmar Ibn Al-Khattab (634-644), functioned as an act of surrender and defined the Christians’ status as Dhimmi people or “people of the book” who ought to be protected. It later included the Christians of Mesopotamia, Jerusalem, and North Africa, along with the Jews.

Through Muslims’ eyes, Christians were viewed as polytheists or worshippers of multiple deities: God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. The self-imposed “obligations” taken upon the Christians, as stated in the Pact, restricted the construction of churches (“We shall not erect in our cities or in their vicinity any new monasteries, churches, hermitages, or monks’ cells”) and homes (“We shall not build our homes higher than theirs”), defined the Dhimmi’s dress code (“We shall not attempt to resemble the Muslims in any way with regard to their dress” “We shall always adorn ourselves in our traditional fashion. We shall bind the zunnār [a type of belt] around our waists”), and asserted their second-class citizenship (“We shall show respect to the Muslims and shall rise from our seats when they wish to sit down”). This was in addition to choosing between the imposed jizya, or tax, or conversion to Islam. The Pact remained in effect under the subsequent caliphates: the Abbasid (747-1252), Mamluk (1252-1517), and Ottoman (1517-1798) periods.

In modern times, Copts, who constitute 10-15% of the Egyptian population, had to abide by the Muslim majority’s societal expectations founded on certain “moral codes.” Though both groups share the same conservative values since religion permeates their daily lives and language, putting the burden of social morality on the shoulders of women, Muslim and Christian alike, has sometimes complicated Muslim-Christian relations in workplaces, for instance. Embracing the hijab has set a hegemonic expectation of the female Copts’ public appearance. My mother’s muhajabat co-workers often reproached her for her uncovered, blond-colored hair and short-sleeved tops, deemed haram by society’s standards, and advised her to cover them. Though changing the length of clothes proved feasible for her, covering her hair, traditionally restricted to church services as instructed in the Bible, meant posing as a Muslim; she could not, prompting a compromise of her acceptance at work.

In the streets, I recall an incident of a bearded man who firmly grabbed my friend’s arm, warning her of God’s punishment if she did not cover her naked flesh, and another who screamed “’a’uthu billah min ghadab illah” (“I seek refuge with God from the wrath of God”) in my ear in disapproval of my wearing a tee-shirt. Despite the realization that such behaviors derogated our religion and denied us the right to be respected in public space while giving the majority’s religion moral impunity, many Copts still somehow believed in their equal citizenship and the “eternal” rewards of these challenges. These incidents, which my family viewed as isolated, gradually furthered my belief that gender and religion consigned me to a marginal place in my homeland.

Surely, clothing and appearance do not constitute an obstacle to the male Copts’ social acceptance. However, their religious identity can be stigmatized differently. Only in the U.S. did I hear their stories, mainly because Copts never dared complain due to the systematic marginalization of their voices in Egypt. Their childhood memories comprised being chased on a weekly basis by Muslim children throwing stones at them, labeled ‘Issa (Muslim for “Jesus”) by their public-school teachers, and denied inclusion in the top academic classes restricted only to the highest achieving Muslim majority. They never processed the impact of such stigmatization, which reduced them to a mere innominate minority and excluded them until they left Egypt. Those who enjoyed relative “equality” in the more-privileged private schools later faced the reality of the public universities’ unfortunate favoritism toward Muslim graduate students and faculty, and discrimination against their Christian counterparts, shattering dreams like mine to pursue graduate studies. It became clear that our country undermined our hopes and academic achievements and exiled us: emigrating to a Western country became almost every Copt’s dream.

As a US immigrant who enjoyed the equal opportunity of earning a graduate degree, teaching in American institutions, and participating as a naturalized citizen in electing my leaders – all privileges that were strange to me in Egypt – I call the US home, a term I never savored until I distanced myself from my country of birth that othered me in many ways.

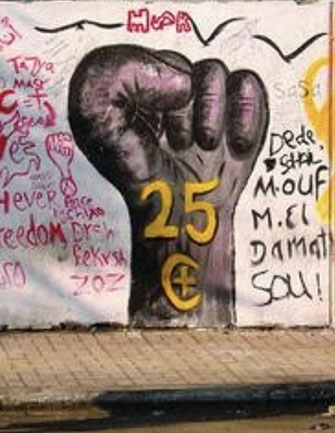

Black Lives Matter resonated around the world, igniting discussions of social justice, equity, and inclusion. In reflecting back on the reasons why minority Copts have not voiced their opposition to inequality and exclusion, one must allude to what has become a normalization of their undermined status since the Ottoman millet system and under British colonial rule. Colonialism deepened divisiveness among citizens of the colonized Arab states “based on a differentiation of citizen rights in various categories, depending on people’s cultural assimilation, religion, ethnicity, and especially loyalty,” creating a sort of “foreign patronage” of Christians. Nonetheless, in their rise against British colonialism, Copts united with Muslims during the 1919 revolution under the slogan “Religion is for God and the nation for all” and were careful to express their loyalty and nationalism. Saba Mahmoud rightly observes in her essay, “Religious Freedom, the Minority Question, and Geopolitics in the Middle East,” that Copts refused for a long time to be called aqalliya or minority in favor of being considered equal citizens. One important shortcoming of this resolve to not challenge national unity and to convey the illusionary image of their equality to the majority was their social exclusion, consequently overlooking their concerns. As Vivian Ibrahim argues in “Beyond the Cross and the Crescent: Plural Identities, and the Copts in Contemporary Egypt,” “the rhetoric of Muslim-Coptic union has played an important and reoccurring role in the memory and imaginary of who was an ‘authentic Egyptian,’ subsuming minority rights to a question of ‘Egyptian rights.’”

Egyptian national media perpetrated such exclusion. Prior to the revolution of satellite dishes, Egyptian society was seen through the lens of its only three national television channels. Copts’ representation was restricted to minor, insignificant roles in television or cinematic works. While Egyptian cinema embarked on tackling many critical social problems like drug addiction and terrorism that crippled society from the 1980s to the 2000s, it insisted on keeping its largest minority invisible on the pretext of a fear of sectarianism and out of its desire to convey an image of co-existence. Young film director Amr Salama’s Excuse My French (2014) made history in Egyptian cinema, following a four-year battle with censorship and five rejections of his script, for detailing a Christian boy’s daily struggle to fit into a Muslim-majority public school. Literary works afforded more freedom due to their limited accessibility and readership and smaller impact on societal changes. Laila Farid’s “Copts in Modern Egyptian Literature” surveys the many literary publications on Copts.

Often characterized by their submissive meekness, Copts had to accept their exclusion and institutional discrimination, finding comfort in the belief in the reward of forgiveness, of turning the left check to those who slap them on the right one. Self-consolation with such a reward that awaits was all that they had, since authoritarian governments coerced for so long the Coptic Orthodox Church into silence in return for protection and security. The church-state entente began with Gamal Adbel Nasser who ruled with an iron fist; his successors followed suit. Anwar Sadat set the tone of expectations of the Coptic papacy by sending the patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church Pope Shenouda III into exile in a monastery in 1981 for accusing Sadat of failing to control Islamist groups (the Pope was not released until

Mubarak took office in 1983 following Sadat’s assassination, which many Copts still dub God’s punishment for the Pope’s exile). Three decades later, when protestors took to the streets in the January 25th revolution of 2011, demanding an end to Mubarak’s authoritarian rule, Pope Shenouda III who died March 17, 2012, warned Copts not to participate and pledged the church’s support of President Mubarak as its guardian, which many Copts viewed as a wise step in face of the unknown. Of course, Mubarak was ousted, and many sectarian incidents erupted even before the first Islamist president Mohamed Morsi took office. Hoping for less bloodshed, they supported the 2019 amendment to the constitution that extended Al Sisi’s presidency until 2034 as he vowed their protection “from the evil powers of the Muslim Brothers and other terrorist groups,” establishing with them a relation of loyalty.

Undoubtedly, growing up in a collective society of expectations and outcomes has challenged the upbringing of a Copt in Egypt. Adding to the internal pressure by the community’s faith-related practices and the relation to the larger Muslim majority, radicals, and the state, recent global debates about race have given rise to the Copts’ consciousness of their ethno-racial identity and the need to fit into a racial classification, traditionally an uncommon issue of discussion in Egypt. This need has yielded an ambivalence of self-identification as white, brown, or black among Copts.

My imagined identity celebrates its unique ethnicity and rejects any societal judgment founded on faith, so-called moral standards, dress code, skin color, hair texture or color, race, or any stereotype or element that subjugates its freedom.