“From border control to taxi driver, to strangers at a party, my reverse-migration appeared to satisfy a sacred narrative: the prodigal offspring returns to her rightful home. But it was never so obvious for me.” Amelia Izmanki traces her Lebanese family’s history from the beginning of the 20th century to find her own way back home.

Of the four teenagers who watched Lebanon sink into the horizon that day, only one, my great grandfather, Ghanem, would see it rise again from the sea.

Two couples, Miriam and Ghanem, Anthony and Jennie, had descended from their mountain village of Bziza to board a ship bound for Ellis Island. The marriages, arranged by their families, had undergone a reconfiguration, the deals brokered by their parents having deferred their authority to pubescent lust. Anthony, intended for Miriam, instead fell for Jennie, whose subsequent pregnancy brought all parties back to the negotiating table. Ghanem, Anthony’s younger brother, was offered up as his replacement to appease Miriam’s jilted family.

As the coastline receded into the distance, Mount Lebanon’s serrated edge now barely troubling the line between sky and water, Miriam leaned against the ship’s railing and contemplated her future husband. The 15-year-old boy, four years her junior, sat on a bench further down the deck, hunched over, elbows resting on his knees, intently twisting the frayed edges of his jacket sleeves. It both irritated and softened her, how he imitated the voices and gestures of the village men but still looked like a child.

It was 1901 and Ghanem was as old as the Statue of Liberty.

They docked in New York, arriving to the permanent smell of fumes from the foundry where they worked and to the house where they would soon be joined by four more immigrants from Lebanon. Some years later, after three children had been added to the household, the building crumbled in a storm, ejecting all 11 people out onto the street. The two couples, eager to finally put an end to their embarrassing proximity, set off in opposition directions: Ghanem and Miriam to southern Ontario, Anthony and Jennie to Cuba.

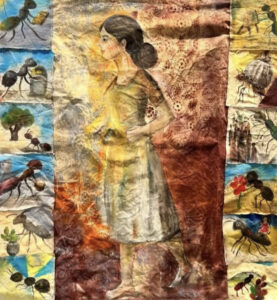

Over the course of the next decade, mostly spent in the town of Kitchener, Miriam would birth five children. Her fifth and final child came into the world as starvation set in back home. The people of the mountain had been cut off from the west by the French and British, who blockaded the Mediterranean, and from the north and east by Ottomans, who confiscated all the available food from Syria as well as whatever people managed to grow locally in order to feed their army. Mount Lebanon was isolated from the world: nothing went in and nothing came out. Not even news of the living skeletons and their slow, aching deaths.

While Ghanem’s growing family in the West sat at tables filled with Lebanese dishes, those edible hymns of home, back in the village to which they raised their glasses, there was not a grain left to eat. Only two Bziza relatives survived, and only one of the two made it out, arriving in the States with stories of death on her lips. After that, no one spoke of famine, and they no longer waited for letters in the mail.

Ghanem became the Man of Many Names, picking a new one every time someone asked. He reinvented himself on each new official document, turning his life into a kaleidoscope of identities. Perhaps it was a reaction to hearing the earthy tones of his given name flattened by English tongues one too many times, for over the years, the guttural strength of “Ghanem” had been reshaped into innumerable shallow utterances: Jake, Jacob, Jacobum, James, John, and even, somehow, Joanne.

Miriam became the Mother of Five: four daughters and one son, my grandfather. The girls, unlike their determinedly good-natured brother, didn’t like their father and had no qualms about making it known. Ghanem’s success as a grocer bought the family a storm-sturdy house, but he’d gone to live with his mistress instead, a woman named Annie from another local Lebanese immigrant family. She took each of his names very seriously, waking up in the morning and asking, “And who are you today, my love?”

As it turns out, Annie was Ghanem’s cousin, but cousin or no, his attentive mistress eventually left the dull Ontario boulevards for her native Koura’s endless orchards. Desperate to follow but yet unable to afford it, Ghanem bided his time through the Great Depression, opening a second grocery store (people still needed to eat), and eventually selling the first to buy himself a return ticket to Lebanon, where he reunited with Annie and brought her to live with him in his beloved Bziza.

Miriam stayed in Kitchener, where her children and her garden both grew with ferocity. Somewhere along the way, her distance from Lebanon had become insurmountable — at least physically. She never said she missed home, but she didn’t need to. She’d sit at the kitchen table listening to her children read letters from Bziza aloud: “That’s all the news I have for now. Kindly send money. Ghanem.” And then she’d get up and lower the needle on the record that never left the gramophone. She’d stir the air with her hips as music from home rushed into the room, swirling the kitchen away and parting open a view onto the olive-dotted hills that framed her village. The road from her family’s house to the river unravelled at her feet; a pomegranate tree dipped down from overhead. By the time my dad, the toddler too young to stay home by himself, arrived from kindergarten, the record was long over, but Miriam would still be singing along.

Often, after everyone was asleep, she’d sit in front of the silent gramophone, still hearing the music, and try the journey in her head. She’d play through the motions: packing her bags (how many? Would one be enough? She could never carry more), driving into Toronto’s restless downtown, boarding the train to New York City, finding a cab to the port, and then… and then…. No, she couldn’t do it. She’d argue with herself long into the night: the children would have to come, but they didn’t know Bziza, they’d never seen its benevolent hills and all the things that grow on them. Kitchener was their home. No, this was a home, but if they saw those hills, sat under a canopy of olive branches, the sun stretching its fingers through the cracks, laying little kisses on their faces… they would understand, that was their true home. Then she would get up, straighten her dress, survey her garden from the back window, as if harvesting strength from its moon-dipped foliage, and try again. But even in her imagination she never made it past the port. Even in her imagination the journey from her bedroom to the water’s edge was too arduous, and the idea of leaving her children behind threatened to stop her heart. No, home was lost to her. That home at least.

Twenty years later, Ghanem came back to Canada. His family had stopped sending him money and so he’d come to take it from them himself. The store at Five Points was thriving under his children’s guardianship and he figured he deserved some of the cut. He moved into the big house with Miriam, who spent most of her time tending to the garden that gave her everything she ever put on the table, except rice and meat. The children were grown, some with spouses, some with children, and some neither. On spring and summer Sundays they’d sit in lawn chairs on the one patch of grass not given over to cultivation and eat feasts made out of the fresh harvest. Bess gave her father hell, Liz and Anne tolerated him, and Amelia, the great aunt who gave me her name, ignored him. My grandfather Joseph, as always, sought the middle ground.

Ghanem went to church every morning where his only son’s eldest son was an altar boy. That boy, my father, watched his grandfather intently. His pious face stood out in the sea of pious faces: his eyes were the only ones that remained closed throughout the service. Perhaps he prayed so hard his eyes forgot their worldly purpose. Every day he spoke to God and every day the mist seeped more thickly beneath his eyelids until, one day, he opened his eyes to find his pupils entirely clouded, the fog too thick to see through. It was this country they call Canada, with its diluted skies and lazy landscapes, he thought. It had done this to him. He was sure Lebanon would fix him; it was the source of his body and therefore its custodian.

He returned immediately, and after two cataract surgeries and 15 days in a Beirut hospital, he could see clearly again. He then ascended to Bziza clear-eyed and triumphant; Lebanon had fixed him; Lebanon was all he needed. In the village, they celebrated this affirmation with a feast. His stomach heavy with familiar food, he fell from his chair, one hand full of grapes like a rosy-cheeked deity, and never got up.

I imagine it this way: he had never wanted to leave Bziza, and while he was away, he wooed the village from afar in every way he knew how. He made money — first in the foundry and then as a peddler and eventually with voluptuous fruit stands — just so he could spend lavishly on her upon his return. He wrote to her, clumsy sonnets and trite phrases extolling her “purity:” her untouched trees and soft curvaceous hills, the modest, demure river that wandered politely through her valleys. Whenever the coffers allowed, he bounded back into her forever-open arms. Now he was the man from the West, with an answer for everything, far from the life he’d been forced into by his older brother’s wandering intentions. And he laughed like he never had in Canada and he ate and he drank and he smoked because he was already in heaven, and Bziza was in love with how happy he was and she brought him more food and more drink and laid his cigarettes out for him on a platter, and she clapped her hands gleefully at the one who had returned because he couldn’t stand being away from her and the excitement swelled in her until she couldn’t hold it back and she wanted him inside of her so she opened a hole in her earth and swallowed him whole and they became one.

His children received the notice of his death — accompanied by a request for funeral funds. His daughter-in-law, my grandmother, quietly squeezed kibbe into shape with her hands as her husband, a man who had never seen and never would see the shores or snow-dressed peaks of Lebanon, printed a letter in neat Arabic to send with the money they were wiring to pay back the expense of burying his father’s body.

And then, 55 years of silence. Kitchener and Bziza, two separate planets orbiting in complete ignorance of one another. But what the village didn’t know was that Ghanem and Miriam’s grandchildren had started patching together the frayed tapestry of their family history. My father and uncle went back to the beginning, tracing the threads of immigration. They followed Ghanem from name to name, and Miriam’s attempts to navigate the grueling Canadian bureaucracy after his death. They scoured archives and small-town histories, combed through their childhood memories for clues, then called their cousins to do the same. Fifty-five years after Bziza stopped her lover’s heart before the West had another chance to take him away again, so she could lie with him forever, my dad, his brother and I finally arrived in the room where Ghanem had died. Peter, the grandson of Miriam’s brother (the one famine survivor who stayed behind), pointed to the fridge in the corner. “That’s where it happened,” he said. “Ghanem fell, right there.”

Everywhere we went, I watched my dad take in every detail. He inventoried each leaf, every archway, every fruit stall and low stone wall, every orchard, trellis, pine cone, coffee cup, tile. He devoured landscapes as if trying to make up for both his and his father’s absence. He saw every plant through the eyes of his grandmother Miriam, who had tended the Canadian soil as though it was a portal to the land she’d been born on. He looked for himself in the men that he met, to see perhaps if, through them, he could imagine a parallel life for himself, one where he’d been born in his ancestral homeland instead.

The Prodigal Return

Five years after that too-short visit, and after one too many tussles with Toronto’s cannibalistic rental market, I put all my belongings into boxes, including Miriam’s salmon-coloured mixing bowls and the glass double-boiler my grandma had used for making laban, and stored them away. I packed one big suitcase for my own transatlantic voyage. It seems a part of me had always known I’d move to Lebanon. I don’t remember deciding — only having decided. There was, in a way, a sense of justice to it, feeling like I was somehow “putting things right.” And then there was the thought that I didn’t want to die without feeling the world in my bones.

At the airport, I crossed the passengers-only threshold wondering if my dad’s eyes were watering because of the jokes I’d cracked to try to soften the departure, or if he was truly crying, the way I was trying not to. The fact that he wasn’t coming to Lebanon with me felt impossibly wrong. I left my family behind the way Miriam could not, and I was plagued with the remorse she had perhaps wisely avoided.

I quickly found an apartment in Beirut, bare except for a six-burner stove that spoke to me of feeding many mouths. Sixty years after Ghanem fell from his chair, I went to the used furniture warehouse in Furn el Shebbak to find a chair of my own. I never got any better at answering the question: “What are you doing here?” The surest way of ending an interrogation was to simply say, “Well, my dad’s side is Lebanese.” It didn’t matter that they’d left before Lebanon was even a country. From border control, to taxi driver, to strangers at a party, my reverse-migration appeared to satisfy a sacred narrative: the prodigal offspring returns to her rightful home. But it was never so obvious for me.

I can imagine Ghanem puffing his chest in pride at news of his descendants pursuing his trail. From Miriam, I think my choices would have garnered a wistful silence born from the overwhelming awareness of life’s infinite complexities.

A year later, I planned my first visit back to Canada for Christmas, but less than two weeks before I arrived, the home I’d grown up in, the home where my parents still lived and where we all would have spent the holidays together, burned down in a fire. I returned to a mangled blackness that crunched under my feet. The rooms looked like a macabre replica of themselves, a cruel and fetid shadow of all our memories: 28 years of my own, 35 years of my mother’s. That Christmas, before the men in big boots came to tear what was left of the house down to the studs, my parents, sibling and I sifted through the ashes for anything salvageable. We carefully scrubbed what hadn’t burned with toothbrushes and rags that blackened immediately. If only it was just the house that had burned, miraculously leaving intact all that had been inside of it. The house itself could be rebuilt nearly identically. But without Dad’s books and Mum’s carefully placed trinkets, could it ever be our home again?

People like to say that home is immaterial, that whenever you are with those you love, you are home. But does anyone really believe that? I think most people who say this have never lost or had to leave home. Don’t we all want a little square of space on this earth to which we can bind our spirits? A patch of dirt, of place, that tends to us as much as we tend to it? From the stories I hear, my grandpa, Joseph Izma, bound his spirit to the great wooden counter in the grocery store that, with him and his four sisters at the helm, was the heart, the stomach, the pleasures and the routines of the town of Kitchener, the only home they’d ever known. Miriam Andari, disappointed by every man except the one she bore, bound her spirit to the Canadian garden from which she fed her children, their spouses, and their children. And Ghanem Izma, who was never meant to leave, bound his spirit to Bziza. But must we be bound to a place to call it home? Is being unbound then a kind of homelessness?

Nearly a century and a half after those four teenagers arrived on the opposite shore, I am in Lebanon, the place they left, knocking on the doors of various vaulted archives to find proof they ever existed. I call the mukhtar in Bziza and tell him we’re trying to apply for citizenship (a token for my father, and practicality for me) and ask if he can send me all the family documents. But he tells me he has nothing to give. And at the archdiocese in Tripoli, Ghanem’s funeral notice clenched in my hand, they shake their heads. No documents, just a name scrawled on the margins of an old sheet of paper. At least, for once, it was his real name. Even if Lebanon forgets its children, its children have not forgotten it. What do we owe to those who came before us? Perhaps just to remember — even if we have to imagine most of the details for ourselves.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)