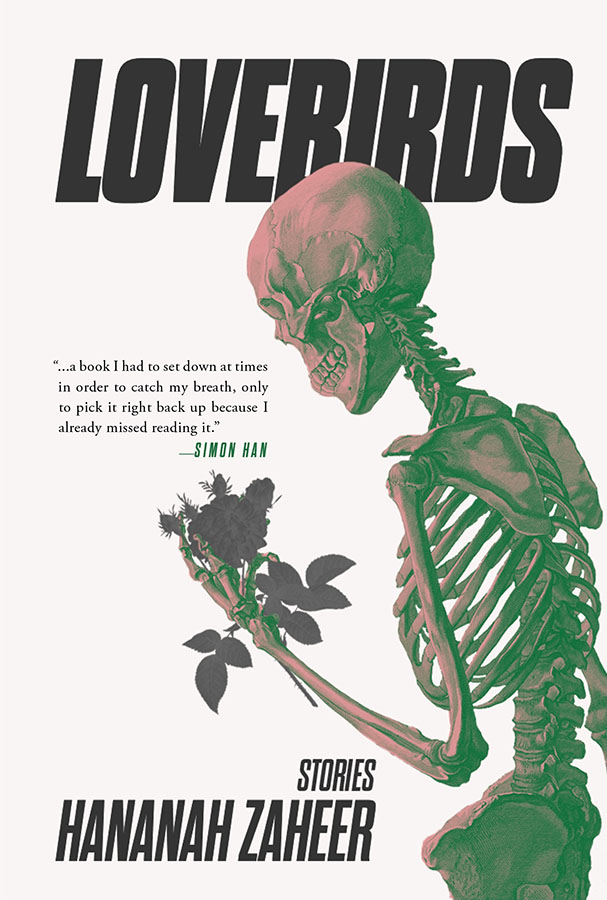

Lovebirds, stories by Hananah Zaheer

Bullcity Press (2021)

ISBN 9781949344257

Mehnaz Afridi

Pakistan has produced some world-class writers, who, with their cultural diversity and English language vibrancy, have portrayed their nation’s mindsets. Political disruptions and economic destabilization have contributed to such exemplary works as Mumtaz Shahnawaz’s Heart Divided, Bapsi Sidwa’s Ice Candy Man, and Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist. Their novels belie a thriving literary tradition in Pakistan, while abroad they have been recognized for their stunning creativity and unprecedented contribution to literature. A longer list of Pakistani writers might include Kamila Shamsie, Mohammed Hanif, Hanif Kureishi, Ayad Akhtar and Moni Mohsin, but there are many more.

Love Birds by Hananah Zaheer grips your soulful imagination in a series of short stories. Laden with themes of loss, betrayal, poverty, love, longing, immigration, family, religion, and death, this collection plays with abstract emotions and concepts in a truly enchanting way. The themes are simple but the writing is seductive because the voice of the author through the descriptive narrative is always present — talking right at us through her brief yet intense characterizations and use of symbolism. In a compact frame of words, she manages to encapsulate different themes and lure the reader into the next story. Leaving us with deep provocative feelings for the mother who has lost her child or her marriage, she also asks the reader to look for G-d in places that are unimaginable, such as a chicken coop or in humorous obsessive love.

Zaheer is a Pakistani woman like me, living in New York like me, who beckoned me to think about relationships in Pakistan in a transformative way. Pakistan’s novelists have written about immigration, racism, patriarchy, history, colonialism, and living in two worlds. However, Zaheer encapsulates all of this in a very short span: 49 pages. When one reads the first story, it is about an immigrant family, and as a reader of Pakistani literature, you might feel disappointed because a lot of Pakistani novels are about living in two worlds or challenges that one experiences as a Pakistani in the West. However, Zaheer goes on to surprise you in her other stories, for her characters and descriptive narratives hold your attention intensely.

She uses the common patriarchal stories of rejection, abuse, and neglect accompanied by the female and male voice that rejects all of this at the same time. These are the voices of women who fantasize about whether it is the loss of their child, husband, jinn, lover, killer, and a place which recasts a shadow on the inner depths of female fortitude and perseverance.

There is a loneliness about her writing that makes the objects in her short (really short) stories speak like living organisms. As you read them, you begin to see cracks in the frame of a mirror, a yellowed ankle, the neck of a little bird, and the looming sap of trees. Her descriptive narrative of objects is reminiscent of Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence (2009) in which he recreates a fantastical love story and obsession through objects and offers a new subjective meaning to them.

In the first story of Muslim immigrants longing for home and dealing with a new life, she relates the following:

“Father comes back, towel around his waist. What happened to the light? A drop of water falls from the end of his beard onto my book. I shrug and slide a needle up my sleeve. He misses the most obvious things.” (p9)

The reader sees the family relations immediately and the water falls onto the narrator’s book as she relates that he (her father) cannot see her or the most important thing which is her. Zaheer, like Pamuk, conveys the obsessive nature of love, betrayal, family, and fantasy. She has a mastery of artistic writing where the stories and objects are used as the foothold of small emotional feelings of loss and metaphysical reflections of the reality that we cannot grasp through mere storytelling. She even writes in one of her stories that, “In this way, their apartment was becoming a museum of rejection.” (p25)

Relationships are complexified in her stories with the references to Pakistani and Islamic culture, and patriarchy scrutinized. The men are always portrayed as insensitive, cheating on their wives or not being particularly smart. In one story, she relates the following as the husband witnesses a fire in their home:

“He remembers dragging her across the room. He remembers her defiant face. He remembers calling her a whore. He remembers her saying she hates him. He remembers thinking the neighbors would hear. He remembers leaving the room…He doesn’t remember what set everything on fire.” (p21)

Patriarchy is portrayed through fathers, society, religion, lovers, and marriages. Pakistan is a liberal society that is and has been run by female leaders, but the traditional customs are oppressive for women. That is why in her writings, she portrays the extremism and folklore in Pakistani society with a critique from a female perspective. Zaheer is clear about that. A second wife appears in her stories as she accepts her fate, as many have to under strict shariah laws. In her story “Love Birds” — an ironic title for a depressed and betrayed woman who receives a blue bird from her husband — “…a Happy Anniversary, darling even though it was the same year she has lost her mother and happy was the farthest thing from her mind but he had been feeling guilty, turned out, about his new, secret, wife and his affections had become louder…” (p21)

The last story is intriguing and essential; as it is written by the author through a man’s gaze, one has to keep looking back and making sure it is a male as the author thwarts your expectations so easily. “You had to be a man, be strong, in front of a face like that. That was what my father taught me” — an obsession and cruelty that she demonstrates can only come from a man.

Zaheeer also regales us with cultural and religious knowledge. In “Willow Tree Fever,” we are introduced to the concept of jinns as well-known beings that co-exist amongst humans as read in the Qur’an. Jinns are beings made from flame or air and they are capable of assuming human or animal form, at times dwelling in objects and nature including stones, trees, the earth, the air, and in fire. They have the same bodily needs as human beings, but their power is that they are free from all physical restraints. Jinns can amuse themselves by hurting humans for any harm done to them, intentionally or unintentionally. However, in Pakistan and other Islamic countries there are human beings who dedicate themselves to learning the proper spiritual prayers, diet at times, and communicate with them in ways that can exploit the jinn to their advantage. Zaheer uses the concept of jinns as they appear in one of her stories as those who take over the men in a community through the sap of a tree. This story also challenges the common perceptions of women’s roles in society, which states that women are predominantly the ones who are being overpowered or in possession of jinns.

Zaheer has offered us a short yet profound work with a critical edge that stands alone as one of the most refreshing short collections I have read. As she wrote in “God in the Chicken Coop”:

“Somewhere in the midst of the fluttering, the noise, the chickens, I think, saw it too. They calmed their desperate slams against the wall, stopped the pecking, searching for sustenance, and looked up at the sky and were still.” (p22)