Can theatre drive political change? Rarely, but it creates the conditions of possibility for achieving it.

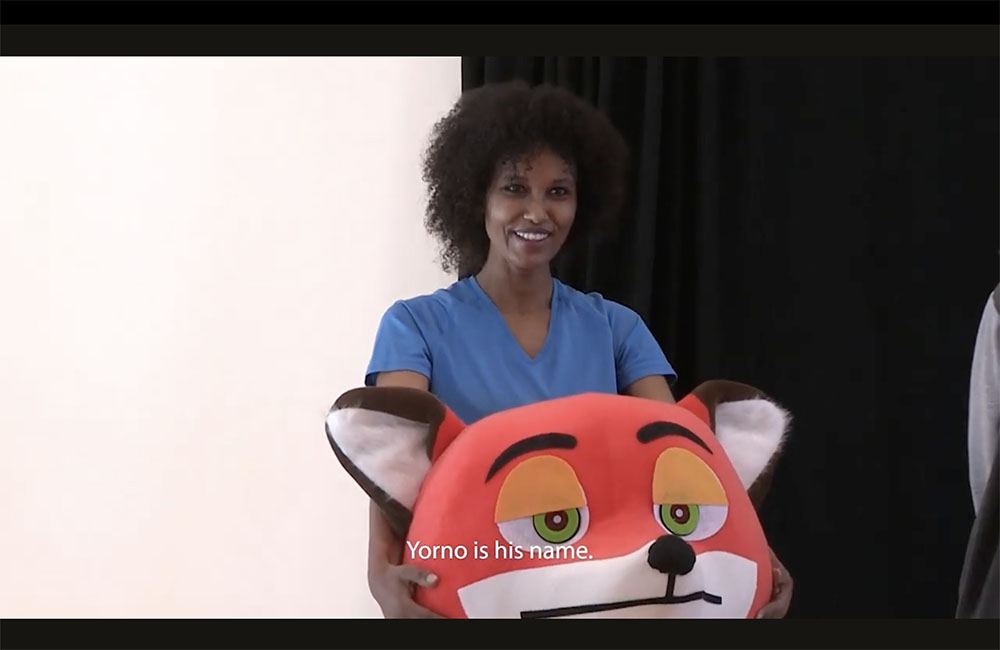

A young woman holds the giant head of an orange cartoon fox costume. Her wan smile matches that of the animal. In faltering Arabic, she explains to her fellow actors that after a year banned from contacting her son, she hid in this fox head in the hopes of seeing him at a children’s party. She scraped the money together to buy the fox, naming it “Yorno” because she would either manage to see him, or not –– Yes or No. Ultimately, her plan worked. “I was very happy and very sad at the same time,” she says of the hours she spent playing with her son. “It was hot and I was crying inside Yorno.”

This is Tima, an Ethiopian woman living in Lebanon, appearing in a scene in TILKA, a documentary film directed by Myriam Geagea. Taking its title from the Arabic word meaning “those” in the feminine, TILKA is the first film made by Seenaryo, the organization I founded which makes participatory theatre across Lebanon, Jordan and (more recently) Palestine. I have known some of these women for eight years; I produced TILKA and advised on the play of the same name whose creation the film depicts.

The film follows a group of five women as they live together in the mountains above Beirut in March 2021 while making a play. The women are not professional actors; they live in different regions of Lebanon and come from Lebanon, Syria and Ethiopia. The beautiful, calm surroundings of their temporary home at Hammana Artist House are a radical departure from routine. Of the women, two have lost custody of their children for years because of Lebanon’s sectarian custody laws, which separate divorced mothers from their sons at a young age. These same two women have also lost homes: Tima in the Beirut Port Explosion of August 2020, and Fida after fleeing a massacre of her family in Syria. Two of the women grew up in care. The final woman, Najah, has lived for eight years in a refugee camp in the Bekaa Valley; one scene is filmed in her tent. “In Hammana I had a space all for myself. Do you think there’s hot water or a shower here?”

Over two weeks of residency, and four months of rehearsal, the women tell their own stories and imagine new ones: a group try to stay silent while escaping an angry dog; a human breathes heavily in her astronaut suit in the silence of space; a woman chooses to sell her daughter at the market. (“If I sell her, they’ll take care of her. If I give her away, they won’t. I don’t want her to suffer like I suffered.”) They build their strength, learning to lift each other up — literally, as the play’s director Lama Amine is a physical theatre practitioner who trains the women to carry each other as they leap above each other’s heads and walk along walls.

They perform their piece of abstract, devised physical theatre at the end of the film to a small and socially-distanced audience: one of the reasons that the film TILKA was made was because of the pandemic’s impact on audience attendance. It began as a budgetarily constrained afterthought, simply to allow more members of these women’s communities to be able to engage with the theatre performance they devised, and was conceived as a continuation of Seenaryo’s community practice. But since premiering eight months ago, it has taken on a life of its own, winning prizes at two Beirut festivals, presented at festivals in London, Cambridge and Sheffield in the UK, with screenings planned in other countries.

The play tells the story of a group of women, one of them the Mona Lisa, who are the subjects of artworks in a museum. They escape their paintings, deciding that they must travel together to succeed in finding a better home.

In creating this piece of theatre, the women become advocates for their rights and those of women in Lebanon. Tima, hidden in her fox costume, is a stand-in for every woman in Lebanon unheard or unseen, isolated from family and homeland by political injustice. This is reflected in the characters in the play, who begin it in full face bandages, which they slowly remove from each other as they show each other their scars. Indeed, Tima hiding in Yorno seems to embody a dramatic archetype of female characters hidden behind masks. Belying the nylon and industrial stitching is a figure as powerful as Rosalind of Shakespeare’s As You Like It or Hellena from Aphra Behn’s The Rover — the masked female character, disguised to avoid political persecution and to speak truth to power. Life imitates art which imitates life, in the two-way traffic of the Seenaryo process.

The experience of being cut off from the most intimate relationships in life is at the heart of the film TILKA. At another point in the film, two young women sit on a stylish maroon sofa, a neat bookcase in the background, explaining that they have stopped waiting for their parents. Fatima — black-painted nails dancing as she turns the rings on her fingers — explains that “at 18 I decided to stop looking for them.” She is sitting with her sister Rania in Dar Al Aytam Al Islamiya, the orphanage in which she grew up. She swallows a sob as she says: “At the end of the day, when I put my head on the pillow at night I would ask myself: where are they? Inside we wanted to meet them, but we’d say to each other that we didn’t.” But this is no simple sob story: the pain of separation has also forged a sibling bond beyond the strictures of the nuclear family. Her sister Rania steps in with a wry smile and a glint in her eye: “We only wanted them if they were rich, or if they were celebrities. I would say my mother was Rihanna. Fatima’s was French: Céline Dion.”

Seenaryo’s work looks for these moments of unlikely power: imaginative leaps, wry smiles, and downright slapstick when our facilitators propose a prompt or stimulus (a poem, a theme, an image). This stimulus opens space for participants to improvise scenes together; our facilitators listen to and refine their ideas and send them back for a new round of scene-building. It’s a recursive, months-long game of creative ping-pong between the facilitators and the group that ends in a play.

Earlier in the film, we see Fida, a Syrian single mother who spent five years separated from her two daughters, hugging them both, laughing on the sofa. Echoing Tima’s smile and the glint in Rania’s eye, she says lightly: “Since we left Syria there hasn’t been a home. It ain’t home. But it’s somewhere. (Ma fī bayt. Fīsh bayt. Fī makān.)” Then she clarifies: “I dream of an ideal country, I don’t dream of an ideal home.”

What are the boundaries between private and public lives? How are they drawn by political regimes? And how do women find ways to manoeuvre around them — sometimes in disguise, sometimes strutting, often forced to seek refuge in hostile environments? In a sense, making a play answers these questions. The women seek a temporary sanctuary onstage. Theatre creates formal settings for injustices to be heard, most crucially by an audience — however small — of peers from one’s own community. And sometimes, through a national or an international tour, or even a film documenting the process that travels to audiences further afield.

Theatre is by definition ephemeral, at base a simple encounter between a community of actors speaking to a community of spectators. A documentary about a play can be quixotic — even a contradiction in terms — sidelining the final performance in favor of the process of collective creation. However, creating conditions to be heard — not necessarily removing the mask, but exploiting its ambiguity — is a fundamentally political act.

Seenaryo’s work contributes to a tradition of participatory and political theatre in Lebanon, much of which has focused on shifting the audience role from a passive to a proactive one, drawing on approaches that extend from Forum Theatre and Theatre of the Oppressed to the more recent Playback Theatre. Through these techniques the audience (“spect-actors”) are responsible for proposing ideas and intervening on the direction of the performance.

Rather than focusing on the audience’s role, Seenaryo aims to shift the actors’ role from professional performers to creators and advocates. We also train these creators to lead and facilitate the work themselves, challenging the hierarchies between writers, directors and performers by creating plays with radically inclusive creative teams that are nonetheless powerful and entertaining enough to be presented on major national stages.

There is a moment in TILKA — the film — when Rania and Fatima are in Dar Al Aytam, showing the camera the bedroom they grew up in. Suddenly, the play’s director Lama comes out from behind the camera wearing a Covid mask. “The bed Rania is sitting on, was my bed. My number was 149. They used to number all our clothes. When the washing came, they’d call: 149. I don’t know why it means something to me, but I love this number.”

“My number was 38,” says Rania. “Mine was 1,” says Fatima. “Wow,” exclaims Lama, “number 1!” In a moment, Lama’s own history becomes clear. Throughout the film we have seen her as the leader, differentiated from her cast of participants; we now understand that she grew up in the same community as many of them.

Seenaryo aims for as many of our director-facilitators as possible to come from the communities we serve (currently, around 30 of our freelance team of 100). We have just finished a project funded by UN Women (under the Women’s Peace & Humanitarian Fund) and in partnership with Syrian feminist organization Women Now for Development. After making a play as participants, 80 women received both civic and theatre leadership training. They were then funded and mentored to lead their own theatre projects. This month, Seenaryo published a handbook, “Women Leading Theatre for Change,” for other practitioners in the region to follow.

Can theatre drive political change? Sometimes it can, directly: Zeina Daccache’s play set in Lebanese prisons, 12 Angry Lebanese, and the documentary that emerged from her drama therapy process led to the implementation of Law 463 in 2009 — the reduction of sentences for good behavior. More often, theatre does not make the change itself but rather creates the conditions of possibility for achieving concrete changes in the law. Participatory theatre trains people to create through collective deliberation, and to speak in front of an audience forced to listen. There’s a reason I have friends working as theatre trainers with ministers and officials from courtrooms to parliaments to international assemblies. And just as diversity is critical to effective representation in politics, a theatre that is inclusive creates the conditions for political change. As Najah says, “I am a person who’s changing, I have changed, and I will create change.”

Theatre also does the slow, hard work of changing and challenging the preconceptions different communities hold of each other. In Seenaryo’s process, Lebanese participants from Dar al-Aytam are thrust together with Syrian and Palestinian individuals, striking up lasting friendships. In a world where so many are seen as a “burden” (as Fida says) to be dealt with through aid handouts, blithe disregard or state violence; and where populist political regimes across the world play them off against each other to stoke tensions, TILKA opens up a rare space for participation across communities of difference.

The film TILKA premiered in September 2023 where it won a prize at a festival in Beirut. The participants came to the screening, striking Instagram-ready poses on the red carpet and receiving a standing ovation. Fida and Tima brought the children from whom they had been separated for so many years. I met Karim, Tima’s son. He said he enjoyed seeing his mother in her fox costume again.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)