The place that you rip open again and again that heals is God. —Rainer Maria Rilke

Prologue by Salar Abdoh

I had escaped Los Angeles the first chance I got and tried not to look back, even though there were periods when by default I would end up there for a few weeks or months before I took off again. Reza stayed. Nearly always with our younger brother, Sid. To whom later was added Brenden, Reza’s devoted partner who was with him until Reza’s final moment in the last apartment we shared together in the theater district of Manhattan.

For Reza, LA was the distillation of the American nightmare, the country stripped to its essence where kitsch and injustice lived side by side something far more subterranean, exquisite, tragic and transcending. I would not know all of this until years later when I would periodically visit Reza to catch up on his latest plays. We would end up in haunts that on the surface were invisible. LA, I realized, was much like Tehran, another mega-city that I had returned to and had been living in for some years. These cities lived via parallels. There was the life above ground and over the facades of a Westwood, a Santa Monica or a Downtown, and then there was another world where, among other things, astonishing art happened. I was struck and awed by these polarities and finally understood why Reza thrived in LA as he did — it gave him endless material in the sprawl of its garishness and its beauties. I understood, but I still could not make my peace with LA the way Reza and Sid had. All three of us had known the hunger, the homelessness, the saw-toothed vulnerability of those early refugee years in this city. But whereas I’d walked away, griping, Reza had remained so that he could erect his craft out of the sludge of what was; he didn’t seek out or need anything more. The material was right here.

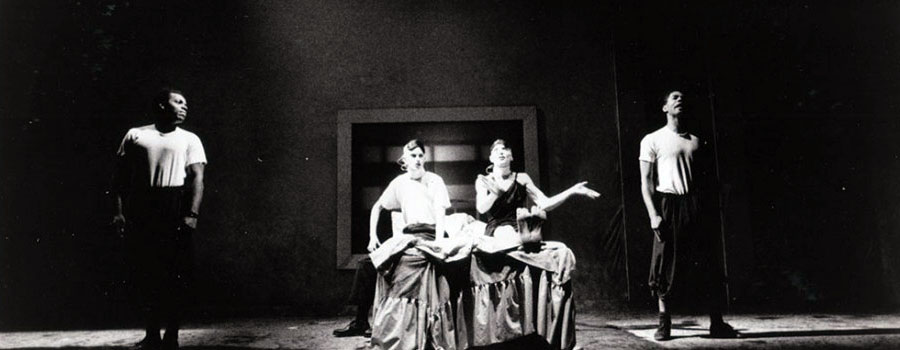

The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice was arguably the first work where Reza Abdoh crystallized his art to that point where vision and logistics could make a modicum of a shivering peace at last. Tom Fitzpatrick, Reza’s longtime actor, and Alan Mandell, the renowned Beckettian actor, were in this play. As was Juliana Francis Kelly who henceforth would become Reza’s principal actress in the legendary theater troupe, Dar A Luz, that he created.

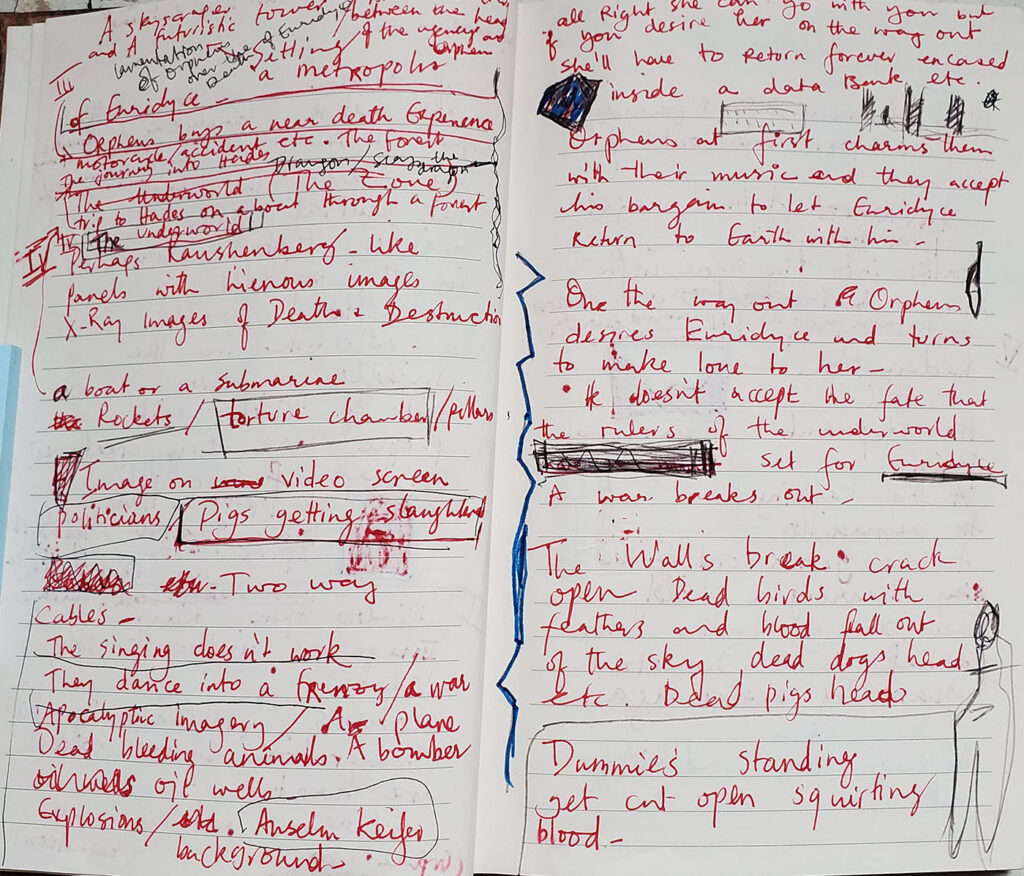

What follows is a remarkable recollection by Juliana of that moment in time in LA when Hip-Hop came into being, juxtaposed with images of original notes by Reza for the play. —Salar Abdoh

Juliana Francis Kelly

1.

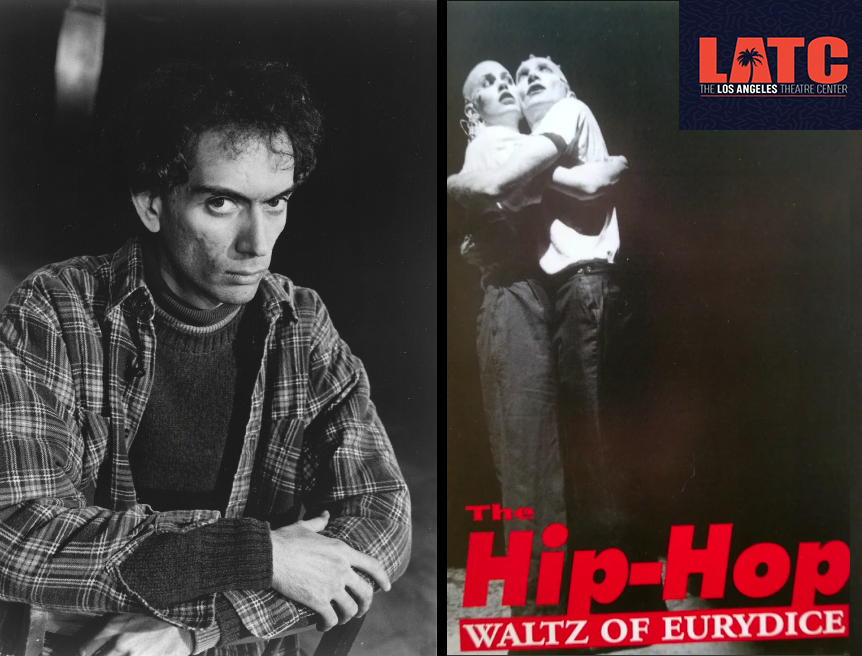

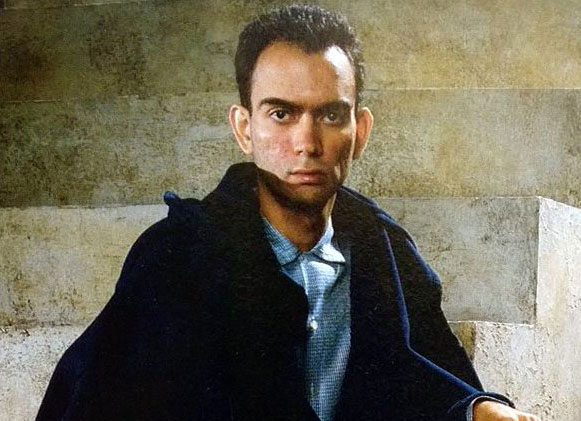

During the first week of rehearsal, a photographer from the Los Angeles Times arrived to take a portrait of Reza to accompany a profile on his work. There would be a spate of these articles over the next few years. They often included a high contrast, unsmiling photo of Reza on the set of the latest play, and were filled with phrases like: “bad boy,” “wunderkind” and “the enfant terrible of sex and death.”

The photographer asked Reza to pose in front of the floor to ceiling strips of butcher paper, on which he had written the outline of The Hip Hop Waltz of Eurydice in black Sharpie. The outline was cryptic and poetic and most of it ended up changing. It had stunned the legendary Beckett actor Alan Mandell. Alan had championed Reza’s work since he had seen Reza’s King Lear staged in a gym several years earlier. With Hip Hop he had agreed to act for Reza for the first time.

“Where’s the script?” Alan asked on the first day of rehearsal.

“This is the script,” Reza answered, pointing to the outline.

Alan looked skeptical.

But sunlight would shine through the strips of paper from about noon to three, making them look golden and more substantial than they were.

The Hip Hop Waltz of Eurydice wasn’t supposed to happen. L.A.T.C. had scheduled Reza’s epic play Bogeyman for the winter of 1990. But L.A.T.C. hit a financial snag; Bogeyman was expensive and abruptly postponed.

I sometimes wonder: was there a meeting in which Reza had come up with his vision of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth on the spot? Or was it something he had been sketching out in one of his notebooks?

I also wonder: how do I write about a play that I was in, 32 years earlier? My nerves once flashed with the play’s nerves. I memorized its bones. But I never saw its face.

Dramatis Personae

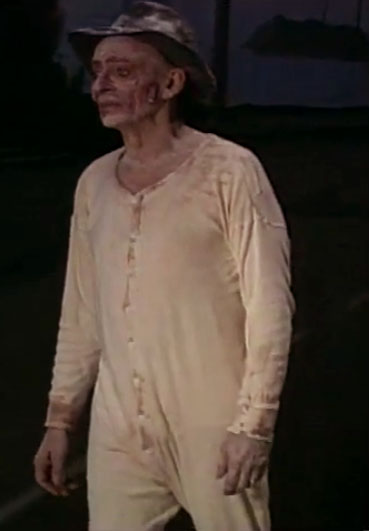

1. Alan Mandell: “The Captain.” After his initial incredulity, Alan danced through a tour de force monologue, despite being enrobed in an enormous fat suit, and a synthetic red wig, his face studded with prosthetic lesions.

2. Tom Fitzpatrick: “Eurydice.” Tom was the longest serving veteran of Reza’s plays. He was often cast as nightmarish fathers, but his Eurydice was wistful and delicate.

3. Me: “Orpheus.” I got to be a man. But I didn’t play Orpheus as a man. I just tried to fulfill the heroic actions that actresses aren’t usually asked to do.

4. Borracha: “A Hound.” A capoeira maestro from Brazil, Borracha, who as a little kid had worked as a barber on the streets of Rio. Besides co-creating the fight sequences, Borracha brought ideas for dances and clowning that Reza interlaced throughout.

5, Joselito “Amen” Santos: also “A Hound.” Borracha’s languid partner in capoeira, who transformed into a mysterious milkman in the play’s final scene.

One of a thousand things that breaks my heart about this play: much of Borracha and Amen’s performances occurred in the dimmer light cues. While they were clearly visible to the audience, the video camera often only captured a blur of movement, and the sparks flying off their machetes.

2.

I wasn’t the first choice to play Orpheus. A handsome actor/singer/dancer who had played a mercury poisoned four-year-old girl in Reza’s Minamata had been cast. But this actor withdrew; the back to back shows he’d done for Reza had taken a toll and he needed a break.

I’d only done one of Reza’s shows before: Father Was a Peculiar Man, his New York debut. I was less than a year out of acting college, and I’d quit my support job (dancing in one of the last of the old, colossal drink hustle bars in Times Square) for the chance to perform all summer for free in Reza’s take on Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. I joined a 50-person cast on four filthy, cobblestoned blocks in the not yet gentrified meatpacking district. By the time the show opened, I was entranced by Reza’s work, and so broke I had to dig out the big old raincoat I’d used in college to shoplift food. The inside of the coat’s pockets were conveniently shredded. I’d head to a grocery store, pick up a small round of cheese, a packet of crackers or a Swiss chocolate bar, and pull my arm up into the wide sleeve so both my hand and the cheese/crackers/chocolate disappeared. I’d slip my hand inside the shattered pocket, and let my next meal drop softly into the coat’s lining.

I rarely spoke to Reza during Father… He was busy. I was shy. But on the day we closed, I worked up the nerve to phone him and ask if he could recommend any Brecht poems for an audition I was thinking of attending.

“Come to our apartment tomorrow before we leave,” Reza said.

This startled me. I thought he’d just suggest a title to search for. The next day I turned up to the artist housing Reza had been sharing with his partner Brenden for the duration of the gig. Suitcases, books, and boxes were strewn everywhere.

“I hate packing,” Reza said, smiling faintly. “I can never do it.”

I sat down on the artist housing sofa. Reza left the room then returned with a packet of photocopied Brecht poems.

“I think these are good poems for you,” he said. “Read the first one.”

The poem in my lap looked like a list, not a poem. I started reading.

“1. At night I am woken up, bathed in sweat, by a cough which strangles me. My room is too small. It is full of archangels…”

Vision in White would end The Hip Hop Waltz of Eurydice. Alan’s vanquished Captain, stripped of his fat suit and his garish wig, shuffled on the longest fadeout of lights I’ve ever seen. Wearing shabby long underwear and a fedora frosted with ice, he recited the full poem over a sound cue of howling dogs and an old English music hall song, “On Mother Kelly’s doorstep, down Paradise Row…” that sounded like it was being sung by a dying man.

3.

We entered “tech,” the final days of rehearsal that stretch to 12 hours so the stage manager and the designers can test the set pieces and build hundreds of sound and light cues. Tech is an exhausting but dreamlike place. During tech, I wrote my initials on the upstage side of the set. I’d had a high school sweetheart who’d been jailed more than once. The first time, he wrote his name on the wall, and an older prisoner told him that writing your name on the wall meant you’d sealed your fate: you’d be back.

I never wanted to leave this theater, so I figured it was worth a shot.

Tom Fitzpatrick and I had both shaved our heads by then to show how light would bounce off our white makeup smeared scalps. (By the end of the run, coached by former child barber Borracha, I got ridiculously fast at shaving. I’d sit on my dressing room counter and tear at my head with a dry razor.)

Tech ended. We started previews: two weeks of public performances with rehearsals during the day to continue shaping the play.

After a Tuesday night show, Reza and Brenden came to my dressing room. Reza had notes.

Reza always had notes. He’d watch every show, pacing in the dark behind the last row of seats, sometimes chewing on the back of his hand. Stage managers had to keep an eye on him before shows began, as he’d often head backstage to give an actor a note minutes before the first entrance without telling anyone else. If the actor took the note no one else knew about, things could go badly wrong.

Before Reza took out his notebook, Brenden sat down on the edge of the regulation Actors Equity cot, and said, “You are going to be on the cover of American Theater Magazine! They are doing a feature about the show.”

I embraced them both, taking care not to smear white makeup on their shoulders. Then I blurted out a plan I’d come up with the week before.

“Hey… if this sounds like something you would like — I thought I could have a baby for you. That could be really cool, yes?”

It made perfect sense to me. I had always wanted to be a mom. And this would be a theater baby. We could take this baby on the road to all the theaters and festivals that were glimmering on the horizon, these fantastical places that would invite this play and the next play and the one after that to triumph here, there, and everywhere. Heck, the baby could be in all the shows too. What a life.

Reza and Brenden listened politely to my plan. Reza didn’t say anything and Brenden nodded. So I shut up about the baby. But I continued imagining it. I’d conjure its warmth on my chest after every show.

4.

“Our” issue of American Theater would be released on opening night.

Reza and Brenden hosted a party in their Venice Beach townhouse, two blocks from the Pacific Ocean. The sky was black and starless, the air was cool and smelled of eucalyptus leaves. The cast and crew were giddy. It had been so hard, and we’d pulled it off. Excluding our two treasures, Alan and Tom, almost all of us were in our early twenties. Stupidly young and completely unprepared for what was headed for us.

At the party, we danced like fiends to “Groove is in the Heart” by Dee-Lite.

DJ Soul was on a roll

I’ve been told he can’t be sold

He’s not vicious or malicious

Just de-lovely and delicious

I couldn’t ask for another

Before I flung myself fully into dancing, I slipped by Reza to get a bottle of seltzer water. An important looking guy had just buttonholed him, presumably to share his thoughts about the play. The important looking guy noticed me.

“Juliana!” He said my name like he already knew me and was swinging open the door to some fancy estate he owned in some fancy ass place.

Reza introduced us. The man was a playwright. I waited for him to say something nice about the performance. But instead, he turned to Reza.

“I want her for my next play.” The playwright said.

“Well — you can’t have her.” Reza answered.

“Excuse me, I really like this song, so… Nice to meet you!” I beamed my widest Times Square drink hustle bar smile at the playwright and escaped.

Two hours later, we dancers were sweaty and delirious, stomping around to “Pump up the Jam” when someone carried in a stack of the American Theater magazine.

“The MAGAZINE is here!” someone shrieked.

We raced to the stack. Raul, who had designed the sound, took out a pen knife and cut away the plastic ties. Everyone grabbed a copy.

“I look FUCKING CROSS EYED!” I yelled.

I found the article. It seemed briefer than I thought a cover story should be. I began reading in the dim light, the music still banging on: “Make My Day /Make My Day/ Make My Day…”

That’s when I read it.

“I am an artist living with AIDS.”

5.

We performed The Hip Hop Waltz of Eurydice for six more weeks in Los Angeles. I never spoke to Reza or Brenden about the article. But the sentence “I am an artist living with AIDS” lived in the air above my head like an echelon of birds.

Less than four years later, after we had been to all of the festivals, formed a company and made more shows, after I failed to perform in Reza’s last two plays, I signed on for the final one: A Story of Infamy. Reza was gravely ill by that time. But I believed with all my stupid heart that if I did a good enough job in that play, he might decide not to die.

Reza was placed on life support on the first day of rehearsal. The show was cancelled. The actors were paid through the week and sent home.

I visited Reza in the hospital. Brenden and Tom were there. I watched Reza’s chest rise and fall with the breathing machine. I grasped his thin feet and whispered “hello.” Reza seemed restless, so Brenden handed him a small notebook and a pen. Reza wrote some things I couldn’t read, and one word that I could: “Italy.”

I got to tell him about this episode a week later, when I visited him at home after he’d been released from the hospital.

“Really?” he said.

Four weeks later, he was gone.

6.

If I think back (though it isn’t really “back” — it’s more like slipping into a world that runs parallel to this one) I can find one moment in each show that I believe gave Reza real joy. In Hip-Hop Waltz… this moment arrived around week four.

We were already in the theater, a day or two before tech, but already working with some of the set pieces and sound cues. Borracha, Amen, Tom and I were running a sequence in which the set transformed from a midcentury American bedroom into a mysterious cityscape, filled with thin, abstracted skyscrapers that we rolled on and off as Eurydice was dragged into Hell. As Eurydice disappeared, I grabbed a hammer, swung it through the air at Borracha.

We stop, stare at each other, I retreat without harming him. Alan enters as the Captain and Hell triumphs.

Reza had set a cue for the sequence: industrial music punctuated by Orpheus and Eurydice’s panicked breathing. We ran the sequence again and again. Reza seemed restless. Then he suddenly ducked down, pulled a CD with a Post-it note stuck on it from his bag, and yelled:

“Raul! Can you add this to the part with the hammer?”

Raul came down from the booth, got the CD, then returned to cue it up.

“From near the end please, where Juliana first gets the hammer.” Reza called to us onstage.

I grabbed the hammer and began swinging it as I moved towards Borracha. The industrial soundscape receded and a thread of Mozart’s Requiem snaked in. Borracha leapt out in then out of a headstand, we hit our marks, and stared at each other.

The Mozart changed everything. The moment became complete, a world onto itself, filled with a terrible, angelic beauty that reflected the shards of Rilke Reza had painstakingly placed throughout the play.

Reza was thrilled.