A major exhibition at Mimosa House, in London until mid-December 2024, aims to address what is identified as urgent, pressing and unresolved issues faced by women, queer, and trans people across the world. Its current iteration is transfeminisms Chapter II: Radical Imaginations 15 May—29 June 2024.

Fari Bradley

The provocatively titled transfeminisms [sic] unfolds as a series of exhibitions, each one a “chapter.” The first, “Activism and Resistance,” features works involving a form of either private or public protest by both established and emerging artists. Zainab Fasiki, Kyuri Jeon, Alex Martinis Roe, Fatima Mazmouz, Ada Pinkston, Bahia Shehab, and Lorena Wolffer are mostly shown in the UK for the first time, with works that range from photographs of interventions and performances, to viral protest graffiti, manifestos, and video and wall pieces. Themes in the show are freedom of speech, sexual and reproductive freedom and equalities, and emancipation from both state violence and Western colonization. All of them seek space within the public arena with which to push back against the fixed ideas that confine the gendered other.

Curated by Christine Eyene, Daria Khan, Jennifer McCabe, and Maura Reilly, the series grapple with the ever expanding and self-defining idea of what feminism and indeed femininity might be. Daria Khan points out that not all the artists in the exhibition identify as women:

They embody a feminism that is inclusive and diverse, hence the plural “transfeminisms” in the exhibition’s title. Over the course of five chapters, the exhibition unfolds, allowing the audience to cultivate their own understanding of what feminism signifies. The featured works delve into themes of care, collective resistance, radical imaginations, undervalued labors, and fundamental human rights, all while highlighting the critical need for ongoing battle.

Feminism has been undergoing a constant redefinition. However it feels strange to have women’s issues described as “urgent” in the exhibition text. Women mostly put their own problems on the back burner, writing them off as simply part of “life.” Generally speaking, transwomen and the gendered “others” often consider larger issues as “urgent” compared to their own. Still, the exhibition rightly points out that women are suffering and dying due to the status quo. Whether they perceive the challenges and the dangers they face as gender-related or not, the sense of urgency is often obscured by perceptions of scale.

The microcosmic and hyper-local are pointedly explored in transfeminisms. Kyuri Jeon’s film Born, Unborn and Born Again (2020) highlights the Korean phenomenon of the “Year of the White Horse,” a misogynistic belief that contributed to the killing of unborn girls gestating in that year. Born in the “Year of the White Horse” herself, Jeon discusses how she survived pregnancy on a call with her mother, her personal narrative unfolding during protest movements in South Korea that led finally to the decriminalization of abortion in 2019.

transfeminisms illustrates how, as the gendered “other,” much of what is carried or is a burden is inherited. This is explored through photographs of interventions around public monuments, video diaries, drawing, and collage, expressing the ways in which women are the crucibles into which the world pours its ash. Women make the world, they’re burned by it, they watch it burn and yet they remake it from embers. How do they continue while also resisting?

Resistance, the major theme of this chapter of the exhibition, could be perceived as the resistance of definition: being boxed in both physically and in terms of worth, resistance to abuse and oppression, to femicide, to objectification, to being streamlined within the suffocating corsetry of beauty’s traditional ideals. Within the theme of resistance, the show goes further to propose the means for collective action, and intends to provoke the radical imagination “in order to generate a more equitable future.”

The gallery’s only window is covered in protest graffiti, six graffiti works by Egyptian multidisciplinary artist and activist Bahia Shehab from the project, “A Thousand Times No” (2010-present). The artist collected 1,000 historical versions of the letterform meaning “No” in Arabic, from Spain to the borders of China, in order to illustrate the colloquial Arabic expression: “No, and a thousand times no!”

Initially produced as an art installation and book, the project was propelled into the streets by the 2011 Egyptian uprising when Shehab began spraying the phrase “No to military rule” in the streets saying no to dictators (“no to a new pharaoh”) and no to violence (“no to blinding heroes”) in response to the unbelievable violence enacted by the Egyptian state on peaceful protestors. Later the symbols expanded internationally via a series of graffiti interventions into public spaces. The work proclaims freedom of expression within Islamic art; it challenges dictatorship, military rule, and state-sponsored violence. For transfeminisms, Shehab responded to hyper-contemporary events and designed a new no, namely “No to Genocide.” Her work is so inspiring, one comes away wishing the graffiti had been made available as stickers, even as stencils, so that the message could be taken beyond the exhibition walls.

One of the events around the exhibition’s “Chapter 1” was Cameroon-born Christine Eyene’s curator’s talk in which she described her long and prestigious journey towards a feminist curation. Eyene drew a pathway from her mother, a successful singer and performer in Cameroon, to a 1980s female artist’s self-organized show, building life-long collaborations with artists such as Sonia Boyce and Bisi Silva (1962–2019). Eyene opened with her interest in forming cultural identity through music, dance and sounds; namely language even or especially when a person from a particular country or family culture cannot speak the language. This gave Eyene a desire and vantage point to some extent to get closer to the building blocks of identity formation. In Cameroon the policing of dance forms by colonial anthropologists and commentators led Eyene to focus on themes of womanhood, matrescence (i.e. the process of becoming a mother), protest and identity.

Eyene showed two early, large photographs by Ada Pinkston, included in transfeminisms. “Landmarked” series (2018) feature the artist performing on vacant plinths where Confederate (pro-slavery) monuments previously stood, in Baltimore, Maryland. Through this work, Pinkston activates empty spaces she views as metaphors of the silences within history that belie injustice. Pinkston’s video “LandMarked Part 5: A Tribute to Fannie Lou Hamer” (2018-2022) captures a live performance by Pinkston on one such landmark, accompanied by a famous 1971 speech of Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977), the prominent African American voting and women’s rights activist who herself was a victim of state-forced sterilization.

The exhibition’s chapters also create space for London communities to contribute to the show. Lorena Wolffer’s text-based work “Públicas” (2023–present) is a manifesto to foster equal rights and access for women and LGBTQIA+ individuals. For this, the artist collaborated with community groups in London using an online survey that asked participants to identify oppressive social rules and propose egalitarian alternatives.

Mimosa House curator Daria Khan tells me: “A series of new, collectively-crafted social contracts challenge cis-hetero-patriarchal norms and imagine safer, more inclusive public environments and work conditions.”

In the same vein “Queering the Public Space” is a walking tour covering historical and contemporary sites of queer representation, activism, and resistance in London’s Camden borough, the location of Mimosa House. Guided by Dr. Pippa Catterall, a professor of history and policy at the University of Westminster, the walking tour is an opportunity to explore alternative histories surrounding Mimosa House, in connection with the current exhibition.

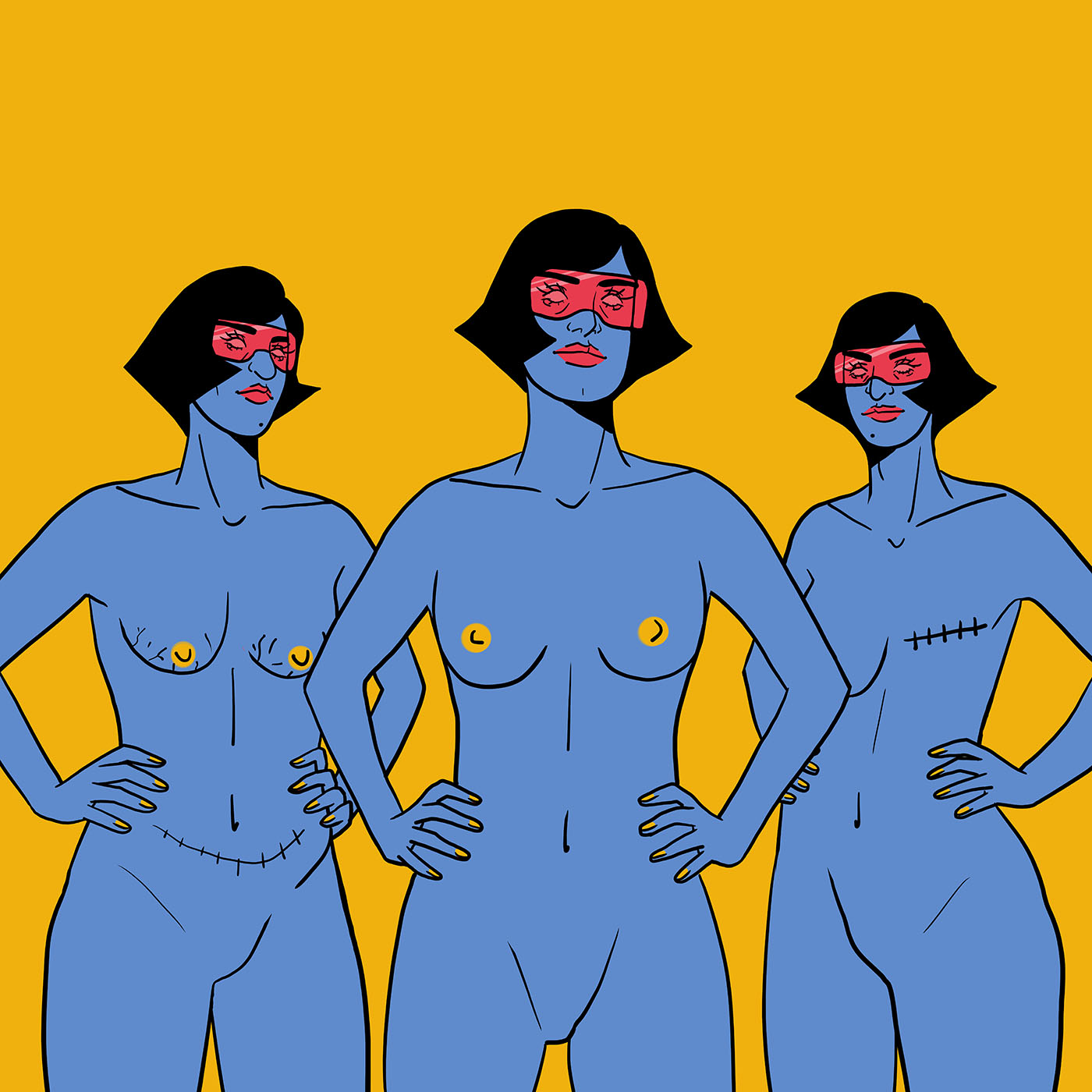

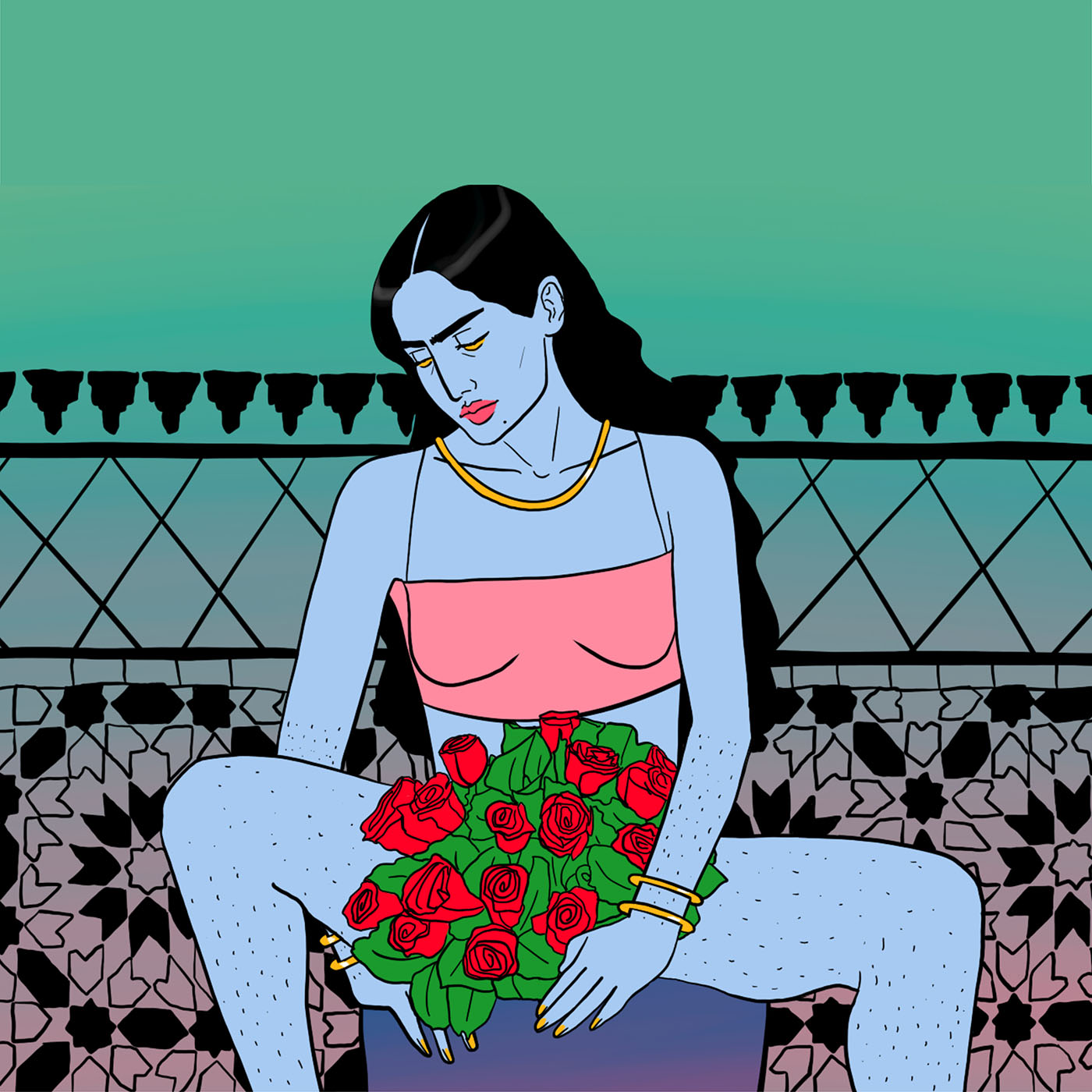

Notable artworks in the show are Zainab Fasiki’s bold and brightly-colored drawings, in poster-like clarity of line, which employ elements of kitsch and cartoon to confront patriarchy and denounce taboos around the female body — both in Fasiki’s native Morocco and beyond. With iron-filing-like leg hairs, veil-covered and naked women side by side, Fasiki’s works decry the profound inequalities characterizing male and female relations at a time when heritage and ancient history face the hyper-digitized and the modern. The culture of harassment, and the shame to which women are subjected are rendered in brilliant, striking colors, particularly those drawings of women of Muslim heritage who challenge stereotypical notions of beauty. Whether adorned with a black veil, a superhero’s suit, or presented nude, these figures exude strength and a range of emotion.

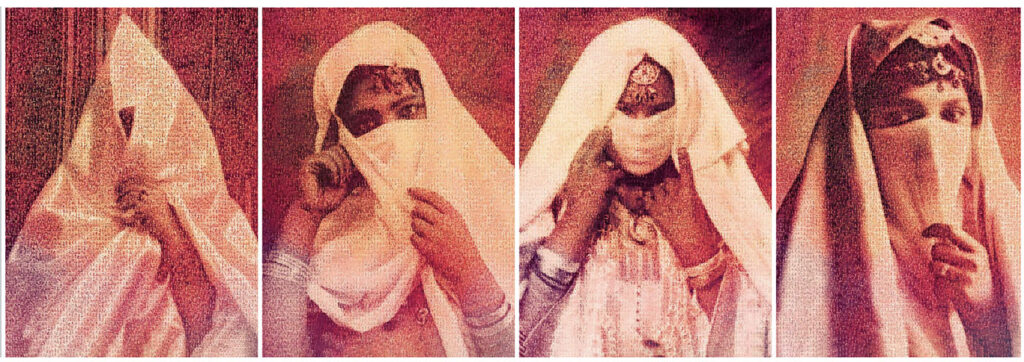

The largest work in the exhibition space is a prismatic portrait that on closer inspection reveals that it is made of squares on the main wall of the downstairs floor that reaches up past the second level of the gallery. Fatima Mazmouz’s “H.EROS, Portraits of Moorish Women” (2023) is composed with many repeating sides of erotic postcards from the early 20th century that were hand-written and sent home ostensibly to the West. Playing on the full Orientalist gaze, the series explores ambivalence between the American-European consideration of the exotic and the voyeurism around women of the SWANA regions, enacted by colonizing migrants and pillagers who wrote mundane notes home on postcards that exploited the women’s bodies. Reclaimed and transformed by Mazmouz, the images of colonial exotic postcards are shrunk and used as pixels, while the artist zooms in on the exoticized women’s faces that appear in further smaller works until they become figures of resistance, anonymous women once relegated to the status of objects of titillation and fantasy, now reclaimed as human yet gargantuan by the artist.

Curator Daria Khan explains, amongst all the difficulties putting on an exhibition like this, the biggest hurdle was in showing works about women’s resistance: “For this specific show it was funding, I reckon due to the title and political works that might seem provocative to some people. There is a social acceptance of feminism as far as it’s manageable, palatable and ‘safe,’ but not when it’s loud, gender-inclusive, political and non-compliant. Feminism is not conditional.”

Ambitious indeed, but also a series feeding into a larger overseas show is a sage method to build to a more extensive show that actually fulfills its remit, and that is to represent vastly different yet close sectors of every society. The US show will exhibit the chapters as a whole, with the same artists although the selected artworks will vary.

Presented with such grit, focus and pain during my time in the gallery space, I am reminded of Eyene’s reference to Langston Hughes’ “Our Spring” during her curator’s talk. An excerpt from the poem, written in 1933, appears below:

Bring us with our hands abound,

Our teeth knocked out,

Our heads broken,

Bring us shouting curses, or crying,

Or silent as tomorrow.

Bring us the electric chair,

Or the shooting wall,

Or the guillotine.

But you can’t kill all of us.

You can’t silence all of us.

You can’t stop all of us —

*The prefix “trans” implies “across, beyond, through, on the other side of”; while the “s” in “feminisms” recognizes the innumerable definitions of feminism worldwide.

*Nearly a yearlong series of exhibitions from spring until mid December 2024 at London’s Mimosa House, transfeminisms will be in five shows, called “chapters.” After that, the exhibition will travel to the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, Arizona, for 2025.

An interesting and important piece! This quote struck me: “Women make the world, they’re burned by it, they watch it burn and yet they remake it from embers. How do they continue while also resisting?”