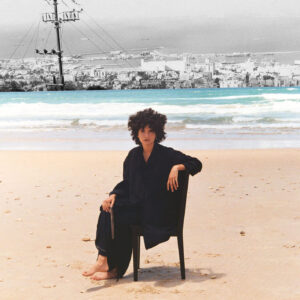

A writer born into both Arabic and Hebrew linguistic traditions finds herself writing in English but longing for Arabic.

My Arabic is mute choked at the throat cursing itself

without saying a word

asleep in the airless shelters of my soul hiding

from relatives

behind the shutters of Hebrew

—Almog Behar “My Arabic Is Mute”

There are certain words that always come to me in Yemeni. Words that appear on my tongue without effort. Words that come first, before my dominant languages get a say.

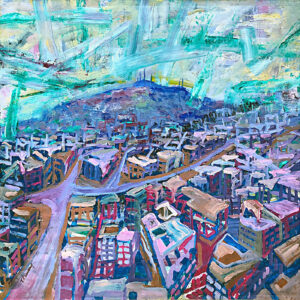

Yemeni Arabic, more specifically, the Judeo-Arabic vernacular of North Yemen, is the dialect my grandparents spoke their whole lives, and my mother and aunts still use when they sing, or when they pepper their Hebrew speech with Yemeni words or quote colorful idioms like “Your rib is broken when you marry off your son; you gain a rib when you marry off your daughter,” or imaginative curses such as “May the demons kidnap you.” The language I heard every time I visited my grandmother, watching her talk with her daughters, her friends, her words accompanied with expressive hand gestures and exaggerated sighs, sounding, always, either mad or cheeky. A language she used for endearments, infused with the love of ancestral mothers, Hayati, Ayuni, Galbi, my life, my eyes, my heart. A language I was surrounded by every time I walked the streets of Sha’ariya, the neighborhood in Israel where she lived, and where my parents grew up. A language I want to believe lies dormant in my body, genetically encoded into my cells, waiting to be awakened, activated. A language I don’t speak, and now it is too late. A dying language that, despite its disappearance from the world, managed to take root in my brain in the form of stubborn words that won’t let go.

The other day I slipped and twisted my ankle. Except, in my mind, I didn’t trip or stumble or ma’adti — the Hebrew word that should have come to mind. When someone in yoga class asked what happened, I eyed her. “Are you Yemeni?” I asked. “Half,” she replied, unsure. “Hitgal’abti,” I said, pronouncing the throaty ayin as it was meant to sound, as though a marble slides down your throat. Maybe the word stuck because of the mental image it invokes: the way the syllables trip out of my mouth and pile on top of each other. Whatever it is, other words simply won’t do.

Hanega, pronounced with a guttural het, is another one of these untranslatable Yemeni words. It comes to me whenever my eight-year-old daughter frowns, pouts, shrugs her shoulders, and refuses to talk. If my siblings or cousins are around, I’d mutter it to them knowingly, the way I’d seen my mother do with my aunts. When I’m with people who aren’t Yemeni, the word still rolls to the tip of my tongue before retreating.

I took to Facebook once to consult with other Israeli friends of Yemeni descent about the best way to translate hanega in my work. I was writing a scene for my memoir, in which I used the word to get a reaction from my grandmother. “Are you hanega?” I asked her. She turned to look at me, astonished and pleased to hear me speaking her language.

My post garnered 220 comments and almost as many opinions. “Hanega is not just being offended,” observed Ayala, a relative. “It’s an entire performance…the act of twisting your face and snubbing the offender. Hanega means she won’t easily be appeased. It’s more than a word or an emotion. It’s a cultural story.”

I delight in the sound of Yemeni rolling out of my mouth, rejoice in accentuating the letters in that deep, melodic way, feeling as though in my own small way I’m keeping something alive — an endangered language, yes — but also more personally, our past, my childhood, as though in using these words I am channeling my ancestors.

Maybe it also feels like an affirmation, because despite growing up in a Yemeni family, I have often felt not Yemeni enough, was accused of trying to be more Ashkenazi. Was it because I lived in Canada for so long? Was my light-brown skin not brown enough? Or maybe it’s because, like many other third- and second-generation Yemenis, I don’t pronounce the guttural het and ayins that Mizrahi Jews (Arab Jews who migrated from Arab lands) were once famous for. That accent, my parents’, is still imitated (poorly) and mocked on Israeli satire shows — often by Ashkenazi actors who play Mizrahi characters — even though it is the accurate pronunciation of Hebrew, which, like Arabic, was meant to have guttural letters. But the country was run by European Jews, so their (incorrect, mispronounced) way of speaking took over and became the norm.

Growing up I liked that I sounded like everyone else, that I fit in. Years later, as I began embracing my Yemeni identity, I regretted not learning this pronunciation from my parents, envied my cousins and friends who did. Now I admire the elegant and musical sound of it whenever I hear it. Sometimes I force it into existence. When reading my Hebrew writing in front of an audience, certain words no longer sound right if the het or ayin are not pronounced; flattening them turns them into different letters, and therefore the words are altered. He’almut, I might say with the glottal ayin. Disappearance. Or else, the ayin becomes an alef and the word might sound like Helamut: Muteness.

My grandmother never quite took to Hebrew. Arabic always came first, allowed her the range of wit and humor her adopted Hebrew never could. Like most women in Yemen, she was illiterate, but in her sixties, she took Hebrew lessons and learned to sign her name instead of dipping her thumb in ink as she had done before. After her death, I found an official document in my mom’s closet: my grandmother’s Hebrew given name (which she also never took to) scribbled hesitantly and childlike at the bottom of the page.

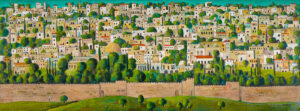

My grandfather, like other Jewish men, knew Hebrew from prayers, but that Hebrew was biblical, sacred, not for everyday use. When they arrived in Palestine in the 1930s, Hebrew, which had been a dead language for seventeen generations, became the only way these Jewish immigrants from different countries could communicate. How strange it must have felt to utter these words reserved for prayer in an everyday context, to shop in the market, to argue with a neighbor, to bring them down to earth.

My parents were born into this new language. My mother tells me my father never knew Yemeni, and even if he did, his family spoke the Sharabi dialect, from a different district in Yemen.

“Is it that different?”

“They pronounce g, and we pronounce j,” she said.

How could I expect to speak an ancestral language even my own father couldn’t retain?

Many years later, when I came to Canada and had to live in a new language — a language I studied in school but in which I scored a D+ on my matriculation exams, a language that felt unnatural and awkward in my mouth, its long and short syllables like a minefield designed to make me trip (Don’t say bitch when you mean beach, I prayed every time a visit to Kits Beach was mentioned) — I thought of my grandparents.

This is an essay about my longing for Arabic, but it is also an essay written in English, by someone who was born into Hebrew, who didn’t know English until she was ten, who hadn’t read an English book until she was twenty-four, who wrote her first story in English at thirty-three. There are days when I worry that writing in my second language is the most interesting thing about me as a writer. I understand the fascination. Writing in a second language, I had written once, is like wearing someone else’s skin, an act akin to religious conversion. This isn’t what this essay is about, but how can I ignore that part of my story? That facet of my writerly identity?

I write in English about people who speak Hebrew and Arabic, so it’s no surprise that words in these languages demand to be included; they migrate into the English text unitalicized and assert their place in the foreign settings, mirroring my own story of immigration.

After my family and I moved back to Israel in 2018, I got to watch my Canadian partner learning Hebrew, and my daughter, a true bilingual, weaving in and out of tongues, like a basketball player dribbling across the court. “Sometimes it’s tiring to live in two languages,” she said to me the other day. I sympathize. My eventual mastering of English came at the cost of my Hebrew. Language is a living, evolving thing, and I had been away for twenty years. I used to pride myself on my command of Hebrew grammar; now I am feeling challenged in both languages, a humbling experience that made me rethink my devotion to correct grammar and reconsider what really matters in a work of writing or in daily conversation.

These days, I find myself fearing for my English, again. Whenever my Hebrew flows, I worry my English is at risk. I’ve seen my mother tongue atrophy; no doubt it could happen to my adopted tongue.

The way we speak at home does not follow any of the recommended rules for raising bilingual children (where each parent must speak only one language). We speak Hinglish, or Ebrew, fluently switch, start a sentence in one language and end with another, and sometimes, mistakenly, we conjugate an English verb in Hebrew grammar. In a sense, the Judeo-Arabic spoken in my grandparents’ home was a similar creature. It was the same Arabic their neighbors in Yemen spoke but colored with Hebrew influences. Later, in Israel, Hebrew became more prominent, but the two were still interlaced, still interplaying.

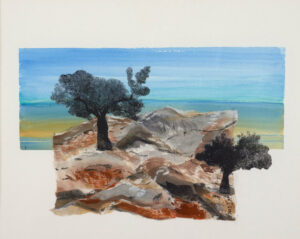

Moving back to Israel also meant moving to the Middle East, a part of the world largely ruled by Arabic. Palestinian Arabic is in the DNA of this place, and the neighboring dialects of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan surround us from every border. I grew up watching the weekly “Arabic Movie” every Friday with my mother, an Egyptian melodrama filled with heartbreak, betrayal, and forbidden love. Despite the different dialect, my mom didn’t need the Hebrew subtitles. When she went to the kitchen to stir the soup, she asked us to turn it up so she could listen in.

According to research by the Van Leer Institute in collaboration with Tel Aviv University, 10 per cent of Jews in Israel claim they speak Arabic, but only 1 per cent would be able to read a book. The percentage rises significantly, to over 25 per cent, among first-generation Arab Jews, but drops again with second and third generation.

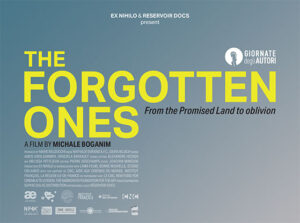

Mizrahi Jews, some of whom came later than Ashkenazi, faced prejudice and inequity in Israel. Their need to assimilate required an erasure of their past, a denial of their heritage and language, which wasn’t just foreign, or diasporic, but also associated with the enemy. Yiddish and other European languages were also lost, but Arabic was more politically charged. Despite sharing roots with Hebrew, which should have made it feel familial, it became viewed as dangerous, and hearing it instilled fear.

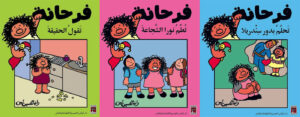

Children begged their immigrant parents to stop listening to legendary singer Oum Kolthum (once referred to by an ignorant Ashkenazi reviewer as a screamer), stop speaking Arabic in public. With the exception of the weekly Arabic movie — a source of comfort for many Mizrahim that was reduced to a cult phenomenon by Ashkenazim — Arabic language and culture were not celebrated in the public sphere. The radio didn’t play Arabic music, or Hebrew music that sounded Arabic, a genre they labelled Mizrahi music. The schools didn’t teach our history, our literature. A generation of children were raised to reject their heritage, their language, their parents.

The first time I heard Arabic spoken in Vancouver, instead of feeling nostalgic, I tensed up.

In 2018, Arabic was downgraded from an official language alongside Hebrew to a “special status language” — a move that caused outrage among Israel’s Palestinian population, but also many in the Jewish left, especially those with an Arabic background. In demoting Arabic, the Israeli government made a clear statement about the status of Arabic-speaking citizens in the country.

That’s how we ended up a Hebrew-speaking nation shipwrecked in the middle of the Arab world. This is how we ended up living among Palestinians, many of whom (particularly those with Israeli citizenship) speak Hebrew, yet we can’t communicate with them in their language. This is how we ended up knowing only the most basic Arabic words, mostly slang and swear words (words that turned Arabic from dangerous to obscene), words we claimed for ourselves, using them casually, carelessly, to the horror of our Arab neighbors.

“Language Barrier,” a web series produced by two fluent Arabic speakers, Eran Singer and Roy Ettinger, both Jewish and Ashkenazi, investigates what went wrong in Israel’s education system. They interview experts, visit schools, speak to Jews and Arabs. In one interview, Prof. Muhammad Amara from Beit Berl College says, “Language is not grammar…Language is dialogue. The biggest problem in Arabic language education in Israel is pinned in the fact that they teach it as an enemy language, not the language of the neighbor.”

I think of my poor Arabic teacher, a short, unsmiling woman with a thick Iraqi accent, her hair dyed an unnatural black, trying to instil in us an appreciation for her mother tongue. We weren’t excited about Arabic, not like we were about English learning. English was sexy. English was Hollywood. English was the future. For those of Mizrahi background, Arabic was the diasporic past we wanted nothing to do with; for everyone, it was a language of war. As homework we listened to Israel’s Arabic radio station, learning words like conflict, government, and negotiation. No wonder we lost interest. When the creators of the show enter an Arabic classroom in a Jewish high school, everyone in the room admits they hope to serve in intelligence in the mandatory army, proving Professor Amara’s point. In addition, they mainly teach Fusha, Modern Standard Arabic: good for reading but not for speaking. To illustrate this, the producer heads to the market and attempts to buy tomatoes while speaking proper Fusha. “I understood about 80 per cent,” the Palestinian shopkeeper replies.

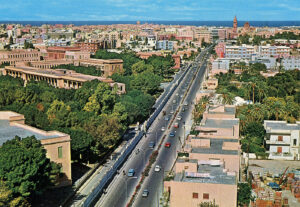

When I was 30 and living in Vancouver, I got a job waitressing at a Lebanese restaurant. Vancouver had almost no Israelis then, no presence of Hebrew. By then, five years into living in Canada, I no longer tensed to the sound of Arabic. At Mona’s I was surrounded by the language, the familiar cuisine, the music. At Mona’s my Middle Easternness was embraced and welcomed. I missed home, and Mona’s and the family who ran it gave me one.

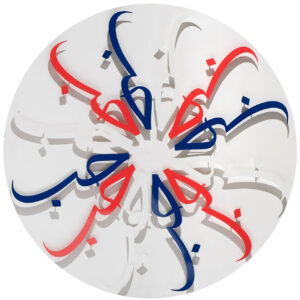

My first year at Mona’s, I hired Yusuf, an extremely well-dressed Iraqi man I had met there to help me with my Arabic. For some strange reason, I retained my knowledge of the Arabic alphabet, and often drew the rounded, cursive letters on paper when doodling. I recently found a note I had given my partner when we first met a few months after that. Beside my phone number I had written my name in English, Hebrew, and Arabic.

Yusuf was an experienced teacher, and he came to the yellow house I’d been sharing with four roommates off Commercial Drive with work sheets and handouts, complimenting me on my pronunciation and rapid improvement. But he was also way too flirty, and the day I told him so was the last lesson we had together.

I worked at Mona’s for six years. After some time, I started taking orders in Arabic, was able to explain poorly and haltingly to Saudi students how much a shish kabob platter cost and what would be on it. I started catching phrases in songs by Amr Diab and Nancy Ajram and was buoyed when I could sing entire lines. Being away from home and its prejudice toward the Arabic language allowed my body to remember Arabic, lament what was lost, and reclaim my own Arabness.

But even at Mona’s, surrounded mostly by Canadian Arabs, almost everyone spoke to me in English. My Arabic improved, but then I plateaued.

When I travelled back to Israel to visit, I began researching my Yemeni background, and for the first time used some of these words I’d always known when speaking with my grandmother. In my grandma’s last days, I began listening attentively instead of tuning her out. Thinking, here’s a word. I know that one. Here’s a saying. I have heard this one before. Her eyes beamed whenever I spoke Arabic. The gap between us abridged.

‘Learn Arabic,’ a Palestinian author I shared the stage with at a literary event in Tel Aviv pleaded with me. ‘If you moved back here, you owe it to yourself.’ What she was saying was, it wasn’t solely about my own past. It was about our shared future.

There are two Arabics I long for — my ancestral tongue and the language of this place — or is it really one? Arabic existed alongside my mother tongue for generations, a sister language whose words are often recognizable: bayit and beit, yeled and walad. They share many words, a similar ring, an etymological root, a lingual family, and yet they are estranged. If this is not a parable about the state of this region, I don’t know what is.

“Learn Arabic,” a Palestinian author I shared the stage with at a literary event in Tel Aviv pleaded with me. “If you moved back here, you owe it to yourself.” What she was saying was, it wasn’t solely about my own past. It was about our shared future.

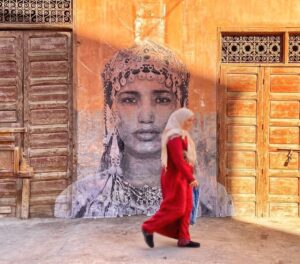

On a recent visit to Ushiot, a neighborhood in Rehovot steeped in the smells of fenugreek and cilantro, where recent immigrants from Yemen live, I heard a child speaking Judeo-Arabic Yemeni. He was maybe six, brown skinned, with side curls and a kippah. He almost looked like the photos I’d seen of Yemeni Jews taken decades ago. His mother was a young woman wearing a head scarf and born in Yemen, a rarity nowadays. The number of Jews in Yemen is in the dozens.

That child may be one of the last people to speak this language.

Who will he speak to when he grows up?

Some days I feel a physical ache for Arabic, a tug in my heart. How do you miss something you’ve never known? Can a language be lodged inside your body, folded into your organs, the same way we inherit memories from our ancestors, like trauma? How else can you explain the warmth that spreads inside my body when I hear it? The yearning?

I want this essay to have a happy ending. I want to tell you I signed up for Arabic lessons at the community center. Which I did, but then COVID shut it down before classes began. I want to tell you I enrolled my daughter in one of those few and rare Jewish Arab schools, where kids study in both languages. My partner and I went to visit one in Jaffa before she started first grade. Children ran around, playing in two languages, shifting back and forth seamlessly. “I’m sorry,” the principal said. “You must live in the district to enroll.”

What I will tell you is that I recently learned my memoir will be translated into Arabic, and how deliriously happy this made me; I’d been dreaming of being translated into Arabic. And then — how deeply sad, because I knew I couldn’t read it myself.

I may not speak Arabic, but these days I sing in Arabic.

When I discovered the Yemeni Women’s songs a few years ago — a repertoire of songs women sang at henna ceremonies, at births and weddings, a form of oral storytelling that had been passed on, unwritten, for generations, now on the verge of disappearance, of muteness — I wanted to learn them theoretically, through listening. Then I realized this wasn’t enough. I needed to join the singing, to become an active participant in the tradition of passing the songs on.

I see my teacher, Gila, at her home in a small moshav by Jerusalem. We sit in her living room, or on the balcony facing fields and hills. She teaches me the songs and their translation and tells me of their history and meaning. When I sing, my mouth does not stumble, even as it mimics words it doesn’t know. The translation is there, but when I sing, I rarely look at it. Singing is its own language. Before the pandemic, Gila even suggested I accompany her to sing at a henna. I don’t know if there’s anything more affirming than this.

The other day, as I was practicing the songs, my daughter inched forward until she stood next to me. Then her small voice joined in, imitating the foreign words. Her body knew what it was supposed to do too. As we sang, I tried to be still, to not disturb the moment. We sang and I could hear our ancestors singing along with us.

“Disappearance/Muteness” is excerpted from Tongues: On Longing and Belonging through Language (2021 Book*hug Press), edited by Leonarda Carranza, Eufemia Fantetti, and Ayelet Tsabari, and appears in TMR with permission from the publisher.

لقد تاثرت كثيرا بما ورد ولكون الكاتبة من اصول يمنية ِ.. رغم ان بعض الترجمات للعربية غير دقيقةِبالمجمل كان الموضوع (جنان ويزيغ العقل)لهجةيمنية

Pingback: La herencia judeo-yemenita rescatada por Ayelet Tsabari | JAD cultura judia

Pingback: La herencia judeo-yemenita rescatada por Ayelet Tsabari | Oriente Medio