The expectation that indigenous Moroccans in the Atlas Mountains would be able to answer questions in Arabic was the result of a diehard myth that everyone who lives in the land between Morocco and Iraq is Arab and speaks Arabic fluently. The truth, however, is that this expansive territory is full of indigenous communities that have their languages and cultures although they belong to larger nation-states.

Brahim El Guabli

Everyone feels pain. It happens within our bodies and minds, but we all cope with it differently. Its complexity is reflected in the absence of a scientific definition of pain — other than whatever the person in question considers painful. No one can or should define another person’s pain, because it would be an infringement on a human being’s fundamental right to choose the words that depict how their body or psyche experiences the hurt they feel. Every day, people articulate their pain, ranging from simple headaches to serious illnesses that require heavy duty medication. However, there are exceptional pains that take us aback and pose fundamental questions about not only pain but also about the appropriate mediums to convey it. The national catastrophe of the earthquake that struck Morocco is a moment to reflect on the disaster of language and the impossibility of relating Amazigh survivors’ suffering in a non-mother tongue.

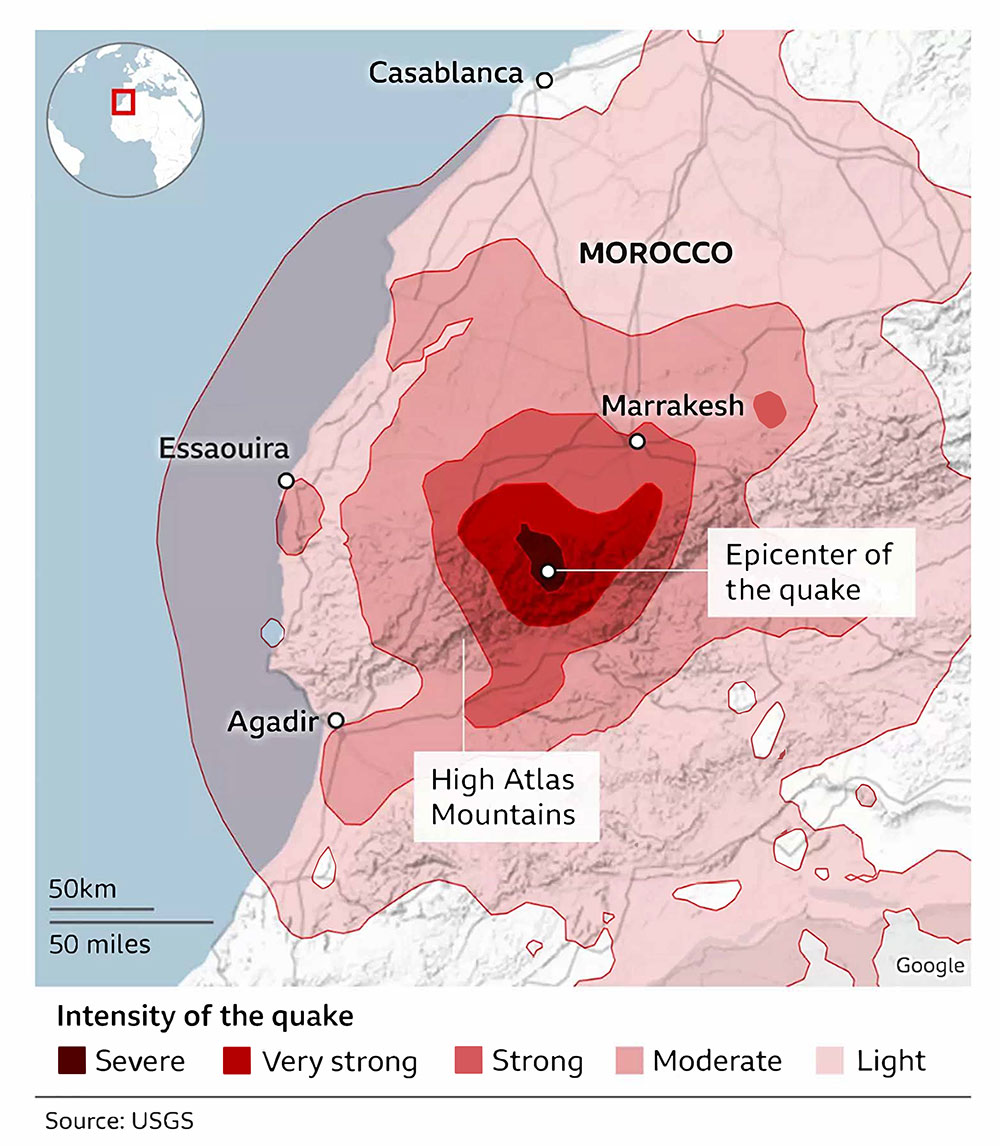

After Morocco’s devastating earthquake on September 8, 2023, both the world and many Moroccans discovered that the High Atlas Mountains are home to Amazigh-speaking populations. With its epicenter some 45 miles southwest of Marrakesh, the earthquake wreaked havoc throughout the High Atlas, killing nearly 3,000 people and wounding over 6,000 others, while demolishing fifty thousand homes and causing significant financial damage. As the world turned its attention to Morocco, Amazigh survivors of the earthquake shouldered the double burden of processing their trauma and conveying it in Arabic — a language thousands do not understand.

Apart from a few villages, the overwhelming majority of Moroccans in the Atlas Mountains speak Tamazight as a mother tongue. They live, exist, and breathe the air in Tamazight. They conduct their daily activities and worship God in Tamazight. They receive their phone calls and respond to them in Tamazight. They address the authorities in Tamazight, and celebrate their deaths and births in this language. The lullabies they sing to their children are in Tamazight, and the stories through which they encounter the world everyday are also in this millennial idiom. Their mother tongue is consubstantial to who they are as an integral component of the Moroccan nation.

Nonetheless, when the earthquake struck, they were called upon to diverge from this ordinary rule and use a non-mother tongue to share their losses. The various articulations of their pain in Arabic, which some media supposed is spoken universally in Morocco, is a case study for the way asking people to communicate their hurt in a language other than their mother tongue not only prevents an accurate and more fluid description of pain, but also becomes an obstacle that hinders audiences’ understanding of the immensity of the tragedy that struck central Morocco. The language we use to describe our pain is not peripheral to the relief and information effort; it is rather a foremost factor in the efficiency of any aid and recovery effort.

In her classic book, The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry argues that pain is both incomprehensible and inaccessible to others. Scarry writes that “[w]hatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unsharability, and it ensures this unsharability through its resistance to language.” Scarry pushes her analysis further, adding that “[p]hysical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it.”

Scarry was, of course, writing from an Anglophone tradition and at a time when Indigenous languages, like Tamazight, were almost inexistent in larger literary and intellectual conversations. However, Scarry’s provocative thought that pain both resists and destroys well-endowed languages is crucial for a generative reflection on how the articulation of pain works in a marginalized Indigenous language.

If pain eludes the powerful and terminologically-cutting-edge English language, then one needs to find out how Imazighen — the speakers of the Indigenous Amazigh language — have conveyed their pain after the catastrophic magnitude 6.8 temblor that decimated their villages and way of life in the High Atlas region. In the midst of the natural disaster in their homeland emerged the beleaguered language of Imazighen; it resurfaced like a phoenix from the folds of oblivion to shed light on multilayered historical narratives about North Africa and their limitations. The world finally saw that these Indigenous people of North Africa speak a language that is not necessarily comprehensible to Arabic speakers. Imazighen’s painful struggle to speak Darija (Moroccan Arabic) and Fuṣḥa (Modern Standard Arabic) is an entirely normal condition for those of us who grew up in villages and had parents and relatives who could not formulate a sentence in any variety of Arabic.

Despite Scarry’s argument that language breaks down in pain, it is still a crucial medium for the exteriorization of what one feels. Rather than focusing on whether Amazigh survivors’ pain is fully understood, it is equally fundamental to draw attention to a crucial, albeit basic, observation whether Imazighen were even able to voice their hurt after the earthquake.

The seismic catastrophe has elicited extensive media attention from both local and transnational press outlets. As I watched how Amazigh men and women were asked to respond to questions in Arabic without interpreters — a normal practice in Arabic-speaking media that host international speakers — it was obvious to me that their responses would have been better and richer if they were asked to respond in their mother tongue. This was an instantiation of both linguistic and traumatic erasure as people scrambled to find words and the right register to express their loss in a language most of them did not know well enough to engage in deep conversations.

In her book Translating Pain: Immigrant Suffering in Literature and Culture, literary scholar Madelaine Hron reveals how telling doctors that they had “pain everywhere” (malpartout, as it is pronounced by the first generation of immigrants) was the Maghrebi immigrants’ way of making up for lack of language skills, which impacted their ability to narrate pain. Instead of locating the source of whatever caused their physical or psychological ails, “malpartout” made the pain elusive and impossible to treat. Anyone watching the news must have noticed that the Amazigh individuals who were interviewed on Moroccan and international television in Arabic were unable to elaborate on their losses. They remained mostly limited to generalities, their sentences were very curt, and their narratives were unusually constricted. Where the same individual would provide ten sentences in their mother tongue, they only said four or five in Arabic interspersed with religious phrases and messages of gratitude they were used to hearing on television during moments of affliction.

Amazigh-speaking observers commented on the Moroccan television stations’ use of Darija to elicit information from their Amazigh co-citizens, who do not know the language. A critical message that argued that a national “media that does not speak Tamazight is a foreign media” was circulated on Facebook. The expectation that Imazighen of all ages would be able to answer questions in Arabic was the result of a diehard myth that everyone who lives in the land between Morocco and Iraq is Arab and speaks Arabic fluently. The truth, however, is that this expansive territory is full of indigenous communities that have their languages and cultures although they belong to larger nation-states — among them Kurds, Assyrians, Nubians, Armenians and others in southwest Asia, where an estimated 60 languages are spoken.

Communication in times of crises is not merely about media attention. It is fundamentally about sharing information with the world in order to mobilize empathy and elicit action in favor of the victims and survivors. Amazigh survivors of the earthquake in the impacted areas would have mobilized global sympathy better were they given a chance to address the word directly in their Amazigh intonation, using the Amazigh vocabulary for the disaster. As a result, the Amazigh pain was not conveyed in their own terms. The world would have heard “dunnit tmmussa” (the earth moved), “akal” (land), “iḍrḍ” (fell), and “immut” (died) as well as “arraw” (children/family), “tamghart” (woman), “issiwdagh” (scared us), and “tigmmi” (home), which all form a lexicon that Amazigh survivors of the earthquake use in their responses in Tamazight. The world would have also heard words, such as “agharas” (road), “aghanim” (bamboo), “akshshūḍ” (wood), “ikhla” (fell down), and “instm” (collapse); words that have specific significance in the language in times like these. Furthermore, Tamazight would have been heard globally after being relegated to oblivion for a long time.

Language in this situation is also an element of comfort and recovery. It allows the person who experiences loss to return to the world, to rediscover their topography, and name things that were and are no longer. However, another language cannot stand in for the mother tongue. As a consequence, the language barrier blurred Amazigh pain in some cases. The irony is that pictures and the materiality of the damage engendered by the earthquake communicated the tragedy in a more impactful way than the words of the survivors in their broken Arabic. The damage to the landscape helped audiences fathom the horrific experience the interviewees attempted to share in their curt responses to the media. The absence of translators who could mediate Amazigh words of pain directly allowed demolished houses and tons of debris that litter the villages throughout the Atlas to speak louder than the Imazighen themselves. Not that Imazighen cannot or could not speak, but it was because they were asked to speak in an idiom that is not theirs.

Of course, thousands of Amazigh children throughout Morocco learn Arabic and French in primary school and English or Spanish in high school. Even the educated youth sometimes do not know Darija until later when they move to cities to work or further their education. Apart from very few highly-educated individuals, the older generations remain mostly illiterate and their mastery of any other language beyond their mother tongue is very limited. Still, you can detect an Amazigh speaker through their accent and the deep influence Tamazight has on the way they speak. Language politics have not been brought up, and rightly so in a context of national crisis, as an element of analysis in the current catastrophe, but it is important to acknowledge that the disastrous unpreparedness of the main national channels to talk directly to people in Tamazight is reflective of the legacy of the 50-year marginalization of Amazigh language in post-independence Morocco. Amazigh World News has rightly underlined that the language barrier created by these channels “caused immense difficulties for survivors, who struggled to express their feelings and help needed.” A situation that also proves the obvious truth that language has far deeper ramifications than just cultural preservation. It impacts a people’s right to self-expression in times of crises, as we have seen.

This state of survivors was entirely different in videos recorded in Tamazight. In video upon video, Amazigh survivors of the earthquake effusively narrate their emotions, share their tragedy, and express their gratitude to all the help and assistance they received from their co-citizens. Both language and the image coalesce to make the videos recorded in Tamazight efficient in depicting the pain that people feel as a consequence of the earthquake. Those who speak Tamazight saw and heard and reacted emotionally to the flowing stories of Amazigh men and women. The cadence of their words was rhythmically quicker and richer in their mother tongue than it was in Arabic. Although not surprising, this speaks to the assurance and confidence that emanate from the comfort of speaking one’s mother tongue. Anyone who speaks another language other than their mother tongue knows that it takes a tremendous mental effort to render ideas and emotions correctly in good times let alone in times of tragedy.

This failure to convey pain in the mother tongue is not a new question. In reality, generations of Amazigh activists have drawn attention to the power dynamics and communication dilemmas that are entailed in the de facto demand that Imazighen use a non-mother tongue in their crucial daily affairs. The question has always been open about Imazighen of certain ages’ ability to conduct business, make transaction, seek health consultations, and engage in litigation in a language other than Tamazight. Particularly, both litigation and pain require storytelling, which has life-threatening complications. A failure to receive healthcare or a fair trial can end a person’s life both literally and symbolically. These Amazigh activists presciently demanded that Imazighen’s language be taught and rehabilitated. A long process of activism and negotiation has finally made it into an official language in 2011. Against Scarry’s theory that pain breaks language, I can posit that it is the absence of the mother tongue in the Indigenous context that breaks both pain and language. The non-mother tongue breaks, resists, and disables the ability of the Amazigh survivors to tell their story of survival and their apprehensions about what the future holds.

As this tragedy has shown, the question of communication with people in their mother tongue can sometimes leave the realm of culture and politics to become a question of life and death. The Morocco earthquake has revealed that one cannot provide rescue, furnish aid, and make sure that that there are no victims stranded in secluded areas without speaking the language of the survivors. This in and of itself is sufficient to remind everyone that up to now we have not really heard Amazigh pain in its own language. This disaster of language calls for a wider rehabilitation of Tamazight to be the center and the starting point of all pain; of all Amazigh indigenous suffering.

Moving forward, Morocco should step up its ongoing process to integrate Tamazight in education. Globally, Anglophone academia’s response to the earthquake has proven its need for Amazigh Studies experts who can shed light on Amazigh communities and their significance; a project that had seen better days in the 1960s through the 1990s but which the focus on the Middle East has terminated at the expense of Imazighen.