Al-Dujaili shows that nothing happens in isolation. Migrant detention in Trump’s U.S., Israel’s colonialism, and the climate crisis are all interconnected, reminding us that, despite borders, our humanity is shared.

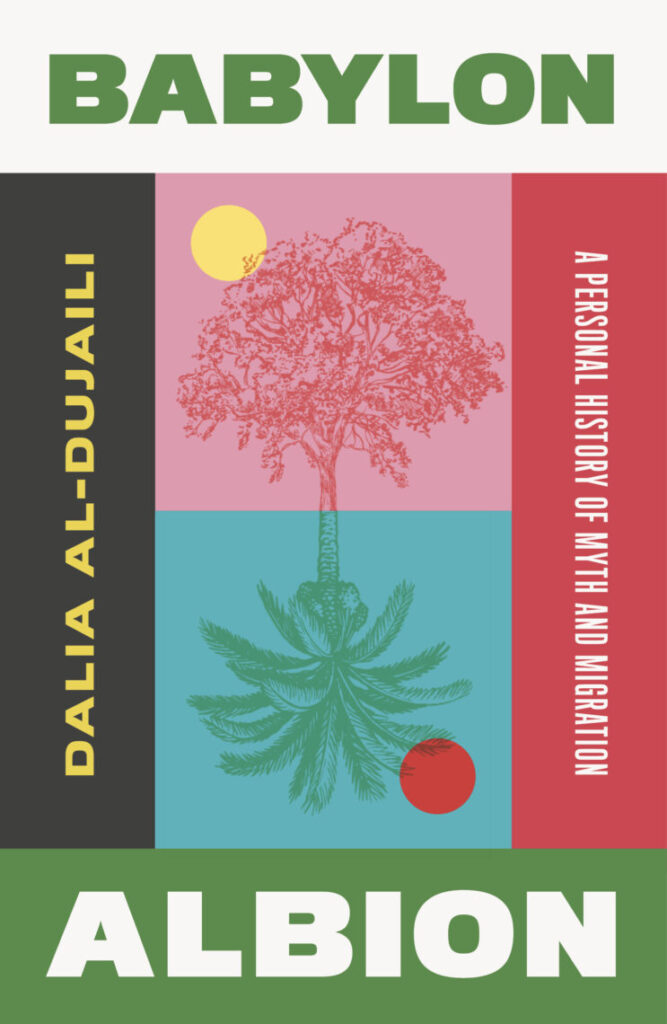

Babylon, Albion: a Personal History of Myth and Migration, by Dalia Al-Dujaili

Saqi Books 2025

ISBN 9781849250719

In today’s political climate, Dalia Al-Dujaili’s debut memoir offers a cathartic experience for fatigued bystanders. Her prose is a melodic blend of sentiments, meditations, frustrations, and reckoning, which draws on her Iraqi roots and British heritage. She intertwines her story with the earth, arguing that our ecological world is inextricably linked to our collective humanity and stories. Al-Dujaili writes:

I am unearthing the stories we carry in our bones, in our blood, that maintain us through the constant transience of home. We must dig up the soil inside us to discover whose memories are buried there.

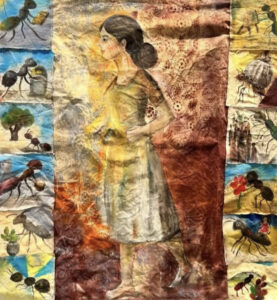

Alongside her memories, Al-Dujaili draws from folkloric myths and religions, and proposes scientific evidence to compose the four chapters of this lyrical narrative: Forests of memory, Holy Water, Paradise of Earth, and Common Ground. The premise of the book ruminates on the existential questions of what it means to belong and to be a native, what makes a place or country a home, and what the world would be like without the arbitrary and artificial borders drawn by colonial enterprises that lay claim to the globe.

Al-Dujaili, who was born in the UK, weaves together vignettes from her childhood spent in the British suburbs. In her reflections, she discovers a connection with the English oak, viewing it as a witness to history and a reliable truth-teller. The tree holds a significant place in national identity and biblical narratives, much like the date palm does in the hearts and minds of the Iraqi people. With reservations, she candidly admits to feeling more at home amongst the wet soil of Britain than Baghdad’s arid land. Yet, despite this untethered feeling, the land she comes from is embedded in her blood.

The oak and the palm used to confront me with my apparent inconsolable duality. Now, they show me both the deep symmetry between British and Iraqi history and heritage and the beauty in the differences between the two.

Furthermore, the plants, trees, animals and micro-organisms that make up the fabric of our world are shared resources, belonging to all of us. As the author emphasizes with her personal wisdom and evidence-backed data, history shows that we have always been a migratory people, moving from place to place, scattering and nurturing the seeds of our lands and cultures along the way.

A culture too, is an extended act of pollination — people who are on the move collect stories and drop them along their path like seeds, which then not only root themselves in that new land but pick up cues from the environment into which they grow, germinating further and influencing the ecosystem where they have been introduced, reproducing and even mixing with other life to create entirely new and unique life, new stories.

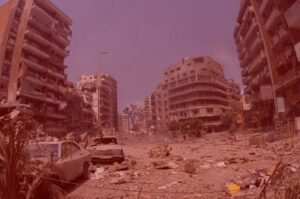

Babylon, Albion was published under the shadow of interminable global strife and chaos. In Gaza, during the genocide, Israeli shelling has wrought not only violence on Palestinian people, but on the land as well. The ongoing occupation is a present-day example of the eco-colonial warfare that Al-Dujaili highlights in her book. The term “ecocide” first gained prominence when the U.S. used chemical weapons in Vietnam during the war there. Now, we see ecocide being enacted in real time against Gaza’s once lush strawberry fields, lemon trees, and olive groves, which have been completely decimated by an estimated 80,000 tons of bombs, many manufactured in the U.S. and Europe, which have been dropped since October 7th. As a result, Gaza’s soil contains radioactive and carcinogenic elements, such as depleted uranium and phosphates, and all its drinking water has been deemed unsafe for human consumption. Two-thirds of northern Gaza’s land was once agricultural, and now, it is all rubble, not to mention that there have been reports of Israeli planes dropping herbicides over border agricultural areas in recent years.

The second chapter of this unusual memoir is, essentially, an impassioned ode to how nature, specifically water, sustains human life. Although it begins with her early memories of swimming lessons in Surrey and the dulcet sounds of evenings by the sea at Brighton beach with her mother, Al-Dujaili segues into nostalgic scenes of a storm over Baghdad. Against an invocation to the nourishment of water, how Earth is mostly made of this resource and its life-giving properties, she converges the two halves of herself, stating that “the Euphrates and the Tigris and the Nile converge to meet the pebbles of Brighton Beach…”

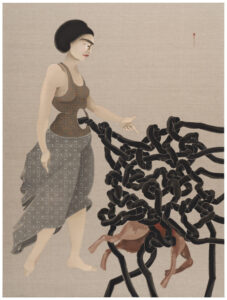

Scenes of her childhood summers “swilling at the waters of Worth Bay” soon take us to the marshes of Iraq, described in Al-Dujaili’s narrative as a cornucopia of spirits and stories. She re-highlights the experiences of the Marsh Arabs, whose livelihood depended on buffalo herding, fishing, rice growing, and reed harvesting — before their lives were upended by severe droughts caused by climate change and the pressures from both foreign colonial and domestic capitalist interests. Additionally, Saddam Hussein drained the Iraqi marshes to flush out the Shi’i rebels, resulting in the destruction and displacement of the communities that depended on these wetlands.

A succession of wars, invasions, civil conflict, and centuries of colonization have resulted in destitution for many. Drought and degradation of water sources have caused unprecedented health ramifications, for many more. The forces responsible for Gaza’s ecocide are cut from the same cloth as those responsible for Iraq’s unwilding. Both situations reflect a pattern of exploitation and neglect, where human actions contribute to severe environmental harm and loss of biodiversity. These destructive practices illustrate a broader systemic issue affecting vulnerable regions.

In Babylon, Albion, Al-Dujaili intertwines her intimate experiences with grounded research, thoughtful reflection, and myths written with astute care and fluidity. While crafting atmospheric scenes of eating Iraqi masgouf in Amman with her family, she finds a way to keep Iraq alive inside of her and consistently reiterates that the personal is political. In sharing this story, she reminds us that eating the masgouf fish on the bank of the Tigris is a shared memory of émigré Iraqis, and this tradition is now under threat due to the river’s levels of toxicity and pollution. Her story of diaspora and longing is part of something far more seminal in the ongoing history of humankind and the planet itself. Back in London, her kinship with her beloved oak tree cannot stop her from contemplating the violent legacy of the British Empire — a legacy of pillaging and conquest, and its everlasting consequences. The healing and spiritual aspects of nature are inaccessible to many, as she notes how Black and Asian children in the U.K. statistically have less access to green spaces. Similarly, the beloved English rose originated from Southwest Asia and is the national flower of Iraq, where it is a true native.

Much like the English rose is foreign to the English land, the lion that has come to represent England can trace its beginnings back to Mesopotamian folklore. Al-Dujaili wonders if Britain’s selective memory attempts to portray a past that is exclusive of migration. Across the globe, this idea of the alien and foreign migrant has permeated society. In the U.K., Nigel Farage’s Reform party, like Donald Trump’s inhumane ICE raids in the U.S., human beings are reduced to invasive intruders.

Never mind that, by nature, we are migratory creatures, or that the boundaries which delineate our countries today pay no heed to our borderless oceans that are inviting to everyone. Those in power imposed these borders for their benefit. In turn, it has resulted in a severe moral rupture and a scorched earth. The consequences of these policies and vitriol are resounding, and Al-Dujaili does not mince words when telling her story. She writes that many of the rural sites across Britain are military training grounds and manufacturing factories for weapons that plunder the Middle East. Not to mention that when empires swoop in to draw borders on states like Iraq, they do so with limited knowledge of these lands.

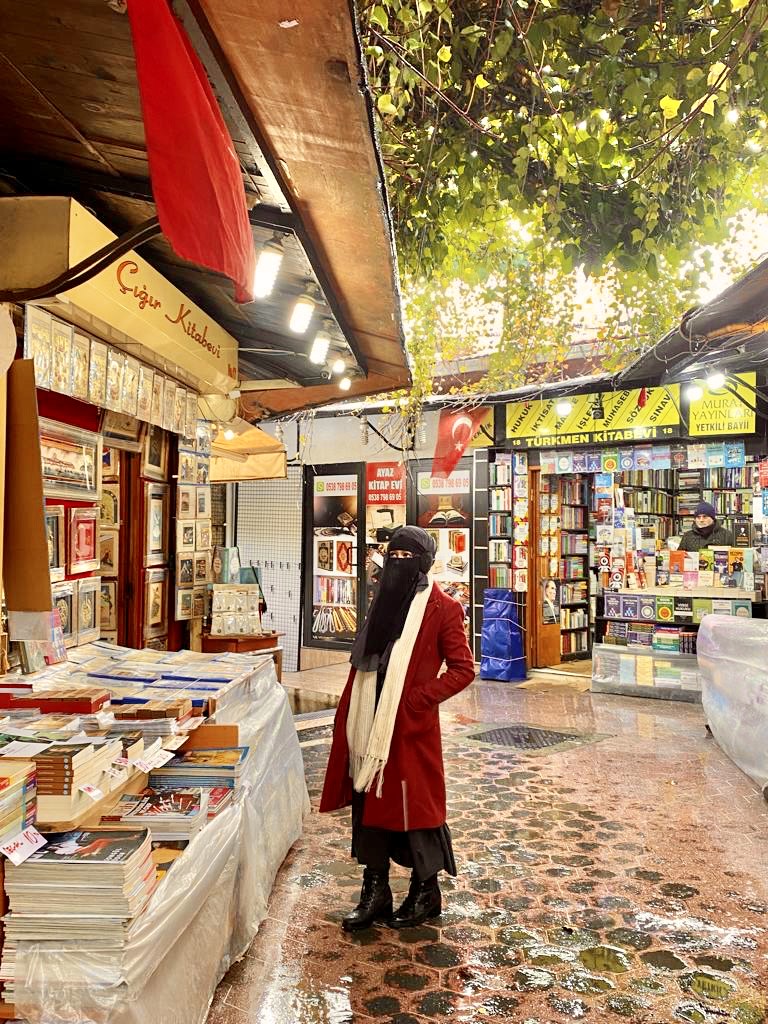

According to her Saqi bio, Dalia Al-Dujaili is an Iraqi-British writer, editor, and producer based in London, where she edits the online British Journal of Photography; her work has appeared in The Guardian, Dazed, GQ, WePresent, Aperture, Atmos, It’s Nice That, Elephant Art and more. She is the founder of The Road to Nowhere Magazine and in 2023 she was the producer of Refugee Week.

Al-Dujaili’s words and reflections are a deluge of knowledge and revelations. It is an exposé on the state of global society. How corporate and capitalist greed have shattered our relationships with the planet and our ancestral lands, highlighting a chronicle of violent moral failings. A few weeks ago, the world watched as one of the most famous climate activists of our time, Greta Thunberg, undertook a perilous journey to deliver aid to Gaza, challenging the avaricious sanctions. She made it clear she would not divorce her passion for environmental justice from social justice, citing a clear link between ecological devastation and political violence. Studies have revealed that the war itself is exacerbating climate change, which suggests that we cannot claim to care about the environment without fighting against the suffering of all marginalized people.

Al-Dujaili’s family was uprooted from their ancestral homelands due to the very same entities Thunberg is battling. Her mother planted a date palm tree in their backyard and, against all odds, nurtured it to life in the dampness of Britain. Although, like many before and after them, they were forced to make a foreign land their home, they did find a sense of belonging.

We all have a spiritual connection to our homelands, and violent displacement cannot sever it. Moreover, civilizations, trees, and entire ecosystems would not have flourished without migration. The forced sedentary lifestyle imposed on us is an unnatural phenomenon. This notion of calling human beings “aliens” and illegal to a land, without acknowledging the terror that has exiled them, fails all of humanity.

Al-Dujaili shows us that nothing in this world is an isolated event. From the forced detention of migrants in Trump’s United States, to the colonial enterprises of Israel, to the climate crisis, all are interlaced in the same way that, despite borders and nationalities, we share our collective humanity. With inherent idiosyncrasies, the convergence of Babylon and Albion is a light to a more compassionate future. As Al-Dujaili gracefully concludes in her afterword, “When we reconnect with our past, we have no beginning or end, borders or hard edges, because we belong to a celestial cycle greater than ourselves.”

An earlier version of this review mistakenly stated that Al-Dujaili was born in Iraq.