<

<

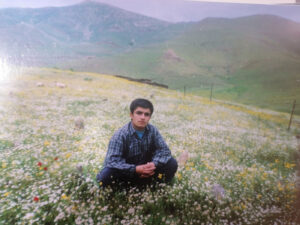

Iraqi writer and filmmaker Hassan Blasim has found refuge in Finland—”the happiest country in the world.”

God 99, a novel by Hassan Blasim, trans. Jonathan Wright

Comma Press Nov. 2020

ISBN 9781905583775

Chess-playing people-traffickers, suicidal photographers, absurdist sound sculptors, cat-loving rebel sympathisers, murderous storytellers… The characters in Hassan Blasim’s debut novel are not the inventions of a wild imagination, but real-life refugees and people whose lives have been devastated by war. Interviewed by Hassan Owl, they become the subjects of an online art project, a blog that blurs the boundaries between fiction and autobiography, reportage and the novel.

Winner of an English PEN Translates Award, God 99 reveals Hassan Owl as an Iraqi refugee struggling to establish himself as a writer, both in his newly adopted Finland and back home. On receiving a grant to develop a website for his otherwise unpublished work, he instead decides to embark on a series of interviews that will capture the real stories behind Europe’s so called “refugee crisis”. This book is the highly anticipated debut novel by acclaimed Iraqi writer, poet and filmmaker Hassan Blasim, blending the fantastic with the everyday to explore themes of exile, humanity, art and philosophy.

My Uncle BBC

an excerpt from God 99

By Hassan Blasim

I thought about starting the God 99 blog after I became anxious about not being able to write. I wasn’t anxious that I might lose money or my reputation. How could I be? I’m an unknown writer living as a refugee in Finland and no Arab publishing house has ever wanted to publish my short stories or my poems. They say my Arabic is vulgar, lacks beauty and offends religious taboos. Much has been said about literature and how people are attached to writing in general. Pessoa said something to the effect that literature was the most enjoyable way to ignore life. In my case, literature hasn’t only provided ‘hiding places for pleasure’, but I would also argue that literature has saved my life, since I was born in a country where every decade the barbaric level of violence has risen to higher and more grotesque levels.

God 99 by Hassan Blasim is new from Comma Press.

Your official profession in that country was a vet. You used to treat cows in the villages around the city of Babylon. The last time you smelled a cow was twelve years ago. You wrote a funny story called “The Cow Whose Cunt Turns Out Porno Mags”.

In my adolescent years, I read the expression “Ideas are thrown on the roadway,” and it excited and enthused me, particularly when I replaced the word ideas with the word stories. As time passed, what at that age was my dream of a profusion of stories turned into a nightmare. The avalanche of images, information, news and stories now horrifies and disgusts me. It makes me feel I’m powerless and that writing is futile. I wrote to my dear friend complaining of my despair. In the email she sent in response, she said, “Despair associated with writing is definitely a complex form of despair. It includes despair brought on by the absurdity of the world as well as despair brought on by complete paralysis towards it – not the partial paralysis that has afflicted writers in certain markets. The cause of this latter type of writerly despair is the thought that what we write doesn’t read like a cry in the wilderness, but more like a fart in the wilderness. That’s how the world is constructed and I’m convinced it’s not my fault that it’s so frivolous. Let’s write, my dear, according to Henry Miller’s formula (I learned from him that I shouldn’t do anything else but write, that I must write and write and write). I understand your situation, but the idea of stepping back must be dismissed. The only thing stopping us from falling into the pit of despair is defiance and perseverance. For sure, what Miller said is no more than a bunch of advice, but what’s to be done if the advice remains valid and useful in so many contexts!”

Your friend’s emails give you joy, pleasure and consolation! You want to meet her face to face, hug her and smell her.

I was watching a report about the discovery of a new mass grave in Iraq when I had the idea of starting a blog and publishing my short stories and poems as a way of circumventing Arab censorship. I went online and searched for free blogs. It quickly bored me. It was ten o’clock at night, so I got changed and went out to a bar. I thought my blog should have a uniform writing style and that all the texts should be new. I drank beer and Jaloviina as I rummaged around in my memory and mulled over the idea of the God blog. I met a nice young Senegalese man and we got drunk together and laughed a lot until the bar closed. He told me about his childhood in Senegal and I told him some amusing anecdotes from when I was working as a vet in the Iraqi countryside. The next morning I woke up and the remains of a dream about my uncle were still stuck in my mind. I sat on the edge of the bed and opened the laptop. I thought the beginning should be simple and distinctive i.e. collecting writing material through interviews with people in the real world. Later I thought about the shape of the mould into which I would cast the material. As I had breakfast I gathered together the fragments of my dream about my uncle and went through the pages of my memories of him. I put some music on. At first I listened to Massive Attack, then switched to Radiohead before settling on Nils Frahm. After drifting off, it suddenly occurred to me that the God blog could have roughly the same rhythm as my uncle’s garbled stories.

I was born into a poor family. I heard the story of my birth from my uncle dozens of times. He would tell the story and joke about it on every family occasion, until I hated the story of my rubbish birth. My uncle said I was born in the city centre hospital. At the time my father was at the front killing Iranians. My mother didn’t have enough money to take a taxi home, so she called my uncle to ask for help. My uncle arrived at the hospital in a municipal rubbish truck. One of the nurses brought an empty egg box from the hospital kitchen. They put me in the box and we went home in the rubbish truck. The truck was orange and on the side it said “Keep Your City Clean”.

Your uncle suddenly abandoned his family and moved to Cairo. At the time you felt it was now your turn to take revenge on him in the same way – by telling his story on every family occasion, whether sad or joyful.

Throughout his youth my uncle had worked as a government driver with the municipality. He drove a Land Rover for oil engineers and a Toyota truck for the staff in the agriculture department, and then he drove for the deputy governor. Eventually he was promoted to the highest position municipality drivers could dream of, as driver to the governor himself. He was a skilful driver who kept his cool and knew how to keep secrets. He had only one problem: he drank far too much tea. He drank it all day long. They say he would wake up in the middle of the night, have a cup of tea and three cigarettes, and then go back to sleep.

One day my uncle the Tea King drove the governor to a part of town where rich people lived. The governor was visiting a brothel. My uncle waited outside the house for more than an hour and he urgently needed a dose of tea, but there wasn’t a single tea place in the neighborhood. He decided to drive the governor’s car to the nearest coffee shop, have a cup of his sacred tea and then rush back. The governor came out of the brothel ecstatic but couldn’t find his car. While my uncle had been driving back from his cup of tea, he had collided with a truck carrying watermelons. The front of the governor’s car was smashed in, my uncle’s skull was fractured and the watermelons spilt onto the roadway. The governor punished him by assigning him to drive a rubbish truck for a whole year, and after that he was dismissed from government service.

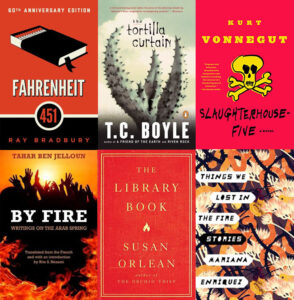

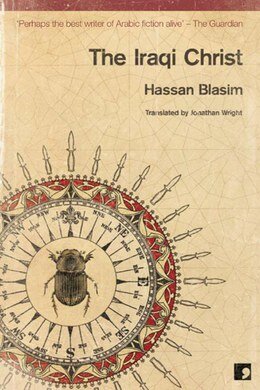

The Iraqi Christ, stories by Hassan Blasim. From legends of the desert to horrors of the forest, Blasim’s stories blend the fantastic with the everyday, the surreal with the all-too-real. Taking his cues from Kafka, his prose shines a dazzling light into the dark absurdities of Iraq’s recent past and the torments of its countless refugees. Order here.

Now my uncle was out of work. He spent most of his time either at home or in the local coffee shop where men played dominoes. The coffee shop was packed with unemployed men, foolishly smoking away their lives as they lined up their dominoes cheerfully and enthusiastically. At home all my uncle could do was drink tea, smoke and listen to BBC radio. The government jammed the BBC wavelengths, which made it hard to hear the BBC Arabic news reports clearly. My uncle took the distorted stories from the radio, went to the domino men in the coffee shop and told them the stories in his own way. He was very good at bringing the garbled stories he heard back to life. His wife, my aunt, struggled to feed their five children by sewing clothes for poor people. My uncle was out of touch with the real world of his wife, who was an attractive woman though her beauty had been worn away by the cruelties and bitterness of time. My uncle ended up like a statue in the form of a man sitting by the radio drinking tea. He didn’t speak to his family or listen to their concerns. His senses interacted only with the distorted stories on the radio and the domino tiles in the coffee shop.

After the fall of the dictator, the BBC and most international media came into the country, and my uncle lost his role as storyteller in the coffee shop. The country was so full of news, pictures, analyses and celebrities that people could no longer tell what was real and what was imaginary. The stories were distorted again, but in a different way. This time the truth was drowned out in a deluge of news and images.

The first obstacle you faced was financing the God 99 project.

I needed to travel to several countries to meet the people I wanted to interview – people I had read about in the media or that I had already met myself or that other people had told me about. I’d previously made an unsuccessful attempt to get a grant to write from the cultural authorities here in Finland. They were right! Who would be interested in stories by a refugee cow doctor who writes in Arabic? On top of that, this time I was asking for money for a blog project, and I didn’t know if anyone would be interested in such nonsense. I didn’t have any other option. I submitted grant applications to several organizations and waited. While I was waiting I worked on gathering information about the people I planned to interview. I obtained agreements in principle and set a timetable. I almost abandoned the project several times, but encouragement from my dear friend enabled me to persevere until disaster struck and vast numbers of refugees flooded into Europe, bringing about a small miracle for me. The doors of finance opened up here in Finland, because the migrants or refugees might have voices, faces, and stories to tell. I received a reasonable grant because of the humanitarian disaster and I set out in search of the names of God.

Soon you’ll finish the first tranche of the interviews, but you still haven’t published any of them.

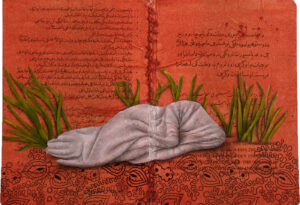

The people I have interviewed have been through a wide range of experiences, but what all the protagonists in this blog have in common is that most of them have had their lives disrupted in one way or another. I’m not sure whether I intend to publish the interviews as they are, without rewriting them in a novel or short story format. I’m still undecided. Most of the interviewees in this first stage are people who are immersed in their own worlds, with a variety of goals and philosophies. In their stories I was definitely looking for some of my concerns as an artist and as a vet. Or maybe, timidly and hesitantly, as I rummaged through other people’s lives, I was looking for the kind of “strong killer stories” that my childhood friend Habib was looking for. Habib is an open wound in my side. He gave me cruel, frightening evidence that our lives are just a game with unpredictable rules, following unknowable paths. I intend to devote the second set of interviews to issues related to bodies. Finally, I’ll interview people I haven’t heard of and don’t know, people who live in countries I’ve never been to.

You haven’t been able to meet some of the interviewees because death snatched them away before you reached them.

Yes, unfortunately, but I haven’t given up the idea of interviewing them. I believe that the dead still have the right to make jokes and tell stories!

It was a character accused of terrorism who inspired the title of the blog, and you’re planning to confine yourself to 99 interviews for the God blog.

It’s still a long way before I reach the 99th interview. I don’t have much of the grant money left. I only have enough left to cover one more trip out of Finland. I’ve made up my mind: I’ve decided to spend it on a ticket to Cairo to look for my uncle.

God 99 is published by Comma Press (UK) and is out now, available to order here.