Lamia Joreige’s “Uncertain Times” is on view at Marfa’ gallery in Beirut through Feb. 9, 2023, Tuesday to Friday, 12 – 7 pm and by appointment. This review includes excerpts of Amaya-Akkermans’s interview with the artist. (See end of article for upcoming dates with Lamia Joreige.)

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

“Nobody knows what really happened” is the conclusion that Lebanese visual artist and filmmaker Lamia Joreige reached upon investigating the story of the death of her great-grandfather, Ass’ad Daou, in 1916, a year after a massive locust invasion devastated Mount Lebanon and contributed to the great famine that resulted in over 200,000 deaths. The circumstances of the time, in the middle of World War I, couldn’t have been more dramatic: the Allied Powers blockaded the Eastern Mediterranean in order to circumscribe the Ottoman Empire’s military maneuverability, and Djemal Pasha, commander of the Ottoman Fourth Army, deliberately barred much-needed crops from Syria from entering Lebanon.

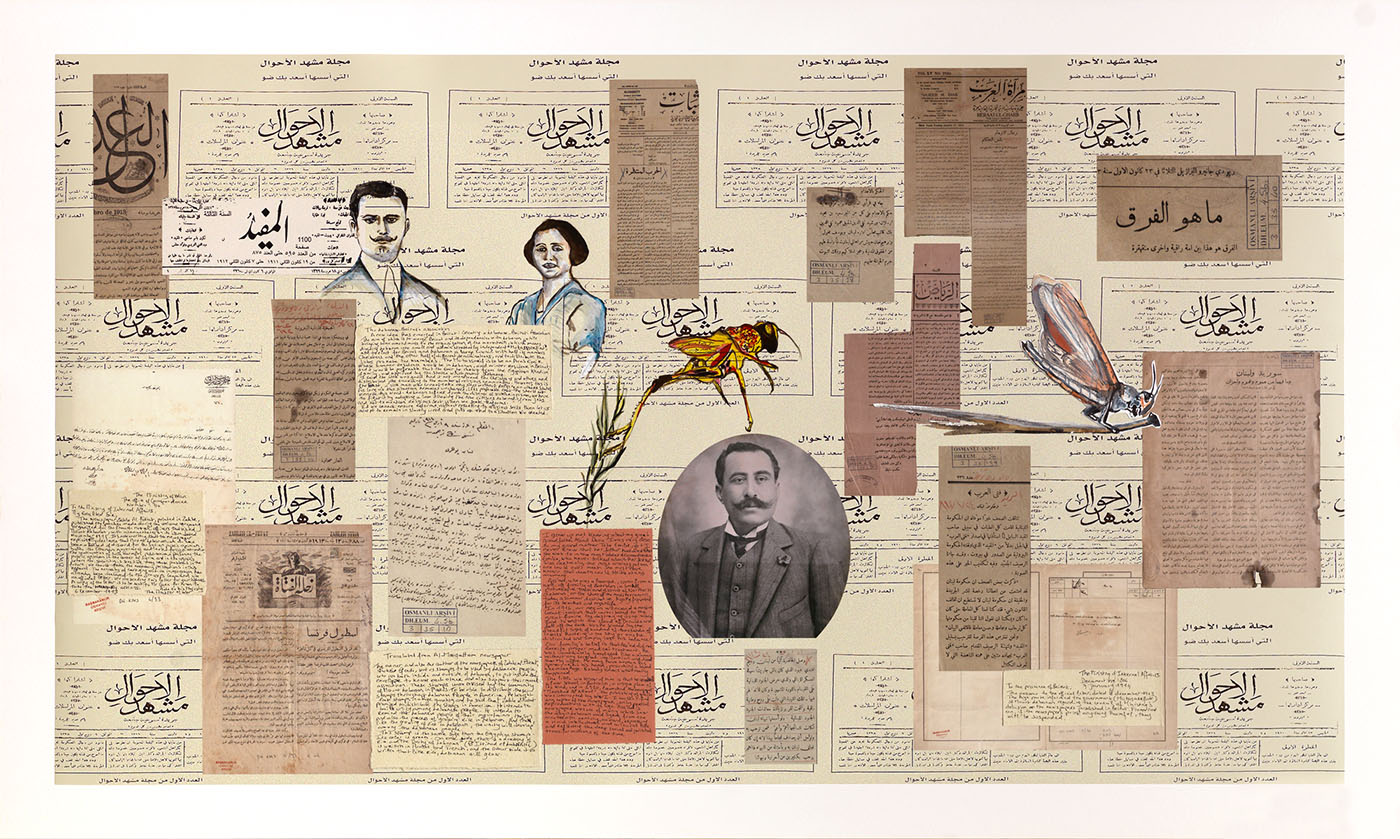

Daou, who had established a law school in Batroun, modern-day Lebanon, and, in 1910, launched the newspaper Mashhad Al Ahwal, died in the most absurd circumstances. Joreige recounts:

Ass’ad climbed on a rock overlooking the land to watch the cloud of locusts and fell off the rock. Was he scared by the dreadful sight of hundreds of thousands of insects hovering the sky, or was he distracted and simply lost his balance? Our family belief is that Ass’ad did not receive proper medical treatment; he was immediately bandaged without any surgical intervention and died shortly after. He may have broken his spine, or hit his head provoking a blood hemorrhage.

This personal recollection was written by the artist for the visual montage “The Deadly Fall of My Grandfather,” part of the series “Uncertain Times” (2022), a heterogeneous body of work covering the period between 1913, which was the eve of the first World War, and 1920, when the French and English mandates for Syria/Lebanon and Palestine, respectively, were created following the war. “Uncertain Times” assembles drawings and texts by Joreige and presents them alongside selected archival documents and photographs from the World War I period in Lebanon and Palestine. Through these documents, drawn mostly from the Ottoman Imperial Archive in Istanbul, Turkey (but also from other sources), the viewer of the installation is exposed to fragments from a bygone world: censorship of the press, sectarianism, treason, executions, and protests.

But is it really a bygone world? There’s an underlying tension between the archive and the personal narrative, insofar as their respective orientations in time are concerned: Joreige speaks from the present towards the past and then returns to the present, whereas the archival document remains firmly fixed to the past, and cannot move in any other direction. The meeting, in the past, of the archive and the personal narrative is always the result of sheer chance.

Joreige’s montage is a composite image, but it is also a document and a personal recollection. The artist’s writing becomes an image among images, but not in the sense of a photograph or a painting — there’s no whole. It is a multitude of appearances and fragments. A year ago, Joreige wrote of what had motivated her to create “Uncertain Times” in an essay for Perambulation : “I wish to express the tensions and anxieties, but also the expectations felt by the population of that time. What were their hopes for the future? How did they survive? How would political issues be reflected in their daily lives? What were then the promises of democracy?”

In conversation with The Markaz Review, Joreige explained that, additionally, the recent (and ongoing) feeling of anxiety and uncertainty in the region helped to trigger her interest in looking back at a moment pregnant with profound historical transformation, rupture, fragmentation, and creation:

The project began when I started feeling that the uprising in Syria — something that was completely mind-blowing to us, had turned into a full-blown war and Syria became fragmented, just like Iraq. At the time I thought that it could reach Lebanon and the country could be itself redesigned and transformed in ways that were similar to the period between the world wars. Syria had been completely fragmented and we were living in total uncertainty. Conspiracy theories about the future of the region were as widespread as they had been throughout the 20th century.

The second iteration of “Uncertain Times” is now on view in Beirut at Marfa’. The exhibition consists of a long series of mixed media montages bringing together drawings, archival photographs, documents, and personal commentary, thereby creating a correspondence-of-sorts between text and image. Joreige is not merely connecting the past to the present, but probing what these events might mean for us here and now, knowing what we know today.

In the multimedia installation “Mapping a Transformation” (2022), the first iteration of “Uncertain Times,” which was recently on view at the 17th Istanbul Biennial (Sept. 17-Nov. 11, 2022), Joreige focused on the migratory movement of Ottoman subjects fleeing military conscription and seeking opportunities elsewhere, the Ottoman First World War-era monopolization of crops that led to famine in Mount Lebanon, and Arab nationalist movements against Ottoman rule in the period 1913-1921. A variety of perspectives from Arabs, Turks, Armenians, and Europeans expressed the tensions and anxieties felt by people at the time, through books, articles, documents, and personal accounts.

Among these personal accounts, there are extracts from the diary of Ihsan Turjman, a Palestinian soldier in his early 20s, who was enrolled in the Ottoman army during World War I. This account reappears at the exhibition in Beirut in the montage titled “The Diary of a Young Ottoman Soldier” (2022). In his diary, Turjman writes passionately about a woman whom he hopes to marry, but also lays bare his more immediate concerns about fighting on behalf of the Ottomans: “I cannot imagine myself fighting in the desert front. And why should I go? To fight for my country? I am Ottoman by name only, for my country is the whole of humanity.”

He interrogates his tentative place in the Turkish-dominated Ottoman Empire as a Palestinian Arab: “But what have we actually seen from these promises? Had they treated us as equals, I would not hesitate to give my blood and my life — but as things stand, I hold a drop of my blood more precious than the entire Turkish state.”

Written between 1915 and 1916, the diary was published only in 2011 as Year of the Locust: A Soldier’s Diary and the Erasure of Palestine’s Ottoman Past, thanks to Palestinian sociologist Salim Tamari, who rescued it from obscurity. On the question of Palestine, Turjman writes: “But what will be the fate of Palestine? We all saw two possibilities: independence or annexation to Egypt. The last possibility is more likely since only the English are likely to possess this country, and England is unlikely to give full sovereignty to Palestine but is more likely to annex it to Egypt, and create a single dominion ruled by the khedive of Egypt.” As it turns out, Turjman was wrong.

The diary had a strong emotional impact on Joreige:

It’s because of that edge that I felt the need to go back to that historical moment, because now we know what happened then, and when they were studying this moment back then, when you look at the diary of Ihsan, he doesn’t know what will happen to Palestine, he speculates, he thinks that maybe Palestine will go to Egypt under the British. We are now at a moment when we constantly speculate, what will happen to the region if the Americans and the Iranians sign a deal, what will happen if the Russians leave Syria?

At one point, Turjman writes that a fellow officer in the Ottoman army declared his love for him and even followed him home. The diary ends shortly thereafter. As it happens, Turjman was murdered, at the age of 23, by a fellow Ottoman soldier in 1917, toward the end of the war.

Joreige has often wondered about Turjman’s violent end. In her Perambulation piece, she reflected:

Was this a passion crime committed by the soldier in love with him? Was there an issue related to money or any other personal matter with the murderer? Was it an accident during a heated fight? Much of the ambiguity remains until today. Thus, Ihsan will not know about the end of the Ottoman Empire, he will not know the outcome of the war, he will not see Allenby entering his hometown Jerusalem, or the fate of Palestine and the conflicts that will later unfold in this region.

Throughout our conversations, Joreige insisted that in spite of all appearances to the contrary in our daily lives, historical events are not predetermined, but the result of people’s actions. This position echoes that of political theorist Hannah Arendt, who argued that the idea of necessity in history erases the freedom of human action itself. In her essay “The Concept of History” (1961), Arendt tells us that every action is the result of human initiatives born out of the complex web of human relationships and is constantly interrupted by newer initiatives: “Every action that occurs interrupts predictable processes as something completely unexpected, unpredictable and casually inexplicable.” The conditions that led to “crystallized structures” of history, such as totalitarianism, were not inevitable, but became historical origins only after the event had already taken place.

In a conversation with the late Lebanese-American painter and writer Etel Adnan, which Joreige recounted in her Perambulation essay, she asked Adnan what would have happened had King Faisal I succeeded in ruling over an independent Arab kingdom. Adnan’s answer was ambiguous: “It might not have worked, but it might have worked. After all, even Lebanon worked, even Iraq exists, even little Syria existed, but it would have been shaky. The problems that Lebanon has, this Arab nation would have had them too. How can you manage such diversity?”

While our day and age remains uncertain, giving “Uncertain Times” that much more resonance, Joreige shares with Arendt a belief in a radically undetermined future, where action can potentially emerge, now or at some other time, and change the course of history: “What fascinates me are these moments of great possibilities — turning points in our history, where many factors and players converged and produced a radical transformation; where many directions and different outcomes would have been possible. I wonder if this territory could have remained unfragmented and under what conditions.” Joreige still ponders whether the remaining spark of the Lebanese uprising in 2019 will yet be snuffed out, something that seems more likely today, or whether it will bring about democratic change. She concludes it is too early to tell.

Ultimately, the relationship between past and present in Joreige’s work is not a continuous and linear flow of uninterrupted developments. It is constantly being reworked, not by the forces of history, whatever they might be, but through the agency of individual actors — for better or worse, we can never know.

- A conversation between Pelin Tan & Lamia Joreige with an intervention by Pr. Salim Tamari, moderated by Marie-Nour Héichaimé. Sursock Museum, Beirut, February 7, 2023.

- Independent Art Spaces in the Mediterranean Region: A panel with Emily Jacir, Lamia Joreige, Angelo Plessas & Laila Hida, moderated by Bouchra Khalili. ARCO FAIR, Madrid, February 24, 2023.

- Uncertain Times. Lecture-Performance by Lamia Joreige, curated by Pascale Cassagnau, LE BAL, Paris, March 23, 2023.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)