Select Other Languages French.

In the tradition of the literature of bureaucracy (think Kafka or Foucault), Egyptian novelist Shady Lewis breaks with many British conventions, daring to discuss race rather than class in the British system. This is one surprising tube ride that is filled with black humor and surreality of the immigrant experience.

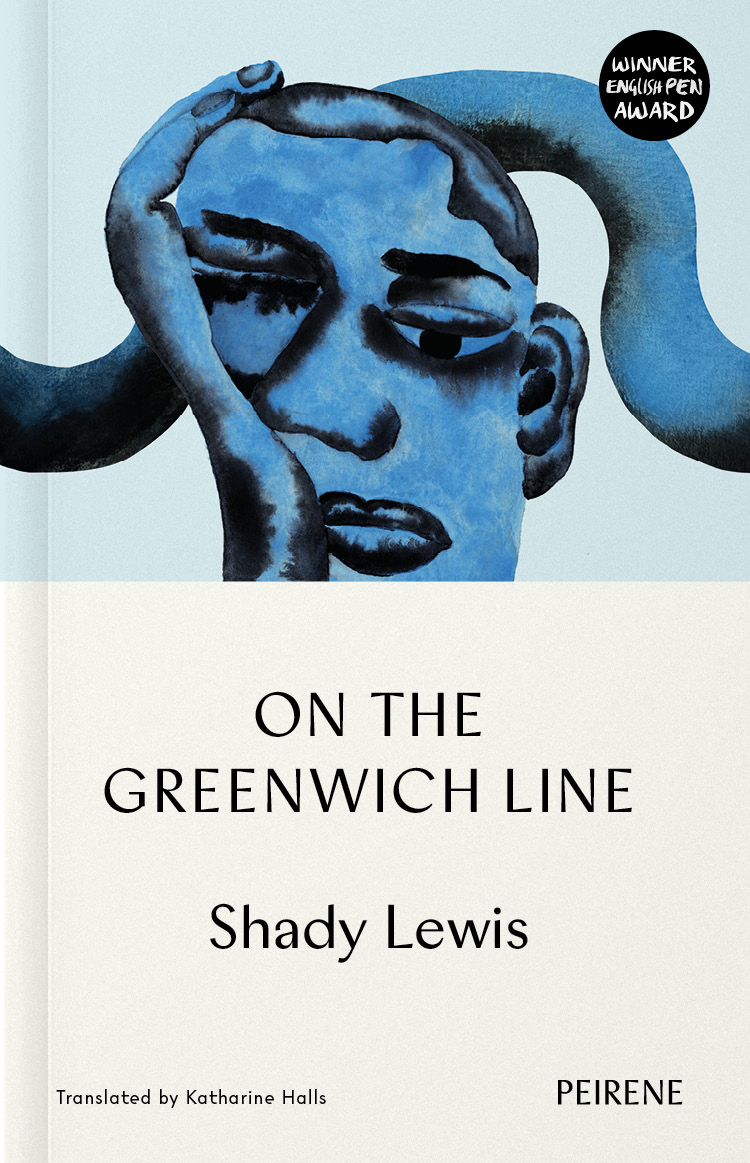

On the Greenwich Line, a novel by Shady Lewis

Peirene Press 2025

ISBN 9781908670953

“People like us will always be in-between in this city. Neither here nor there.”

With one foot on the right side of the Prime Meridian and the other on the left, the characters of Shady Lewis’s On The Greenwich Line philosophize on the immigrant experience. It is an identity as arbitrary and abstract as the Meridian itself, an invisible line cutting through East London that, by the conventions of British imperialism, comes to divide the world into East and West.

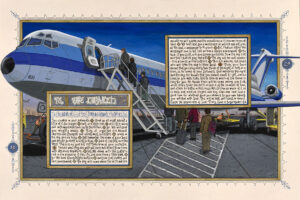

Labyrinthine bureaucracy, in-between identities, and, above all else, endless waiting — these are the conditions which Lewis maps out within the English immigration system. His novel, set over the course of just a few days, follows an unnamed narrator as he drifts through the monotony of his job in British social services, all while grappling with an unexpected responsibility: arranging the burial of Ghiyath, a Syrian refugee, at the request of his friend in Egypt.

The narrator’s begrudging acceptance of this task gradually begins to unravel his understanding of life and death, tugging at the apathetic boredom with which he first approaches the refugee’s story. Ghiyath’s impossible, pages-long odyssey out of Syria — traveling across multiple countries, evading execution, enduring torture, and weathering both natural and man-made disasters — is, remarkably, not enough to move him. After all, “there are a million similar if not identical tales, and ultimately these things get boring.”

Lewis’s narrator meets even the most horrifying stories with a sardonic detachment, a tone that will come to define the novel’s bleak but often very funny voice. As a cog in the malfunctioning machinery of British social housing during the age of austerity, he finds himself complicit in a system that perpetuates desperation, one temporary accommodation at a time. Lewis draws heavily from his own experiences as an Egyptian immigrant employed by the National Health Service, a position he held for many years. On The Greenwich Line was specifically inspired by diaries the author kept while working at a homeless hostel in London. Originally published in Arabic, Katherine Halls’ translation into English effortlessly captures Lewis’ biting tone.

What really horrifies the narrator is the lonely simplicity of Ghiyath’s death. The young man passed away quietly, alone in his room, his body discovered days later by his flatmate. The narrator is terrified by this dullness, ironic in the face of the refugee’s impossibly daring life. This discomfort echoes in his professional life, where his job is to keep people who have faced unimaginable tragedy placid within the monotony of waiting.

After the Conservative government slashed the social housing budget by more than half in 2010, the system restructured itself to manage scarcity. With a million people still on the waitlist, bureaucracy was lengthened into a maddening years-long process, as Lewis writes in the novel:

This long-winded administrative process sustained applicants through years of living in temporary accommodation and permanent poverty. Nourished by a combination of faith in the welfare state and wishful thinking that the process would produce the desired outcome, they remained hopeful throughout; the emblem of their hope was the yellow application form.

Waiting is not reserved only for those seeking social housing, as Ghiyath’s burial is similarly put on hold, caught in a system where even death calls for interminable paperwork. Within the first few pages of the novel, the morbid responsibility of the funeral arrangements is introduced and almost immediately deferred; the narrator returns to his daily life, disquieted by this brush with mortality.

Humor and drama

On The Greenwich Line is a short novel, following the narrator’s life in a small window of time. However, Lewis places his readers within the wandering mind of his protagonist, interweaving memories of Egypt, unsettling dreams and lengthy social observations within the prose. It’s through this meandering narrative that Lewis’ sardonic tone emerges most powerfully. Beyond its biting social commentary and poignant reflections on life and death, On the Greenwich Line is unrelentingly funny.

In one lengthy passage, the narrator reflects on the fact that most people assume that he is Muslim, despite him being a Christian Egyptian. He explains it away by saying, “Most people were well intentioned and only denied that I wasn’t Muslim because it disrupted the strict order that governed their world. I couldn’t blame them.” This pervasive racism is reframed by the narrator as yet another bureaucratic process — one rooted not in paperwork but in the mental shortcuts people rely on to navigate their biases.

Over time, the narrator ironically finds himself conforming to these assumptions: he stops drinking with colleagues to save money, adopts halal eating habits due to heartburn, and even begins fasting for Ramadan as a combination of stomach issues and surreal resignation. “This was much more comfortable for everyone around me,” the narrator explains, “restoring their peace of mind and reinstating the image of the world as it appeared to Border Agency officers.”

In a 2023 event at the Institut du Monde Arabe, Lewis remarked that he employed humor to “defuse the drama in our lives… if we can laugh together about the drama, it’s better than pitying people’s tragedy.” This philosophy underpins the novel, pushing readers to confront life’s absurdities and suffering without falling back on despair.

Lewis went onto describe On The Greenwich Line as belonging to a tradition of “administrative literature,” drawing on figures like Kafka and Foucault. But what sets the novel apart is how it intersects this literary inspiration with the surreality of the immigrant experience. Lewis’ narrator is not only navigating the nightmarish machinery of state bureaucracy, but also the unpredictable absurdities of life as an outsider — where one moment he is assaulted and called a racist epithet reserved for Pakistanis and the next he is cheerfully told, “Oh, you look very Egyptian. Straight out of the British Museum!”

Madness and philosophy

Almost everyone the narrator encounters is an immigrant — either on the receiving end of the housing system or managing it from within. The entire bureaucratic structure appears to rest on the shoulders of migrants patching holes in a ship no one else is willing to board. As the narrator puts it, “cleaning the rubble of society, sometimes looking for survivors underneath it and other times colluding to keep them buried — was not something any white person would be caught dead doing, much less down here on the lowest pay grade.”

Lewis approaches the insanity of their experiences by surrounding the narrator with a cast of characters who each turn to personal philosophy to make sense of their place in it all. In the face of structural collapse, everyone builds their own logic, their own coping system, their own private cosmology.

Everyone on the team has a theory. Pepsi, the only British-born woman on staff but of Caribbean descent, insists the narrator cannot be African because he is not Black. Despite never having set foot on the continent, she insists she is more African than he will ever be. Her personal philosophy involves the daily act of covering her face in white chalky powder. “If you are Black in this world,” she explains, “there are only two options: either you adapt and make your skin white, or you laugh at them.” With her white powder, Pepsi does both.

Then there is Kayode, the lead psychiatric nurse, whose only goal is to work until retirement so he can return to Nigeria and buy a house with a pool in the yard. The narrator notes that Kayode is always looking at photos of this pool on his phone, often during meetings, as though willing it into existence. Kayode is full of social observations and homegrown philosophies. One of many arrives as he and the narrator prepare for a routine visit to assess Service User A, a Turkish woman’s housing eligibility. Before they begin, Kayode shares a theory: everyone working in the welfare system is Black — and in fact, almost everyone in the world is Black. “There are black Blacks, Eastern European Blacks, Chinese Blacks, very black Blacks…” But anyone with a swimming pool, he adds, is categorically white. By that logic, Kayode insists, he will become white too — just as soon as he retires and gets his pool.

Addressing race so explicitly is somewhat unusual in discussions of British social systems. Convention would have the characters act more preoccupied with class, and while it can intersect with race, it rarely carries the same immediacy or intensity seen, for example, in the US. In centering race, Lewis destabilizes the way language is expected to function within hegemony, even in its critique.

The personal philosophies scattered throughout On The Greenwich Line, surreal as they may seem, offer each character a means of survival. Whether it’s Kayode’s taxonomy of Blackness or Pepsi’s white powder, these ideas form a kind of resistance against institutional erasure. Lewis never presents them as perfect answers, but their sheer recurrence suggests they are essential tools — ways of making sense, however imperfectly, in a world that refuses to.

Purgatory

Beyond the humor and absurdity of On The Greenwich Line, is its palpably purgatorial atmosphere. Of course, there is the endless waiting of those awaiting housing, but the narrator and his coworkers are also stuck in a strange state of limbo.

By opening the novel with the news of Ghiyath’s death, Lewis structures the narrative around a more literal form of suspension. A young man has died, and now he must be buried. But even the dead are made to wait. Administrative policies take precedence, and so too must his family wait: trapped in Cairo, dependent on a nameless, faceless authority to decide whether they will see their son one last time. Delays, paperwork, visa applications, case numbers — these are the latest frontiers of imperialism.

This atmosphere, however, extends beyond the circumstances of death. For the narrator, his coworkers, and the many immigrants entangled in the British welfare system, it’s tied to their unravelling sense of self. They exist in a prolonged in-between: not quite English, but no longer able to comfortably return home. To go back would be humiliating, but staying means settling into something harder to name. In an interview with The National, Lewis explained: “The narrator also sees that life can be good in Britain, but neither he nor the people around him can have that life. They can neither live well in their countries of origin nor have a good life in Britain.”

Ironically, the bureaucratic system offers a kind of grim solace through its cold, meticulous order. Before the narrator meets Service User A, he imagines her future death, knowing that her life would be quickly forgotten, and her body easily disposed of. But the massive casefile she’d leave behind would never disappear, it would become an emblem of her life, the only marker of her time on earth. “I felt pride, even elation, at the task I was about to perform,” he confesses. “I was the means by which this poor woman would be granted a certain immortality, or what in the office we wittily referred to as ‘administrative posterity.’”

Death, Lewis finds, has a strange power in our contemporary world. People are remembered by markers far more detailed than graves, whether they be case-files, Facebook pages, or haunting items they’ve left behind. Through the fog of this surreal attutude towards mortality, Lewis punctuates his novel with a few touching reflections on life and death. These moments can be quite surprising, being moulded out of the much more familiar sardonic tone emplyed by the narrator. Yet it’s exactly this contrast that makes it work so well.

The Meridian

On The Greenwich Line covers a lot in the short time we have with the characters. As the title suggests, it’s about the strange in-between — about a narrator suspended between lives, and the many people caught in that same space alongside him. It’s about the absurdity of bureaucracy and the quiet ways people learn to live with it, even rely on it. It’s about what it means to be an immigrant in an imperial country, working inside a system that will never quite make space for you.

A quality in Lewis’ writing is that he captures these contradictions without neat resolutions. His narrator is at once complicit and critical, detached and quietly moved. The novel is sharp, funny, and full of moments that sit uncomfortably between empathy and indifference. In the end, Lewis paints a brilliant portrait of the systems we accept and the strange philosophies we build to survive them.