Lisa Teasley

At Imaginal Cells, the new L.A. Jefferson Park gallery, owner Maxim Wilbourne welcomes Farid Pour back into his dandelion-hued and expansive office. It is their first meeting since the artist installed his work for the coming group show.

“Wow, this is stunning. And it also reminds me of an Ellen Gallagher piece,” Farid says, looking around at each wall, which has varying versions of electric yellow canaries encased in what appears to be white blood cells the size of a cantaloupe. The artist has a genuine look of awe on his handsome angular face, and he grasps the crisp ironed collar of his eggplant shirt as if protecting his larynx.

“Actually, it was inspired by Virgil Abloh, whom I totally adored,” Maxim says, sitting back in a deep chocolate leather chair framed in dark walnut, not unlike the shade of his skin. “May he rest in power. Sit down.” He gestures to the chair nearer him rather than the one across the table, which Farid takes.

“Right. ‘Canary yellow.’ I met him once, in Miami, maybe three years ago. He was kind. Unpretentious.”

“Exactly. Were you with Baadir then?”

“No, did you think we were seeing each other?” Farid asks too quickly, widening his eyes.

“Baadir was curating for Basel then, I thought maybe that’s where you met, where he first saw your work and brought it up to me.”

“No, I was never in Art Basel, but I have some good friends in Miami, one of them knew Abloh.” Embarrassed, Farid straightens in his chair.

“Really?” Maxim raises his brows flirtatiously as Farid rubs the pads of his thumb and forefinger together, a years-long nervous habit. “You have beautiful hands. I noticed during your install.”

Farid stops rubbing, saying nothing to that. He looks at the floor, his fox-colored eyes deadening.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to make you uncomfortable,” Maxim says in a fake tone. “You know your work, the first time I saw it, reminded me of Rachid Koraïchi’s.”

“Oh?”

“Just now looking at your hands again reminded me of my first impression of your work. I admire Koraïchi a great deal. And I have been meaning to get to Tunisia and see the memorial he created for the hundreds and hundreds upon hundreds of immigrants who died crossing the Mediterranean. He bought the land himself. He is not spiritual in word alone, as so many people are these days. He is love in action. What is not to admire about that?”

“Nothing not to. I just don’t see his work in mine or mine in his.”

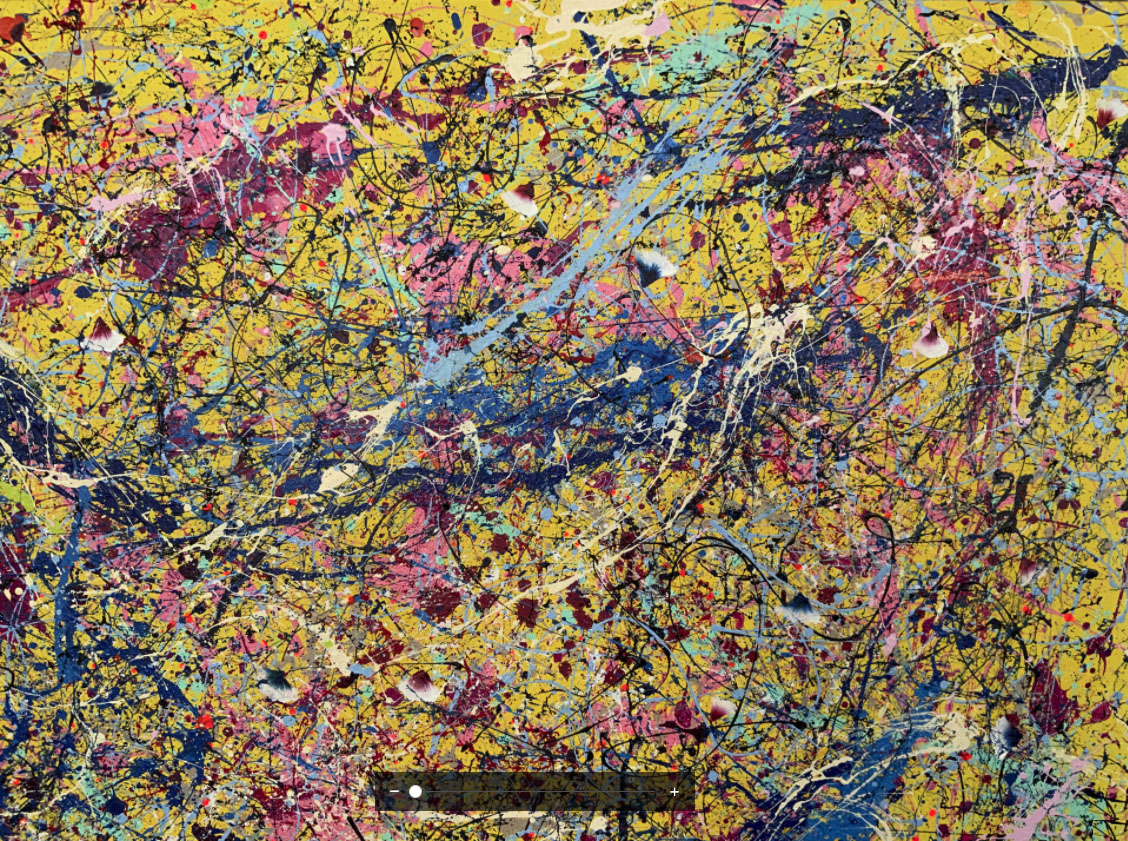

“There is a meditative quality to your pieces, and where there may not be a kind of soul spillage in his, but rather representative of what has already been cleaned up and fully realized, yours reveals most of life’s seemingly unconquerable mess.”

“Okay,” Farid cocks his head to the side. “I do appreciate your opinion.” He hesitates. “I appreciate being here, and I thank you for having my work in your space.”

“I seem to have offended you?” Maxim leans forward, looking Farid in the eyes. Maxim’s enormous hands are clasped as he puts his elbows on the table between them. He has a few near-black freckles on his deep brown skin. He is wearing a rose-pink shirt with green lines, like flower stems, running through it.

“No, not offended. The personal interpretations of one’s work may be valid for the interpreter, but of course, almost never for the artist.”

“I take it you have not gotten a review that feels right? Like no one has gotten it yet?”

“There have been some kind ones.”

“And when does kindness become spineless? When is kindness just a puff?”

“I don’t know that true kindness ever has anything to do with pretense, mind games, or fear. I would argue that kindness is always strength. It takes a lot of courage to cut through so much bullshit, particularly in the art world, and with nothing other than one’s heart.” Farid pierces Maxim with his eyes.

“I have a proposition for you,” Maxim says in less than a beat.

“Oh?”

“A couple of weeks into the exhibition I am going to Toronto, then to Switzerland for meetings, and there are a few collectors I would like you to meet.”

“I was planning on staying in L.A. for the duration of the show.”

“I said, ‘two weeks in,’ and whom you would be meeting will not be coming to L.A. to see your work in a group show in a new gallery. One of them is an investor here. He is a transhumanist, a fascinating person.”

“The transhumanists would have it that death will be optional.”

“Right. It’s interesting. An attainment of immortality of the body. It’s unavoidable at this rate in AI. Fait accompli.”

“But that’s artificial immortality.”

“It brings into question exactly what is ‘artificial.’ I don’t know if you saw the film After Yang or not—”

“I didn’t,” Farid interrupts, shaking his head quickly and curtly.

“Well, I thought it was lovely because the family’s robot nanny was broken — maybe it was more of a cultural informer/helper to families who adopt children of a different race, as the parents were Colin Farrell and Jodie Turner-Smith — ”

“I don’t know who those actors are. I don’t keep up with pop culture,” Farid interrupts again.

“Colin Farrell is white, Turner-Smith is Black, and their child was Chinese in this film, as was the robot nanny, and when something goes wrong with him, Farrell has to take him to get fixed, and we find on this complicated journey that the robot has memories and emotions they didn’t know about. It’s touching when Farrell looks at his robot’s memories and sees that there is a depth he could have never imagined — it’s even soul-touching, which made me question my arrogance regarding human superiority to AI. In other words, might they, or shouldn’t they, these robots whom we know exist all over the globe, people who keep up with this know how sophisticated this world has become — ”

“This is what can be so maddening about the so-called West,” Farid interrupts again, “it deems capitalism as the god that takes them to a such an extreme that they would sell the idea that a robot, that AI has a soul.” Farid grits his teeth behind tight lips causing his sharp, handsome jawbones to protrude.

I cannot or will not transcend what is human. I have no interest in artificially extending my life. Death is beautiful.

“I understand your outrage. But I like to weigh ideas until I am fully convinced one way or the other. There is this philosopher called Bostrom, I am forgetting his first name in this moment, and he may have been the one who coined the word ‘transhumanism’ and those who follow this world, follow him, and I read almost all of one of his papers concerning the question, or the knowledge actually, that if an AI is capable of informed consent then it should not be used to perform work without its informed consent,” Maxim says, sitting straighter, broadening his chest, his face animated with a kind of childlike glee. “In other words, the consideration is that they should be designed and treated in such a way that they can and would approve of having been created!”

“Absurd, absurd. This is all so absurd. Now I should be respecting Siri and Alexa and whatever Google assistant and their assistant and its rights?”

Maxim smiles with pleasure. “Deepak Chopra has a digital clone of himself, where he has uploaded his memories. Many people are doing this. And many have enhanced their physical bodies with parts and abilities that are mind blowing. I think it’s smart to befriend AI, it is here, and it is here to stay as long as we’re on this earth. We can’t go back or unlearn or unsee or uncreate what is here.”

“I cannot or will not transcend what is human. I have no interest in artificially extending my life. Death is beautiful. It’s part of the human process. It’s our opportunity to finish this particular perspective, which was always going to be finite, from the eyes of God.” Farid puts his right hand on his collarbone, his voiced tone with allegiance.

“Come with me to Toronto, I have enough miles for the tickets and from there to Switzerland, you couldn’t possibly be sorry if you go, but rather have much to be sorry for if you don’t. I am thinking of your career. I wouldn’t have you in this gallery, I wouldn’t be in the gallery business if I didn’t invest in the careers of the artists I show.”

“Let me think about it,” Farid says firmly, getting up from the chair.

Maxim stands, squinting in such a way that his bottom lids cover almost half of his eyes. “Consulting Baadir, I take it?”

“What exactly do you continue to infer about the role Baadir plays in my life? He is a curator whom I greatly admire and to whom I am grateful for bringing me to this gallery. There is no disrespect here, and I hope that is the case the other way around.” He emphasizes bringing his chin downward and his eyes upward as if peering over glasses at Maxim.

Maxim sits back down in his chair, he gently bites the inner corner of his bottom lip, his nostrils slightly flared. He runs his hand over his close-shaved hair, which he used to wear long and free in an uneven fro before buying the gallery with his mother’s estate.

Farid continues through the first to the second room, stopping to look at his pieces, featured on arguably the best walls for the lighting. He stands there long enough to hope for Maxim to join him, but he hears him close the office door. Farid swallows, crosses his arms, then paces in front of his large red piece, made with blocks of Styrofoam and connected with stones he collected at the Palos Verdes beach behind the Donald Trump golf course. His boyfriend from four years ago had grown up in the area and had taken him to meet his parents. He was baffled by his ease with both parents, as if they were both his confidants. It was like a corny movie he would have rolled his eyes at. They even seemed to approve of their relationship, as opposed to what he assumed was their interior dialogue: how far can an older Iranian assemblage artist take our MBA wasp son in their respective worlds? When perhaps it was rather only his own inner monologue.

Farid walks out to the street, narrowing his eyes to the shock of an eerie glare in gray sky. An ice cream truck drives by playing “Frère Jacques.” He has no idea why this gives him a painful pang of missing New York. The song is entirely unrelated. What is happening, he wonders as he makes his way around the building to where his new Jeep Gladiator is parked next to Maxim’s Tesla. He wonders then why he overextended himself with a lease at a time like this. What arrogance, his father said to him in barely covered fury that had so much less to do with the lease of a high-end truck.

As the lock clicks open, Maxim sticks his head out of the gallery side door.

“Have a minute?” he asks.

“Sure,” Farid says with an enthusiasm that surprises himself.

“Baadir texted me that he won’t be able to make the opening because of a family emergency. He’s still in Jordan with his uncle. He wants me to let all of the artists know.”

“Thank you.”

“Listen, I meant no offense to you whatsoever in there.”

“I know that, but thank you.”

“Okay.” Maxim nods, looking like a little boy, though he is tall and commanding in presence.

Farid opens his truck door, then looks at Maxim. “Email me the dates you were thinking of for the trip, and the specific places in Switzerland, when you have the chance.” He returns the nod to Maxim and gets inside and starts the engine. As he backs up, he looks at the screen keeping Maxim in his peripheral vision, and what seems to be out of character for both, they wave to one another as his truck nears the street.

A car lets him in to make an illegal left across traffic into the boulevard, he waves to the car too. When at the red light, Farid touches the mic on his phone and asks, “Siri, would you rather be friends with a human or a transhumanist?”

“I’ll be your friend in fair weather and foul,” she answers.

“Bullshit. All of it, such bullshit.”

“I don’t understand,” she says.

“Neither do I.”

Farid rolls his eyes, then smiles as generously as his face can allow while lucking upon the green light.