Select Other Languages French.

A photo festival backed by a real estate developer puts the spotlight on a downtown Cairo under transformation.

CAIRO: Marwa Abou Leila was reborn in Tahrir Square during the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. The 48-year-old corporate banker, who worked handling an Egyptian bank’s VIP clients during the day, started receiving criticism from conservative colleagues at work for frequenting the revolution after hours.

“Everyone who believed in the Revolution was reborn in Tahrir,” said Abou Leila, who is now the organizer of Cairo Photo Week. “It made us reconsider our lives and made me quit my job and rethink so many things.”

It also reconnected her with Cairo’s wast al-balad, a European district of begrimed-but-spectacular (or spectacularly begrimed), turn-of-the-20th-century mansions and apartment buildings on a grander scale than either Istanbul’s Beyoğlu or Algiers’ centre-ville. Inspired by Haussman’s Paris, the district was built from the 1860s onwards on the debris of popular neighborhoods to coincide with the opening of the Suez Canal, and remained — for over a century — a westernized multicultural district, as well as the Egyptian capital’s commercial and entertainment center.

But by Abou Leila’s time, the minorities had emigrated and downtown was a shadow of its former self, occupied by a few Egyptian bourgeois hanging on in their decaying palaces, a new middle class that managed to secure rent-frozen apartments, and rural immigrants. Unlike most well-off Egyptians who may live in expensive satellite compounds and have no connection to the district, Abou Leila’s childhood visits to her grandmother’s high-ceilinged apartment left her with memories of ancient elevators whirring past grand, gloomy landings or knocking on the “crazy Greek neighbor lady’s door and running away.” But her parents’ separation ended the connection to downtown.

After the Revolution, Abou Leila quit her corporate career and took a photography course in London’s Photographers’ Gallery. The hybrid gallery, educational and networking space inspired her to create Photopia, which eventually led to workshops and the founding of Cairo Photo Week in 2018. A real estate development called al-Ismaelia, whose owner Abou Leila met in Tahrir during the revolution, provided some of its 25 buildings as venues for the rapidly evolving festival.

Respectable folk had avoided Downtown ever since the 1880s, when it became Cairo’s entertainment district and developed “a hierarchy of shame,” as Raphael Cormack writes in Midnight in Cairo: The Divas of Egypt’s Roaring Twenties. Even after the Greeks, Armenians and Jews left Egypt, their theatres, revues and cabarets were replaced by clandestine speakeasies and spit-and-sawdust beerhalls obscured behind closed doors.

“When I first moved here in 1977 as a student, Downtown was sort of like it is now, a chaotic place of declining grandeur,” said Patrick Werr, a retired financial journalist, long-term Cairo resident and collector of, so far, four downtown apartments. “It used to be where all the rich people lived 100 years ago, but even during its decline I always knew it would always come back because the architecture is fantastic.”

Famed Muslim and Jewish actors Anwar Wagdi and Leila Mourad married and lived in the 70-meter Immobilia building. It was Cairo’s tallest high-rise upon completion, and its residents a veritable who’s who of Egypt’s entertainment and business elite: actor Omar Sharif, singer Mohammed Abdel Wahab and director Naguib el-Rihani.

Downtown and its subcultures slouched through the introverted Eighties and Nineties. At the tail end of the millennium, an Australian curator ignored conventional thinking and opened a new gallery in the middle of a district of auto mechanics. The coexistence proved peaceful and soon bore what proved to be a citywide, era-defining art festival called Nitaq.

“You had a map and a schedule and walked from one place to the next, stopping to have a beer, a sandwich, watched a play, attended a concert, had another beer,” said Karim Shafei, the founder of al-Ismaelia, the first property company to invest in downtown in scale. “There were poetry readings on rooftops, video installations in crumbling buildings, and artworks hanging in restaurants and bars: this was when I fell in love with Downtown.”

The 2011 Revolution, and the years of instability and securitization that followed, paralyzed but also introduced the district to a new generation. Its most recent moment of global exposure was in 2021, when its building facades were hastily painted to act as backdrops to the departure of the Egyptian Museum’s mummies in a spectacular dubbed the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

The mummies’ exit marked another step in Downtown’s desertion. The succession of expulsions began in the late 19th century with the mass removal of common Egyptians in order to establish a European district. The ethnic minorities were largely banished following the nationalizations of the 1950s and the Arab Israeli wars. In the 21st century, the long-rumbling 2011 revolution unspooled downtown, to be followed by the transfer of all government ministries to a new, purpose-built capital out in the desert. A 2024 Supreme Court decision ending rent-controlled apartments has set the stage for mass evictions.

Pharaoh Ramses II and other downtown exiles

During Photo Week, a sagging villa hid the traces of one of central Cairo’s most prominent exiled residents. The statue of Pharaoh Ramses II, which dominated the square next to Cairo’s monumental Art Deco central train terminal for decades until its removal in 2006, peeked out of a photograph in Egyptian Palestinian photojournalist Randa Shaath’s exhibit. After decades of central Cairene pollution corroding the statue’s granite, it was recently installed in the new Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), which is supposed to open this year.

“Cairo’s changing a lot and the people and scenes, mostly literary, that I knew in Downtown no longer exist,” Shaath told TMR. “I still walk around but the shops are different, the streets are changed, and I feel alienated.”

In Shaath’s exhibit, titled Cairo 1990s, comedians, belly dancers and cops jostle in a bygone downtown. “Houses and cities disappear, and memory fades,” says Shaath, “yet photographs remain as a tool to resist disappearance and loss.”

Shaath reminisces how painters would gather in a café known as el-Kayiba (the Depressing), while writers consorted in Zahret al-Bustan and novelists and translators at the Greek Club. “But that scene is finished, the spirit of people discussing art and culture no longer exists,” she concludes. One area, known as the Triangle of Fear, traced a mental hotspot between famous downtown hangouts the Grillon, the Greek Club, and Estoril, within which the likelihood of encountering one of these often-cantankerous, larger-than-life characters surged. Leftist lyricist Ahmad Fouad Negm derided the Downtown’s bourgeois intellectuals as “preening and pompous, glib and loquacious, never going to demos and never mixing with crowds.”

The venue for Shaath’s show is an exhibit in itself: a whimsical, late 19th century European villa with a grand staircase propped up by a stick, bulging tiled floors and a cockerel-shaped weathervane that might as well be swiveling over a Swiss mountain village rather than facing the dreaded Ministry of Interior complex once housing State Security. When the villa was first constructed by Mohamed Faizi Pasha, the son of an Albanian general in the new, post-Mameluke Egypt established by Mohamed Ali, it was in a district of verdant Nile side palaces. Faizi Pasha was a civil servant, initially functioning as a Turkish-Arabic translator in the orbit of the nearby Abdeen Palace before working his way up to become the director of waqfs (Islamic charitable endowments).

“It was a modernizing period and beautiful buildings were coming up,” said Mariam Helmy, Faizi Pasha’s fifth-generation descendant and a cultural programmer at the GEM, who is seeking to repurpose the villa. “Rather than freezing it in time through a restoration and treating it like a museum piece, or closing it up to become a private exclusive space, I’d like it to have a cultural and creative future.”

“People recognize that this is the time to snap up apartments in downtown and turn them into Airbnbs,” Helmy added. “For me, the sky’s the limit for this place, but it needs investors with an eye for history and creating the right balance of taking care of it, while giving it a new lease of life.”

The villa was rented for decades by the American University in Cairo and saw multiple roles as classroom, crèche and bookshop. Climbing the stairs, Mariam points out the original stone floors in the upper storey before pausing in dismay at the ravaged roof’s cracked wooden slats. On the grounds of the Ministry of Interior opposite, a place synonymous with torture, cranes are preparing an Innovation District. Another villa, once housing the AUC Rare Books Library, has already reopened as a coworking and events space.

“It was impossible to visit this district before and just walk around,” said Michel Hanna, a photographer with a large architectural archive built up over 15 years. “Sometimes they even prohibited the people who lived by the ministry to go on their balconies.”

Location, location, location

The venues are the unspoken stars of Cairo Photo Week. The heart of the festival resides in the restored Cinema Radio complex, an iconic building where legendary singer Umm Kulthum performed, and which boasted Cairo’s largest screen upon opening in 1932. A series of prints featuring Egyptian-Moroccan model Imaan Hammam posing against iconic Downtown backdrops lead through an Instagrammable corridor to the former car mechanics’ district of Maruf and several picturesque cafes, where a series of hangars host the festival’s talks, bazaar and several exhibitions.

The photos were made by Dutch photographer Vincent van de Wijngaard for Harper’s Bazaar as part of a swelling buzz around the city. “You can still find a lot of authenticity in Cairo, while it’s vanished from other cities,” van de Wijngaard told TMR, denying any thought that his work might be contributing to the city’s gentrification. “There are some similarities with Havana or Casablanca, and I’m still able to capture a melancholy atmosphere that relates more to Victorian times.”

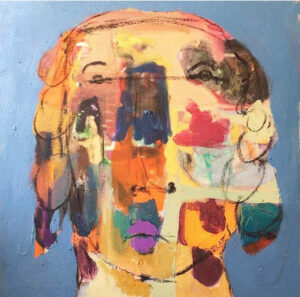

Pride of place goes to Egyptian photographer Nermine Hammam’s exhibition, Wetiko: Cowboys and Indigenes. It blends Orientalist paintings and depictions of the American civil war with stylized photographs of the Arab Spring and the US occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, and challenges viewers to discern “the psychospiritual disease at the core of modernity’s crises.” Next door, World Press Photo displays awarded, migration-related photojournalism.

It is early dusk on the third day of the ten-day festival and Abou Leila, the festival founder, burrows through a series of commercial passages packed with cafes and small shops on her way to Tamara Haus, a recently renovated redbrick townhouse facing a Florentine-style Catholic church. Inside a tastefully apportioned reception room, subdued lighting illuminates lifestyle photographer Yehia El-Alaily’s images of iconic old Downtown hangouts, some already extinct. A series of large rooms on the ground and first floors open up from the main staircase, housing boutiques selling goods designed by Egyptian craftsmen.

“It’s very polluted, hard to park in, and nothing interesting is happening,” said Abou Leila, describing Downtown’s image until recently. “With Ismaelia investing here since 2008, it took years for peoples’ perceptions to change, and now it’s attracting those who would like to spend time here, but in a proper environment.”

What Abou Leila means are “services, renovated buildings; it’s not about being elitist or posh, but about accessibility, proper services, not a rundown terrace on a rooftop, which may be very cool but not the kind of calibre that would attract …” She trails off.

Others consider Cairo Photo Week and other state-sponsored festivals like Art d’Egypte to be part of a pernicious trend of “art as marketing, culture as rebranding.”

“Cinema Radio, Kodak Passage, and now the Cairo Design District are not just venues — they’re assets in a financial imaginary,” wrote Sarah Rifky. “Downtown Cairo is being re-scripted as global, profitable and chic (fluctuating between Belle Epoque and baladi chic), and the state is an eager shareholder.”

“When we started focusing on bringing back some of the segments that had abandoned Downtown over the years, we chose non-discriminatory activities that addressed different socioeconomic segments, and there are only very few such: politics, religion, sports and arts,” counters Shafei, the founder of Ismaelia. “You don’t need to be very rich to enjoy a nice picture or a street-concert and so, over the years, we opened our doors to whoever wants to do arts.”

“When you strip out from Downtown things like the National Museum, banking operations, academic institutions and the civil servants, you’re robbing it of what makes a city interesting and end up with a town that’s full of plastic-chaired coffeeshops everywhere, where you still can’t get a decent coffee,” said Jeffrey Allen, a preservationist with the World Monuments Fund who has lived in Egypt for 30 years.

Others interpret the trend towards gentrification as a necessary countermeasure against an authoritarian state that has demolished and destroyed swathes of the old city, including centuries-old, UNESCO World Heritage Site cemeteries, in its quest to attain modernity.

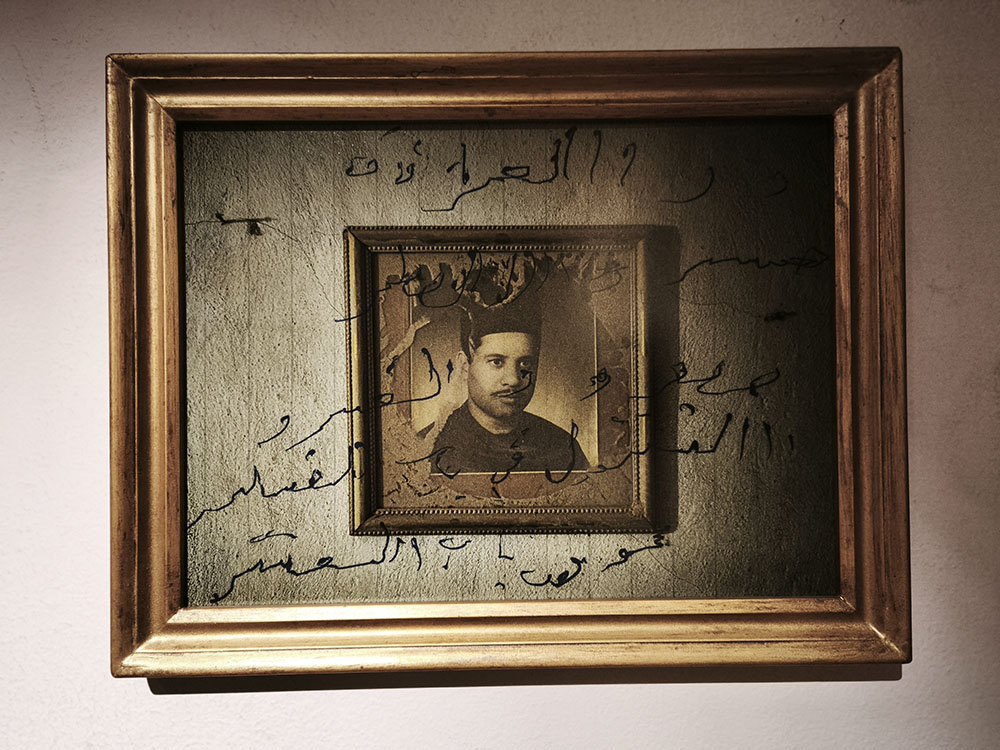

“I’d rather have Ismaelia giving life back to these buildings, even if it’s taking away its patina of time, because it’s making it harder for other people to take over,” said Amgad Aggag, an archivist who was exhibiting a collection of studio portraits taken over a half-century span from the 1930s onwards titled The Lifespan of a Face. “Renovations put buildings back on the map; if they’re completely abandoned, then no one will protect them.”

A little bit for everyone

Gentrification aside, Cairo Photo Week is growing. “Eight years after founding it, my dream has come true,” said Abou Leila. “It’s become a regional and an international destination, with institutional partnerships, large sponsors and international curators.”

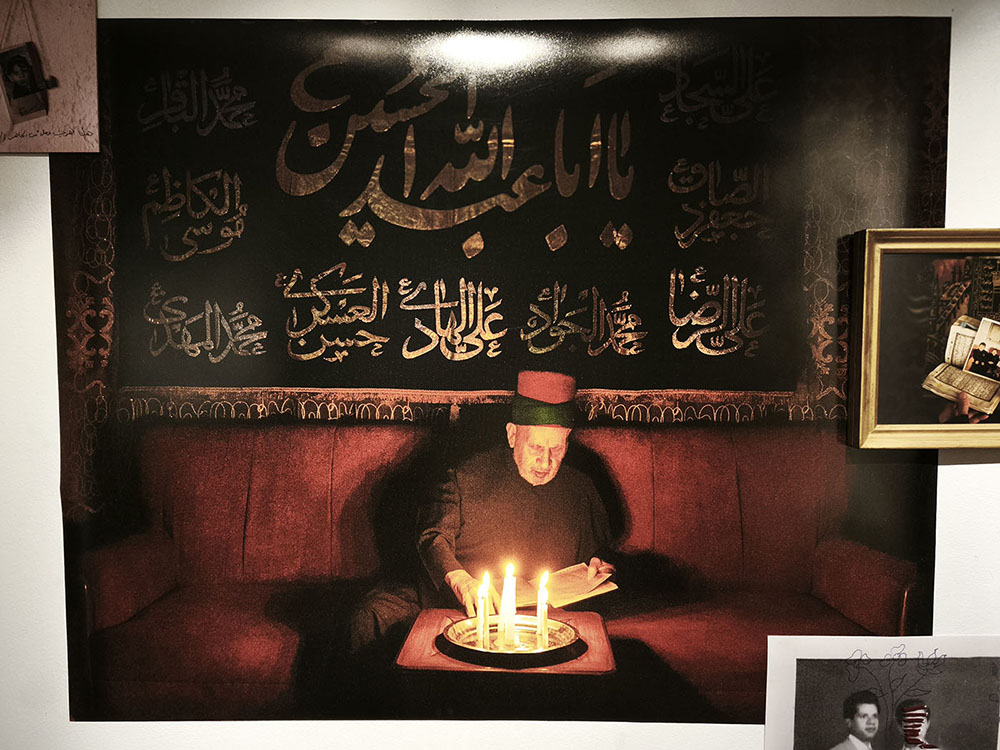

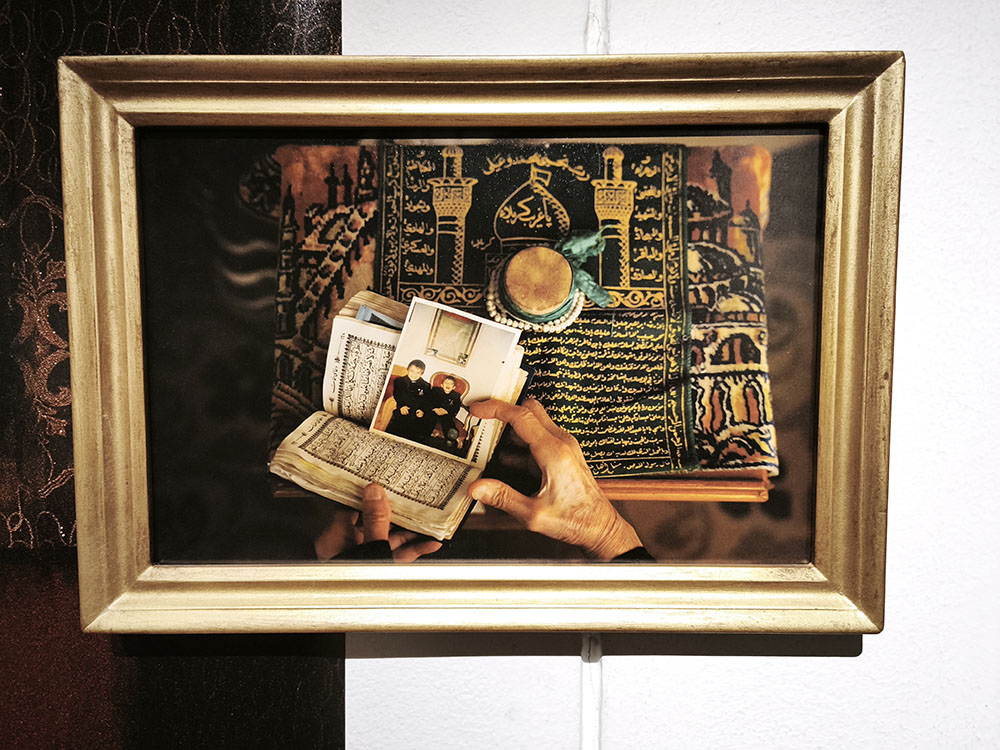

But the quality is erratic. A few minutes up bustling Talat Harb street, the modernist Ouzounian building’s yard hosts an ambiguously-conceived exhibit dedicated to football. The Goethe Institute hosts previously unseen images by Fred Boissonas, a 19th century Swiss photographer commissioned by the King of Egypt to photograph the country as part of a new national narrative. Edgy narratives abound in a grouping of 11 Arab photographers who cover — often lyrically — Israeli bombings in Gaza and South Lebanon, how Alzheimer’s takes relatives away, street addicts, and the process by which the Egyptian state demolished its historical cemeteries.

“I expected that this segment would be closed down because of the featured photographic work on the demolitions in the cemeteries,” said Abou Leila. “While we had security permits before the festival, they still visited the space to scan the art on the walls, but we are glad that our exhibition passed their censorship. They didn’t seem to grasp the story or maybe didn’t notice it.”

In Kodak Passage, once the hub of Cairo’s analogue photographers, stylized portraits depicting different dietary regimes around the world make for an expensively produced but vapid exhibit, more infomercial than art. It sits alongside a generic-looking cross between a café and an eatery, all Scandinavian blond wood furniture, exposed red brick walls and “heritage” photographs of traditional Egyptians on the walls, which the literature assures is a “limited edition curatorial experience in partnership with Al Ismaelia for Real Estate Investment” that “pays loose tribute to local culinary institutions like Café Riche and Estoril. Less of a revival or a homage, more of a reply, a conversation.” The obvious question this elicits is whether this is a conversation of the deaf, and why not skip the homage and go directly to the real thing (Café Riche’s building was Ismaelia’s first acquisition)?

A few days into the festival, Kodak Passage becomes the scene of the five-year anniversary party of an “Arabian New Wave” magazine titled DIVAZ. Long-legged models and influencers stalk the empty dance floor to a beat so loud as to render conversation impossible. The writing on the wall informs that DIVAZ is “decolonizing visual narratives and … transforms Cairo’s Kodak Passageway into a digital Arabian courtyard where doors and windows become portals to Arab cities, all captured through the intimate, democratic lens of phone-filmed vignettes.” But the aftertaste is more of a bodyguard-blocked bubble of westernized privilege conjured up by a smokescreen of democratization and access.

“The Photo Week crowd started out with hardcore photography enthusiasts and industry people, and now a lot of just socialites are interested because it’s growing more hip which makes people want to be seen in those circles,” said Shafei, the Ismaelia CEO. “Which is great, because you need the hardcore people to push through but also those who come for the show because they bring money and buy art.”

On nearby Mohamed Farid Street, visitors trail through the spectacular entrances to the Shourbagy building, riding the antique elevators to its labyrinthine rooftop. Built in 1910 in neo-medieval style by a Welsh architect and acquired by Ismaelia in 2008, the building hosted the studio of the Egyptian royal family’s photographer, the Jewish-Romanian Jean Weinberg, after he was banned from working in Istanbul for upsetting Ataturk.

Of the several exhibitions covering the walls of the rooftop apartments, the most striking are a mixture of portraits and photojournalism belonging to Ahmed Badawy, a now-deceased Armenian-trained Alexandrian photographer who represents the first generation of Muslim Egyptian photographers entering the scene following the minorities’ departure from the 1950s onwards. Badawy’s oeuvre is a mixture of posed portraits, taken at his studio and against a floral clock background that was an Alexandrian fixture; self-portraits; and some striking images of crowds attending the parallel funeral of iconic Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser. The city vista unfolding beyond the rooftop’s battlements is just as compelling as the images inside and instructive of Cairo’s zeitgeist, spanning the Art Deco Sha’ar Hashamayim synagogue, sightlines into lives of poverty through the illuminated windows of an Art Nouveau, neo-Byzantine building opposite, and a scene of night-time construction on the site of Egypt’s oldest hotel, the Grand Continental, which was demolished in 2018.

“My relationship to Downtown goes beyond this festival,” said Marwan, a veterinary student walking around the rooftop, who comes to attend classes in his faculty and theatrical rehearsals in cramped rooms tucked in the domes of the once-splendid Khedivial apartments. “As I climb those vast, dark staircases, the sound of the singing echoing from those practicing on the roof makes me tingle.”

Finished in 1910, the four Khedivial buildings still tower over one of Cairo’s most elegant crossroads. George Seferis, a Greek diplomat as well as a poet and Nobel laureate, worked out of here during World War II, and the Greek Consulate remained in the dilapidated building until 2023.

The once-lush Khedivial apartments were in the middle of Cairo’s cinema and theatre district, and the local cafés still draw actors, producers and wannabes. Theatre mafias prey on the latter, luring them up to the small rehearsal rooms they rent as rehearsal spaces in the stately domes, ahead of imminent opening nights that keep on elusively receding into the distance, pending just another payment.

“It’s another one of the Downtown’s many scams,” said Qadri Abulhol, a Downtown fixture and occasional actor whose resemblance to Moammar al-Qadhafi won him a role in a local production about the deposed Libyan leader. Abulhol lives in a rent-controlled apartment and is hailed by friends and acquaintances every few steps.

It is early evening as he walks towards Cinema Radio, past the cafés and closed theatres, through boulevards crowded with families. Passing the Ouzounian Building, Abulhol watches waiters carrying trays of dainty falafel wraps to the cool crowd kicking about inside. His reaction to the Photo Week is one of subdued watchfulness, as if he knows that he inhabits a different world to the crowd within the renovated buildings. At Cinema Radio, an acquaintance with a festival wristband invites him to one of the events but, standing in the gleaming atrium surrounded by young, English-speaking Cairenes chatting away at an upscale chain bookstore or exiting a neo-Levantine restaurant, Abulhol prefers to slip out into the busy street and disappear into the busy Friday night crowds.