Deborah Kapchan

“BJ Fernea is a wonderful woman,” one of my professors said, his hand on my arm as if confiding a secret. “Be careful though,” he lowered his voice as if BJ were in the room. “She is very conservative.”

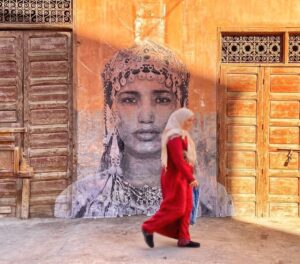

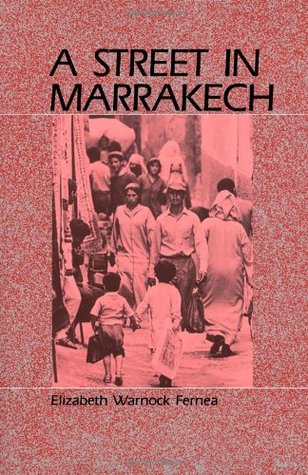

Elizabeth Warnock Fernea, aka BJ, was the former director of The Middle East Studies Association and the director of Women’s Studies at the University of Texas where I was about to begin my first job in the Department of Anthropology. I had read Fernea’s book, A Street in Marrakech, when I was working in Morocco a decade before, doing ethnographic interviews with parents in a study on children’s literacy. The job came with a ryad in the Marrakesh medina, a small library and Aisha, the maid. That sounds unusual, even unethical, to say that the house came with a maid. In fact, Aisha was not just a maid, she was a character in BJ’s films and books.

I did not ask my professor what he meant by this, or why he thought it was appropriate to warn me. I filed the information among the other things I had to remember as a new professor, and set off for a new life in Texas, with my husband Yahya and our five year old daughter, Hannah Joy. Because of a condition which blurred Yahya’s vision, I was the sole driver of a ten-wheel truck with a tow, heading south.

When we got to Austin, BJ immediately took me under her wing. She was a born mentor. She introduced me to people she thought I should know. She invited us home for dinner. Her husband, Bob, was an anthropologist in my department. They were among my closest colleagues.

Casa Fernea was in fact the salon of Austin. Whenever scholars or artists came through town, BJ invited them over. Despite her prim-and-proper appearance — a haircut like a nun, high collars and sensible shoes — she had a wry sense of humor. She could be quick in her judgments and got satisfaction when people appreciated her subtle innuendos.

She cooked Arab food, including the rice she learned to make in Iraq when she and Bob had lived there — fluffy and white, showered with pignoli nuts sauteed in butter. In her book, Guests of the Sheik, she wrote about how the village women — whom many in the West would consider “oppressed” — had pitied her because she couldn’t cook rice the Iraqi way. “Mister Bob is going to divorce you!” they teased. But she mastered that rice and many other things besides.

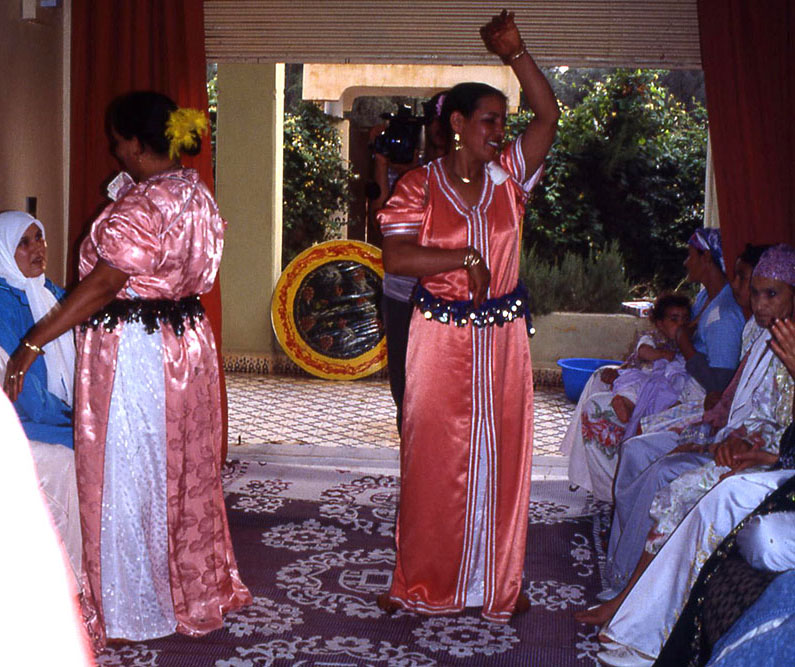

Not long after I arrived in Austin, BJ suggested that we make a film together on shikhat, women performers in Morocco who were often associated with prostitution. So much for her conservative nature. She had already filmed them in her earlier documentary, Some Women of Marrakesh, but they were not the central focus. I had written about them too in my dissertation.

In her film Saints and Spirits, she had filmed trance, and the pilgrimage to the sanctuary of Moulay Brahim where I also had traveled in my first weeks in Morocco. She had translated Amazighi poetry and published it. From my current perspective I see that all of my projects grew out of the topics I discovered in her books and her films, though I was completely unconscious of this at the time. No doubt she saw me as someone who would take her work into the future. She asked me to write a proposal to the BBC. When we got together to review what I had written, I was shocked. BJ had completely red-lined the text. She was a shrewd and demanding editor. She taught that to me as well.

We met in London the following summer, and went to the BBC studios where her friend worked. We viewed the first cut of the film she had just made: A Veiled Revolution: Women and Religion in Egypt. We never did end up making the film on shikhat, but we did meet up in Marrakesh the following year, with one of our graduate students, Sandra Carter.

BJ was now working on another book, In Search of Islamic Feminism: One Woman’s Global Journey. She already had a contract and a budget to travel all over the Middle East. Among other things, she and Bob were going back to Iraq to see people they had not seen for thirty years. Although the shaykh of the village had died, his children were still living, as were some of the women who had taken BJ under their wing.

For the Moroccan chapter, BJ came alone. She wanted to see Aisha, her former maid and ethnographic “subject.” It was Aisha who had taken BJ to the sanctuary in the Middle Atlas Mountains, Aisha who had guided her on the pilgrimage to the seven saints of Marrakesh. Whenever an American came to Marrekesh, BJ and others recommended Aisha as the housekeeper of choice. She spoke no English, so was very helpful with Arabic immersion. She was used to foreigners, and not shocked when men came to visit unmarried women. She cleaned and cooked with expertise. I met Aisha when I worked for the literacy project in 1984-85. I was a newlywed and Aisha was the maid that cleaned the ryad where we lived.

But despite the fact that she was the main character in BJ’s book and in one of her films, Aisha remained poor. She lost her job when the literacy project ended and the ryad was sold to an Italian painter. A few of us took up a collection and sent it to her by Western Union, but we suspected that her grown son, who was also unemployed, took the money for himself. Now we understood she was dying of stomach cancer.

I was living in Rabat that year, doing my research. Sandra Carter was, too. She was a graduate student at the University of Texas and was writing on Moroccan cinema. I was new in my tenure-track job, and she was at the end of her graduate studies. We were not far apart in age, and I saw her frequently. When I got to Marrakesh, BJ and Sandra had already spent a night at the Hotel Imlil, a three-star hotel that smelled like Baygon. I checked in and had the receptionist phone them to say I was there. After warm greetings, BJ suggested I take her place as Sandra’s roommate.

“Sandra can tell you about her new research,” she said. Sandra had not yet put me on her dissertation committee, but I knew all about her research, since we saw each other often in Rabat. Still, BJ was insistent.

“You both should really catch up. I’m happy to go to the other room.” She meant my room of course. She said this as if it were a magnanimous gesture. Sandra and I deferred to her wishes and I moved my things.

That night we went to dinner at a friend’s place. Rachida had been my co-worker in 1984-85. I thought she and her husband Abderrahman might know where Aisha lived.

We shared memories of Aisha as we sat around their table. BJ remembered her as lively and funny. Aisha had been much younger when she worked in the Fernea’s employ. She was BJ’s age and had four children of her own, but still lavished attention on the three Fernea children. Aisha’s husband did not have a job, and so she kept her family alive by working for others. BJ’s curiosity about Moroccan culture must have been a welcome respite from her life of cleaning. Aisha took her to the mountains to meet her family, to the public baths. She introduced BJ to clairvoyants and took her to popular weddings in the medina. BJ eventually filmed all of these things and wrote about them.

We went back to the hotel. That night I understood why BJ was so anxious to switch rooms. Sandra had a bit of a cold and was snoring quite loudly.

The next day at breakfast I was clearly exhausted and BJ and I exchanged knowing looks. After fresh orange juice, powdered coffee, and croissants, we took an envelope of money and headed to find Aisha, Abderrahman leading the way on his motorbike and BJ, Sandra and I following in a taxi.

Through the twists and turns of the medina navigable by car, we finally arrived at the northern gate near Douar Sraghna Cemetary. Here there were no tourists. It was poor and people stared at us as if we were from the moon. That we had an envelope thick with dirhams made us a bit uncomfortable; at least it did me. We went through the winding streets, asking directions several times, until we found her residence.

We knocked on the metal door first softly, then more loudly. Finally her son arrived. He was tall and thin, about thirty-five. Aisha had lost her daughter to illness decades ago. And her husband as well. Her other two sons were older and off on their own, but did not send her money.

We hadn’t told them we were coming. We didn’t want her son to prevent us from seeing her. We believed he had stolen her money, after all.

“Hello, we’re here to see Aisha, is she in?” I said in Arabic. “This is Beeja, the woman she made the film with years ago. I’m Deborah and this is Sandra.” Beeja was Aisha’s name for BJ.

“Salam,” he replied. “She’s not well. Come in.” And he opened the door.

Aisha was renting a small ground-floor apartment. Over the poured cement, there was a raffia carpet and two thin and worn sponge mattresses. There was a brazier in the corner. And a tall clay vessel that held water. That was her kitchen. The small room off to the side was her son’s.

She was seated on the floor. Bone thin, her cheekbones protruding like a skeleton, her hair wrapped tightly in a scarf. Her face lit up when she saw Beeja and she tried to get up, but pain prevented her. So we sat down next to her on the floor. Aisha told her son in Arabic to get some seating from the other room.

“La bas? Ki dayr-in? La bas alay-kum?” her voice was weak.

BJ’s Arabic came back somewhat. It was halting, but we were just exchanging formulaic greetings at this point.

“I’m very sick,” Aisha said. “Al-maada, my stomach.” I translated. BJ sat close to her on a low wooden stool, her face bent over her knees.

Aisha had no money to get treatment. But even if she had, at this point it was too late. She was dying and it was hard for her to hide the fact that she was in great pain. She nonetheless asked about BJ’s husband, Monsieur Bob, and their children by name. She asked about my husband too. I told her I’d had a daughter, Hannah. I didn’t mention the divorce.

“Muzyan, al-hamdu’llah, good, praises to God,” she said. Aisha had been our housekeeper during the first year of our marriage, our “year of honey” (sennat al-aasil). She had seen me go out of my mind with worry when Yahya didn’t come home after going to Casablanca for some papers. Was he sick? Had he been in an accident? There were so many fatal collisions on the roads in Morocco. People drove recklessly. Licenses were bought with bribes. Life was cheap. “Al-hadid, metal,” people would say, shaking their heads when people died, as if the fault lay in the material itself.

I imagined the worst. My life would end if Yahya had met with misfortune. When Aisha arrived the following morning I told her I had spent a sleepless night.

“He’ll be here by the afternoon, don’t worry,” she had assured me.

And that afternoon he had indeed arrived. He had missed the last bus to Marrakesh the night before and had stayed with a friend from college in Casablanca. There were no cellphones in 1984 and hardly anyone had a landline. When he came home I hugged him so tightly his thin frame almost cracked, while Aisha peered out from the kitchen, smiling. Those were my memories with Aisha.

It was clear that Aisha was making an enormous effort to be able to talk to us at all. By then her son had left the room. We were alone with her. This was our chance.

“Hak, here,” said BJ, folding the envelope discreetly into Aisha’s palm.

“Schwia dyal al-baraka, a little blessing,” I said.

“God bless you,” she said. “God help you. God protect you all.” These were standard blessings, but we understood them to be sincere. Still, we were not giving her a fortune. Maybe enough to get some medicine.

Once we were outside, Sandra began to cry. I put my hand on her back.

“It’s just so sad.”

“I know, and there are so many others like Aisha in Morocco, poor with no resources. Life is unjust.”

I said this, thinking not only about how “the poor will always be with us,” as Jesus said, but about how BJ had written a book and done a film that would have been impossible without Aisha. She was the anthropologist’s “informant,” and though BJ was now a professor at the University of Texas, living in a Southern home with columns out front, Aisha was in abject poverty and deathly ill. There was no justice in life. I thought of what a Moroccan scholar once said to me, that to be an ethnographic subject was the touch of death. He had pointed out several examples of this, of people who had died soon after their words and pictures were published by American anthropologists. Superstition? Chance? I shivered even though the weather was hot.

Of course, BJ had had her own struggles. She’d first gone to the field as the anthropologist’s wife, with only a Bachelor’s degree in journalism. She eventually wrote so many best-selling books, and was so active in professional societies that she surpassed her Ph.D husband in publications and fame. Lila Abu-Lughod said that BJ wrote feminist ethnography avant la lettre. Still, because she did not have a graduate degree, the University of Texas would not give her a job for many years. She struggled to make her place in a patriarchal academy. She never relented, and was finally awarded an honorary doctorate from the State University of New York.

BJ remained silent as we walked through the medina, back to the walls of the cemetery where our taxi was waiting. Little did I realize that she was writing this chapter into the book of her memory.

In the fall, all three of us were back in Austin. I began teaching “Anthropology of the Middle East and North Africa” and a course called “Hybrid Genres.” BJ went back to teaching and writing, Sandra to her dissertation. In January, soon after their famous New Year’s Day party, BJ presented me with some papers.

“Here,” she said. “I’ve finished my book. I put you in it. I hope you don’t mind. Read this chapter and let me know if you want me to change anything.” She handed me the print-out.

When we were in Marrakesh I knew that BJ had been in research mode, but I believed her interest was only in returning to see Aisha. I had never been a character in a book. Like BJ, I was used to writing about people, not being a subject in someone else’s story. Now I too was an “ethnographic informant,” though BJ had not told me at the time. But do anthropologists ever bring attention to our motives after we’ve mentioned the word “research” and can tell ourselves that we’ve been transparent? Do novelists ever mention anything to anyone when they are filing away the stories they go on to write? Perhaps that’s why BJ wanted a room to herself in Marrakesh in 1995: so she could write up her notes when we’d all gone to bed. (Though the snoring could not have helped.)

I hurried home and dug in, trying to keep thoughts about the fate of ethnographic subjects out of my mind.

Reading BJ’s account of our two days together in Marrakesh was unnerving. She narrated our time in detail. She talked about the dinner we had with my old colleague Rachida, and her husband Abderahman, and their two young children. BJ mentioned that it was Ramadan, which I had forgotten. Rachida had served us siffuf — a Moroccan sweet made from nuts, butter and honey. I didn’t think BJ was taking careful note of their behavior, analyzing their class and their gender roles, and describing the food Rachida put on the table. I didn’t know every moment was an ethnographic event — from what we ate for breakfast to my suggestion we buy blue-papered sugar cones as a gift for Aisha. (Large cones of sugar are broken with small iron hammers, and the pieces used to make mint tea.) As an ethnographer I got a taste of my own medicine.

More unsettling than the fact that I was being documented without my knowledge, was BJ’s vision of me. In the draft I appeared cold-hearted. When we left Aisha’s place Sandra had been bereft. But BJ described me as tough and unmoved. Is this who BJ thought I was? Could I tell her I thought her portrayal of me was unflattering? Instead I said, “Did I really say that to Sandra, that ‘there are a lot of poor in Morocco, Aisha is just one more’? That’s kinda insensitive! I don’t think I said it quite that way.”

Dear BJ. She understood. And when the book came out, her description of me was much softer. But I had learned my writer’s lesson that day: details can be rearranged. It’s the story that matters. And we all tell it from our own perspective.

BJ Fernea died on December 2, 2008. I choose not to believe that ethnographic subjects have premature deaths, though her life as an ethnographic writer seemed too brief. It turned out that my professor was wrong; BJ was not conservative. She was keenly observant, undaunted, and a fierce advocate for Middle Eastern and North African women, especially those who were her students.

Writing about those from different cultures and classes always comes with ethical challenges. BJ did not shrink from before them. She was a writer first and foremost, and her stories were hers to tell. We are all the richer.