A Moroccan Amazigh scholar from southern Morocco urgently tries to reach family in Ouarzazate after a frantic message from his distraught sister following the 6.8 earthquake that hit the Atlas Mountains region last Friday. The earthquake has caused widespread damage in the provinces and municipalities of al-Haouz, Marrakesh, Ouarzazate, Azilal, Chichaoua and Taroudant.

Brahim El Guabli

I was at an early work dinner on the East Coast when the earthquake hit Morocco on Friday, September 8, 2023. During dinner my phone kept unusually vibrating, but I could not pick up the calls anyway, so I just ignored them. When I got back home, I was surprised to see that there was a message from my sister, who usually does not call me at night. I knew something was wrong, but I thought it was just another family matter that she needed me to address with her. My sister and I have an agreement that she only calls me at night if it’s absolutely necessary. However, hearing the message, my sister’s voice sounded like it did when my mother passed away in 2017. My sister was emotional, distressed, scared, and most of all conveyed a sense of deep helplessness. She kept saying that the earth had moved violently, shook, and that our houses were cracked, and even saying that our childhood home was demolished.

I immediately scoured the internet for bits and pieces of information to just know what happened, but it was late at night in Morocco, and information was scarce. Pictures were blurry, and the magnitude of the damage was far from being known that late at night.

I tried to call my sisters and my brother, but none was answering my calls. The absence of responses from my siblings distressed me. It took me another hour or so to finally get a hold of two of my sisters. They were all out; they left their phones inside their homes, they explained. Their voices confirmed the shock, and the lack of understanding of what just happened around them. They were hit by the “earthquakian train” to paraphrase a Freudian sentence about trauma, but I got to hear how they experienced the moment when the world tremored from under their sleeping bodies. I got also to hear that our nine-month pregnant neighbor, Wafa, lost her life. Wafa’s story defies all logic in that she had been staying elsewhere and not gone home for over three months, but she went on Friday to pick up some items she needed for childbirth. That visit was fatal, and it saddened everyone.

Shocking videos starting to come through of what looks like entire villages destroyed close to the epicentre of the earthquake in Morocco

pic.twitter.com/kYu4tSO5MY— Emir Nader (@EmirNader) September 9, 2023

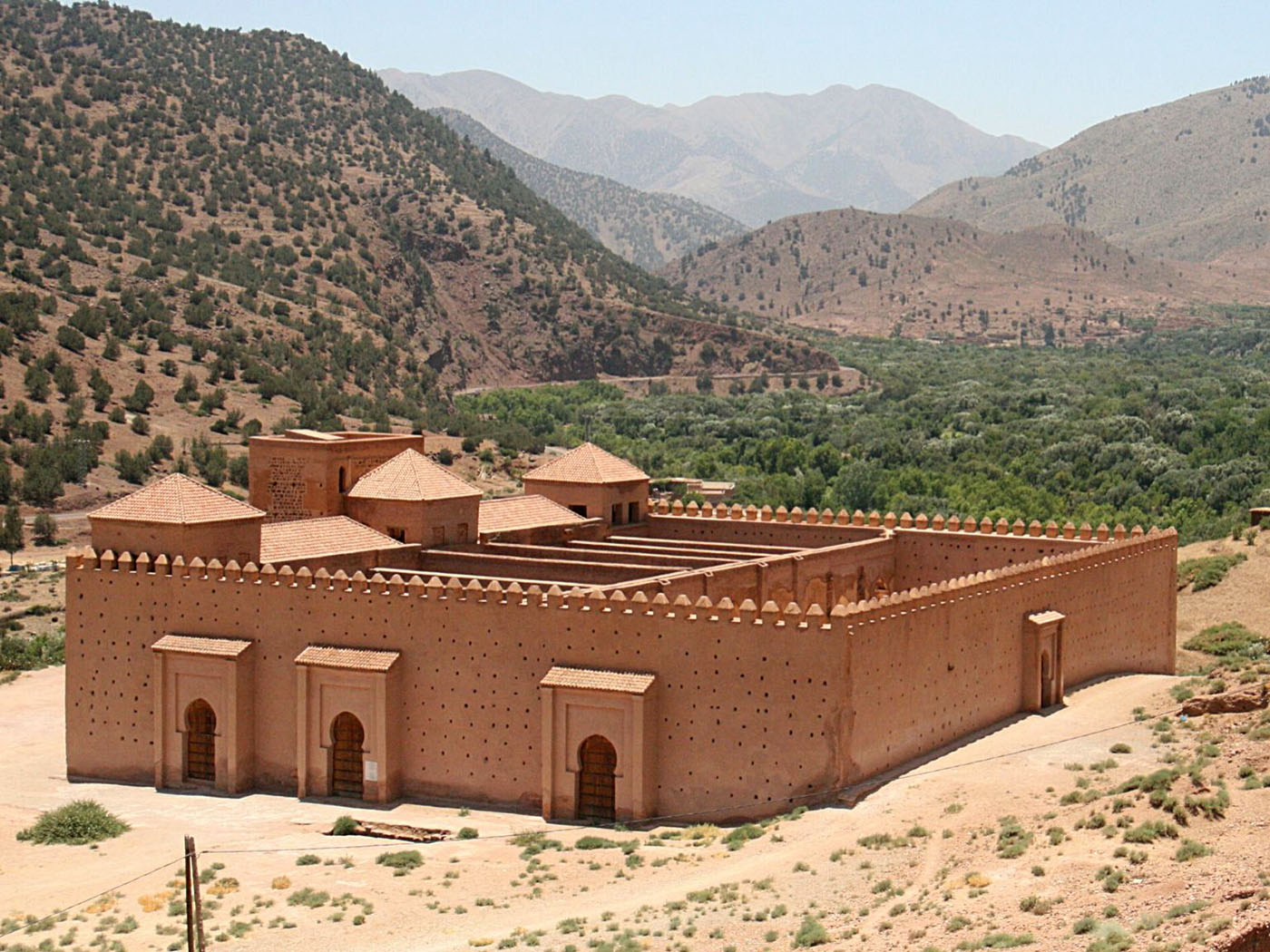

I grew up in a village that until recently was predominantly made of adobe houses. These adobe houses comprise the majority of housing in the High Atlas area. Adobe houses were made of 40 centimeter-wide and two meter-long molds. The heavily watered soil rests for a few days before workers poured into mold and pressed hard by a large batter made of wood to tighten the pieces of soils together into a one large unit. Because of this strenuous process, building an adobe house takes months. The ceilings were made of wood beams and bamboos covered with soil. This indigenous building technique has survived in the area for hundreds of years, and generations of builders have perfected it to build the famous kasbas throughout the south of Morocco. However, it could certainly not survive an earthquake of 6.8 on the Richter scale. As I see the piles of dried soil, wood beams, and bamboo sticks in the debris of demolished houses, I can’t but remember my work as a helper in the construction of house when I was a teenager. I have a close experience of the process, and I know that the building is really strong. I keep thinking of long gone masons who could build adobe houses, which a dwindling practice replaced by concrete and cement in most areas.

The End of Adobe Homes

The epicenter of the earthquake happens to be in area predominantly built in adobe. Apart from mosques and a few other houses, most people could not afford to rebuild their houses in concrete. These villages are mostly hard to access, making the cost of transporting cement and other construction materials prohibitive. Moreover, adobe houses are adapted to the climatic conditions of the people in the mountains. They are warm in the winter and cool in the summer. If the fact that most Moroccan houses do not have a heating system is factored in, it makes sense that people prefer the eco-friendly adobe housing to cement buildings. This wisdom is the result of centuries of living in these areas, and it proved its resilience against usual rains, flooding, and heavy snowfall. Since this part of Morocco has never seen an earthquake of this magnitude, there was nothing in living memory to ever push people to give up their ancestral style of construction. As a result, another sad thing about this earthquake, apart from the thousands who are dead, is that it will forever change methods of construction in the High Atlas. An architectural style may be lost in order to rightly protect lives against other earthquakes in the future.

While all of this was unfolding, I, in the United States, struggled to find my place. I am from there, but I am here, far away from everyone. As more information trickled in, I realized that I have a good knowledge of the area that was hit hard by the earthquake. I worked in many villages as a school teacher in the early 2000s, and I had a chance to visit many remote locations; exactly similar to the villages in which the earthquake wreaked havoc. I cannot think of any more loving, generous, and self-effacing people than the ones who inhabit the areas damaged by the earthquake. As somebody who hailed from a village closer to the city, much of the communal values that I found in remote villages had slowly disappeared from my own community. In the villages in Ait Zinb, Telouet, Tidili, and Ighrem, I found a stronger sense of solidarity, shared evening meals, and a common desire to partake in collective work in order to pave roads, build schools, and contribute to creating resources that would not reach the community if it were not for their own work. Because territorial management of development projects had forgotten about these areas for a very long time, their inhabitants created a parallel, self-reliant system to take care of their needs. They build and maintain their roads, they have their own potable water systems, and until recently, they collectively owned electric generators to light their homes. Theirs was and is still a life of communal solidarity.

The origins of these areas’ predominant economic vulnerability extend to all the way to the country’s independence. The period of state violence known as the “Years of Lead,” which lasted between the country’s independence in 1956 and the passing of King Hassan II in 1999, deeply impacted territorial development. As the Equity and Reconciliation Commission, put in place by King Mohammed VI in 2004, has demonstrated, state violence had left its imprint on the way development was distributed between the different areas of Morocco. Government focus was placed on the areas west of the Atlas Mountains whereas the Atlas itself and the areas surrounding it were neglected if not entirely forgotten about. This has created a lingering reality in which a place like Marrakesh has an advanced infrastructure while areas surrounding it are still stuck in rurality. The same can be said about Agadir and its surrounding areas. This territorial misdistribution of infrastructure is very clear in this earthquake. Villages in the High Atlas are impenetrable because of the scarcity of paved roads. Most of the villages out of the grid of national roads and instead rely on pistes (dirt roads). Aid is stalled and rescue and recovery operations have not yet reached the people who live further inside the mountainous area. A lesson that this earthquake can leave all of us with is the importance of connecting all areas, no matter how remote, with sturdy roads that will spare the country the loss of lives that could have been saved if roads were available.

Death is a Traitor

Another reflection that I could not dodge while thinking about the earthquake is the traitorous way it causes death. While I understand that death is part of life, death caused by an earthquake is treacherous in my eyes. It’s an untimely death that wipes out so many lives instantly and leaves no time for goodbyes or even for an understanding of what happened for both the dead and their survivors. An earthquake that strikes at night while people have returned to the safety of their homes is even more treacherous. It is a form of treason that brings death where it is not expected; in the sanctity of one’s bedroom. As I write this short essay, videos of survivors are proliferating online. People attempting to make sense of that happened to them and how their world transformed all of a sudden from a normal place to an image of a nuclear war scene. Some of my co-citizens have expressed their emotions in anger, and others in tears, but everything they convey converges in the tremendous tragedy that struck them, us, and everyone else who is touched by the devastation of a portion of our country. Lives unlived, childhoods cut short, children unborn, marriages unconsummated and plans thwarted come to my mind as I try to imagine how the people this region were expecting to spend the next week, the next month or the next year. An earthquake violently ended their plans and cut their lives short.

The earthquake has also shown me a wonderful face of humanity. People across the world have shared our pain and offered their helped to support the devastated communities. With my colleagues and friends Mounia Mnouer and Aomar Boum, I started a GoFundMe to collect funds for families. I am humbled by the outpouring of support from people we know and those we do not know, from those who are originally from Morocco and those are not. To all those who have contributed any amount their circumstances allow them to contribute, I address my sincere gratitude for their generosity. As the situation unfolds and the media interest in the earthquake decreases, my hope is that the world will not forget about the people in the ruined villages in Taroudant, El Houaz, Chichawa, and Ouarzazate.

Contribute to earthquake relief to the Atlas mountains region of Morocco.

I am in the United States and can not reach a close friend in Ouarzazate. Is there a list of the causalities?