Mo Baala, “La terre est bleue comme une orange”/“Earth is Blue Like an Orange”

Gallery 127, 127, Av. Mohamed V, Marrakesh, through October 30, 2022

El Habib Louai

In homage to French poet Paul Eluard’s poem “La terre est bleue,” with its dazzling opening line, “La terre est bleue comme une orange,” avant-garde artist Mo Baala is showing 365 collages through the end of October in Marrakesh, where he has lived for many years.

The Moroccan painter and multimedia creator fumbled through the long and tiring years of a tumultuous and at times heartrending childhood and adolescence. Born Mohamed Baala in Casablanca in 1986, he grew up in Taroudant with his grandmother Lala Fatima, living in precarious conditions resulting from the unexpected divorce of his parents. Like Guy Debord, who strolled the streets of Paris, Baala roamed the lonely streets of Taroudant, ducking into and out of his grandmother’s and others’ homes, seeking shelter from danger and sexual predators. During the day, he would venture into the narrow lanes of the medina, hoping to earn a few dirhams that would assist with household expenses. He did all kinds of odd jobs, ranging from shoe shiner, carpenter and porter to courier, bike mechanic and bazaar assistant. All this opened his eyes to diverse forms of con artist swindles, trickery, opportunism, favoritism and cunning in the open and free market of the old bazaar.

During his time at the bazaar, Baala started to read the great works of world literature and philosophy, works he often quotes today in his rich and engaging conversations with fellow artists and casual friends. Influential musicians who led the American Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and ’70s left an indelible impression on his character and his view of the shabby reality of his everyday world, even before he turned to visual arts. Through nocturnal conversations and long phone calls with me, he opened up on his experiences of social vices and inhuman treatment when he was employed in the workshops of carpenters and bicycle mechanics. Driven by a kind of madness that makes him a stranger to the actual wild world around him, Baala chose art, perhaps accidentally, as a means to create a different world that he alone inhabits, albeit with the consciousness of those who might share similar experiences.

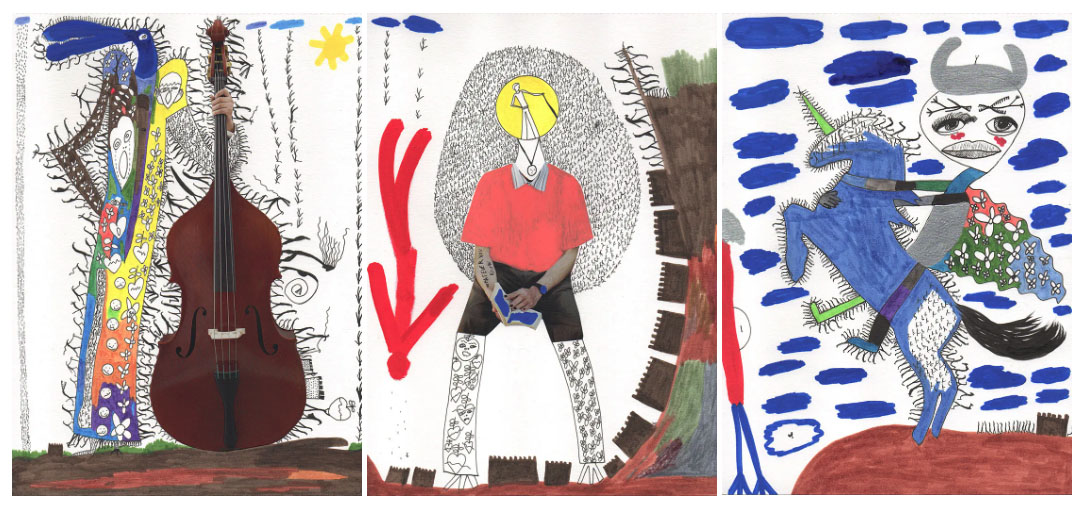

Lately, Baala has produced exquisitely intriguing works distinctive for their unique structure, texture and singular qualities. “Earth is Blue Like an Orange” includes the set of works he produced over the past two or three years, consisting of collages, drawings and overpaintings. The first set of his collages is composed of pieces of Arabic writing taken from a Pan-Arabic magazine called Al Arabi, published by Kuwait’s National Council for Culture and Arts. The font of the writing, its color and size change constantly, and it is sometimes italicized and highlighted in colors from the whole spectrum of the palette. The excerpted sentences and phrases are lined up horizontally in disproportionate rows. The space on the white page where the collages are dis/placed is used disproportionately, depending on the size of the phrases and the sentences’ font. Each collage is a significant landscape that lends itself to multiple interpretations.

Baala makes extensive use of the cut-up in his latest work. He cuts out readymade linguistic phrases and sentences from Al Arabi, and juxtaposes phrases and sentences randomly to create linguistic combinations that shock the reader with their irrational statements, connotations, striking wittiness and sarcastic effect. By rearranging the sections cut out from Al Arabi, Baala wants to enable different readings of a single text whose initial meaning was restricted by the frame of a mass media magazine with certain ideological leanings. His Arabic cut-up writing collages rearrange the elite journalistic and academic discourse to point to its bombastic ambiguities, falsity and manipulation of an absurd reality.

Collage n°1 for instance, opens with a blunt statement: “Satirists are not a threat anymore.” This statement is a direct allusion to the fact that writers and journalists can be unabashedly explicit, unreserved and sarcastic about any subject or issue in their society without being inhibited by censorship. Yet the ability to blatantly satirize and ridicule certain mundane situations and actions relating to social scandals and political transgressions does not necessarily mean freedom of speech in Baala’s world. The same collage criticizes the urgent call for the employment of young people in social, political, economic and cultural leadership positions when it says, “engaging young leaders.” The latter statement is followed shortly thereafter by “the educational farce” and “dualistic sectarianism” which clearly stand as a major obstacle to any real aspirations to establish a democratic state where different ethnicities, races and cultures coexist. It seems that what is needed in this postmodern world is a new “philosophical and cultural vision,” one whose proponents are unafraid to subvert “linguistic norms” and “failing politics,” as Collage n°2 states.

Some of Baala’s cut-up writing/collages deal with pressing global issues and problems relating to increased pollution, climate change and the resulting social disasters and environmental catastrophes. For example, Collage n°4 denounces the growing greed exhibited by capitalist corporations that long for “a good interest rate” while hoping to “invade and take over the sky.” Ironically, humans refuse to acknowledge that this world of ours “will always have its needs and wants,” irrespective of their greed.

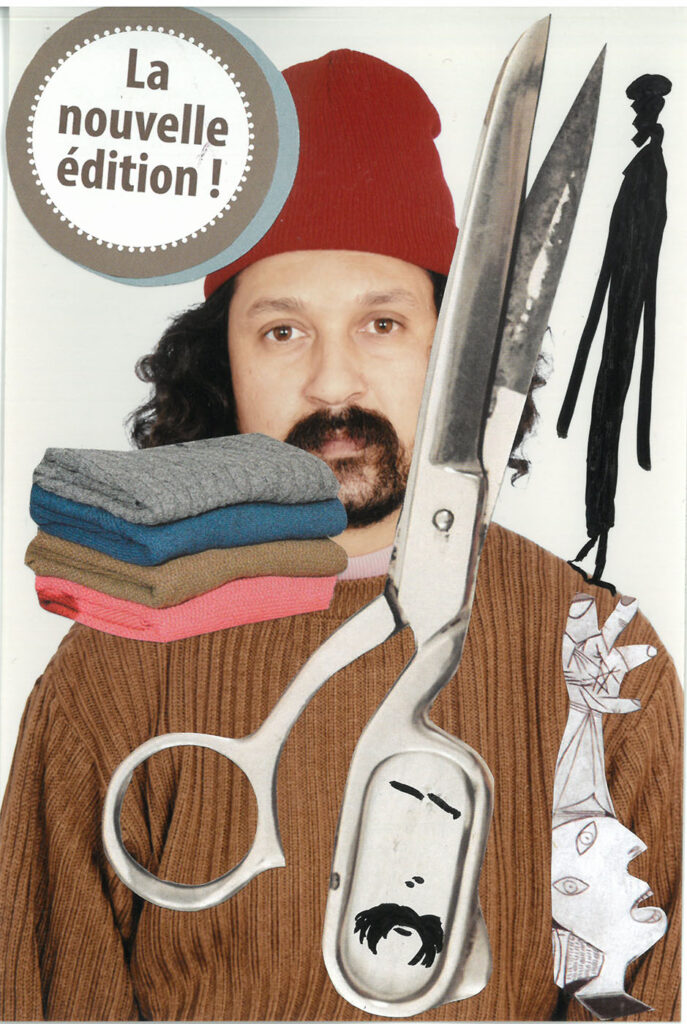

One set of collages is composed of a series of ID photographs onto which various cut-up images pilfered from elsewhere, digitally or physically, are pasted in various areas. In total, they are 60 pieces, with dimensions of 10cm by 15cm. The project bears the title “Show the Ears, Turn the Hat, Turn the Eyeglasses!” The ID picture, which is the principal element, defies ordinary conceptions of an official ID picture made for administrative purposes. The pictured character looks awkward — with his Frank Zappa moustache, his bristly beard and his fuzzy black hair tucked under a scarlet winter hat. His brown ribbed sweater, under which a light pink tee-shirt shows, seems to be a bit oversize. On top of this portrait are randomly scattered various elements: blunt and used scissors, a stack of orderly folded sweaters, a shadowy silhouette of a forlorn man wearing a kind of beret, shoes or trainers in different colors, an olive green inflated balloon with a black thread, organic limestone, a pressure cooker full of holes and the drawing of a football goal. All of these materials or elements (real-world objects, mass-produced images and ephemera) are gleaned from mass media magazines or journals.

Baala titillates his audience’s curiosity by juxtaposing scissors with neatly folded clothes, as this implies that the instrument should be used on the clothes. Baala’s work also criticizes the consumerist, unassuaged desire fed by the big fashionable brands that constantly create new editions of the same product as the seasons turn. Diversity in the kinds of shoes and trainers one buys reflects neither an authentic state of being nor a valuable truth about one’s individuality. By incongruously assembling unrelated photographs, Baala aspires to endow the individual with a certain kind of agency that will help destabilize choices offered by the fashion gurus.

Baala’s last collage in the series shows a bearded and partly bald Plato holding a book under his arm while pointing with his other hand somewhere up there, but ironically Baala places a cage on the tip of the forefinger that points to the sky. In doing so, he argues against the Platonic idea that the world of ideas would consist of an alternative perfect world, where justice will be served and peace will prevail, hence giving some hope to the subaltern and the wretched of the earth. The free birds, represented by the circling black and blue shapes drawn on the collage, allude to those individuals who constantly break out of their shells, out of their minds’ jails.

In a nutshell, Baala’s collage work in different mediums represents his critique of the reality that is available to his senses. His family history, his different homes, his subconscious and subsequent experiences in the competitively dangerous external world outside constitute the inexhaustible source of his creative works. Like Debord, he employs détournement to penetrate and repair the texture of the quotidian, whether by disrupting the received meaning of the iconic images and publicized slogans or by reconstructing literature inspired by the masterpieces of some of his favorite writers and artists. He is there behind Plato’s portrait gazing at the cage on the tip of his finger. He is suspicious of both the world of material consumption, dominated by modern conditions of production, and the seemingly opposite world of ideas that constantly change.