The prolific French-Algerian multimedia artist Kader Attia, whose work focuses on colonial and post-colonial history, trauma, and the spaces of repair, had his biggest event in Berlin with the Berlin Biennale.

Melissa Chemam

In 2021, when he was chosen to be the curator of the 12th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (June 11 to September 18, 2022), Kader Attia titled the edition “Still Present!” Early on, he expressed a desire to explore “how colonialism and imperialism continue to operate in the present” and to “decolonize the art world and museums.”

“There is a sort of principle of invisibility in Berlin,” Attia told me recently over Zoom, “linked to the reunification of the two Germanies, with the violence of the capitalist hegemony, which has resulted in a forced disappearance of the East’s identity, as well as the oblivion over Germany’s colonial enterprise.”

Attia wanted to invite German artists to the Biennale as much as artists from the diverse diaspora to be found in Berlin and beyond — the Vietnamese community, for instance, which he insisted was often forgotten. This community grew with the arrival of so-called “boat people,” refugees from the Vietnam war, Attia reminds us. But he also reached out to other exiles, from Asia, Latin America and of course the Arab world.

“I’ve been living in the city for about a decade,” he said. “I live in a ‘white’ area of East Berlin, where the aesthetic of the DDR [the Democratic Republic of East Germany, as abbreviated in German] is still present. Here is the former headquarters of the STASI [the former East German State Security Service, or state police], as well as diverse communities from the former socialist bloc, from Asia to Africa.”

Berlin has long been known for its vibrant Turkish community, as Germany and Turkey have built strong ties since World War I, which included opening routes for Turkish migration to Germany. But over the past ten years, with the Arab Spring and the war in Syria, Middle Eastern culture has become more represented across the city by Arabs than Turks. Some even speak of a special movement in Berlin of Arab artists in exile (see “Arabs in Exile: How Berlin became a new cultural hub”).

“When I go shopping, my nostalgia for Arab products is easy to satisfy,” Attia admits, “as there are very strong Arab communities in the city. There are many Syrians around here; most of them arrived from 2011 and the start of the civil war in their homeland. There are also many Lebanese and Palestinians who have called the city home for decades.” Attia, who is French and Algerian, welcomes them all. “To me, they all brought a diversity that was missing in the city,” he said. “Berlin became less closed up, and they contributed to decreasing the ‘white’ gentrification of East Berlin.”

From Paris and Algiers to Berlin, a decolonial journey

Born in Dugny, Seine-Saint-Denis, France, to Algerian parents, raised in both Algeria and the suburbs of Paris, Attia chose to leave the latter for Berlin about ten years ago, when the city was hailed as central to the world of international contemporary arts. There, he was offered many opportunities to exhibit, explore new ideas, and make use of a larger space for his studio and team.

His art education was very French, but also multicultural. He went to the École Supérieure des Arts Appliqués Duperré and the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, in Paris. Before doing so, he spent several years in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in various countries of South America. After his studies in Paris, he pursued further art education at Escola Massana, Centre d’Art i Disseny, in Barcelona.

Attia’s research led him to deepen the notion of “repair,” a concept he has been “developing philosophically in his writings and symbolically in his oeuvre as a visual artist,” as he puts it. To him, any system, social institution, or cultural tradition can be considered “an infinite process of repair,” to get over loss and wounds, to generate recuperation and re-appropriation. Repair should connect the individual to gender, philosophy, science, and architecture, and also involves people in evolutionary processes with nature, culture, myth and history.

His practice includes sculpture, film, works on paper, and installation, for which he was awarded the Marcel Duchamp Prize in France in 2016, followed by the Prize of the Miró Foundation (in Barcelona) and the Yanghyun Art Prize (in Seoul) in 2017. For two decades, he has been exploring themes of divinity and skepticism, loss and reclamation, beauty and atrocity.

He has researched colonial trauma and its antidotes, and in conversation, he cites an impressive number of philosophers, historians, researchers and thinkers, from Taoist Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu (especially his teachings about meaning and void) to Joseph Beuys.

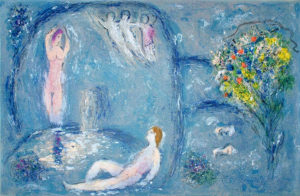

A recent solo exhibition of his was “On Silence” at the Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, Qatar, which was centered around his installation “Ghost,” from 2007, featuring rows of representations of Muslim women praying, rendered through shrouds of aluminum foil. Attia modeled the figures after his mother, keeping each one hollow, allowing for an eerie void.

His piece, “Untitled (Ghardaïa),” from 2009, shown at the Tate Modern among other venues, displays a replica of the eponymous ancient Algerian city, made entirely of couscous grains. The work is a reference to ancient African architecture and artifacts and how they often inspired Western architects, who failed to give them credit. Attia wanted to direct the viewer toward a reflection on the complex exchange between the North African aesthetic heritage and the region’s colonizers.

“Open Your Eyes” (2010), a double-sided projection of archival images culled from mainly Western museums, exhibited at the MoMA in NYC in 2012, introduced a juxtaposition of repaired artifacts with photographs of brutally wounded soldiers, while his work “Phantom Limbs” and the film titled “Reflecting Memory” addressed more directly the violence of war and colonial wounds. A lost limb, according to Attia, is “a political reminder, a way for the authority to perform its power.”

“Authoritarian neoliberal regimes create war victims, amputees who cannot afford prosthetics, while their physical and emotional trauma imposes fear on others,” he once said. “The loss in this case is caused by chaos and negligence. The cacophony produced by media shadows the real problem today in places like Palestine or Yemen.”

In 2016, he opened a Parisian multipurpose cultural center, La Colonie (stricken through on purpose) in order to take these reflections out of museum venues and bring them closer to the general public; artists, writers and historians were invited to hold free discussions, which were almost always well attended. Unfortunately, La Colonie was forced to close during the first wave of the pandemic. Yet Attia remained hungry for further discussions and confrontations — and Berlin proved a promising city to pursue them.

The centrality of Berlin

Attia has plans to reopen La Colonie in a permanent space in 2023, but meanwhile the events continue online. The Berlin Biennale’s program was conceived so that thinkers could contemplate ways of “de-colonizing,” “with a space of mediation” on topics within and outside of the art world.

Attia feels that, in his role as curator of the Berlin Biennale, he has a citywide platform to break down his decade-long discussions around repair and decolonization. Since the fall of the wall, Berlin’s reputation as an international art city has grown alongside its status as “party capital” of the world. However, Attia feels that the question of Germany’s colonial history was often overshadowed by the historically closer traumas of the Holocaust and the Cold War.

“Many citizens in the East perceived reunification as a form of neoliberal colonization,” Attia said at a Biennale press conference. “This is a part of history that has hardly been dealt with so far, but it comes up in several works in the exhibition.”

Some of the venues chosen for the Berlin Biennale, like Wilhelmstraße 92, the location of the Berlin Conference on West Africa of 1884/85, make links between the city’s history and German colonialism. Among the invited artists are Turkish feminist Nil Yalter; Jordanian photographer Lawrence Abu Hamdan; video artist Susan Schuppli; Imani Jacqueline Brown; Congolese artist Sammy Baloji, Iraqi artists Sajjad Abbas, Raed Mutar and Layth Kareem; and French photographer Mathieu Pernot. The Biennale also displays pioneering data and video research of the Forensic Architecture collective and a Russian airstrike in Kyiv.

“The conversations on decolonial practices are very different in Germany, Belgium, England and France,” Attia says. “In France, decolonial ideas are still considered as exogenous, as imported from the English-speaking world, especially the United States, or they are seen as linked to each specific colonial history, like in the case of Algeria. Both these ideas have truth in them, but no former colonial state has been exempted from post-colonial reflections.”

Germany was for much time more focused on Holocaust-related issues, Attia added, and post-communist capitalist neocolonialism, but has now also become an interesting place to take on the global conversation on the relations between the Global South and the North.

“It’s become bigger than a worldwide landslide now,” Attia insisted. “Colonial, post-colonial, neocolonial and anticolonial debates have reached the level of a universal conversation, all over the globe, especially in settlement colonies, like the United States and Latin America, but also in Europe and Asia. Colonialism is seen as what it was: a part of the modern capitalistic project. Now, an evolution is possible thanks to the global conversation we have all over the world, to decolonize universally repressive systems.”

And to Attia, Berlin is an interesting place for such conversations, like Tokyo and Thailand. It is not a mainstream Anglophone/American center, nor in the hands of an intelligentsia denying post-colonial reflections, as it is in France.

Yet the journey wasn’t easy, even in Berlin.

In mid-August, Sajjad Abbas, Raed Mutar and Layth Kareem pulled out from the Biennale, saying that curators chose “the display of wrongly imprisoned Iraqis,” referring to photographs by the French artist Jean-Jacques Lebel that showed tortured inmates at Abu Ghraib prison in their homeland. Which the Iraqi artists find disrespectful.

Attia and the artistic team of the 12th Berlin Biennale published a statement in response, saying: “We do not deny our accountability. We humbly ask you to please grant us your attention for our response to the crucial questions of showing wounds and repair, to make sure our curatorial intentions and the aspirations of our exhibition are not misrepresented.”

These issues were bound to open some more wounds, yet to Attia, the idea is similar to the principle found in the work of German artist, teacher and art theorist Joseph Beuys, who created the piece “Show Your Wound” (1977). Beuys believed that art had to disturb. “Show it!” he insisted. “Show the wound that we have inflicted upon ourselves during the course of our development; the only way to progress and become aware of it is to show it.”

Not everybody agrees on the correct way to do so, but Berlin seems to be the right place to have this conversation in 2022, and despite the criticism, Attia intends to carry on showing the wounds.