![]()

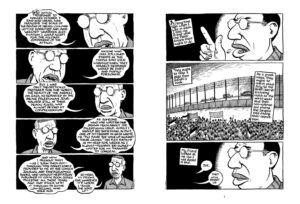

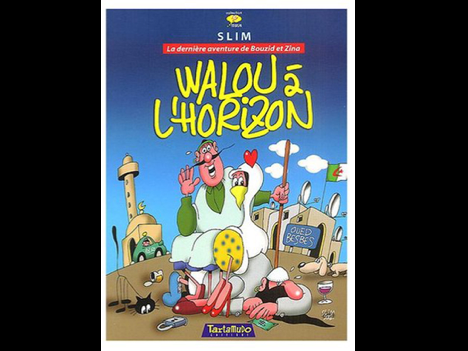

For International Press Freedom Day, Slim asked, “Does liberty have a sharp accent?” “Yes, as in throat slit.” “As in eliminated.” “As in imprisoned.” “As in mutilated.” “As in kidnapped.” “As in disgusted.”

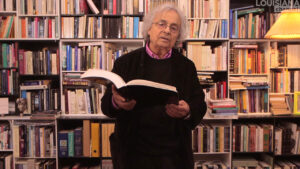

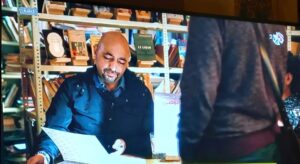

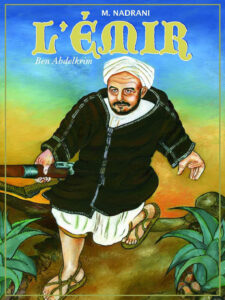

Slim (pen name of Menouar Merabtene)

Translated from the French by Susan Slyomovics

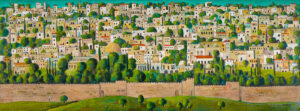

I was born in Sidi Ali Benyoub in 1945. Algeria had by then been under French colonial rule for 115 years, since 1830.

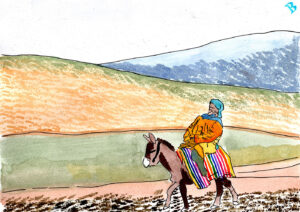

I have been drawing for a long time. I discovered that this was my real passion because let’s say, I had no other means to pass the time other than imagination and the pencil to concretize the imagination. I realized that I could make objects that I could not see. I could sketch landscapes that I did not see in front of me; for example, I could draw the Eiffel Tower and I was happy to see the Eiffel Tower on paper. So it started like that.

Drawing is very useful for people like me who grew up in a situation of social misery where there was not much available, apart from the dream in front of the windows of European settler stores of colonial French Algeria, which sold miniature cars or toys, especially during the Christmas holidays. It was extraordinary to come home to drawing. The difficulty was that it was necessary to have pencils, which were not very expensive. I also needed some paper. It was easy to obtain a kind of dull paper which was used to wrap sugar in the stores, a poor quality gray wrap that must have been made from waste. So I drew on it in black, which looked good on gray.

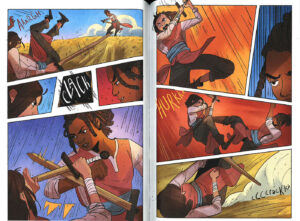

When I was five, we moved from our village to the nearby city of Sidi-Bel-Abbès, a colonial French city created as the headquarters of the French Foreign Legion. We lived in the district called El Graba, a “ghetto” for the “natives” (indigènes) or what the French called village nègre (“Negrotown”). I was one of four or five Algerian Muslims out of a class of forty boys admitted to the high school, the colonial college Lycée Laperrine (renamed at independence after Abdelkader Azza). I drew in my notebooks, especially towards the end of the school year when we could keep a lot of them at home. They had many blank sheets that I filled in with my pencil little by little. I started to sketch so well that a lot of classmates realized not only was I drawing but also writing texts to support the images. I made speech balloons to talk about the characters around me, especially in high school. I started to realize that I could draw my teachers and classmates also with speech balloons to make them speak. I exploited this possibility to make fun of some teachers a bit and share my mockery with the whole class since my drawings went all around the class without being seen, passed hand to hand under the desks. The teachers saw nothing but the whole class laughed in silence or smiled.

My most important passion after drawing was discovering the radio. At one time, we had a small radio that could pick up distant stations. I remember one that broadcast in French and Arabic from Tangier, Morocco. Evenings we listened with my mother to the news and I thought it was wonderful to hear people who spoke from afar, yet practically with us in the room. It was wonderful because it connected somewhat the phenomenon of drawing, text and sound all at the same time.

Next came my passion for movies when I started going to the Cinema Alhambra in El Graba owned by an Algerian man called Fasla who screened Egyptian films and newsreels with Gamal Abdel Nasser (and once a week there was special women’s viewing). Or I would go to the Cinema Olympia in town with a neighbor who let me in as long as I sat in the aisles or my uncles took me. I discovered a powerful extraordinary medium which had everything: images, movement while meeting up with people at the same time who gathered in the same place to look at the same white rectangle with images that moved and spoke with the sounds of music. It was a totality, I loved it. I really liked westerns whenever I had the rare opportunity to watch one. It was also fantastic that sometimes the high school placed a kind of projector in a room and we were shown films. So my passion is cinema, drawing, speech balloon texts, the imagination.

I told myself that in movies someone imagined the story. So I too will try to imagine a story and recount it. I began taking stock at one point of the future just at the time of Algeria’s independence from France in 1962. I was already 16½, 17 then and I told myself I absolutely must do this. Even if I don’t know if it’s possible, I had to find a school either to make films or learn graphic design, but an art school. Coincidentally this happened in 1963: my father had been released from Orléansville Prison (1957-1962) after spending seven years incarcerated by the French during the Algerian War of Independence for political reasons as a member of the National Liberation Front (FLN). He read the newspaper and showed me that a school, Institut de Cinéma et Télévision, had been created to train filmmakers that was staffed by Polish educators.

I was amazed, I wanted to go to Algiers.

Finally they bought me a train ticket. I took the entrance exam which specialized in my interests and I was accepted. I discovered a thousand things at once including that I was not the only dreamer. There were plenty of dreamers who came from all over Algeria, even France, and we shared this same passion. Each one chose what to study. I chose to be a camera operator, a cinematographer of images, while other friends chose scriptwriting, staging, lighting, editing, etc., so it worked out. We started making short films with silent cameras, no sound. We were telling stories as if in Charlie Chaplin’s time with only images and movement.

Unfortunately, the cinema school suddenly closed, to this day I still do not know the reason. Immediately afterwards, most of my colleagues, some 60 of us, were sent abroad with scholarships especially to the then-Eastern bloc socialist countries. I was sent to Poland for a practical internship at the television in Warsaw and worked with film director, Andrzej Kaminski. For animation, he sent me to the town of Bielsko-Blawa, where I found myself in a large cartoon studio. They took us to visit to Auschwitz, which was nearby. There I met fantastic artists, for example, my teacher, Władysław Nehrebecki (1923-1978), a brilliant filmmaker of animated cartoons. He taught me how to animate and draw and under his supervision. I made progress and completed a few good projects. But I wanted to go back home to Algeria at all costs to accomplish something. In Poland, they offered me work in an animation and drawing studio with a good salary. But the pull of my country was too strong. Poland was gorgeous, lovely landscapes, wonderful and beautiful men and women, but their winters were cold and hard.

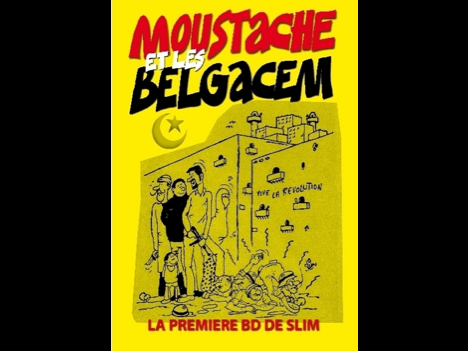

I found myself in Algeria with my training as a cartoon animator in April 1967 and finally I realized that here was nothing. Even in Europe, there was no cartoon studio except in Belgium. If there were none in France, then Algeria was worse, nothing at all. I said to myself that the only solution was comics. I found some friends from the time when we were in film school who were also comic book lovers. I remember Maz from El Watan journal, Aram the director of the center for animation, the cartoonist Sid Ali Melouah (1949-2007). We met and said to ourselves, why don’t we launch an Algerian comic book newspaper? We can make Algerian “Tarzans” and Algerian cowboys.

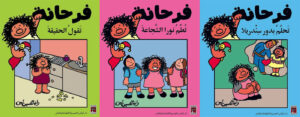

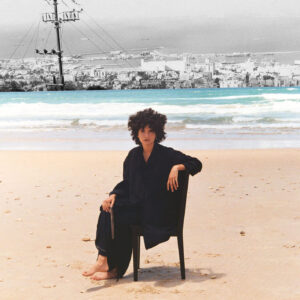

As we started to draw and make stories, we met wonderful people like Henrique Abranches (1932-2004), a Portuguese political refugee who came to Algeria to work, an anthropologist and revolutionary militant who wanted to liberate Angola. At the same time, he was a great cartoonist and he joined our group organizing nude male drawing workshops. He created a large woman called Richa (Arabic for “feather”). Later he went to Angola, acquired Angolan citizenship and became a cultural ambassador. We stayed in touch. In 1969, we started a small comic book newspaper. Already in 1964, I had created an Algerian woman cartoon character named Zina after I discovered the elegant women of Algiers different from the women of Sidi-Bel-Abbes, who wore the haik, a white flowing garment and veil that covered the face except for one eye. The Algerian national publishing house was a state monopoly and we could not publish whatever we wanted, for example, not Zina.

We also met someone wonderful who told us, give me your drawings, we will edit them, and he had them printed as a monthly magazine called M’quidech that ran from 1968/9 to 1974. It was a name without any meaning like Tintin. Printed in Spain, it had a huge success in Algeria that lasted a few years.

Then everything fell apart. We could not continue due to problems of management and underdevelopment. The adventure ended thereby allowing foreign comic books to be imported and sell well. In Algeria, there were practically no Algerian comic books, only imported ones for a while. Then the journal El Moudjahed (which had been founded in 1954 as the clandestine information newsletter of the FLN during the Algerian War) gave me their last page for cartoons. In 1969, my first page for them appeared at the same time as the Pan-African Festival of Algiers.

So I began … [to be continued]

Translator Susan Slyomovics is Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at UCLA and writes about visual anthropology in the Middle East and North Africa.