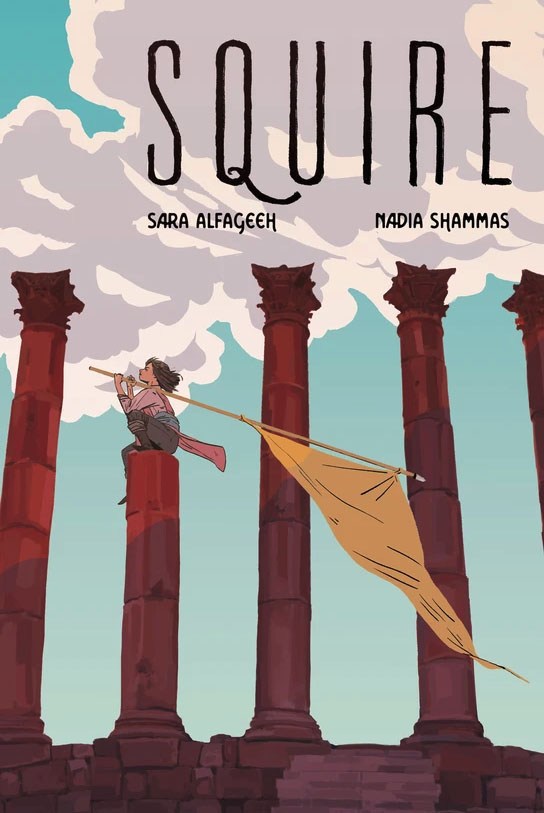

Squire, a graphic novel by Sarah Alfageeh and Nadia Shammas

Harper Collins 2022

ISBN 9780062945846

Katie Logan

It’s rare that a dedications page provides as much insight into the project before you as that of Squire does. Writer Nadia Shammas dedicates the 2022 graphic novel “to Edward Said, for giving me the language to see myself clearly.” Illustrator Sara Alfageeh’s dedication reads, “To ten-year-old Sara and long summers in Jordan.”

Somewhere between the complex, impassioned theory of a postcolonial and cultural studies icon and the childlike sense of adventure reserved for the longest summer days lies Squire, a text equally indebted to both. Ostensibly a young adult graphic novel with roots in fantasy and adventure, Squire is a familiar coming-of-age story elevated by deep thinking about the nature of history, empire, and narrative.

Squire’s plot initially follows a well-worn trajectory: Aiza, a poor girl from a remote village, is desperate to prove herself and rise above her station. She loves her family but leaves them behind when an opportunity to join an elite team of fighters presents itself, albeit in a way that forces her to hide crucial facts about her identity.

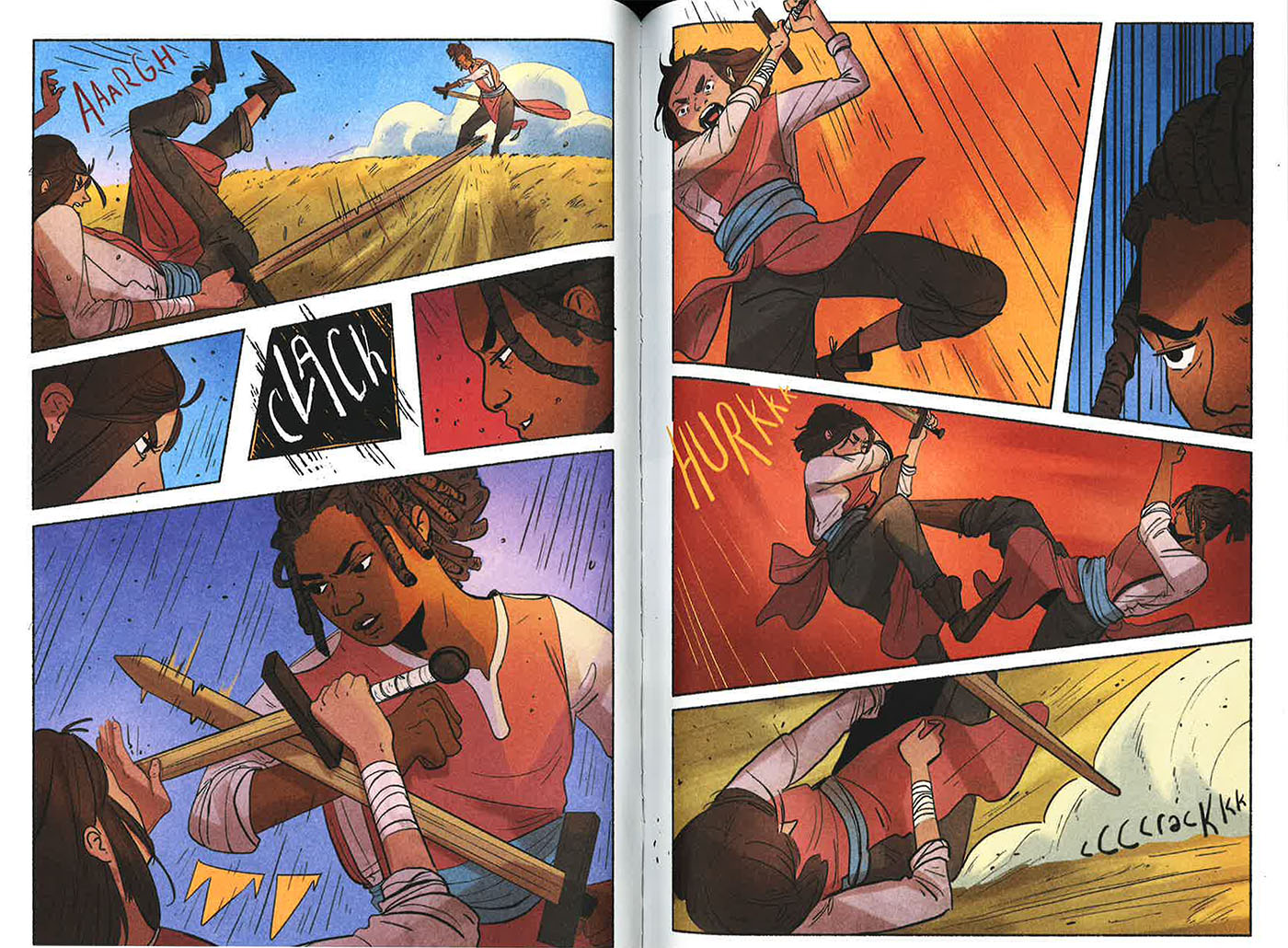

At training, Aiza learns that she’s out of her depth: she’s too small, too green, and too uninformed about the world. After a serious failure, she locates a reluctant yet soft-hearted mentor and commits to intensive 24-hour intensive training in secret. Her progress stuns her compatriots, and she rises to the top of her class just as threats both internal and external begin to confront this group.

Where Squire shines is not in the novelty of its plot but in the way it uses tropes like the martial training narrative and the underdog to offer a nuanced assessment of geopolitics. The predictability of several early plot points is simply a foundation for the places where Squire departs from other YA heroes’ journeys. In her writer’s bio, Shammas elaborates on her goal of “decolonizing genre tropes.” The protagonist, Aiza, isn’t an underdog simply because of her class, size, or gender: she’s Ornu, part of a group who seem to be an indigenous population conquered by the Bayt-Sajji Empire. While Aiza meets other characters from similarly conquered groups, it’s clear that the Ornu are particularly scapegoated, stereotyped as lazy and greedy, and made the butt of jokes. Bayt-Sajji dangles offers of citizenship — which includes unrestricted mobility and employment possibilities — to successful military recruits.

These promises, in addition to her own inherent restlessness, motivate Aiza to join. Her parents agree on the condition that she keep her Ornu identity secret. Of course, Aiza eventually reveals this identity, leading to a plot twist that meditates on empire’s insidious assimilation of outsider identity in the service of maintaining and building power.

Recommended Reading

Aomar Boum, “Why COMIX? An Emerging Medium of Writing the Middle East and North Africa”

Katie Logan, “The Politics of Wishful Thinking: Deena Mohammed’s Shubeik Lubeik”

George Jad Khoury, “Rebellion Resurrected: The Will of Youth Against History”

Jenine Abboushi, “Sudden Journeys: Deluge at Wadi Feynan”

Aiza’s coming-of-age narrative is not simply about self-discovery; crucially, her journey allows her to recognize that self in the context of the political and cultural forces around her. As she comes to know her cohort of cadets — the fashion-forward Husni from a colonized island nation; Sahar, another female recruit whose family depends on her success; and Basem, desperate to win his senator father’s approval — she witnesses the ways each fits into the narrative of empire. General Hende, who leads the recruits’ training, explains, “Merit and skill are good in war. To win a war, however, you need more than skill. You need an idea, an ideology. History is that, and more. History is the story you tell about yourself.”

As these recruits train, Shammas and Alfageeh demonstrate the ways conquered peoples are reinscribed into this history: they take tests at which they fail if they don’t parrot back the empire’s approved narrative about conquest. They learn and exchange jokes about populations like the Ornu, reinforcing social standing through humor. And when they fail to meet the standards set by the empire, they are sent to the front lines as cannon fodder, a chilling reminder of Bayt-Sajji’s necropolitics.

Aiza’s survival depends on her ability to name and challenge the colonial logics shaping her life and those of her friends. Promoting Aiza to squire in an effort to demonstrate Ornu loyalty to Bayt-Sajji, General Hende calls her “a wonderful story.” As a character, Aiza’s growth comes not from building her strength or even embracing her individual Ornu identity. Instead, it comes from her rejection of the “story,” and specifically from sacrificing her aspiration to be the singular hero turned legend.

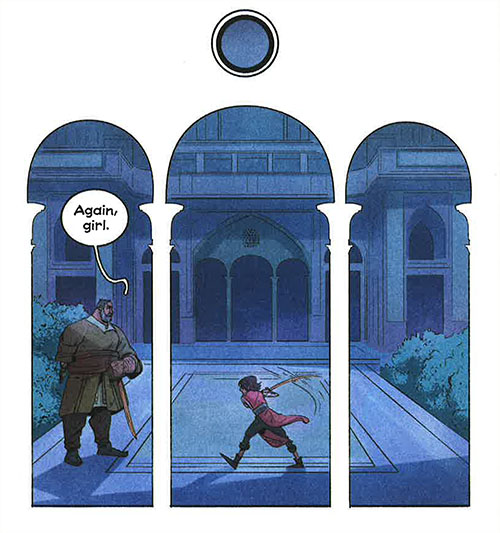

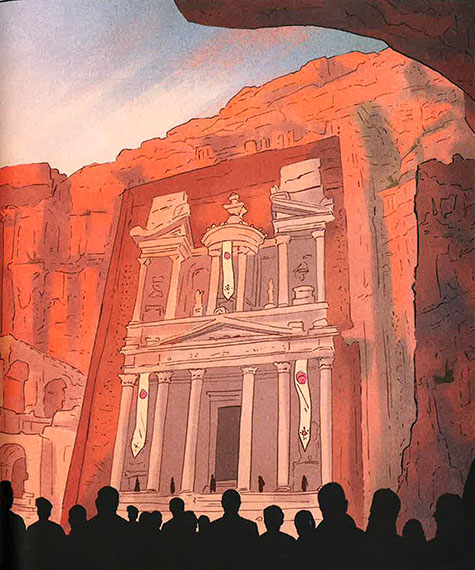

Aiza’s journey toward recognizing the mechanics of conquest and narrative politics is dependent on Alfageeh’s stunning visuals, which advance an architecture of empire. Rather than the “classic” nine-panel grid made famous by comics like Watchmen, Alfageeh’s panels frequently morph into the shape of Islamic architecture, shapes that meticulously represent Squire’s setting while reminding viewers of the way arts and architecture reinforce an occupying power’s identity. In an insightful nod to Alfageeh’s Jordanian heritage, most of the recruits’ training takes place at a Bayt-Sajji base clearly modeled on al-Khazneh, the Treasury of Petra. Petra’s famous pink sandstone also echoes throughout the dreamy pinks and reds coloring the comic.

Jordan has been conscripted to “play” any number of Middle Eastern settings on screen. Due in large part to former Queen Noor’s efforts to host Hollywood filmmakers such as Steven Spielberg, unsafe filming conditions in neighboring countries, and an increasingly talented and experienced local pool of film crews, Jordan has appeared as the Hatay Province (Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, 1989); Iraq (The Hurt Locker, 2008, and Zero Dark Thirty, 2012); and Iran (Rosewater, 2014, and Holy Spider, 2022), among others. By participating in this tradition of “costuming” Jordan, and particularly an ancient site like Petra, to depict the Bayt-Sajji empire, Alfageeh’s images actually challenge the representational logic of these previous efforts. Her images are an homage to these places and those childhood summers, one that suggests an overlap of colonial histories rather than displacing one for another. Referencing Petra in the context of a project explicitly concerned with the politics of place and narrative throws into relief the Orientalizing impulses governing these other projects, which construct stories about the Middle East in a way that presumes easy erasure of one place and history to serve another.

Strangely enough, then, a text such as Squire, which is explicit about its fictitious and fantastical origins (from the beginning we know we’re in an alternate reality as the empires and populations it names are made up, although the mechanisms are rooted in realism), is best able to see and represent the complex histories and narrative structures that continue to shape a place such as Jordan. Shammas muses in an afterword that:

In many ways, fantasy and history walk hand in hand, but there’s an important thing about the way we view history in comparison: history, is above all else, neutral. If you are on the outskirts of the empire’s convenient history, however, you know it’s anything but… [H]istory, altogether, is a tool, and tools are neutral until they’re wielded.

In Squire, Shammas and Alfageeh have created an effective tool in their own right, one that empowers their younger readers to question the narrative structures and power dynamics through which their own families, histories, and homes are defined.