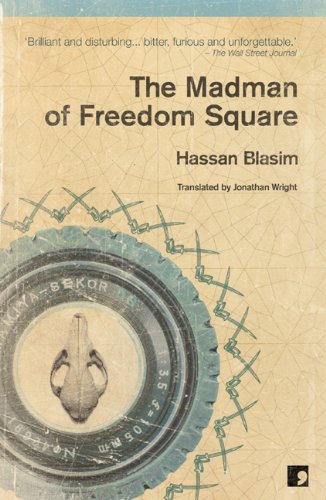

Reminiscent of Ghassan Kanafani’s novella Men in the Sun, this bleak and hyper real short story by Hassan Blasim is included in his prize-winning collection, The Madman of Freedom Square, and appears here by special arrangement with his publisher, Comma Press. These stories present an uncompromising view of the West’s relationship with Iraq, spanning over twenty years and taking in everything from the Iran-Iraq War through to the Occupation, as well as offering a haunting critique of the post-war refugee experience. Blending allegory with historical realism, and subverting readers’ expectations in an unflinching comedy of the macabre, Blasim manages to convey both the phantasmagoric and shockingly real. He often writes with a light touch despite the fact that his stories are steeped in personal nightmare.

Hassan Blasim

This story took place in darkness and if I were destined to write it again, I would record only the cries of terror which rang out at the time and the other mysterious noises that accompanied the massacre. A major part of the story would make a good experimental radio piece. For sure most readers would see the story as merely a fabrication by the author or maybe as a modest allegory for horror. But I see no need to swear an oath in order for you to believe in the strangeness of this world. What I need to do is write this story, like a shit stain on a nightshirt, or perhaps a stain in the form of a wild flower.

In the summer of 2000 I was working in a bar in the middle of Istanbul. My broken English helped me in the job, since the customers were tourists, mostly Germans who also spoke laughable English. At the time I was on the run from the hell of the years of economic sanctions, not out of fear of hunger or of Saddam Hussein. In fact I was on the run from myself and from other monsters. In those cruel years fear of the unknown helped obliterate the sense of belonging to a familiar reality and brought to the surface a savagery which had been buried beneath a man’s simple daily needs. In those years a vile and bestial cruelty prevailed, driven by fear of dying from starvation. I felt I was in danger of turning into a rat.

I saved some money from my work and paid it to those who smuggle the human cattle of the East to the farms of the West. There were ways of smuggling that differed in price: traveling by air on a forged passport, which was very costly, and walking with the smuggler through forests and rivers on the borders, which was the cheapest way. There was the sea route and the truck route, which I had considered, though I was disturbed by stories of the device the police use to measure the level of carbon dioxide in the trucks to detect the breath of those hiding inside them. But it was not that device which made me abandon the idea of traveling by truck, but rather the story of Ali the Afghan and the massacre on the truck to Berlin. The Afghan was a treasure trove of smuggling stories. He had lived in Istanbul illegally for ten years. He worked in forgery and selling drugs, to spend what he earned on Russian prostitutes and bribing the police. Some people have ridiculed me for believing the story of the truck to Berlin. In fact I have more than one reason for believing such stories. Because in my view the world is very fragile, frightening and inhumane. All it needs is a little shake for its hideous nature and its primeval fangs to emerge. Obviously you already know many similarly tragic stories of migration and its horrors from the media, which have focused first and foremost on migrants drowning. My view is that as far as the public is concerned such mass drownings are an enjoyable film scene, like a new Titanic. The media do not, for example, carry reports of black comedy, just as you do not read stories about what the armies of European democracies do when at night, in a vast forest, they catch a group of terrified humans, drenched in rain, hungry and cold. I have seen how the Bulgarian police beat a young Pakistani with a spade until he lost consciousness. Then in the bitterest cold they asked us all to get into a river that was almost frozen over. That was before they handed us over to the Turkish army.

Ali the Afghan says that there were thirty-five young Iraqis, dreaming youngsters who had made a deal with a Turkish smuggler to carry them in a closed truck exporting tinned fruit from Istanbul to Berlin. The deal was this: Everyone would pay $4,000 for a trip that would last just seven days; the truck would travel by night and spend the day stopped at small border towns; anyone who wanted to take a shit would have to do that during the daytime; pissing would be allowed during the night in empty water bottles; no one could carry a mobile phone during the trip; everyone must keep silent and breathe quietly while the truck was stopped at border posts or traffic controls, and there should be absolutely no quarreling. But what worried the Berlin truck group was the story published in the Turkish newspapers a few days earlier about a group of Afghans who paid an Iranian smuggler large sums of money to carry them by truck to Greece. The truck drove for a full night. At daybreak it stopped and the smuggler told them to get out quietly because they had reached a Greek border town. The Afghans got out of the truck hugging their bags, feeling a mixture of joy and fear, and sat down under a giant tree. The smuggler said they were in a small Greek wood and all they had to do was wait till the morning and, when the Greek police turned up, they should immediately apply for asylum. In the morning the newspapers published a picture of the Afghans sitting in a public garden in the middle of Istanbul. The truck had driven them around the streets of Istanbul all night and had not even left the suburbs. As in all stories of fraud and deception, the Iranian and his truck vanished and the Afghans were thrown in jail pending deportation.

But the Berlin truck group had no choice but to take the risk. To be frightened of stories of fraud would mean paralysis, losing hope and going back to a country where hunger and injustice were rife. They also relied on the reputation of the famous smuggler, who they were told was the best and most honest smuggler in all Turkey. So far he had never failed and had not tricked anyone. He was a pious man and had performed the haj pilgrimage three times, and so was called Haj Ibrahim.

Haj Ibrahim’s truck left Istanbul by night, after the “customers” had loaded up with food and bottles of water. The dark and heat inside the truck was intense, though air did leak inside through small invisible holes. For fear that the air would run out, the young men were breathing rapidly, like someone preparing to dive into a river. After five hours of travel, the smell of bodies, sweaty socks and the spicy food they were eating in the darkness made it even stuffier. But the first night was a success. In the morning the truck stopped at a garage in a border village. The back door was opened and the customers could breathe again, their hopes renewed. The garage was a former cowshed and two young men supervised the shitting operation. The travelers were not allowed to get off the truck, let alone go into the village or anywhere else. One of the two young men took them in turn to a small and very dirty toilet in the corner of the cowshed, while the other bought food and water for them and came back at the end of the day.

On the second night there was a Mercedes car which drove well ahead of the Berlin truck to check the road and provide the truck driver with information. The Berlin truck drove in peace all the second night, making only three very short stops. In the morning they took them this time to a large garage which had other trucks and it was easy to hear the noise of the town.

On the third night a military jeep drove ahead of the truck to secure the route. In this stage of the trip the truck drove only five hours, before it suddenly stopped, turned and retraced its path at high speed. In the darkness of the truck the young men were discouraged and could feel the driver’s panic in the crazy way he was driving. They started to grumble and some of them recited prayers and verses of the Quran to themselves or under their breath. One young man kept repeating the “Throne Verse of the Quran” out loud. He had a beautiful voice, but it was marred by his plaintive tone, which added to the dismay of the other travelers. The truck drove at this speed for close to an hour, then stopped again. A quarter of an hour later the journey resumed at a moderate speed, but the young men could not make out which direction they were moving in: Some favored the idea that they were going back, others believed they were continuing the journey. They thought it was the smuggling mafias that were giving instructions to the driver by mobile phone, depending on the road conditions and dangers such as police patrols. Then the passengers felt that the truck had started to drive along a winding dirt road. The truck suddenly came to a halt, the driver turned off the engine and an eerie and mysterious silence reigned inside the truck to Berlin, a satanic silence that would bring forth a miracle and a story hard to believe.

The thirty-five young men waited in the darkness of the truck more than three hours, whispering to each other about what had happened. Some of them tried to peek out of the very small holes near the back door. Their watches showed 7:10 in the morning, time to stock up on water. They still had enough food but the water would run out quickly, and then there was the need to take a shit. That’s how the unrest began. Some of them started to kick the sides of the truck and shout out to anyone outside. Three of them objected and asked the others to keep quiet. The smell of strife hung in the meager and electric air. They could see each other only as dark shadows and could tell each other apart only by judging the direction of someone’s voice. By midday almost everyone was banging on the walls and back door of the truck and calling out for help. Some shat in food bags, and the repulsive smell built up inside the truck like strata of rock. The young men’s breathing, taken together, was like that of a monster roaring in the dark. The fear and the smell so shattered everyone’s nerves that quarreling and fistfights broke out in the gloom. The fighting spread, then after an hour died down because thirst had restored the calm. Everyone sat around whispering and speculating in low voices, like a hive of bees. Every now and then one of them would curse or kick the walls of the truck. At this stage most of the young men were making sure they had hidden in their bags what food and water they had left.

Despite the pitch black, which made it impossible to tell a face from a foot, some of them did things which were not really necessary under the circumstances. One would tie up his shoelaces, another would take off his watch and hide it in his pocket, and a third would change his shirt in the dark. Such is the imagination of man, which is strangely active in situations such as this, and acts like an alarm bell or a hallucinogenic drug.

On the third day there was complete chaos. Some young men who still had the energy to hang on to life tried to break down the truck door, while others kept shouting and banging on the walls. One of them was begging and pleading for a gulp of water. The sound of farts and insults. Quranic verses and prayers recited in loud voices. Some were overcome with despair and sat thinking about their lives like patients about to die. The smells were unbearable, enough to exterminate more than one flock of the birds hovering over their heads. I am not writing now about those sounds and smells which come and go along the paths of secret migration, but about that resounding scream which suddenly burst from the chaos. It sounded like an unknown force which transformed the uproar and chaos of the truck into a cruel layer of ice. Then there reigned an intense and cloying silence which made it possible to hear the heartbeat of every traveler. It was a scream that emerged from caves whose secrets have never been unraveled. When they heard the scream, they tried to imagine the source of this voice, neither human nor animal, which had rocked the darkness of the truck.

It seemed that the cruelty of man, the cruelty of animals and legendary monsters had condensed and together had started to play a hellish tune.

After four days the Serbian police came across the truck on the edge of a small border town surrounded by forest on all sides. The truck was in an abandoned poultry field. It’s not important now what happened to the smugglers, for all these stories are similar. Perhaps the smugglers found out that the police were watching their movements and wanted to hide a few days, or perhaps it was for some trivial reason connected with disputes between the smuggling mafias over money.

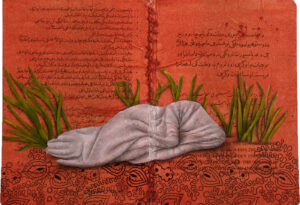

When the policemen opened the back door of the truck, a young man soaked in blood jumped down from inside and ran like a madman towards the forest. The police chased him but he disappeared into the vast forest. In the truck there were thirty-four bodies. They had not been torn apart with knives or any other weapon. Rather it was the claws and beaks of eagles, the teeth of crocodiles and other unknown instruments that had been at work on them. The truck was full of shit and piss and blood, livers ripped apart, eyes gouged out, intestines just as though hungry wolves had been there. Thirty-four young men had become a large soggy mass of flesh, blood and shit.

No one believed the story which Jankovic, the Serbian policeman told. In fact they made fun of him. Those who were with him there did not corroborate his account, though they did agree with him about the bloodstained youth who ran off into the forest. The Serbian newspapers asked why the youth disappeared but the police claimed that he crossed the border into Hungary.

In bed Jankovic looks at the ceiling and speaks to his wife: “I’m not mad, woman. I tell you for the thousandth time. As soon as the man reached the forest he started to run on all fours, then turned into a grey wolf, before he vanished …”

The Truck to Berlin, translated from the Arabic by Jonathan Wright, first appeared in The Madman of Freedom Square, published by Comma Press.