On the day Kabul fell to the Taliban, 5,000 inmates living in communal pens in Afghan’s main military prison, built by the US during George W. Bush’s administration, walked free.

Andrew Quilty

Sunday, August 15, 2021, was yard day for Hejratullah and Fawad. Every second day, they and their cellmates in the Parwan Detention Facility, which was encircled by Bagram Airfield, were given time in a cage-in pen accessed directly from the backs of the cells, where they would eat their breakfast of bread and green tea on the concrete in the sun. On this day, the inmates sitting in the sun were even more buoyant than usual, singing anthems as they slurped their tea. Word had arrived that freedom was near.

Around 30 inmates shared each of the dozen cells into each prison block. Hejratullah’s and Fawad’s cells were around ten meters long and six meters wide. The inmates slept shoulder to shoulder on thin mattresses, with their toes pointing toward the center of the room. They made space by bundling in scarves all their belongings — including handmade boxing gloves, and sneakers made from the remnants of prison garb — and hanging them from torn lengths of fabric tied to the cage ceiling; the web of fabric strips also allowed scarves and shawls to be draped between the mattresses for privacy. Piles of religious texts were stacked in the corners. Some prisoners collected date seeds in a jar, then shaved the sides until they were smooth, drilled narrow holes into them, threaded them onto twine and tied them into loops of Islamic prayer beads. Toothbrushes and disposable razors sat in juice boxes that had been cut in half and bonded to the wall with thick layers of toothpaste …

Prisoners smuggled Nokia phones inside the detention center by bribing guards, then sold them for as much as 60,000 Afghani (approximately US $750 at the time). In Hejratullah’s cell, in the corner furthest from its heavy sliding door, two hanging blankets created a cubicle large enough for a single person to stand within. It was from this makeshift phone booth, where calls were limited to a maximum of two minutes, that news arrived from the outside world and was then passed around the prison. And by 10 a.m. on August 15, some momentous news had been received after a succession of calls: Charikar, the district center of Parwan province, and only 20 minutes by road from the prison, had fallen into Taliban hands. Soon after, a guard who worked as an informant for the Taliban came to the cell and informed the prisoners that Pul-i Charkhi Prison in Kabul has been taken over by the Taliban and all the prisoners had been released. “You’re going to be released soon too,” said the guard.

Fawad and his cellmates, who were in another block, weren’t given the same courtesy. When a guard ordered the prisoners into their cell before their allotted time, the cell leader protested, drawing senior prison officers who threaten to send in the riot squad if the inmates didn’t comply. When the prisoners heard gunshots in the distance, they halted their protest, worried that the guards might use the moment of tumult to shoot them and then claim they were killed in combat. The cell leader suggested everyone recite from the Koran. “Today we might be martyred,” he told them.

Before long, the prison guards in both Hejratullah and Fawad’s cellblocks had disappeared altogether. Not long after that, shouts could be heard echoing through the concrete buildings — sounds of disorder, confusion, elation. Men in prison uniforms started appearing in the corridors to open the cells’ sliding doors and urge the prisoners to get out. “No one’s here,” they said. “No soldiers, no commanders. The mujahedin are here and they’ve come to release us.”

Hejratullah and his cellmates were still locked in the caged outdoor area, but they managed to climb above the access door and through a window that the inmates had always resented because of the sun that poured through in the mornings and the cold drafts that blew in during winter. When they dropped down into their cell, the door was open and the guards were nowhere to be seen.

Fawad and the inmates in his block were more wary. Two months earlier, there had been an attempted breakout … [W]hen the prison guards realized what was happening, they responded with overwhelming force … Scores were injured … “So when they told us to leave this day,” says Saeed Rahim, one of those who shared Fawad’s cell, “we remember the incident that happened a couple of months ago.”

However, once the sounds of footsteps and voices within the block had faded and been replaced by the more distant noise of larger numbers of men, Fawad and his cellmates left as well, walking out through the area where ordinarily they would be shackled and blindfolded before attending court or meetings with their defense lawyers. “The treatment of mujahedin,” says Hejratullah, “wasn’t very good. They could do whatever they liked with us.”

The only doors the inmates couldn’t open were the dead bolted main entrances to the cellblocks, which from the outside looked like industrial warehouses. But the escapees pried away just enough of the iron sheeting that lay where the walls met the doorframes to allow them to crawl through. Once out, they would help liberate those in the other blocks.

Senior Taliban inmates maintain mobile phone contact with commanders outside the airfield, who reminded them to be patient, throughout the escape. “We were told not to leave the prison until 2 p.m.,” says Hejratullah. There were hundreds of prominent Taliban commanders and functionaries inside the prison, and the group’s military commission wanted to ensure the facility was properly secured before the inmates rushed for the front gates. But for the first prisoners to break free from the cellblocks, many of whom had been imprisoned there for more than a decade, the impulse to continue towards the perimeter of the airfield was too strong. Around midday, a large group of prisoners pulled away a strip of cyclone fencing from one side of the tin-roofed walkway that connected the cellblocks, and they ran for freedom. Many of them were obliterated by a strike from one of the Afghan Air Force’s attack aircraft which had been prowling the skies above. Even then, inmates continue to squeeze through the holes in the outer shells of the cellblocks to fill the covered walkway, while the scattered figures and body parts of those hit by the airstrike remained where they had fallen: A warning for any who wanted to push further into Bagram Airfield.

With the aircraft still circling, the prisoners at first hid under the walkway’s tin roof. Around 1 p.m., they lined up in five rows, more than 100 men in each, faced Mecca and prayed. “The happiness on the prisoners’ faces was a happiness that couldn’t come from anything else,” says Hejratullah. By the designated time of 2 p.m., they began running, looking for a way out. Of course, none of the prisoners were familiar with the sprawling airfield outside their cellblocks, which was divided by endless rows of demountable concrete blast walls that obscured the horizon at every turn. The inmates who headed east came to its perimeter after a few hundred kilometers, but those who fled west ventured nearly five kilometers before they even reached the airfield’s dual runway, let alone the perimeter wall beyond it.

“Bagram is a big place,” says Hejratullah. “But I only ever saw the inside of my cell. When they took us out they put blacked-out goggles on us.”

As the escapees dispersed into smaller groups, those who commandeered abandoned military vehicles became the most obvious targets from the air. Others looted an ANA [Afghan National Army] armory and absconded with American-made weapons. Once the inmates reached the outer wall, says Saeed Rahim, “some would go south and others would go north, looking for a gate.”

As Hejratullah and four friends from Chak District, Maidan Wardak province, stopped at an exit on the airfield’s north-eastern side, contemplating which way to turn when they reached the road, a bomb fell from the sky to strike a nearby group of men, killing several of them. Hejratullah says that he saw “80, 90, 100” inmates killed by airstrikes while trying to escape.

In response to questions regarding American airstrikes in Afghanistan on August 15, a US Central command spokesman denied US aircraft had conducted strikes in Bagram: “Coalition forces,” the spokesman said, “conducted one airstrike in Kandahar province on 15 Aug.” Lieutenant-general Haibatullah Alizai, on the other hand, would tell me he ordered the Afghan Air Force to unleash all is firepower that day, and that strikes were conducted in and around the prison and Bagram Airfield.

Hejratullah and his friends, all of whom had by now changed out of their prison garb, walked out the gate carrying M-16 rifles taken from the ANA armory and turned into a road that encircle the eastern half of the airfield. They walked for an hour until they reached the turn-off to the new Kabul-Bagram Road.

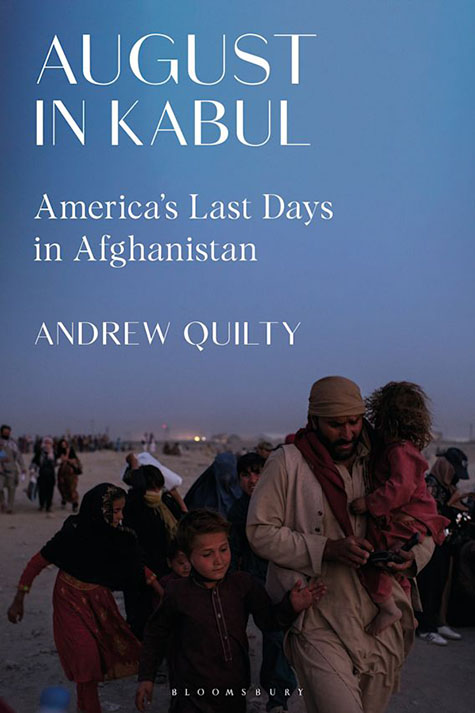

This is an edited extract from Andrew Quilty’s book August in Kabul: America’s Last days in Afghanistan, which was published by Bloomsbury Academic earlier this year.